Capturing despair

Images of the chaos and damage wreaked on Darwin, capital of the Northern Territory, by Cyclone Tracy on Christmas Day 1974 are common and widely published – shattered houses, crumpled aircraft, buckled power poles and ships aground. But this one was particularly poignant.

What was once a thriving capital city was devastated between Christmas Eve and the following morning, with the lives of more than 45,000 residents radically changed forever by the disaster. Media played a major role in helping both the authorities and the public realise the extent of the destruction that Darwin had suffered.

Footage captured that morning for ABC TV by freelance cameraman Keith Bushnell was flown to Brisbane on an RAAF Hercules and aired nationally that night, bringing the magnitude of the disaster to the consciousness of all Australians. Until then, those receiving the earliest reports of conditions in Darwin could not comprehend what had actually taken place. Surely it hadn’t been wiped out? That wasn’t possible. They were wrong.

Within days, disaster relief was organised, evacuations commenced, and the massive task of cleaning up and rebuilding Australia’s most northerly city began in earnest. Communities across the globe were shocked and saddened at the scenes that were being printed in newspapers and broadcast into their living rooms. What could they do to help? The Darwin Appeal was launched and money began to pour in from around the world – donors hoping to assist in some small way those who had experienced the tragedy that had befallen them.

Media companies sent journalists and photographers to Darwin any way they could, most hitching rides with defence and civilian flights heading north for the relief effort. On Boxing Day, carrying his camera gear and little else, The Australian Women’s Weekly staff photographer Keith Barlow scored the last seat on a navy aircraft. He spent the next few weeks in Darwin and it had a profound effect on him.

“The horror of disaster is everywhere,” he said at the time. “I wish it were possible to lock the room and close off the scene for a few hours. But there is not a room left in Darwin with such privacy, such luxury.” Keith’s colour images captured not only the stark reality of a destroyed Darwin, but also the human side of the disaster.

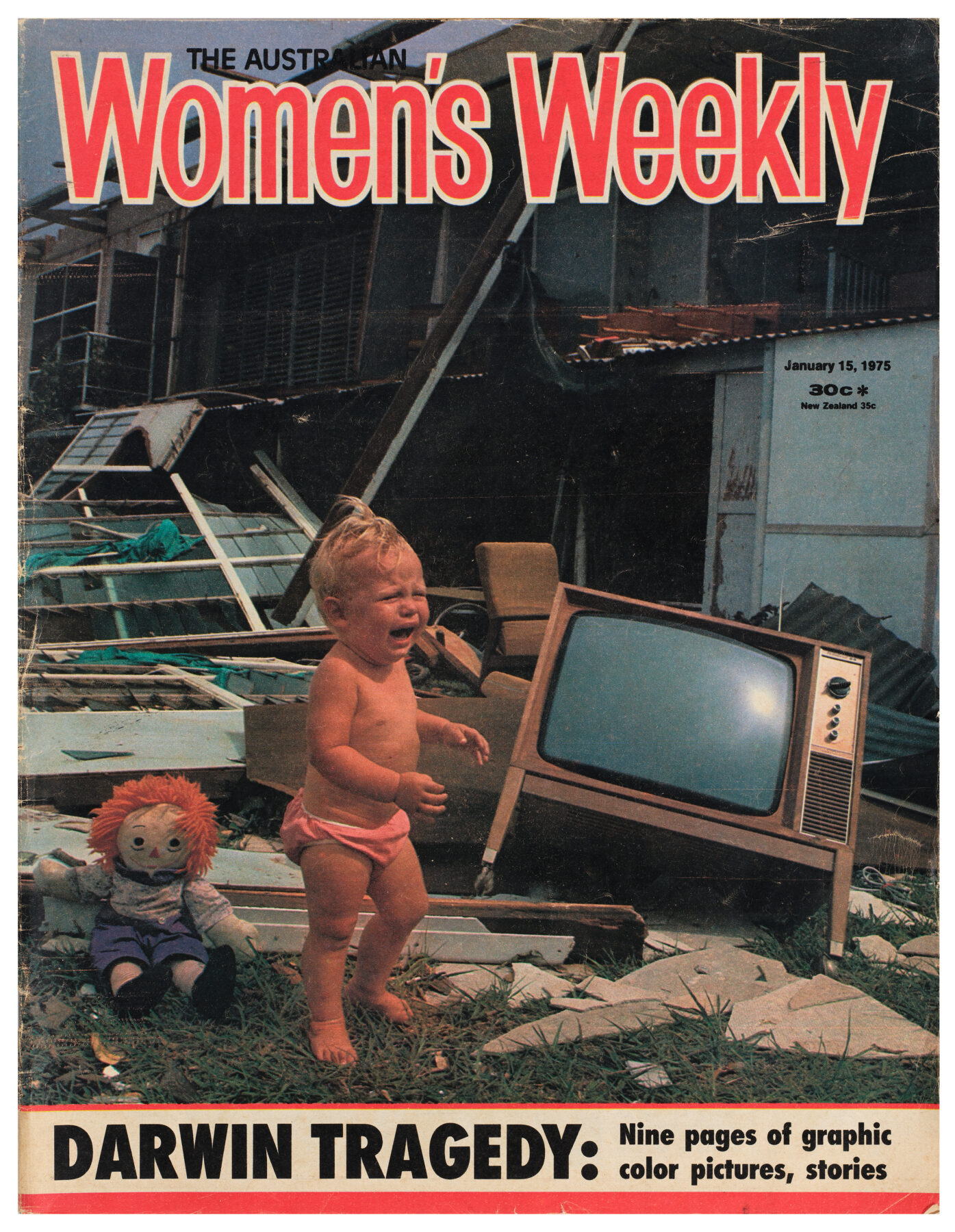

His best-known image – “my proudest photograph”, he later wrote – was used for the cover of The Australian Women’s Weekly on 15 January 1975. Featuring a crying blond toddler in cloth pilchers near a broken television and a Raggedy Andy doll, all in a yard full of building debris with a shattered house in the background, this single image perhaps did more than any other to turn the hearts of the people of Australia to the survivors of Darwin. It tugs at the heartstrings in a way most images cannot. But how did he manage to get this shot?

Tansy Jones, seven years old at the time and the owner of the Raggedy Andy doll, was a sister of Gavin, the boy in the photo. Her family lived in a classic Darwin elevated home at 8 Elsey Street in the suburb of Parap. Her family (Dad, Spike; Mum, Margaret; Aunt Mollie; older sister, Hesta; and younger brother, Gavin) sheltered from the cyclone in Aunt Mollie’s ground-level flat and survived.

Tansy remembers the day Keith Barlow turned up: “One day a man came into our yard; he was a freelance photographer. He told Mum he had noticed her sign at the front of our house. My mum has always had a dry sense of humour and at the time Winfield cigarette adverts stated ‘Anyhow, have a Winfield’. Mum had written in chalk ‘Anyhow, Happy New Year’ and had managed to find some of our Christmas decorations and decorated the sign.

“[The photographer] said he was on his way to have his tetanus shot because all residents had been advised to get one. He asked if he could photograph the sign and [Mum] said yes. First, he took a photo of us next to the sign. We all smiled as you would normally do for a photo and he said, ‘No, no, no, you have just lost your home, you need to look sad,’ so we all put on a sad face. He then wanted a photo of my brother in front of the fallen wall. My brother was upset at being put down on the ground and started to cry. The photographer told me to give him my doll and I told him that I wouldn’t because it was my doll. He insisted, and I handed over my doll, but my brother still cried.”

And that was how this iconic picture was captured – an upset 15-month-old Gavin Jones surrounded by the wreckage of his home, with his sister’s doll nearby.

After loving and keeping safe her Raggedy Andy doll for almost half a century, Tansy has donated it to the Museum and Art Gallery of the Northern Territory. It will go on display in the refreshed Cyclone Tracy Gallery in December this year.

Jared Archibald OAM is Curator of Territory History at the Museum and Art Gallery of the Northern Territory and has been involved for many years in the gathering of oral histories and memorabilia from survivors of Cyclone Tracy. As part of the 50th anniversary commemorations for the tragedy, the Museum will reopen its interactive Cyclone Tracy Exhibition on 7 December 2024.

The November–December issue of Australian Geographic will also feature an extensive article –

with which Jared and other musuem staff have been involved – about Cyclone Tracy and its impact on Darwin