PART ONE – Sydney to Gundagai

Biting down on a flickering torch, with a dust-encrusted clay tobacco pipe in one hand and his camera in the other, Thomas Wielecki hauls himself up through a trapdoor at the historic Berrima Vault House. “This isn’t exactly what I had in mind when you told me we were going to drive the old Hume from Sydney to Melbourne,” the photographer says, as he plucks cobwebs from his hair.

After leaving Sydney this morning, the first couple of hours of our road trip unfolded like clockwork. We stopped to admire the exquisite workmanship of the heritage-listed Lansdowne Bridge near Fairfield, in south-western Sydney. Opened in 1836, the bridge features a sandstone arch with the largest span of any surviving masonry bridge in Australia. We then checked out the white concrete mileposts in the main street of Camden – relics from the time when the Hume Highway ran through the centre of town – and successfully negotiated the tortuous climb over the Razorback Range, near Picton.

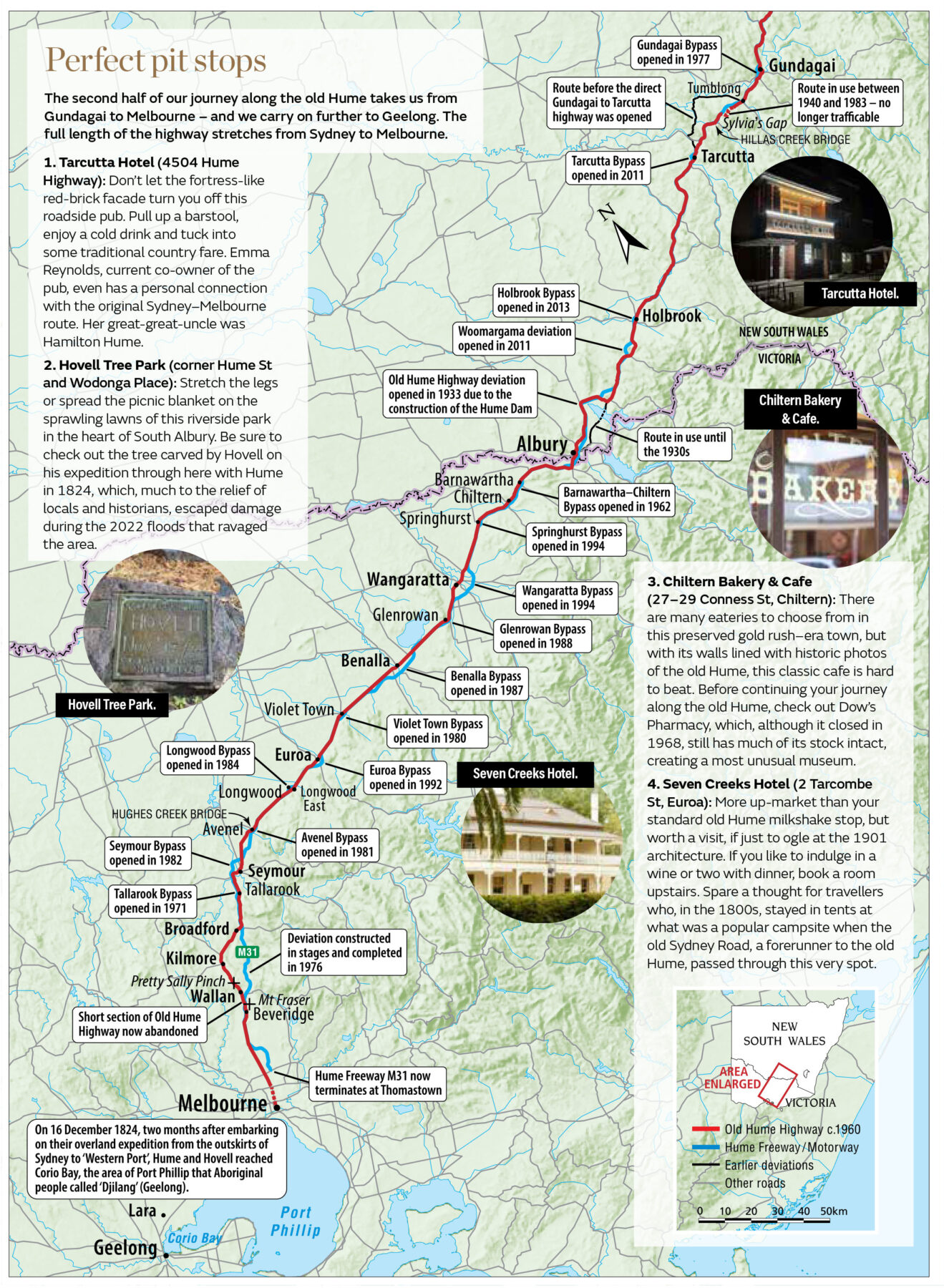

But after arriving in the historic hamlet of Berrima, we discover that when travelling the old Hume you need to expect the unexpected. Unlike the monotonous drive along the modern Hume Highway – which, since 2013, incorporates the Hume Freeway and Hume Motorway, and bypasses every town between Australia’s two largest cities, Sydney and Melbourne – exploring the old Hume is like launching into a choose-your-own-adventure story, especially if you’re willing to scratch the surface.

That’s exactly what we do at the Berrima Vault House. Built in 1844 as the Taylor’s Crown Inn, the landmark was recently transformed into an elegantly appointed country club. It’s open to the public from Thursday to Sunday, and event manager Gabby Hopping gives us a tour.

The underground spirit bar, cosy den and series of dining rooms – one of which is home to one of the biggest open fireplaces in the country – are all impressive. But it’s a small door enticingly labelled “Tunnel” that catches our attention.

“Dating back to the mid-1800s, there are stories of contraband being trafficked through a tunnel across to the jail on the other side of the road,” Gabby says. “During recent excavation works we discovered what might be its entrance – hardly anyone has been down there yet.”

That’s all the encouragement Thomas needs. He lowers himself into the tunnel entrance. “In the direction of the jail, it’s closed off with stone that looks like it’s been there a long time,” he says, showing us the photos he’s just captured.

Thomas’s chance discovery of a partially buried 19th-century clay tobacco pipe adds to our intrigue about what this space would have been used for, and who might have left the pipe here. There’s so much to discover along the old Hume.

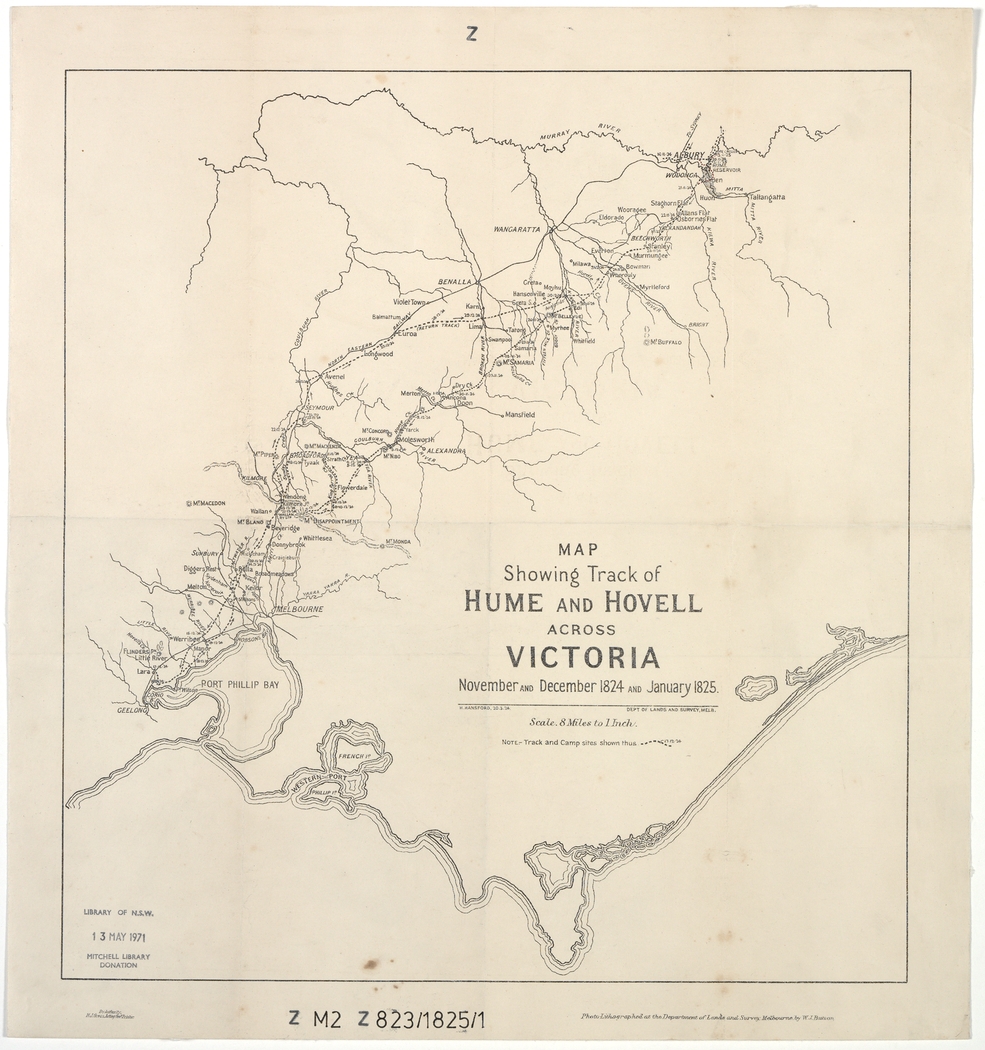

The old Hume Highway has had several monikers over the years. It was once known as the Great South Road in parts of New South Wales, and Sydney Road in Victoria. Indeed, it was only in 1928 that both state governments agreed to rename the entire inland route between Sydney and Melbourne the Hume Highway after NSW-born explorer Hamilton Hume. In 1824 Hume and William Hovell, an Englishman, were the first Europeans to travel the route. It wasn’t fully sealed until 1940. Later, in 1954, the road was signed National Route 31.

Sections that meander through now-bypassed towns such as Berrima are signposted and well maintained. But for the curious motorist who wants to follow as much of the original route as possible, finding it is often a case of hit or miss. Heading south, we soon discover stretches of the historic route that disappear without warning into paddocks or end abruptly at fences, grids or piles of blue metal, some with and others without “Road Closed” signs.

At one of these dead ends is Black Horse Farm. Despite the fact that the farm stands only 15m from today’s Hume Highway, not many modern-day travellers know about this former pub. Even fewer have visited. But it hasn’t always been like that.

Strategically built in 1835 at the junction of several roads, the famed watering hole – originally called the Black Horse Inn – was heavily frequented by passers-by, including many who harboured nefarious motives.

In fact, the Black Horse Inn was robbed so many times during the mid-1800s by bushrangers, including the notorious Ben Hall Gang, that police would hide in the bushes nearby waiting for the next robbery.

These days it’s a private home, where Christopher Dalton lives with a menagerie of horses and peacocks. “They arrested the bushranger Jackey Jackey [William Westwood] after a fight here in 1841,” Christopher says, leading us inside to where 19th-century travellers quenched their thirst. “His great-grandson even made a pilgrimage here recently to see where he was captured.”

Despite living here for much of his life, Christopher knows the building still holds secrets he has yet to uncover. Apparently, a cellar lies somewhere beneath the creaking floorboards. “But I’ve never found the entrance,” he says.

However, it’s another original building – carefully crafted stone stables – behind the house that is the real treasure. Now overgrown by Boston ivy, the stables feature open slit windows that were designed to be used to defend attacks by marauding bushrangers and other thieving criminals.

Christopher shows us around the stable buildings, which have fresh straw on the floor and feature rustic timber beams. “If only the walls could talk. Think of all the animals – and probably some people – who’ve sheltered here over the years,” Christopher says, shouting over the constant whir of traffic zooming along the Hume Highway.

Just south of Black Horse Farm is Hanging Rock Road, a rare stretch of very old Hume, where between 1864 and 1874 travellers paid a fee towards road maintenance at a toll bar. Bushrangers regularly fleeced the toll collector of his daily takings. Today, on the upgraded Hume Highway near here, there is a service centre.

Such modern mega service centres and their adjoining fast-food outlets have sucked the life out of many small towns, including Marulan, with a population of about 1200, just south of here. Its main street contains almost as many boarded-up shops as those with their doors open.

Even some of the bigger towns have fallen victim. Although many locals in Goulburn, which is one of the largest inland population centres in NSW, celebrated the opening of the bypass in 1992, the owners of the town’s Big Merino tourist attraction were less than impressed.

After missing out on the potential business of at least 40 busloads of tourists a day for 12 years, the iconic 15.2m-high, 97-tonne concrete ram was moved about 800m down the road in 2007 to the service centre on the town’s bypass.

Between Goulburn and Yass, we climb up the Cullarin Range, a notorious stretch of highway where, in the 18 months before it was bypassed in 1993, 29 people lost their lives in road accidents. Even today, old truckies talk of this horror stretch of the old Hume in hushed tones.

The Towrang Stockade

Behind the Derrick VC Rest Area, between Marulan and Goulburn, is an 1839 convict-built sandstone bridge, one of the most impressive remnants of the Great South Road, the forerunner to the Hume Highway. It’s best accessed via a two-minute walk from the signboard at the rest area. Like many bridges in this era, it’s thought to have been designed by master stonemason David Lennox.

However, the Towrang Stockade across the road is the real treasure here. From 1833 to 1843, the stockade was home to chain gangs of convicts who built the sandstone bridge by hand as well as many kilometres of the original road both north and south of it.

Life on the chain gang at the Towrang Stockade was tough. Convicts were subjected to rigid daily routines and harsh punishments. They earned up to 100 lashes for absconding and between 25 and 30 lashes for trivial offences such as talking to passing travellers.

Convicts wore leg irons, were chained together at night and forced to sleep in cramped transportable convict boxes with just one blanket each. Some desperate souls attempted to kill their fellow convicts in the hope they’d be sent back to jail in Sydney, where the food was purportedly much better, and the nights not as cold.

This heritage-listed site is recognised as one of the best remaining relics of penal road gangs in Australia. Visitors are welcome to visit several historic locations here, including:

The powder magazine

Built into the banks of the Wollondilly River, the blasting powder used for road cuttings and splitting building stone was stored here.

Gravesite

Although the graves of convicts who were killed in accidents during road construction or died of natural causes are unmarked, there are three headstones at this roadside cemetery, including one of a trooper and another of a trooper’s four-year-old daughter.

Troopers’ quarters

A fenced-off area marks the original site of the wooden and rubble quarters of the troopers, who guarded 100–250 convicts.

Breadalbane (population about 100) is the first town on the range. Opposite the pub, the only business in town, we notice a highway shield for Route 66 nailed to the brick wall of what appears to be a long-abandoned Shell service station. The 66 has been painted over with a 31.

“Sorry, there hasn’t been any fuel sold here for over 40 years,” Les Davies says as he emerges from the old workshop, now his storage shed. He points to the “No Petrol in town” sign flapping in the wind on the padlocked gate.

We’re driving an electric vehicle (EV), so aren’t in need of fuel, but we tell Les we’re following the old Hume and would love to take a photo of his Route 31 shield. “I love the old Hume; I can’t get enough of it,” he says, his frown transforming into a smile. He promptly unlocks the gate and invites us in for a tour of the former servo, which he and his partner Julie Chalmers have called home for 18 years.

“Although I’ve never been to the USA, it’s a shame our Route 31 isn’t promoted in the same way as their Route 66,” Les says. “I’ve ridden my Yami XT 600 along many stretches of the old Hume and often think how tough it must have been for Hume and Hovell when they came through in 1824.”

The old restaurant is now the couple’s lounge room where instead of dining booths there is a cinema-sized TV, wrap-around lounge, and floor-to-ceiling shelves crammed with thousands of DVDs, including more than a few about the legendary Route 66.

In their bedroom, taking pride of place on the wall, is the old fuse box that once controlled the bowsers and lighting on the forecourt. In another room, squirrelled away among even more Route 66 memorabilia, is a rare Spider beach buggy that Les has converted into a gaming console. Out the back, you can still see the big pit where they grew vegies for the former servo’s restaurant. “We came out here [from Sydney] to escape the rat race,” Les says. “The fact we found an old servo was just a bonus. We love it here; it’s so quiet.”

From Breadalbane, there are two possible routes into Gunning: the sealed old Hume, which was the main highway here between 1940 and 1993, and its predecessor, the old old Hume, or unsealed Sydney Road. At times they run parallel to each other, only metres apart, and at other points on the long climb up the range they criss-cross over the tracks of the Main Southern Railway. We choose the bitumen.

It’s the right choice. This is the old Hume I’d dreamt about: a narrow sliver of silver snaking through paddocks dotted with bleating sheep, overgrown verges, moody skies, and no other cars within cooee.

Thomas opens the sunroof and puts his foot down, but not for long. Here, the bridges aren’t named after dignitaries but rather after the loads lost by trucks that toppled over on the road’s very tight corners. First, there’s Biscuit Bridge. Next is Champagne Corner.

It’s a bit further along the windswept plateau at the top of the Cullarin Range that, on 17 October 1824, Hume and Hovell set out from Wooloowandella, a property Hume had bought several years earlier. Their journey to Melbourne had begun on 3 October 1824, when the men left Hume’s farm at Appin, on the outskirts of Sydney. There’s also a commemorative cairn at Appin, but it wasn’t until the explorers left this very spot at the top of the Cullarin Range that their adventure truly began. From here, they headed into country that for European settlers was regarded as “beyond the limits of civilisation”.

Part of Hume’s far-flung outpost was later purchased by his brother John Kennedy Hume, who changed its name to Collingwood, apparently because of his admiration for Admiral Collingwood of the Royal Navy. During the 20th century, the sign at the property’s entrance was often pilfered by supporters of the Collingwood AFL team. Replacements were subsequently made smaller and smaller and today the lettering on the sign is so faint you almost need a magnifying glass to read it.

The quarrelling explorers

It’s no secret that Australian-born Hamilton Hume and Captain William Hovell, a former British sea captain, weren’t the best of mates. They saw themselves as rivals and quarrelled for much of their 1824 journey from Appin to Port Phillip Bay (now Port Phillip).

At the Goodradigbee River near the Snowy Mountains, Hume and Hovell temporarily split up their party after arguing about their route. They divided all their provisions. Robert Macklin writes in his 2017 book, Hamilton Hume: Our Greatest Explorer, that, “as both lay claim to the single tent, they were on the point of cutting it in half when Hume realised the futility of the act and let Hovell have it”. Apparently, the pair even fought over the frying pan, which broke apart in their hands. Hovell, realising his navigation error, eventually rejoined Hume for the journey south.

In the years after the expedition, their spat became public. Hume was especially miffed that Hovell would jump at opportunities to take sole credit for discovering the overland route to Melbourne. In fact, during a trip to Geelong in 1853, Hovell was lauded as “the man who discovered” that route. Hume responded angrily by publishing his Brief Statement of Facts, which Macklin describes as “a broad-brush account of the expedition” that “detailed Hovell’s recalcitrance and backed it with damning detail from other members of the [expedition] party”.

The two continued to trade barbs publicly until Hume’s death in 1873. Not only did Hume design his own tombstone in the Anglican Section of the Yass Cemetery, but in the last months of his life he also penned his own epitaph.

His main concerns were the preservation of his family’s name and the regard in which history would hold him. He wrote: “For the sake of those who bear my name, I should wish it to be held in remembrance as that of one who, with small opportunities but limited resources, did what he could for his native land.”

After a long day behind the wheel, we arrive in Gunning and are tempted to bunk down in the renovated London House, built c.1881. It’s an elegant brick building with an arched coach entrance dating back to the days of Cobb & Co. However, enticed by a sign boasting push button telephones, a TV and a pool, we check in to Motel Gunning instead.

What a masterstroke. This place is retro without trying to be. The clock radios look as though they were plucked straight from a 1978 Tandy Electronics catalogue, and the air conditioner thumps and whirrs all night like a worn wheel bearing on a B-double. No chance of hearing any road traffic over that. As for the phone and pool, both are long gone. The latter is now just a partially filled depression in the ground. But we wouldn’t have it any other way. Our digs are everything the old Hume is – a delightfully dated reminder of a bygone era.

The next morning, not far along the main street of Gunning, we unexpectedly find an EV charging point outside Bailey’s Garage, an old-school service station complete with a wonderfully cluttered workshop. Owner and mechanic Craig Southwell spots us admiring the historic facade. “We get lots of people stopping here for photos,” he says, pointing to a mural featuring old Holden cars that extends along the entire length of the building. “To think horse and carts used to pull up here,” Craig says, looking at our EV.

Craig is softly spoken, articulate and on the weekends doubles as the town’s lay preacher. Although his family bought the garage during the 1940s, they decided to keep the Bailey’s name as a nod to the first owner. “Back in the 1970s, I repainted the name of the garage in an old-style font,” he says. “It just felt right.”

Born and bred in Gunning, Craig clearly remembers the first night the town was bypassed in 1993. “I heard a train come through and it completely freaked me out. I’d never heard a train before because the trucks grumbling through town 24/7 were so noisy,” he says.

The hidden treasure

Just south of Berrima is the Mackey VC Rest Area. At first glance it looks like any other roadside stop along the Hume Highway, with a toilet best avoided unless absolutely necessary and the ground strewn with fast-food wrappers.

However, if you walk behind the parking area, there is a section of the paved old Hume that runs back towards Sydney. About 200m along and traversing a modest-sized rocky gorge is one of the highway’s oldest – and arguably most impressive – bridges.

Designed by master stonemason David Lennox, the bridge was first built in 1836 as a timber beam structure supported by sandstone abutments. It was replaced in 1860 and then again in 1896 by a concrete arch, supported by the original sandstone abutments and retaining walls that have well and truly stood the test of time.

If you look closely, you can even see a flight of hand-carved steps that lead down to a waterhole on Black Bobs Creek. In the 1800s this would have been a reliable water source for thirsty horses and later for overheating car engines. Today, it’s a tranquil spot to sit and reflect on all those who’ve made the journey down the old Hume in different modes of transport across many generations. Do take care though; the stairs can be slippery and the parapets are in urgent need of repair.

About halfway to Yass the road passes over Hovells Creek Bridge, one of few places along the entire route named after William Hovell. Most are named after Hume. In fact, about 30km down the road, in Yass, almost everything has Hume in its name, from the drycleaner to the tennis courts. Ironically, one of the few places in Yass not carrying Hume’s name is Cooma Cottage, where he moved with his wife, Elizabeth, in 1840, having apparently camped there with Hovell on 18 October 1824, the day after they left Wooloowandella.

Not only did Hume live out his final days on this riverside property, but the very highway later named after him ran by his front door…and later, by his back door. When the cottage was first built in 1835, the main track south traversed the paddock fronting the Yass River, so the dwelling was designed with its front door facing the road. However, soon after Hume moved in, the road was re-routed to the other side of the property, prompting him to engage in extensive renovations, including adding a classical Greek-revival portico facing the passing traffic. Today, Cooma Cottage is a museum managed by the National Trust.

South of Yass is Bookham, which, in 1839, poet Banjo Paterson mentioned in his memoir in The Sydney Morning Herald. He described it as a town with a pub at each end and not much in between. Paterson’s statement remains accurate, except that both pubs are now long closed. The town was bypassed in 1998.

The upgraded Hume Highway split what was left of the town in two, and today locals have to brave a walk through a tunnel under the busy freeway to access the recreation ground. Unlike in Berrima, you won’t find any antique pipes on the ground here – just cigarette butts and more of those omnipresent fast-food wrappers.

Although some smaller towns along the old Hume have struggled to find their feet since being bypassed, one place that is booming is Jugiong. But it wasn’t always that way. After it was bypassed in 1995, the town suffered. However, in 2016, mother–daughter duo Liz Prater and Kate Hufton purchased the Sir George, a dilapidated country pub, and breathed life back into Jugiong. In just five years, the pair transformed the pub, which was originally built in 1852, into something you’d expect to see in Sydney’s Double Bay or Melbourne’s Toorak. It now features an upmarket restaurant, artisan bakery and chic heritage overnight accommodation in the restored original stables.

Across from the Sir George is a lonely statue of Sergeant Edmund Parry, who was killed near here by bushranger Johnny Gilbert in 1864. A shiny new interpretive sign details the mid-1800s tussle, describing it as “The Battle for the Roads”. Today, the only battle here is a nightly one, fought among grey nomads who flock to the adjoining showground to score a spot at the free camping ground, the perfect place to recuperate before heading further south, along the road to Gundagai.

PART TWO – Gundagai to Melbourne and beyond

I grip my seatbelt tighter and exclaim “Whoa!” Looming large ahead are several feed bins strewn across the bitumen. It’s not that I needed to worry, because my travelling companion, 76-year-old Jim Morton, expertly manoeuvres his turquoise 1964 EH Holden around the unexpected obstacles on the old Hume Highway. Thankfully, there are no semi-trailers hurtling towards us. In fact, the only other traffic we need to watch out for is a mob of sheep playing follow the leader around the next bend. Oh, and there are also a couple of fat cows that briefly raise their heads as we motor past.

But it wasn’t always as quiet here on this stretch of the old Hume, just south of Gundagai, which is now on private land. It was once bumper to bumper with trucks chortling and snorting their way along the most dangerous few miles between Australia’s two largest cities.

Jim suddenly stops. Around the next bend a tree branch has fallen right across the faded double yellow lines. I jump out and, as if I’m pulling a kangaroo carcass off the road by the tail, drag it clear. On the verge is one of those yellow 44-gallon rubbish drums, once common at highway rest areas. The paint is peeling off in sheets and it’s pockmarked with bullet holes. It swings in the howling southerly, squealing on rusted hinges like a B-double engine in urgent need of a tune-up. I peek inside: there’s a stash of sun-bleached 40-year-old soft drink cans. Talk about a time capsule. It’s a future archaeologist’s delight.

“I doubt anyone has stopped here since ‘the Gap’ was bypassed in 1983,” says Jim, who has access to this historic route and is treating me and Thomas to the ultimate drive back in time. The Gap is Sylvia’s Gap, a terrifying two-lane crumbling bitumen track flanked by sheer rock walls that for almost 50 years carried all the traffic between Sydney and Melbourne. No-one knows the off-camber blind bends on this highway better than Jim, who, as a fresh faced 18-year-old, first negotiated Sylvia’s Gap in a 1952 Chevrolet. “Back when it was a seven-hour drive to Sydney,” he says. “Now it takes half that.”

That was during the 1970s and ’80s when, as part of his construction business, Jim regularly undertook road maintenance for the New South Wales Department of Main Roads, which included helping to clear accident scenes at the Gap. “The truckies could have shaken hands with each other as they passed through here,” he says as he steers his beloved EH through the infamous cutting.

Suddenly he hits the brakes again. This time he remains silent. As he scratches his chin, deep in thought, I swear I can almost hear the ghostly echoes of airbrakes and downshifting gears. Or is it just the wind?

“Sadly, not all of them made it through,” Jim eventually says with a sigh. “Just beyond here is the 40-foot gap – a graveyard for big rigs. I’d get calls at all times of the day and night…there was a lot of death and heartache here.”

He’s not half wrong. During a terrible two-week period in 1981, seven fatal accidents occurred at Sylvia’s Gap. There are still rusting wrecks in the gullies below.

A few hundred metres short of where the old road meets up with the double-lane modern Hume, we reach another locked gate. It’s time to bid farewell to Jim and his vintage EH and continue our journey south in our much quieter electric vehicle. Even the cows don’t notice us this time as we snake our way back out of Sylvia’s Gap.

If you’re attempting to follow the old Hume south of Gundagai, you need to be prepared for a series of abrupt dead-ends – either piles of dirt blocking the way ahead or padlocked gates with signs, almost always misspelt, and screaming “Trespassers will be prosecuted!” You’ve also got to have your wits about you, because over time some towns have changed their name. When we step inside a historic hotel with Adelong Crossing plastered (albeit in faded paint) across its brick facade, the bartender takes a while to convince us we are at Tumblong. “The name changed in 1913 due to increasing confusion with the town of Adelong, which had sprung up in the goldfields [25km away from the Snowies],” he explains.

There’s no mistake, however, about where we are when we drive into Tarcutta – regarded as the halfway point between Sydney and Melbourne. It was here, in 1838, long before the route was called the Hume (in the 1920s) where the first mounted postie from Sydney met his Melbourne counterpart to exchange mailbags before retracing his steps back along Great South Road.

As the track became busier, Tarcutta prospered as a convenient halfway stop for weary travellers. So when it was bypassed in 2011, many locals were worried their town of 400 (on a good day) might die a slow death. Greeted by a dust-encrusted tumbleweed blowing past a row of boarded-up shops, it seems at first glance their fears were warranted. Eventually another vehicle pulls up behind us. It’s long-time local builder Bill Plum, checking his tools are properly tied down in his ute before hitting the freeway.

After finishing a short stint working on Queensland’s Sunshine Coast, Bill tells us, he was quick to return to Tarcutta. “I like the pace of life here; it’s much slower,” he says, adding, “And houses are much more affordable.” I bet they are. Bill says the abandoned cafe behind us was once the thriving centre of town: “Back in the 1950s and ’60s, customers were often five deep waiting for a feed, and the main street here was lined with trucks for as far as the eye can see.”

Bill encourages us to wander across the road to the Australian Truck Drivers Memorial. “It’s dedicated to the memory of truck drivers who have been killed on Australian roads while performing their duties in the transport industry”, he says, clearly proud of the recognition his home town has afforded these poor souls who met such untimely ends.

“Check out the hundreds of names dating back to last century,” says my travelling companion, Thomas, as he circles the memorial. Hot on the heels of Sylvia’s Gap, it’s another reminder that although touring down the old Hume might be more romantic than zooming along the modern dual carriageway, it was, in its heyday – like many single-lane highways – a death trap.

South of Tarcutta, Holbrook, the last town on the Hume to be bypassed (in 2013), is thriving, thanks mainly to a seemingly out-of-place submarine plonked here in a park. Holbrook ditched its former name of Germanton during World War I to honour local Victoria Cross winner Lieutenant Norman Holbrook. He piloted his submarine on a daring raid through the Dardanelles’ minefields and torpedoed a Turkish battleship. Recognising the town’s submariner link, the Royal Australian Navy donated the decommissioned HMAS Otway to Holbrook in 1995.

Colin Bickley, who has a workshop in an old flour mill that “gets internal combustion vehicles back on the road”, says things in Holbrook have changed for the better since the bypass, despite there being less breakdown business. “You no longer have to dodge a constant stream of traffic when crossing the road,” he says, as we stop to photograph an oversized Route 31 shield outside his workshop. Colin offers us a parting word of warning for our journey further south. “If you want to follow [the old road] towards the border, I hope your EV has a submersible feature,” he says, laughing. “The old road runs along the bottom of Lake Hume.”

This historic route is sadly not sign-posted, but following Colin’s mud map we eventually pick up remnants of the old Sydney Road on approach to the sunken old town of Bowna. The only clue this was once the main artery linking Australia’s largest two cities is a shallow depression in a paddock…and a dilapidated, barely legible, black-and-yellow Lane Closed sign loosely tied to a gate. Classic old Hume: hard to find and unassuming.

Peering across a near-full lake, I can’t help but wonder how explorers Hamilton Hume and William Hovell, who, two centuries ago, carved out the route from Sydney to Port Phillip, would have reacted if they knew this valley would one day be drowned for irrigation, hydropower and flood mitigation. I’m sure Hume, who until his death sought constant recognition for his “leading role” in the expedition, would be overjoyed the lake was named in his honour. But he’d be turning in his grave for a couple of reasons at Hovell Tree Park in nearby Albury. First, taking pride of place in the popular park on the banks of the Murray River is a senescent river red gum known as Hovell’s Tree. Although both men carved their names on trees here when heading south on 17 November 1824, Hume’s was unfortunately burnt in the 1840s.

Second, there’s the river, which Hume initially named Hume River after his father, although several years later Captain Charles Sturt, not realising it was the same river, named it after Sir George Murray, secretary of state for war and the colonies. The new name stuck and washed away recognition of Hume’s father.

The ongoing tension between the two explorers was highlighted earlier in Part 1 of this two-part story. At one point during their expedition near the Snowy Mountains, the pair temporarily separated and attempted to split their belongings in half, including (absurdly) the last frying pan.

Ironically, the old Hume section across the border (most Victorians call it Old Hume Highway 31, or simply old Highway 31), which connects Barnawartha to Chiltern and now features shiny new replica mile posts, begins near Fryingpan Creek, a nod to the common cookware carried by gold diggers, not the explorers’ feud.

Hidden among gum trees at the 172-mile post (measured from Melbourne) is the unpretentious entrance to a motor museum. At the end of its driveway there’s shed after shed crammed with road and motoring memorabilia. One shed alone has more than 70 hand-operated petrol pumps, signs, bottles and racks, oil engines, tins, and even an incomplete set of Sidchrome spanners. It must be worth a fortune.

Curiously, there are also several mummified rats on display, “Oh, I found them on the floor,” says owner Gordon Stephens. When asked if any of his thousands of exhibits (including the rats) are for sale, he responds curtly: “No, never.” Hoarder, or sage collector? You decide. Just call ahead because he’s only open by appointment.

Chiltern is one of those heritage towns you might whisk your partner to for a weekend away, emerging only from a quaint B&B to admire antiques and quaff fine wine. It’s home to the Chiltern Bakery and its famous pies, and what road trip is complete without at least one serve of such a highway staple?

While queuing for our beef and mushroom pies, we spot several framed photos of now-gone old Hume landmarks in their heyday hanging on the wall, including the Prince Alfred Bridge at Gundagai and Hillas Creek Bridge, near Tarcutta. Forget the tomato sauce; accept instead the generous dollop of motoring nostalgia that comes with your pie.

The building’s owner, Adrian Gray, is an old Hume tragic. His family ran a mechanical workshop and petrol station in Chiltern from 1932 until it was sold in 1980. “We were also the RACV service depot, operated the local taxi [a Morris Oxford, only recently sold] and wedding/funeral car [a Plymouth Custom 6, still running smoothly], as well as tow-truck service,” Adrian reveals.

Look who knocked on the door at midnight

The clock had just ticked past 12 on a cold August evening in 1942 during the depths of World War II when, according to Gundagai folklore, Jack Castrission, co-owner of the town’s Niagara Cafe, received an unexpected knock on the door.

“He’d just closed up the cafe and was in the kitchen cleaning up,” recalls his son, Peter. When Jack opened the door, a well-dressed chauffeur announced, “I’ve got four hungry men in the car. I know it’s late, but can we please get a meal?” The men were Prime Minister John Curtin (1941–45), future PM Ben Chifley (1945–49), past PM Arthur Fadden (1941) and future senator Neil O’Sullivan (1946–62), who were returning from a morale-boosting mission in the region. “Dad invited them into the kitchen where they huddled around the fire while he knocked them up a feed of steak and eggs, washed down with tea,” Peter recalls. “Jack, realising he had the ear of half the war cabinet, mentioned his wartime rations of 12.7kg of tea per month were a tad inadequate. Several weeks later, the Niagara’s tea ration was mysteriously raised to 45kg per month.” Curtin returned several times to the cafe during the war, Peter says, and once “secretly shouted lunch for a group of Australian troops”.

Now, no trip down the old Hume is complete without settling into a booth at the Niagara for a burger and soda. It was in the Castrission family for six decades, then the Loukassis family from 1983. In 2021 Sydney couple Luke Walton and Kym Fraser took it on, renovating the Art Deco cafe back to its glory days. The duo lovingly restored the interior, including its priceless fountain bar and beaten-up booths, and sent the iconic rooftop neon sign to Sydney for a spruce-up. Locals have embraced the revamped Niagara, and after a pandemic-induced hiatus, travellers are returning in droves. “We’ve seen a yearning for nostalgia but also heard many stories from travellers revisiting the town and seeking to engage with the old Hume on a deeper level than a simple drive-by,” Luke says.

We discover it was Adrian, along with fellow old Hume enthusiast Peter Gaston, who was responsible for the replica highway markers and shields we’d just passed on the road from Barnawartha. “Most people just don’t know where the old highway is. There’s no guidebook, so we decided to take matters into our own hands,” says Adrian, who, with assistance from local tourism authorities, funded and then erected the replica markers in 2018. “First the signs on the freeway encouraging motorists to turn into Chiltern were knocked off, and then the pandemic hit. So interest in following the old highway hasn’t been as strong as we’d hoped.”

It would be futile erecting the historic mile markers south of here, because the next 300km or so through Wangaratta and towards Melbourne may as well be called the Kelly Way. Yes, we are now in Ned Kelly country and there’s absolutely no escaping it.

The epicentre is, of course, Glenrowan, the place of Ned’s last stand. There, under the gaze of the garish Big Ned, you can buy every Ned trinket you can imagine – not just key rings and T-shirts, but also toilet-roll holders and garden gnomes. More importantly, you can also indulge in a Ned Burger and, of course, wash it down with Ned Beer.

“Why is there so much fuss about him? He was a crook, wasn’t he?” I dare to suggest to Thomas, who has selflessly volunteered to do most of the driving while I attempt to juggle a smorgasbord of pies and burgers in the passenger seat.

“Shh! You can’t say that in these parts, you’ll get lynched!” he exclaims, quickly glancing in the rear-view mirror before planting his foot firmly on the accelerator.

Phew! At least we got out of town in one piece. Of course, poor Ned wasn’t so lucky. He was shot, captured and shipped off to the hangman’s noose in Melbourne.

Undoubtedly, one of the best things about travelling the old Hume is you avoid those ubiquitous service centres dotted along modern highways. Dreary, dirty and downright hectic, they’re the very antithesis of the old Hume pit stops.

Give me welcoming ports of call like the Seven Creeks Hotel in Euroa (bypassed in 1992) any day. What began with a couple of enterprising locals peddling goods to the passing parade of traffic on the old Sydney Road in 1853 has since evolved into an impressive Federation-style two-storey pub that dishes up scrumptious tucker and genuine country hospitality. No multinational eateries with hiked-up prices here. However, beware when pulling up a bar stool that you may well encounter the odd Kelly fanatic, no doubt exhausted from combing the streets of Euroa’s CBD in search of the National Bank, which the Kelly Gang held up in 1878.

Best not tell them it was demolished and replaced by another building in 1974.

In a way, the phantom bank is a symbol for the old Hume in many parts of central Victoria, where the old track has simply been superseded with the new Hume directly on top of it. If you follow one of these stretches about 15km south, you’ll get to Longwood…and Longwood East.

First cobbled together on the old highway as a staging post for horsedrawn coaches, the original town was moved 4km west when the railway arrived in 1872. Today, the modern Hume cuts through a wedge of farmland between both villages, its constant hum a far cry from the days in Longwood East (that’s the old village), when the sound of bleating sheep would only be broken by the occasional bugle alerting the local toll gatekeeper that a coach was approaching.

Another old Hume town impacted by the advent of the rail is Avenel, which first sprang up around the 1857 historic coach stop (now a private residence) on the southern banks of Hughes Creek. It later moved west, when, as occurred in Longwood, the railway arrived in 1872.

Spanning the creek near the old coach house is a spectacular six-arch sandstone bridge. Despite carrying all the road traffic – from horsedrawn coaches to motor cars and semi-trailers, from when it opened in 1859 until it was closed a century later – this engineering treasure is in remarkably good condition. What’s better is you’re allowed to walk on it.

While strolling past one of the peppercorn tree–shaded abutments, we meet 75-year-old local Wayne Henderson and Maggie, his four-year-old Maltese/Shih Tzu, on their daily constitutional. “She’s taking me for a walk,” Wayne says with a laugh, desperately trying to keep up with his energetic canine companion. Wayne manages to hold Maggie back long enough to tell us about “the good ol’ days” travelling over the bridge as a child in his dad’s car “with no air-con and when the Hume was just one long line of traffic”. Mmm… sounds like the “good ol’ days” are overrated.

However, even here, on this now off-the-beaten-track bridge, there’s no escaping Ned. When he was only 10 years old, just downstream from here, he famously rescued primary schooler Richard Shelton after he accidentally fell into the creek while walking to school. “Ned dragged him onto the bank, got him breathing, and then just rode off,” says Wayne, adding, “I generally think Ned was a villain, but he must have had some goodness in him to make sure he was alright.”

Shelton’s parents were so grateful they presented Ned with a seven-foot-long green sash, a gift cherished by the bushranger for the rest of his short life. In fact, after being shot and captured at Glenrowan, a doctor found the badly bloodstained sash under his infamous armour.

A tale of two bridges

The modern and much safer Hume Highway not only bypasses many historic towns but also some of Australia’s best-loved bridges.

These include several notable 19th-century stone crossings that, although now well and truly off the beaten track, still span several creeks and gorges between Sydney and Gundagai (as featured in Part 1). The old Hume further south also boasts its fair share of eye-catching bridges, including the impressive six-arch sandstone engineering feat at Avenel (see page 78), as well as these two landmark crossings at Gundagai and Mundarlo (near Tarcutta).

Prince Alfred Bridge

For more than 150 years, this timber-and-wrought-iron connection between Gundagai and South Gundagai stood proud, stretching across the Murrumbidgee floodplain. For locals who’d just been issued their drivers licence, crossing Prince Alfred Bridge was a rite of passage.

For travellers, it was a rollicking teeth-rattling, bum-clenching 900m-long ride, braving vibrating timber planks that agitated with each passing vehicle. It’s a national tragedy that this clatter wasn’t recorded and squirrelled away in the National Film and Sound Archive for future generations to appreciate. In 1984 the bridge was closed to traffic, and, following ongoing safety concerns, it was partially demolished in 2021. Apart from a short section at the southern end of the crossing, all that remains are remnants of timber posts, sawn off at waist level. Today, these extend across the floodplain like a procession of tombstones – a constant reminder nothing lasts forever, even on the old Hume.

Hillas Creek Bridge (Pictured)

When this attractive arch crossing, designed by engineers who pioneered the use of the bowstring shape in reinforced concrete, was opened in 1938, its appearance quickly earned it the moniker “Little Sydney Harbour Bridge”. It was listed on the Register of Australian Historic Bridges in 1982, just a few years before it was bypassed. When travelling north on the modern Hume, if you look to the left (north-west) just before you cross Hillas Creek, depending on the season, you can sometimes spot the old bridge through a copse of deciduous trees. If you’re in the passenger seat, look closely at how narrow the bridge deck is – little wonder that more than a few trucks lost side mirrors when passing other vehicles here.

Many stretches of the old Hume have nicknames, most bestowed by truckies. There’s Gasoline Alley in Yass, where trucks stopped to refuel, and Champagne Corner, where a semi lost a load of alcohol near Breadalbane. And don’t forget Sylvia’s Gap near Gundagai. That was apparently named after a lady of ill repute. You get the drift.

Just out of Wallan, the pinch, which straddles the top of the Great Dividing Range, is called Pretty Sally. Travellers and truckies have long speculated about the origin of the name of this hill. But it’s generally accepted it’s so-called after a Sally White who operated a nearby shanty in the 1840s where drivers refreshed themselves and spelled their bullocks or horses before tackling the steep hill.

According to Peter Williams, who arranges convoys of Minis along the old Hume and who has researched many of the curiously named locations, “She was said to be as ugly as sin, so what’s more natural than to call her ‘Pretty Sally’?”

It’s been a long, hot day with relentlessly blue skies so bright they hurt the eyes. But approaching dusk near Beveridge, there’s smoke and dust hanging low in the atmosphere and we can just make out the sea in the distance, if we squint. This would have been a similar view to that enjoyed by Hume and Hovell, who, on 14 December 1824, caught their first glimpse of the briny from the top of a nearby hill, now called Mt Fraser.

From here, purists would follow the old Hume along Elizabeth Street and into the centre of Melbourne – yes, in the shadow of Old Melbourne Gaol, where Ned was hanged on 11 November 1880. But instead we track towards Geelong, near where, on 16 December 1824, Hume and Hovell mistakenly believed they’d reached Western Port but had in fact reached their turn-around point at Point Wilson or, more probably, Point Lillias.

Just short of here is the last stone cairn that marks the route of the Hume and Hovell expedition, this one on the outskirts of Lara. It’s on the verge and most drivers zoom past. But we don’t. We stop and ponder on the 1000 or so kilometres we’ve journeyed from a similar cairn near Appin, just south of Sydney, that bookends their expedition route.

The old road – with its well-worn ruts carved out by gold escorts and skid marks left by terrified truckies who for more than a century ran a nightly gauntlet along a narrow strip of broken bitumen and cracked concrete – is gone. It’s been replaced with the hidden Hume, which in places is hard to find, and even harder to follow. It’s a choose-your-own-adventure at every turn, a road trip where Australia’s last 200 years is laid bare, just waiting for you to discover. While it may harbour a potted past, as more travellers choose to bypass the bypasses, its legend will continue to grow. Just don’t mention Ned.

We thank Hyundai for providing an Ioniq 5 EV for this story.