I curse, slamming my car door as I step out into the frigid Snowy Mountains air. “What? It’s gone!” I’ve just driven two hours on teeth-rattling back roads from Canberra to photograph Adaminaby’s Big Trout.

Weighing in at 2.5 tonnes and measuring 10m in height, it’s not only one of Australia’s better-known “Big Things” (BTs), it also holds the lofty title of the world’s biggest trout.

However, where the colourful rainbow trout – which has welcomed shivering visitors to the village’s main street for the past four decades – should be, there is instead a metal tower, draped in blue plastic, which is billowing in the stiff southerly. It’s also ringed by metal fencing. But for a lack of police tape, you could be excused for thinking it was a crime scene.

Has Adaminaby’s pride and joy been trout-napped? Surely not.

Where would you hide a fish that big? Maybe she just got sick of camera-toting tourists jumping on her tail and she wriggled her way to one of the nearby streams laden with her (much smaller) namesakes?

“Perhaps you should have checked out the Big Banana [in northern New South Wales] instead,” quips my wife, still in the passenger seat. “It sure would have been warmer,” she adds, before hastily closing the window.

Suddenly, a movement near the top of the scaffolding catches my eye. A man peeks out, clad in overalls, beanie pulled low over his ears and paintbrush in hand. “Can I help you?” he asks, while trying to remove a safety mask from his face. It’s Mark Burns from Cooma Crash Repairs, who, along with workmate Chris McCullough, is undertaking “urgent repairs” to Adaminaby’s fabled big fish. Stopping for an early smoko, the pair generously invite me inside for a peek.

“If we didn’t start work on her, she probably would have collapsed,” Chris says guiding me through the trout’s more delicate regions, then up a rickety ladder to her snout. “She had a pretty bad diagnosis,” Mark adds. “If you think she looks bad now, you should’ve seen her when we started work on her six weeks ago. She had everything from fin rot to gangrene.” Oh dear. The panelbeaters/trout whisperers show me where they’ve filled cracks and fixed fractures with a special poly-compound made for extreme weather conditions. It’s meticulous work. And yes, they let me take a photo. It’s not the iconic exterior shot I was after, but even better: a close-up of her freshly reconstructed eyeball, ready for repainting. Before this intimate encounter 10 years ago, the Big Trout was just another 3D billboard erected to lure travellers off the highway and spend a few dollars in fledgling businesses. Becoming entangled in her entrails, and seeing dedicated locals risking frostbite to maintain her, changed all that. I was…hooked.

My wife still laments, “You don’t even like fishing!” when, on each trip to the snowfields, we make a lengthy detour to make “yet another pilgrimage” to the Big Trout. It’s funny how you can get attached to an oversized fibreglass fish.

As with many other BTs, Australia has multiple Big Trouts. One is in Oberon, 340km north of Adaminaby, where, while recently at the front bar of The Royal Hotel, I suggested to a barfly that his town’s Big Trout didn’t stack up to the one in Adaminaby.

It was a genuine attempt at friendly chit-chat but I may as well have maligned his mother’s character on national television. To my wife’s disdain, it almost ended in fisticuffs, and even shouting a round of drinks didn’t placate him. It turns out I’m not the only victim of a spirited tirade from a parochial local sticking up for their town’s claim to fame. “People can get really protective and territorial about their BTs,” says Dr Amy Clarke, a senior lecturer in history at the University of the Sunshine Coast. And if anyone should know, it’s Amy. She specialises in built heritage and material cultures and has earned the enviable moniker of Australia’s “BT expert”.

“A few years ago, during a talkback segment on ABC Radio, I was labelled “un-Australian” because I refused to call the Big Uluru [which burnt down in 2018], at Leyland Brothers World at North Arm Cove near Newcastle, a BT,” Amy explains. “Because it wasn’t bigger than the rock it was imitating, actually only 1/40th the size, it clearly couldn’t be classified as a Big Thing.

“I thought my statement was uncontentious, but it received an irate response from some listeners who promptly called the station, including one furious local who roared ‘How dare you!’ down the phone line.” Unlike my piscatorial face-off in Oberon, which compared two similar BTs, in Amy’s case it was about definition.

If there was a competition for the Big Things that most closely resemble their real-life namesakes, the koala at Dadswells Bridge, in western VIC, would be a top contender.

To her, the object must satisfy four key criteria: “It must be human-made, three-dimensional, located outdoors and be obviously bigger than the real-world thing it is imitating.” Surely it also needs to be beside a highway as well. “No. Roads move, so I don’t include that as a criterion,” she says.

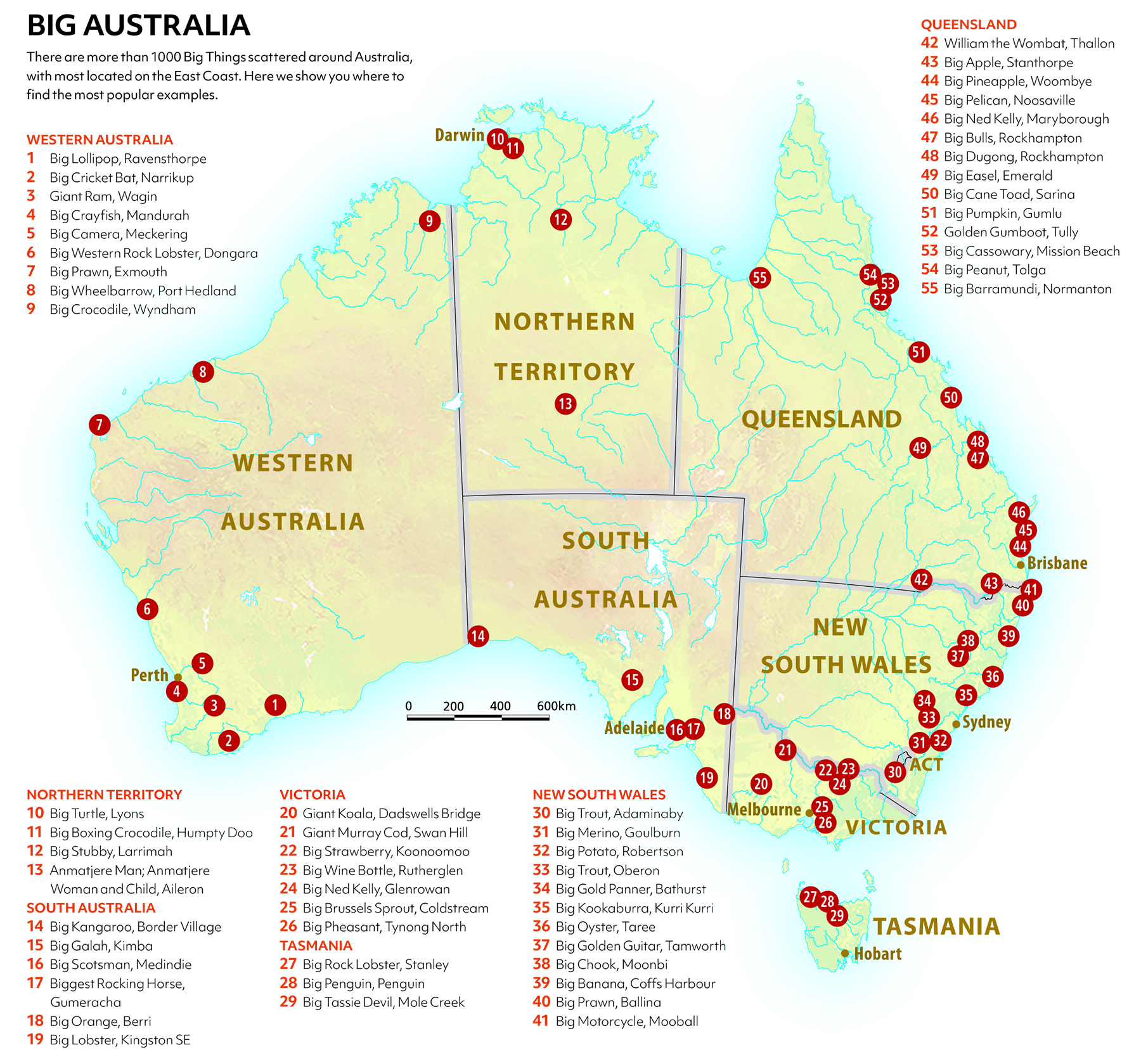

So, how many BTs are dotted around our country? According to Amy’s broad definition, “At last count, there were 1075.” Yes, that many, but that number includes commissioned works of public art, which Amy says inflates the total by about 25 per cent.

“People interested in BTs reflect the full spectrum of society, not just art historians and academics, so debating what is and isn’t a BT is a great way for people to have conversations about heritage,” she says, adding, “Many of them may be ‘lowbrow’, but they also hold a deeply personal resonance with the people who have lived near them, and visited them.”

Although many artists and builders have dabbled in the creation of BTs, there are a handful of entrepreneurs who can boast multiple BTs on their resume. These include brothers Attila and Louis Mokany, who were responsible for three of arguably our nation’s most eye-catching roadside sculptures. First up, in 1985, to encourage motorists to stop at their Goulburn service station and restaurant, and as a less than subtle nod to the area’s fine-wool industry, the Mokanys cobbled together the 15.2 x 18m Big Merino. That’s seriously big – no-one could argue it’s not bigger than the animal it’s imitating! Buoyed by the success of Rambo, as the anatomically correct (and well-endowed) ram was soon named, next off the production line was the Big Prawn at Ballina in 1989, then the Big Oyster at Taree the following year. Much to their disappointment, the Mokanys’ subsequent proposal in Albury for a Big Murray Grey, a breed of cattle, didn’t get the green light.

Although the Big Oyster has seen better days (it’s now part of a new car dealership), Rambo and the oddly nickname-less Big Prawn continue to entice travellers for that must-have selfie, even though they’re no longer bolted to their original locations.

In 2006, 14 years after the Hume Highway bypassed Goulburn, Rambo got itchy feet. Under police escort, and the watchful gaze of an entire town, the 100t (yes, a leading contender for our heaviest BT) ram was hauled to its current home on the new highway. Rambo’s owners, who’d lost more than 40 busloads of tourists a day after the bypass opened, weren’t the only winners in the move. A handful of residents who were often the, er, butt of many jokes, having lived with uninterrupted views of the concrete ram’s huge backside for many years, were also cheering.

Standing more than 17m tall, Kingston SE’s Larry the Big Lobster, in SA, is one of Australia’s biggest and most conspicuously kitsch Big Things.

While Rambo was a hit with Goulburnites from day one, the much more conspicuous prawn, resplendent in bright orange paint, was viewed by its many critics as nothing more than a bad smell. The fact it was minus a critical part of its anatomy – its tail – probably didn’t help. “When it was first erected, lots of locals opposed it, but in 2010, after the service station it was attached to was approved for demolition, supporters came out of the woodwork,” Amy says. “Residents essentially stormed the council chambers, pleading for their prawn to be saved.” Eventually Ballina’s Bunnings came to the rescue, and the previously condemned crustacean now stands sentinel over the hardware store’s fundraising barbecues, no doubt hoping no-one hollers, “Throw another shrimp on the barbie!” Oh, and yes, they even added a tail.

The gong for the most-moved BT is safely stashed in the pouch of Matilda, the 13m-tall kangaroo who, after her stint as the 1982 Brisbane Commonwealth Games mascot, retired to a Gold Coast water theme park. When that site was redeveloped, she hopped 200km up the M1 to a truck stop in Kybong, near Gympie. Today, she stands outside another petrol station, at neighbouring Traveston. Even though Matilda can no longer wink or wiggle her ears with the grace she once did on the big stage, there’s no mistaking she’s a giant kangaroo. The same cannot be said for all BTs.

Taking up a whole block in the main street of the sleepy NSW Southern Highlands village of Robertson, where farmers have been growing famous red-soil potatoes for years, is – you guessed it – a big spud. Unless you’ve seen it yourself, you’d wonder why the terrific tater is so maligned.

Here’s a clue. Since it was unveiled in 1977, not one single highlander has referred to the 10m-long, 4m-high tuber by its official name, preferring instead to call it the, ahem, Big Poo-tato. I’m sure you get my drift.

Amy is sorry for the spud: “I like things people have genuinely set out to do and unfortunately in this case it didn’t quite translate into reality. I actually think it’s quite beautiful. There’s even been talk of it being heritage-listed, like Queensland’s Big Pineapple.”

When her parents bought the much-mocked giant vegetable in 2014, “to stop developers moving in and turning it into a supermarket”, celebrated Sydney playwright Melanie Tait enthusiastically and bravely adopted the title of the “Big Potato Heiress”. Despite having to endure eight years of unwanted puns directed her way, when Melanie discovered in late 2022 that her family was selling up, she felt obliged to pen an article for The Guardian.

“Generations have grown up with it as a landmark and sign of stability in a place that’s forever changing,” she reflected, before expressing hope that “the new owners realise how special this construction of cement and soil is”. Aww.

the local park.

At the opposite end in the popularity stakes is Larry the Big Lobster, in Kingston SE, South Australia. Persistent rumours suggest Paul Kelly, the artist who built the 17m-tall spiny lobster, misunderstood the plans and laid out Larry in metres instead of feet – hence his leviathan size. Paul dismisses the claims as scurrilous. The gigantic steel-and-fibreglass lobster regularly wins polls as Australia’s favourite BT, so if Larry’s measurements were an oversight, it was probably a blessing in disguise. “No-one wants a small Big Thing,” Amy jokes.

As one of the biggest BTs, if you wanted to pilfer Larry, you’d need an army of angle grinder–wielding assailants and a semitrailer fleet. There’s a parade of other, easier to transport BTs that have mysteriously gone missing in the night. These include Bowen’s much-loved Big Mango, which disappeared from its pedestal on the side of the busy Bruce Highway on a hot summer night in February 2014. Search parties led by miffed mango munchers scouted all roads in and out of the north Queensland town. But they needn’t have worried. The 10m-tall missing mango was soon located, partially hidden under a tarpaulin in nearby bushland. A chicken restaurant chain had temporarily fruit-napped it as a publicity stunt for a new menu item. Really.

Then there’s the case of the oversized fibreglass bull that stood for many years outside a butcher’s shop in Bangalow in northern NSW before vanishing – but not without trace. After it was filched, owner John Herne received reports from eyewitnesses who spotted the big bull at numerous locations, including a beach at Port Macquarie and grazing outside a service station near Newcastle. It was also spotted at the Big Prawn in Ballina, prompting speculation of a BT meet-up. When John received a photograph in the mail of the missing bull alone in a paddock at an unknown location and plastered in psychedelic-coloured dots, it almost sent him over the edge.

The broken-hearted butcher was only reunited with his prized bull when, after an anonymous tip-off, he enlisted the help of a vigilante bunch of Bangalow tradies who tracked down the bull in a paddock between Casino and Tenterfield.

“When he went missing, he weighed 682kg, but on his return he was less than 600kg,” John says. “He was sporting a large gash on his side and was minus his ears – he must have put up a good fight.”

About 800km north, in Rockhampton, half-a-dozen big bullocks celebrate that city’s status as Australia’s beef capital and perhaps wouldn’t mind having an ear nicked, instead of their testes, which have been an irresistible target for pranksters. A cabinet-maker by trade, Chris Murphy worked as a slasher driver and an artificial insemination technician for cattle, before the mid-1990s, when he joined the Rockhampton Regional Council and volunteered to look after the bulls. Since then, he’s carefully crafted dozens of replacement testes – each weighing about 5kg – using a special concrete mould. “I’ve even invented a new way to attach them to the bulls using a metal rod that makes them harder to steal,” he proclaims. Tony Williams, Rockhampton Region mayor, is just as proud: “Our bull statues are iconic. Often if there’s one thing a person knows about Rockhampton, it’s the pride of place our bull statues hold at the entry points to our city.”

While the heritage-listed Big Pineapple at Woombye in QLD (left) grabs all the headlines, there are several spiky spin-offs, including the much more modestly proportioned fruit at Ballina, NSW (right).

There must be something in the water in Queensland because, no matter how you define a BT, the Sunshine State is indisputably “Australia’s BT capital”. It has all manner of oversized fruit, vegetables and animals, and the Bruce Highway is littered with quirky BTs, including Tully’s 7.9m-tall Big Gumboot (officially the Golden Gumboot). Tully, the state’s wettest town, receives an average annual rainfall of more than 4m, and it holds the national record for the most rain in a year – 7933mm, in 1950. Lucky the concrete gumboot has drains in the bottom or it would fill up.

Meanwhile, Western Australia fails to pull its weight in the BTs stakes. Among its best-known BTs are the Big Western Rock Lobster at Dongara, a Big Prawn in Exmouth that’s small fry compared with Ballina’s colossal crustacean, and a somewhat incongruous Big Lollipop at Ravensthorpe. Apparently, it’s the world’s biggest free-standing lollipop. Sure, it’s propped up outside a sweet shop, but sugar on a stick is hardly synonymous with this far-flung town. But the 8m-tall aluminium-and-steel lollipop is nowhere near as out of place as the Big Ned Kelly in Maryborough, Queensland, where it blatantly promotes a hotel. Ned, who never ventured within cooee of Queensland, would be turning in his grave. If you must eyeball a more appropriately positioned Big Ned, then beat a path to Kelly heartland in Glenrowan, Victoria, the location of the infamous bushranger’s last stand, where a 6m-tall Ned, clad in iconic armour fashioned from old farm ploughs, bails up visitors to town.

Back in WA, and hardly worth a detour to see, you can pour acid on the Big Periodic Table plastered on a wall of a science faculty building at Edith Cowan University. The same goes for the World’s Tallest Bin in Kalgoorlie. What rubbish. It’s a pity there’s not a bigger bin to toss it into. WA is also home to one of the strangest BTs – the Big Camera, built into the facade of a former service station/camera museum at Meckering, 135km east of Perth. Of course, beauty is in the eye of the beholder, and as more BTs pop up along our highways, there will always be debate as to how they compare with the existing stock of BTs.

Amy Clarke reports, during the past decade or so, we’ve been enjoying a renaissance in BTs. “New ones are being unveiled at a much faster rate than those being demolished,” she says. This is good news for BT afficionados because it means there are even more to visit, even for Amy (who has seen more than most).

“When my brother recently got married, I drove past the Big Apple in Stanthorpe for the first time, as well as some other new BTs in northern NSW,” Amy says. “I confessed to my brother, I was way more excited taking photos of all of them than attending his wedding… He was none too impressed.”

I’ll bet. A feeling I’m sure my wife can relate to.

Mint recognition

The Big Oyster at Taree didn’t make the cut, nor did Robertson’s Big Potato – possibly for obvious reasons – but Swan Hill’s Giant Murray Cod did, twice. So did the Big Lobster at Kingston SE in SA.

If you’re a stamp or coin collector and a fan of Australian Big Things, then your passion has been catered for three times since 2007. That was when Australia Post issued its first collection of BTs, five 50c stamps with distinctive illustrations by renowned artist Reg Mombassa. A further set of five, of $1.20 denomination, was issued in September 2023, illustrated this time by Nigel Buchanan.

A set of $1 uncirculated coins was released earlier in 2023 by the Royal Australian Mint. Uncirculated coins are created just for collectors, as the name suggests, so you aren’t likely to get a Wak Wak Big Jumping Crocodile in your change at the servo, more’s the pity.

According to Australia Post, stamp designs must appeal to more than a narrow section of the community – in fact, they must be of “outstanding national or international interest” and not be likely to cause “public divisiveness”. So don’t be drawn into an argument over whether Canberra’s Big Swoop magpie is more likely to have a nip than Muswellbrook’s Blue Heeler, or you might cop the rough end of a Big Pineapple.

Photographer Trent Mitchell‘s book Australian Lustre will be launched later this year.

RELATED STORY: Australia is littered with aging super-sized statues