As the light faded at the end of a long day of riding, I flicked on the LED headlights of my all-terrain vehicle (ATV) so I could see better as we meandered in convoy through a tunnel of dense vegetation. The rainforest is reclaiming the track from all directions in this remote, rarely accessed part of Cape York Peninsula in far north Queensland. A voice over my two-way radio let me know we had conquered the last ridge, just as we started our descent to the coast. Despite the dark, I noticed a change in the vegetation from lush vines and a dense canopy to a more windswept coastal environment. The track soon leveled out and I could feel soft sand beneath the ATV’s tyres that signalled the coast was close.

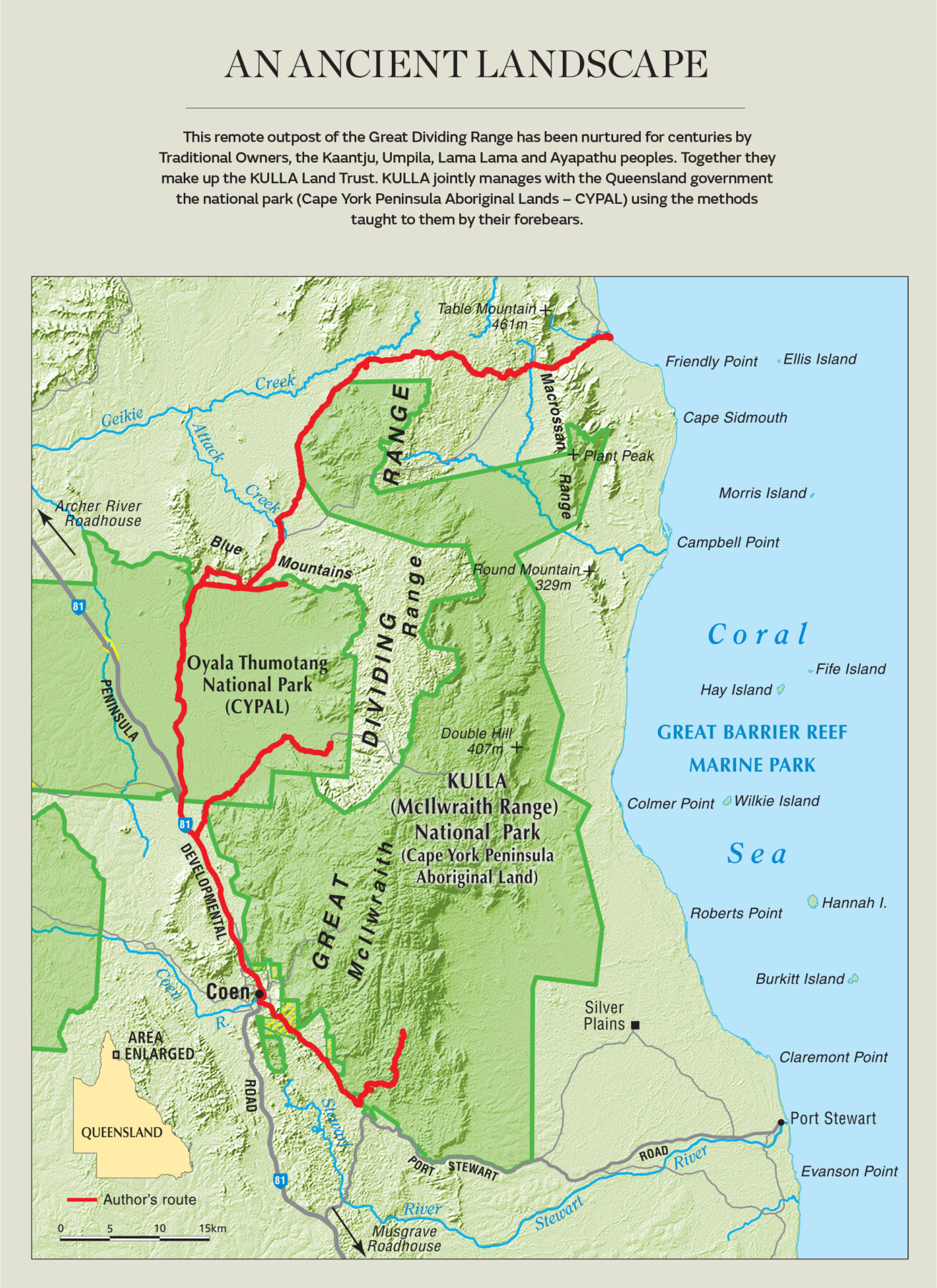

There are very few places in Australia that feel as far away, rugged, and ancient as the McIlwraith Range. Covering about 3000sq.km, this part of Cape York Peninsula lies roughly 15km east of Coen and 550km north of Cairns. The landscape here is punctuated by peaks – the highest of which reaches 824m – that form part of the Great Dividing Range. These support rainforests that cascade down escarpments and into valleys where rich river systems flow, separating vast open areas of bushland. The rainforests here are the wettest and most elevated on the Cape, offering refuge to a number of endemic species. They have close ties to the tropical rainforests of New Guinea and represent the southernmost limit for some of the plants and animals found there. Among the best known of these are the spotted cuscus, the green tree python and the palm cockatoo, with its distinctive black plumage, red cheek patches and a shrieking call that cuts through the forest.

I was lucky to be traversing this landscape under the guidance of Traditional Owners Dion Creek and Amos Hobson, brothers from Southern Kaantju and Uutaanlanu countries, and this area can’t be accessed in any other way. It was pitch dark when we arrived at the coast and set up camp, exhausted after a long day of riding. It wasn’t until morning that I could take in the full spectacle of this pristine natural landscape, when the dawn light revealed a sprawling beach lapped by the sparkling turquoise waters of the Coral Sea, and to the north, a wide river mouth teeming with fish. I felt privileged to be there and humbled that Dion and Amos had shared their connection to Country and coast with me throughout the journey.

“Our Kaantju Country straddles all the high country of the McIlwraith Range. It’s healthy and pristine because it still has our presence; for thousands of generations we have been here, looking after our Country,” Dion explained months earlier, as we sat together perusing maps, planning our expedition.

Our mission was simple: to see and experience as much of KULLA (McIlwraith Range) National Park (Cape York Peninsula Aboriginal Land) as we could in seven days and to document what we saw. Jointly managed by the KULLA Land Trust and the Queensland government, the park is made up of country belonging to the Kaantju, Umpila, Lama Lama, and Ayapathu peoples – the name KULLA is an acronym for these groups’ names.

Our plan was to explore the highland areas of the park first, before undertaking a 200km round trip to the coast along the northern foothills of the range. Given the park’s remoteness, the extreme nature of its landscapes, and the rough condition of its tracks, we’d need the ATVs. These lightweight four-wheel-drives can go places most conventional 4WDs simply can’t. But because they’re small, they have limited range and capacity for carrying supplies. Our fuel, water, food, spare tyres, first aid equipment, tools and camping gear would need to be spread out among our team members. The team comprised Leon Kyle – logistics coordinator and mechanic; Darrock McMonnies – lead rider and videographer; and me – expedition leader, drone pilot and photographer. Jameel Kaderbhai also joined us as an additional photographer and drone pilot for part of the expedition.

After months of preparation, including test riding and scenario planning for potential helicopter evacuation, we finally met up with Dion, Amos and their crew in Coen in August 2022 to set off on our expedition. Their side-by-side vehicles, slightly larger ATVs than ours, were packed with supplies and gear, and the brothers were accompanied by a group of young enthusiastic rangers who were keen to explore and show us the mighty McIlwraith.

Our first forays into the highlands were slow-going. Overgrown tracks, fallen trees and hot conditions limited how far we could venture during daytrips. As we climbed and descended through the undulating terrain, we passed through dry sclerophyll forest and dense rainforest, reaching very few vantage points. This made it difficult to gain a perspective on just how impressive the McIlwraith Range truly is. Dion, who has guided many research teams through the range over the years, explained that the only real way to appreciate the scale and uniqueness of the area is by helicopter. Our drone offered us a means of capturing the occasional bird’s-eye view, and we snatched glimpses when the canopy allowed.

During our last day in the highlands, we reached a stunningly beautiful rainforest creek. Dion instantly lit a fire in anticipation of the haul of black bream the rangers would catch with their handlines. It didn’t take long before we were all feasting on the delicious fat fish, a wonderful end to the first phase of our expedition.

After three days in the highlands, we set off for the coast. As the landscape opened up, I felt an instant sense of awe. Under a big blue sky lined with wispy clouds, eucalypts studded the landscape, and flocks of birds flew towards the distant horizon. The landscape, covered in sparse bushland, gave way to patches of lush rainforest vegetation as we dropped into valleys or climbed mountain slopes. Wide sandy riverbeds and deep creek crossings provided challenges aplenty for us with our ATVs as we plotted a course through the foothills. Dion and Amos navigated Country intuitively, without the need for maps or GPS guidance. Aware of even the most minor vegetation changes and geological landmarks, they connected to Country through stories, and weaved a seamless track across hundreds of kilometres.

“Kaantju people have maintained an unbroken connection to Country for thousands of years and my grandfather handed down the knowledge of how to look after his Kaantju Country,” Dion said. “We believe Country can only be healthy if we, the First Nations Traditional Owners, are on it, visiting the special places at the right time each year and looking after it as best we can. This keeps our culture alive, keeps us healthy and keeps Country alive.”

The landscape was unforgiving and conditions were hot. We had limited access to fresh water – at times, water sources were 30–40km apart, but Dion and Amos were always confident in finding them. The going was tough on both ATVs and riders – there were no smooth sections of track. There were fallen trees aplenty, as well as sticks and spiky vines to avoid. We navigated through muddy entries and exits to water crossings, over steep and loose riverbanks, and across soft sandy beaches. The terrain was uneven, and we encountered countless stinging insects and plants. Despite how well prepared we were, we experienced punctures, engine overheating problems, impaled radiator hoses and instances when bolts rattled themselves loose or were lost completely. Thankfully, Leon was a skilled bush mechanic who kept the ATVs going with minimal tools.

Dion and Amos stopped regularly to interpret the landscape for us, pointing out medicinal plants and bush food species. They recognised that after years of not being accessed, the grasslands and forest understoreys were very overgrown, and the land was out of balance. Therefore, as we went, they ignited small spot fires to reduce the vegetation. They had been taught these important landscape burning skills by their forebears. Looking behind us, I often saw plumes of grey smoke rising skywards. In a few days time, on our way back, I would get to see the benefits of these fires.

Our campsite that night was in a wide sandy riverbed at Attack Creek, named for an Aboriginal attack on explorer and state geologist Robert Logan Jack in 1879 as he and his team searched for new goldfields throughout Cape York Peninsula. We were now officially entering the brothers’ grandfather’s Country, Ngaachi Kaantju. Dion conducted a ceremony to let the spirits and ancestors of the land know we were travelling here, that we were friends and not foe, and to ask for protection during our journey. During the ceremony, Dion passed his smell – a smell that was passed to him from his ancestors, through the generations along his lineage – to us by rubbing his hands under his arms and then onto our hair and bodies. In doing so, he signified that we were of him, and welcomed us to his people’s Country. Each one of us underwent this ancient practice in silence under the gaze of the tall rainforest trees that lined the riverbanks. Being welcomed in such an intimate way was truly humbling.

The river here was merely a trickle, but it was clear from the width of the riverbed and the presence of a big fallen tree near our campsite that would have been deposited by a previous torrent, that this would be a major river during the wet season. The trees were enormous, and the vegetation was completely different from what we’d seen during the day as we traversed vast swathes of sparse arid zone.

After setting up camp, we headed off with Dion and Amos in the hope of finding a cuscus, palm cockatoo or green tree python, with no luck. We recorded multiple frog calls to submit to the Australian Museum FrogID app and revelled in the beauty of the place.

As we returned to camp we came across four dingoes in the riverbed. The two smaller ones turned and ran as soon

as we locked eyes, but the two larger ones stood long enough for us to take a picture. As the sun set and we bathed our weary bodies in the warm light of the campfire, a universe of stars began to emerge between the outstretched limbs of the canopy above. A night of storytelling and camaraderie unfolded.

Attack Creek proved a challenge for our ATVs. Mine developed a potentially serious oil leak and Darrock’s starter motor misbehaved. Leon was able to keep the vehicles going using skill, a few random items we had at hand, and some luck. We were confident enough to continue our push to the coast, so broke camp and hit the track for another full day of riding, with about 60km to cover.

The landscape pattern from the day before repeated. Large expanses of open bushland were interspersed with low-lying rivers or creeks, and steep rainforest climbs and descents. It all made for adventurous riding, and as we moved closer to the coast, we felt more and more isolated.

About 20km in, Dion and the rangers bid us farewell to return to business back in Coen. We wouldn’t have made it this far without them. From here on in, it would be just us and Amos.

Amos’s excitement grew as he reminisced about his last trip to his favourite spot on the beach we were headed to. He told us of a pristine coastline with an endless bounty of huge mud crabs and blacklip rock oysters, where crocodiles as long as mini-vans patrol estuaries teeming with fish.

We finally hit the soft sands of the beach in darkness after 11 hard hours on the track. We would have to wait until morning to see its full glory. Amos selected a camp away from the water’s edge and lit one last spot fire in the coastal scrub to thin out the undergrowth, scare away snakes and deter curious crocodiles. Exhausted, we clumsily made camp, ate a simple meal, fell into our tents, and drifted off to sleep.

Dawn revealed a sprawling, deserted, windswept beach that stretched as far as the eye could see in either direction. Amos suggested we fish the river mouth just to the north where, when the tide is at its lowest, you can harvest oysters the size of your hand and spear mud crabs.

Upstream, both banks of the river were lined with thick mangroves. Amos ventured straight into the knee-deep water, spear and fishing lines in hand, unconcerned by the sight of freshly made crocodile slides along the muddy banks. In no time at all, we caught a barramundi and a mangrove jack, no surprise given we could see so many in the water. Amos lit a fire and cooked the fish atop the embers. They were delicious, probably even more so because of the setting. We were on Country, with a Traditional Owner, eating fish straight off the fire, just as Amos’s ancestors had done in that exact spot for thousands of years.

Next, Amos pointed his spear to a low rocky outcrop about 100m off the shoreline. “Careful of stonefish,” he warned as we followed him through the ankle-deep water. The outcrop glistened with hundreds of blacklip rock oysters. Using the blunt side of an axe, we shucked them and ate our fill right there.

We felt decadent consuming such fresh and sought-after seafood in this beautiful place, but it didn’t stop there. Amos soon took off into knee-deep water, yelling “mud crabs!” Using his spear, he harpooned three in as many minutes and put them in his bag. Back to the fire we went, and before we knew it, the green mud crabs had turned a glowing red and were ready to eat.

The rest of our day was spent exploring the remote beach. It was about 6km long, with an impassable river mouth at its northern end and a rocky headland at its southern end. Offshore was the far northern section of the Great Barrier Reef, and to the west was the mighty McIlwraith Range.

Amos knows this beach like the back of his hand. During our time here, we visited several of his favourite fishing spots. He also took us to permanent freshwater springs of great cultural significance, and to some of his grandfather’s old campsites, where he fondly reminisced about being a young boy playing with his brother, Dion. The beach quickly gained a special place in our hearts too, for many reasons but none more than being here with Amos.

On our last night there, sitting by a crackling fire with bellies full of fresh seafood, we got to experience, for a short while anyway, life in rhythm and harmony with nature – living off, and with, the land. It’s a way of life that First Nations people have always known. It was through the generosity of Amos and Dion, and their willingness to share their Country with us, that we got to enjoy this life-changing, unique immersion in the mighty McIlwraith.

Dean Miller and his team thank Can-Am, Anchorline, Macpac, Pelican, Uniden, Aussie Powersports, Warn Winches, Duncan Powersports, FATMAP, Kimberley2Cape, Tyrepower Cairns, Tackle World Cairns, River Bend Canvas and Urban Wheelz for products and support to make this expedition possible.