As kids, most of us try holding our breath underwater. We swim submerged laps in backyard swimming pools or dare each other to touch the sea floor at the beach. Turns out we’re freediving, a sport that’s enjoying a seemingly stratospheric increase in popularity.

The term freediving refers to voluntarily submerging your face underwater on a single breath, an act also known as apnoea – the suspension of respiration. It may encompass a variety of activities such as spearfishing, underwater photography, or simply diving a bit deeper during snorkelling. But when it’s discussed as a specialised pursuit, it usually refers to people focusing on apnoea and trying to prolong their time underwater, in either a recreational or competitive arena.

Why spend more time underwater on a single breath? It’s partly to do with the sensory experience, says Dr Jody Fisher, an applied mathematician working on interdisciplinary areas, including the physiology of freediving.

“If you’re on a deep dive in very clear water, you’re surrounded by bright blue and you get these ribbons of light that are just streaming around,” says Jody, who’s also the technical officer of the Australian Freediving Association (AFA), the not-for-profit organisation that promotes freediving in Australia. “It’s incredibly beautiful and, on top of that, you’re holding your breath, so your heartbeat is slowed. You get a sense of being suspended in time. It’s just incredibly peaceful.”

It seems plenty of people agree. Jody says freediving schools are popping up across the country, and there’s been an exponential increase in people becoming certified freedivers and competing. Apart from the COVID pause in recording data in 2020, the sport has averaged 40–80 per cent growth annually since 2014.

For many, the path to freediving begins with scuba diving. Lisa Borg, AFA secretary, explains that many former scuba enthusiasts choose to ditch the bulky equipment, finding the interaction with marine wildlife is enhanced without scuba’s exhaled bubbles. Other freedivers were previously snorkellers or spearfishers who simply wished to stay underwater longer.

Lisa’s own entry into freediving followed a serious spinal-cord injury in 2008. “My doctors have said to me they don’t know why I’m walking,” she says. “I have a lot of pain and a lot of physical issues that I have to deal with.”

With many of her usual sports impossible after the injury, Lisa took a freediving course in Bali. On return to her home in South Australia, she joined her local pool-based freediving club. Before she knew it, the club’s community had encouraged her to compete in pool-based competitions and she found herself on the board of the AFA.

For Lisa, freediving and meditation have combined to help her cope with chronic pain. “What can happen is that the pain signals get ‘stuck on’, and freediving and meditation help turn it down,” she says. “It’s also the community; I love the fact that most people are really willing to support everybody else. You’ll go to a competition like World Championships or the Pan Pacifics and you’ll see athletes from other countries coaching each other.”

The community spirit is also strong in recreational freediving, where groups dive together in swimming pools, freshwater lakes or in the ocean. Lisa says there are a few particularly favoured places around Australia. In SA there’s Rapid Bay and a freshwater sinkhole near Mount Gambier. Other hotspots include Mornington in Victoria, and Queensland’s Lady Elliot Island, North Stradbroke and freshwater Lake Eacham. In New South Wales, Cabbage Tree Bay in Sydney is popular, while in Western Australia, it’s hard to go past Ningaloo Reef.

Competitive freediving in Australia is regulated by the AFA, which organises national competitions. The AFA sits under the umbrella of the Australian Underwater Federation, which is the governing body for all underwater sports in Australia. Internationally, two bodies run freediving competitions: the International Association for the Development of Apnea (AIDA) and the World Underwater Federation (CMAS). The AFA aligns with both bodies and adopts similar competition protocols.

Eight competitive disciplines are recognised by AFA and the two international bodies. Four are pool-based disciplines, with three “Dynamic” categories, where divers swim as far as they can in a 50m pool on a single breath. Their horizontal distance is recorded across three areas: Dynamic Monofin, using a monofin similar to a mermaid’s tail, which gives the greatest power; Dynamic Bifins, where fins are worn on each foot; and Dynamic No Fins. The fourth pool category is Static Apnea, where the diver floats without moving, face submerged, for as long as possible on a single breath.

Depth competitions are held in the ocean, deep lakes or sinkholes. Divers follow a vertical rope to a pre-announced depth, retrieving a tag before surfacing. Divers use a monofin in the Constant Weight category, while other categories include Constant Weight Bifins and Constant Weight No Fins. The final category is Free Immersion, where divers may pull themselves down the rope to their goal depth.

Safety is at the forefront of competitive freediving and dedicated safety divers stand by to help any competitor in trouble. Competitors must also complete a surface protocol before their dive is deemed legal. Within 15 seconds of finishing any dive, the diver must remove facial equipment such as goggles and nose clips and say the words, “I’m okay”. They must also make the okay signal with their thumb and forefinger making a circle and their mouth must remain above the water. These measures show the judges that the diver is fully conscious and functioning, and, most importantly, provide unequivocal incentive for divers to compete within their physical limits.

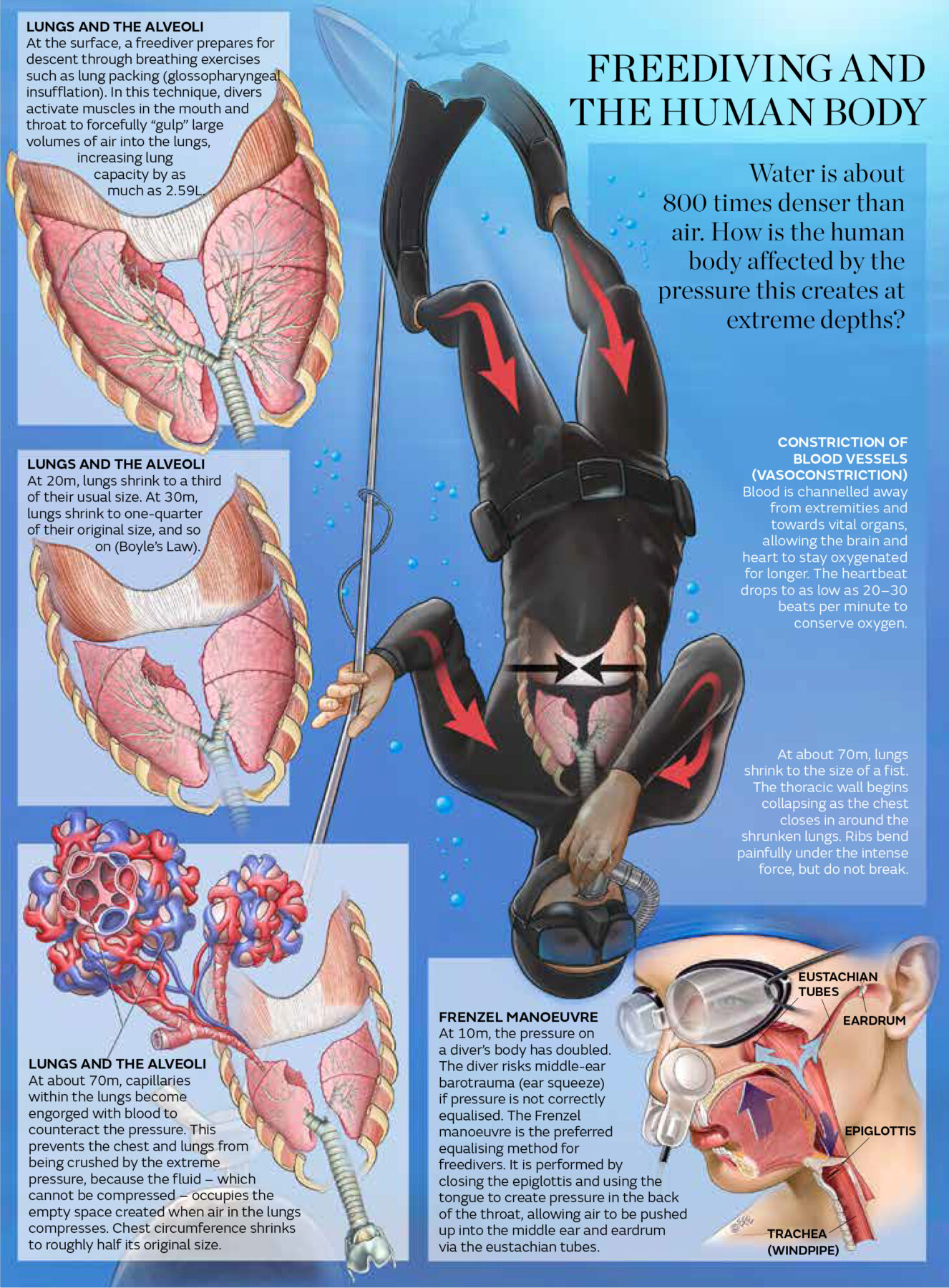

The human body has some remarkable physiological adaptations to help protect it during diving. What’s known as the mammalian dive response ensures our body instinctively recognises water as a low-oxygen environment. Jody explains that this suite of reflexes is all centred around conserving oxygen. “The first, most obvious reflex is [when] just putting your face in water, your heart rate should drop,” she says. “And it’s a stronger effect when it’s cold water. There’s a more pronounced effect for divers who’ve been training for many years; for elite freedivers, their heart rates will be dropping probably well below 30 beats a minute on deep dives.”

As divers descend deeper, the next reflex is peripheral vasoconstriction. In this response, blood moves from the arms and legs and is pumped towards the heart, brain and vital organs. The spleen also contracts, secreting more red blood cells into the circulatory system to assist with oxygen transport.

Extreme water pressure can cause the lungs to compress to the size of an orange. But the body has a way of preventing them from collapsing altogether. Jody explains that within our lungs are branching tubes that terminate in tiny air sacs, the alveoli, which are responsible for gas exchange. In a deep dive, these gas-filled spaces are compressed. To compensate, the blood vessels that are woven through this area expand with extra blood to physically support the lungs. During ascent the process reverses.

With all of these physiological responses occurring, it’s fair to wonder if this is a dangerous sport. But Jody insists that if divers follow the safety protocols, freediving is safer than many other sports. “If someone makes an error on a dive, and I stress it’s because someone’s made a mistake and may have overextended themselves, their oxygen levels might end up dropping far enough that they could lose consciousness,” Jody says. This is known as hypoxic blackout.

“But there’s still enough oxygen to the brain at this point. It’s actually yet another protective response, a way to conserve energy. As long as someone has a safety diver or buddy who’s looking after them, it should only last a couple of seconds and there shouldn’t be any kind of long-term problems.”

Jody says blackouts usually happen near the surface at the end of a dive when someone has pushed themselves too far. That’s why buddies must always dive in a “one up, one down” situation; one diving and one watching from the surface.

According to the AFA, in more than 100,000 dives internationally there has never been a death in a competition due to hypoxic blackout when basic safety protocols are followed. However, accidents can happen in any sport. In 2013 the sport suffered its first and only recorded competition fatality at the Vertical Blue freediving competition in The Bahamas. Nicholas Mevoli, an American competitor, died from pulmonary barotrauma (lung squeeze).

The former “No Limits” discipline previously saw divers reach a maximum depth in any way they possibly could. Divers usually attached themselves to weighted sleds for a speedy descent and inflated gas balloons to resurface. In 2012 Herbert Nitsch of Austria descended to the inky depths of 253m. Several minutes after surfacing, Nitsch was flown to hospital with severe decompression sickness, which resulted in several brain strokes and months of recovery. Following this and other incidents, that particular discipline was removed from competitions by AIDA in 2012. Jody explains that the sport now prioritises athletic performance rather than disciplines that are mechanically powered.

Kyra Andrijich is a freediving instructor and owner of a school on WA’s Ningaloo Reef. She draws a clear link between yoga, meditation and freediving, saying all rely on breath control and have a calming effect.

“Most people breathe quite shallow or just a small amount in the chest,” she says. “Whereas if you look at a baby, their belly is rising and falling. When we go back to that ‘belly breathing’, it triggers one of the biggest nerves that we have – the vagus nerve, which comes under the parasympathetic nervous system. That’s stimulating us to have a slower heart rate.”

According to Kyra, activating the parasympathetic nervous system not only helps with freediving, but also aids digestive function, lowers blood pressure and reduces stress.

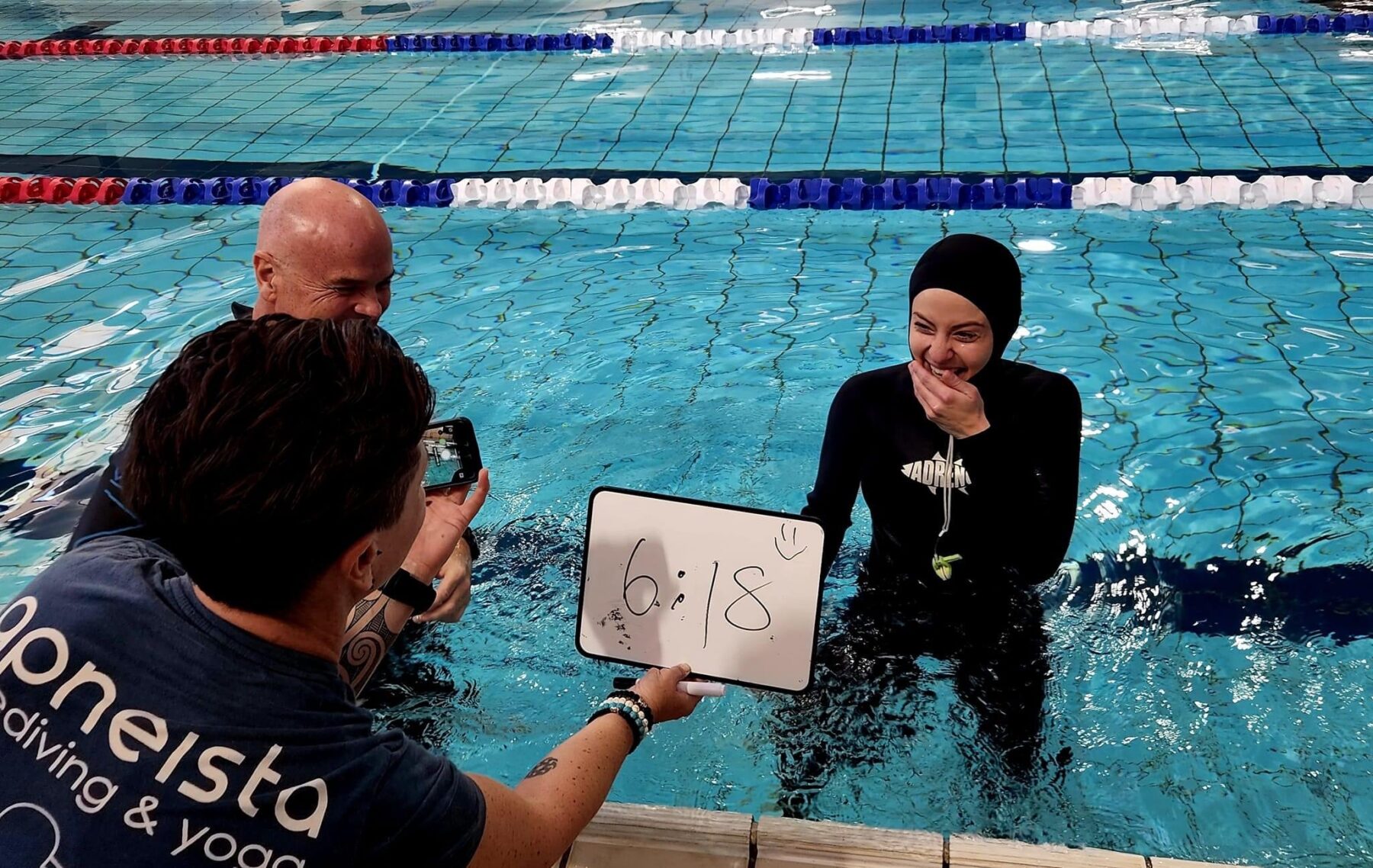

Also extolling the health positives of freediving is Jordan Duncan, who currently holds three of the four Australian pool freediving records for women. In the category of Dynamic Bifins, Jordan can swim 200m on a single breath, while in the Dynamic Monofin category she can knock out 209m. In July 2022, Jordan broke the record for Static Apnea by holding her breath for a staggering six minutes and 18 seconds. Despite her achievements, the start of Jordan’s freediving career was challenging.

“I’d struggled with an eating disorder for a really long time,” Jordan says. “My body wasn’t coping and I had a couple of blackouts in competition. I knew I couldn’t keep going the way I was; something had to give.” Since then, she’s taken serious steps to get her health back on track.

Jordan finds solace in the water. “Freediving has absolutely been my lifeline,” she says. “My mind is busy but I’ve learnt how to be a lot more present in that couple of minutes when I’m underwater, not thinking about what’s going on elsewhere in my life but just really being there in the moment.”

It’s a sentiment echoed by other Australian record-holders. David Mulheron is the Australian men’s record holder for Constant Weight Bifins, diving to a depth of 86m.

David initially came to the sport to improve his spearfishing capabilities. Now he’s not only a freediving instructor, but a competitor with 9.5L lungs – about one and a half times the average capacity.

David explains that it can be hard to find the right conditions for depth disciplines in Australia. The sport requires deep water where there are no currents to impede a vertical descent. For this reason, most Australian depth competitors need to compete overseas.

David’s solution was to move to Christmas Island, 1500km west of the Australian mainland, where he now runs a freediving school. “The ocean conditions are probably equal to the best freediving locations in the world,” David says. “We’ve got warm, clear water and the main thing is that we’ve got basically unlimited depths. We swim about 80m from the shore, and we’ve got 40m of depth. And then if you go another 100m out, you’re into 100m-plus depths, which is great for training.”

David says while he loves being in the water and the marine life interactions, freediving means more to him than that. “It’s the silence you can find in the water,” he says. “You can escape the crazy world we live in.” He continues, “On a deep dive, if your mind is in the right place, you shouldn’t really think of anything, you should basically just be on autopilot, hopefully in some sort of ‘flow’ state.”

Perhaps it’s this gift of just slowing down and being present, whether in competitive or recreational freediving, that is the crux of the addictive nature of the sport.

“I see it in students every week,” Kyra says. “They come into the course to get better at spending their time in the ocean. All of a sudden, with a bit of coaching, they’ve really engaged that ‘flow state’ of just being in that moment, not thinking of later or before. As soon as you have that moment, without your breath, you just feel really connected to any life around you or the life in the reef. It feels really primal to me, and that’s what I love.”