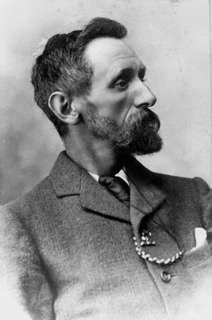

The splendidly named Basil de Burgh Newth was part of a small group of mainly young men who, at the end of the 19th century, lived year-round on mainland Australia’s highest point – Mt Kosciuszko, in New South Wales, where a weather station had been established by colourful meteorologist Clement Wragge. From 1897 to 1902 the group sent regular weather records to Wragge and the experience remained with Newth for life – he spent 27 months at the top of Australia, but was still writing about it 50 years later, saying he was “well repaid in interest, experience and adventure… One could write a book about it all.”

Born in England, Wragge was dynamic and unconventional and, in 1881, he established a weather observatory on Britain’s highest peak, Ben Nevis, on behalf of the Scottish Meteorological Society. He also established a comparative sea-level station at Fort William nearby. The principle of this work was that forecasts could be aided by making and comparing ‘upper’ atmosphere studies (through simultaneous readings of instruments) with the findings of the sea-level station. British scientists welcomed the results and Wragge was awarded a gold medal by the Society.

Wragge then came to Australia and, in 1887, he became Queensland’s Government Meteorologist, establishing a network of weather stations and publishing Australia-wide forecasts. He furthered the study of tropical cyclones and began the practice of naming them, as we do today.

Wragge wasn’t a typical Victorian-era man. Vegetarian, interested in eastern religions, with green environmental views, he stood out from a 19th-century crowd. This lack of orthodoxy, plus his outspokenness and lack of tact, often put him at odds with his intercolonial peers.

Wragge got to work on high-level/sea-level observatories in South Australia and Tasmania and then announced his intent to build a station on Mt Kosciuszko. In the context of his times, many decades before weather balloons or satellites, his ideas were sensible. He was well regarded by overseas peers but was criticised by his intercolonial contemporaries. Wragge’s Mt Kosciuszko project required the summit station, plus a coastal station at Merimbula, and was privately sponsored.

In December 1897 Wragge set out for Mt Kosciuszko, taking tents and instruments. With him was Charles Kerry, a well-known Sydney photographer and Snowy Mountains publicist who’d led the first winter ascent of Mt Kosciuszko only four months before – his Kiandra ski photos are famous. Mountain stockman James Spencer acted as their guide.

Mad place to live

Despite it being summer, the expeditioners arrived at the summit in freezing conditions. One of the Queenslanders went to bed one night wearing no less than 29 items of clothing!

By 10 December the tent-based weather station was up and running and an assortment of weather instruments was operating from atop Mt Kosciuszko to take regular readings of air pressure, temperature, humidity, wind, cloud mass, precipitation and surface ozone. The next day, Wragge left the summit for Merimbula, and for the next five years he directed both stations from Queensland. At Mt Kosciuszko the observatory was run by his team (at times including Wragge’s sons) who pursued their science in one of Australia’s harshest and most isolated environments.

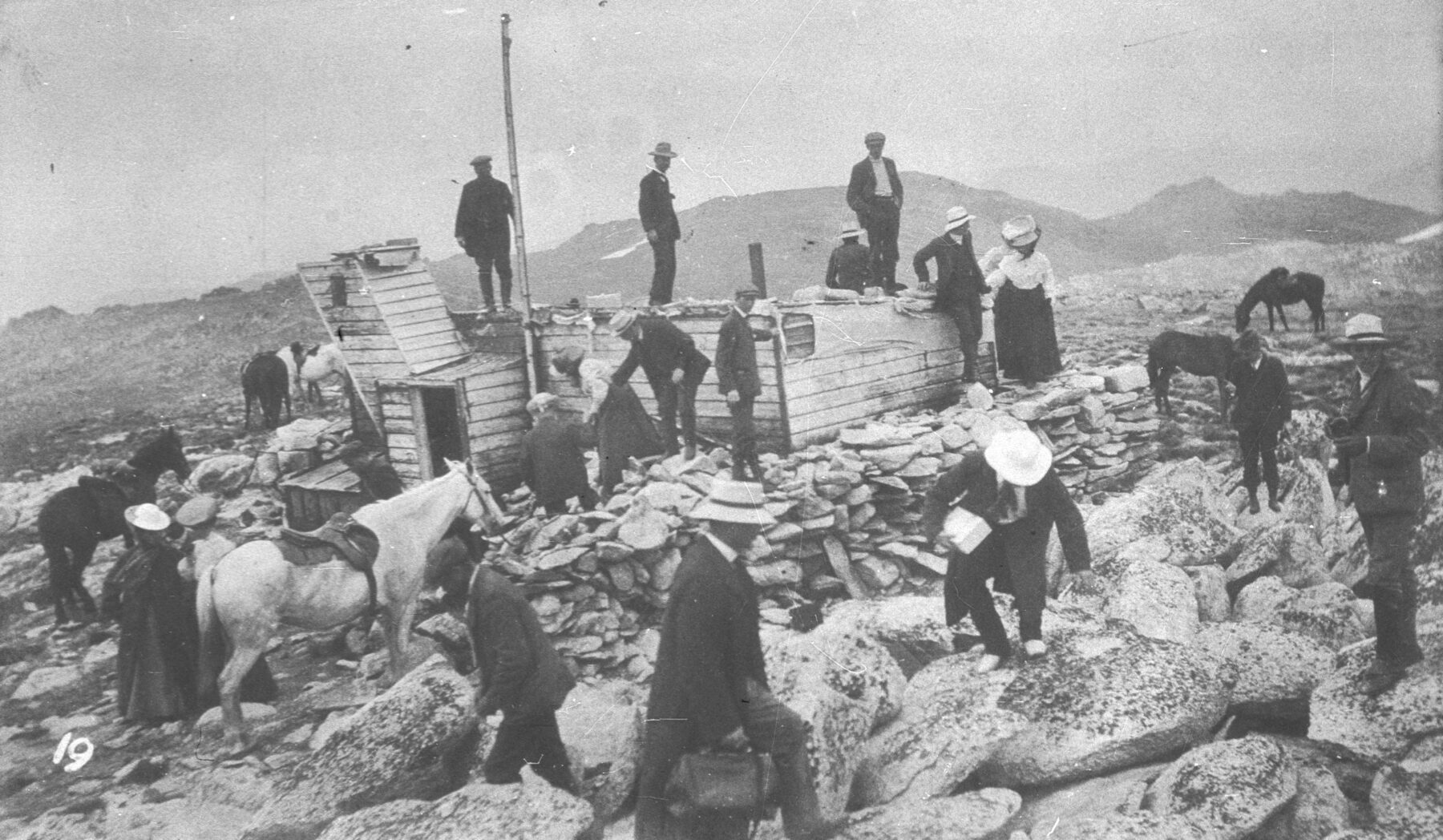

The tent observatory stood for only two months. In February 1898 a terrible storm hit Mt Kosciuszko and 160km/h winds shredded the tents. The three observers abandoned the summit and retreated to Jindabyne, lucky to survive. Clearly, if the observatory was to continue, the NSW government would have to fund a permanent building. Premier George Reid obliged and Wragge was elated.

By April 1898 a hut had been constructed. Built by two Cooma builders, brothers Arthur and Herb Mawson, and their partner, D. McArthur, the simple weatherboard structure had a number of adaptations for the severe summit weather, including 2.5cm-thick storm glass in the windows. Outside, boulders were piled against the walls to prevent the hut being blown away.

Despite the fears of locals who thought it madness to try to live on Mt Kosciuszko in winter (one local wit presented Newth with a coffin catalogue!), observers Newth, Bernard Ingleby and Harald Ingemann Jensen saw out the season.

That experience led the men to adapt the building. The hut’s door was often snowed under, so they built an enclosed stairway with a hatch at the top, providing roof-level access. Although no sign of the observatory exists today, this form of access can still be seen at Cootapatamba Hut, built for the Snowy Mountains Hydro-electric Scheme in the 1950s.

Wragge ordered a 24-hour schedule of instrument readings that dictated the routine of the observers. The schedule was no easy task, particularly during night-time blizzards. An evocative description of a midnight winter reading was documented by one of Wragge’s sons, Clement Lionel ‘Egerton’ Wragge.

The rostered observer, wrote Egerton, was woken by an alarm clock. He left his sleeping bag, dressed and placed a lamp near the window to guide him back to the hut through the dense cloud outside. He then climbed the stairway and opened the hatch, “…which is no easy matter under the circumstances. Waiting for a slight lull in the fury of the tempest, he exerts all his strength to force it open, while the wind is trying to force it down on his head… As the fury of the blast strikes him, he is seen to stagger, and is almost blown to the ground… Breathing is difficult, and it is necessary to place the hand over the mouth in order to do so. Snow and sleet driving across the mountain at a furious rate almost blinds him, and cuts his face. The light from the lamp at the window is thrown in a great yellow streak out against the fog bank.”

The rostered observer reaches the thermometer screen and reads the instruments. All the while he’s trying to ignore the fine snow “that has found its way down his neck and over his gum boots”. The observer hastens back to the hut: “As he goes, the light from the lantern perhaps flashes on a [ski-] brake-pole stuck in the snow, now covered with long white icicles, standing like some ghastly spectre against the fog. The sudden sight of this chills his blood, and floods the mind with a dread of the supernatural, and he makes a bound for the hatch. In his hurry to get into the hut he slips on the steps covered with ice, and goes tumbling to the bottom, cursing meteorology and meteorological instruments in general. This performance must be repeated again at 4am, and although unpleasant at the time, is extremely fascinating.”

Given that it was hard even for drays to get to Mt Kosciuszko in summer, and wheeled transport anywhere into the mountains west of Jindabyne was difficult, the observers were living in a very isolated part of the country.

Amazingly they maintained the winter link to Jindabyne. Every few weeks they skied over the alpine plateau, descended to the Thredbo River valley, rode to Jindabyne, posted data to Wragge and purchased provisions.

Newth, a Candelo clergyman’s son, was the first to make this winter journey solo and is a hero of the Wragge story. In 1899 Newth and Rupert Wragge saved the life of Rupert’s 19-year-old brother, Egerton, when he became hopelessly lost during a trip from the town, surviving hypothermia.

A place of natural beauty

Nature’s wonder and beauty, however, made up for the privations. Ingleby wrote of a fine winter’s day: “Away to the north-east and south-west…were mountains rising tier upon tier, clad from base to apex in a mantle of purest white.”

Natural phenomena were legion. They witnessed St Elmo’s Fire – natural luminous electrical discharges – with Jensen recalling how Newth took a crosscut saw outside and “each tooth of it became a living flame”. They also experienced a Brocken spectre, in which the men’s shadows were projected onto cloud and surrounded by prismatic colours.

Much of the men’s winter leisure time was spent on skis (known as snow-shoes at the time). Jensen wrote that as soon as a fine day arrived, “We donned our snow-glasses, fur caps and snow-shoes and raced wildly down the mountain side like dogs let loose from the chain. Sometimes, when the moon was bright, we would indulge in this sport by night.”

The observers raced to Lake Cootapatamba, and built ski jumps. They made the first ski trips to mainland Australia’s second-highest peak, Mt Townsend, and to Blue Lake, with the station’s two dogs, Zoroaster and Buddha, trailing through the snow. The observers mounted a sail on the station’s sled. Their winter activities were captured by intrepid Wagga photographer Donald McRae, who climbed Mt Kosciuszko in 1899 carrying his heavy glass-plate camera.

But with funding short and little published data, scepticism increased. Some of the observatory information was supplied to British and German Antarctic expeditions, though with no telegraph or telephone link between Mt Kosciuszko and Merimbula and no speedy transmission of data, any forecasting ability was crippled.

In June 1902 the NSW government cut its support for Wragge’s observatory and demanded the instruments and stores be removed. It was midwinter. Egerton Wragge and two other observers struggled to get the gear down.

Remembering Wragge’s men

Only 13 years later, Egerton, serving in the 2nd Light Horse Regiment, was killed at Gallipoli and buried at sea. His name is on the Lone Pine Memorial, signifying he has no known grave. He was 34 years old.

Basil de Burgh Newth, meanwhile, had a happier career. By 1904 he’d become maths and science master at The Scots College, Sydney. He died in 1959, aged 83.

Bernard Ingleby went on to work in Sydney advertising, and associated with leaders of the Bohemian set, including Henry Lawson and the Lindsay art family. He died in 1941, aged 63.

In 1902 Clement Wragge failed in a Queensland rainmaking attempt, damaging his reputation. After the Commonwealth government assumed responsibility for monitoring weather, Queensland closed its bureau and Wragge left Australia in 1903, settling in New Zealand, where he died in 1922 at the age of 70.

Wragge’s Mt Kosciuszko project, though unsuccessful, was part of the long scientific thrust into the High Country that began in 1834 with naturalist Dr John Lhotsky – the first European to bring the Snowy River to the attention of the public. Through focusing attention on the summit area, the weather station helped open the peaks to tourism, and the Kosciuszko Road and the Hotel Kosciusko were opened by the NSW government not long after the weather station closed. There’s no memorial on the summit today, though Wragges Creek is near Smiggin Holes. The story of Wragge’s men deserves to be remembered.