Forty years ago at 8pm on 3 October 1984, Tim Macartney-Snape breathlessly picked his way onto the summit of Mt Everest. Below him was an ocean of cloud broken by darkened peaks – only his peak, the highest of them all, was still catching the last light of the setting sun.

As he waited for Greg Mortimer, so the pair would become the first Australians to climb Everest, he recorded his thoughts between ragged breaths on a tape recorder: “This is the summit of Mt Everest, Qomolangma, Mother Goddess of the Earth, the world is staggeringly beautiful from up here. In fact, it’s beyond superlatives.” Greg soon arrived in a state of total exhaustion. In the photos Tim took, Greg, clad in his red down suit, is unfurling a Buddhist prayer flag, his face a black blur in the poor light. The mountaineering cliche that “reaching the summit is only halfway” looms menacingly over the tableau like the imminent darkness.

Fifty metres below, fellow climber Andi Henderson, his frostbitten hands turning to claws, had turned around and was slowly retreating. Unable to swap his glacier glasses for prescription glasses, he was increasingly blind in the gloaming.

The hardest night of their lives was ahead of them.

A model expedition

In his book, Everest: the Ultimate Book of the Ultimate Mountain, British climber and acclaimed outdoor writer Walt Unsworth later wrote in awe about the Aussie ascent, which was achieved without bottled oxygen and in semi-alpine style. “Australia is not a nation with any great tradition of mountaineering and yet the Everest Expedition of 1984 was a model of what an expedition should be,” he observed. “Not only that, their actual achievement was astonishing; one of the greatest climbs ever done on the mountain.”

That these five Australian climbers – Tim, Greg, Andi, Lincoln Hall and Geoff Bartram – were even on the mountain was mainly due to serendipity. Back in the early 1980s it was only possible to get one permit for each side of the mountain and there was a queue, which they were not in. However, in August 1981, while Tim, Lincoln, Geoff and Andi were climbing in the Anyemaqen Range in China’s Qinghai Province, they asked their radio operator to check what permits the Chinese Mountaineering Association in Beijing had available. The answer came back: A French expedition had just cancelled their 1984 permit for the North Face of Everest.

At this stage, none of the Aussie team had climbed anything higher than 7000m. “We thought, oh shit! Tim recalls, but he and the others reasoned, “We’ve got Annapurna II [7937m] booked for 1983. This is 1984 – we should be able to have a crack.” So they booked it.

Tim and Lincoln had met while studying at the Australian National University (ANU), in Canberra, in the mid-1970s. In an article for The Weekend Australian Magazine, Lincoln said of Tim, “People are amazed when they meet him for the first time – with his Prince Charles ears and Twiggy legs – but what a lot of people don’t see, because it’s not on display, is his extraordinary drive.” Sadly, Lincoln died in 2012 of mesothelioma, a cancer caused almost exclusively by exposure to asbestos, which was traced to when, as a child, he’d helped his father build cubby houses using sheets of asbestos cement. Tim remembers Lincoln as funny and endearingly absent-minded, a powerful climber who was a great trail breaker.

Like many Australians, the pair did their mountaineering apprenticeships in New Zealand’s Southern Alps. Then in 1978 they were invited on an Australian expedition to climb Dunagiri (7066m) in the Garhwal Himalaya in India. The peak nearly ended their careers prematurely when they spent 49 hours out in the open on their summit push, including 36 hours without water. Despite their near-death encounter, Dunagiri cemented their close partnership.

Sydneysider Andi joined their 1981 expedition to Ama Dablam (6812m), which they successfully climbed via the steep and technical North Ridge. Andi had followed a similar trajectory, starting out rockclimbing, then doing a mountaineering course in New Zealand, followed by a very low-budget expedition to Changabang (6864m) in the Garhwal Himalaya. Everyone describes Andi as a very strong climber, tough and with a self-deprecating sense of humour.

Geoff, a mountain guide, joined their Anyemaqen Range trip in 1981. Well-known Australian mountaineer Will Steffen, who was also the executive director of ANU’s Climate Change Institute until his death last year from cancer, wrote in his book Himalayan Dreaming: Australian Mountaineering in the Great Ranges of Asia 1922–1990:“With scores of ascents of 6000m [Andean] peaks under his belt, Bartram was Australia’s most experienced high-altitude climber.”

The final team member was Greg Mortimer, who came along on their 1983 expedition to climb Annapurna II. Although Greg had had no previous Himalaya experience, he’d climbed extensively in New Zealand, the Andes and the European Alps. Sandy haired and slightly built, Greg was quiet but driven, and had great technical climbing skills.

Brutal preparation

In August 1983, Tim, Lincoln, Andi and Greg headed to Annapurna II, which would be a brutal but effective preparation for Everest. The summit was five vertical kilometres above Advance Base Camp (ABC), and the route required navigating avalanche-prone slopes and cliffs lined by the life-or-death lottery of glaciers calving chunks of ice and rock. One rock split Lincoln’s helmet; another broke his foot.

Before their successful summit attempt, the team spent five days storm-bound in a snow cave at 7100m. Hard, technical climbing slowed them down and they had to spend a further two nights sitting on a ledge carved out of the snow before reaching the summit. As storms raged, the following days of descent were harrowing and they were days late returning to ABC. Back in Australia it was reported that they had gone missing.

Much of 1984 was spent trying to fund their Everest expedition. At the last moment, TV station Channel Nine stepped in as the major sponsor, agreeing to make a documentary about the trip. While it brought in much needed dollars, it added extra complications and required recruiting a camera crew with the necessary climbing and filming skills.

Michael Dillon, a filmmaker who’d made several films with Sir Edmund Hillary, was recruited, along with Jim Duff, a British climber and doctor. Jim was one of the world’s most experienced expedition doctors, but he’d also worked as a sound recordist on several expeditions.

To support Mike and Jim, experienced mountaineers Colin Monteath and Howard Whelan – who later became the founding editor and publisher of Australian Geographic – were also invited. Simon Balderstone, a journalist with The Age, joined after taking a leave of absence from his job, but then convinced his employer to buy the rights to the story. Lobsang Tenzing Sherpa and Narayan Shrestha were the final two members of the expedition; their job was to provide basecamp support for the climbers.

The team left Australia for China in July 1984. From Beijing, they flew south to Tibet’s fabled capital, Lhasa. From there it was overland on some of the world’s worst roads and a crossing of the flooded Yarlong Tsangpo River in yak-hide coracles, which Howard remembers as being “like shoe boxes”.

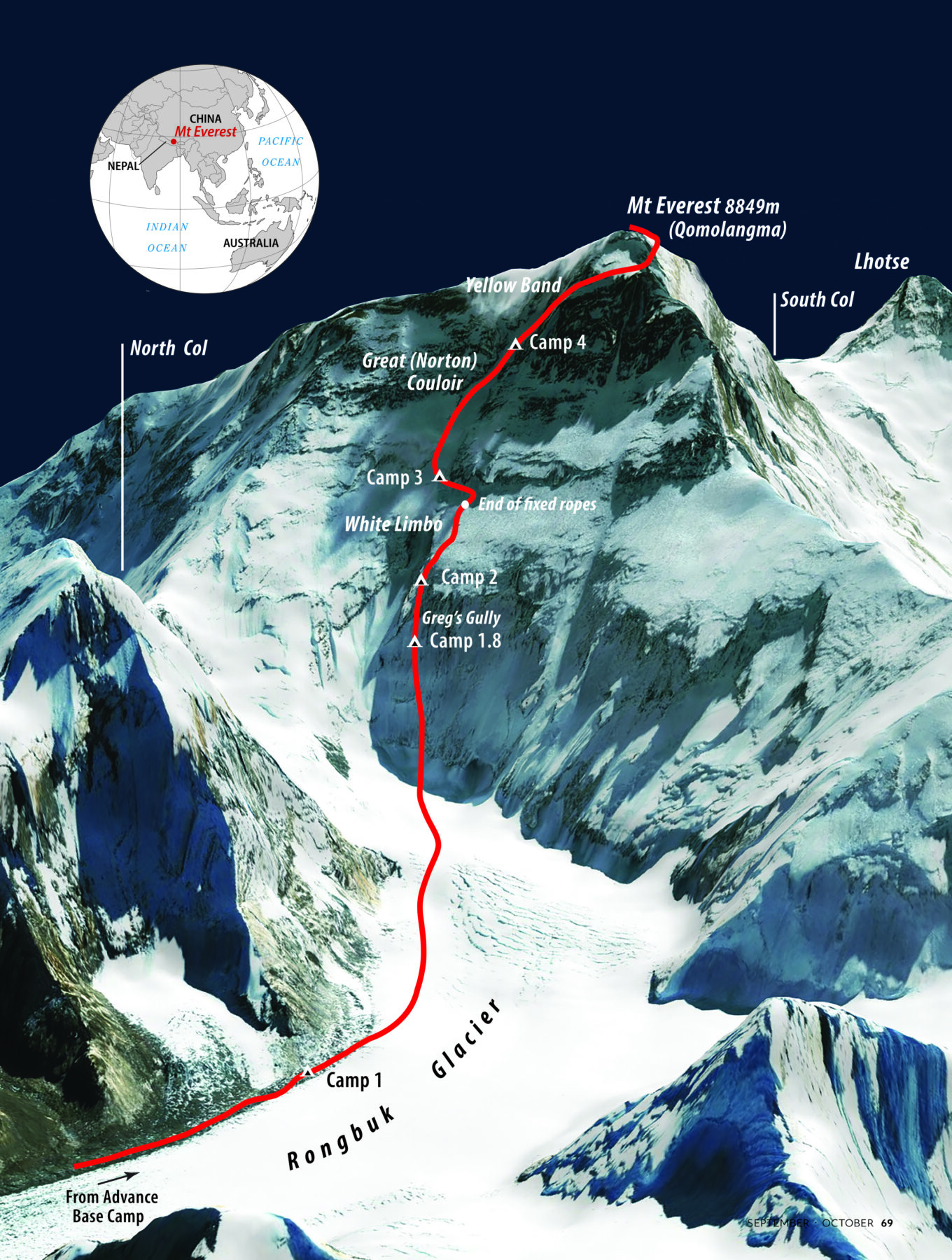

Soon after they’d entered the Rongbuk Valley, the road ended. From here they spent weeks ferrying loads 20km up the Central Rongbuk Glacier to the foot of the North Face. Advance Base Camp was established 10km up the Rongbuk. Camp 1 was established at 5750m altitude at the base of Changtse, still a couple of kilometres from the base of the North Face, because, as Steffen wrote in Himalayan Dreaming, “anywhere closer would have put the camp in the danger zone for the mammoth avalanches that periodically poured down the face”. It was the monsoon season and huge snow dumps made the face unclimbable, but the team kept busy ferrying loads for when the snow stopped and the face became safer to climb.

White Limbo

The North Face of Everest rises 3km above the ever-moving mass of ice that is the Rongbuk Glacier at 5700m. Now that they could see the face in person, the team debated their route. Eventually they settled on a new line on the left-hand side.

They would have to start up one of a series of spurs below the face’s major feature, the Great (Norton) Couloir. Above the spurs was a massive 800m-high snow slab, which Andi had dubbed “White Limbo” after a song by Australian Crawl. “Whether we would know the success of the summit or the hell of an icy death lay in part with the whims of White Limbo’s avalanche-prone slopes,” Lincoln later wrote in his book, also entitled White Limbo, about the groundbreaking ascent.

Above, the Great Couloir cut diagonally down and left from the summit, the lower section overshadowed by looming ice cliffs that made it too dangerous to climb. They hoped the higher, safer section would lead them up to the famed cliffs of the “Yellow Band” and the summit just beyond. Their plan was to fix ropes partway up the route, then, when the weather was good, punch for the top in alpine-style (fast and light, with no porters or fixed ropes).

Their first day on the mountain went well, and they fixed their ropes 300m up the face, stashing some gear. They also packed a lot of gear in the large bergschrund (crevasse) at the base of the face, a decision they would soon rue. Bad weather followed, and when it cleared, the first climbers to head back up to the face saw immediately that it had been obliterated and scattered across the glacier. Worse still, the gear left in the bergschrund had been buried. They had no choice but to try to recover it.

“We were all up there at the base of the face digging this huge hole, the world’s highest hole, to try and find

this indispensable gear,” Michael Dillon recalls. “We knew that if another avalanche came down we’d be digging our own grave.”

They couldn’t find the gear, so the climbers had to beg or borrow replacement gear from the film crew. The only thing that couldn’t be replaced were Tim’s size-12 mountain boots; instead he had to attach crampons and overboots to his cross-country ski boots.

Kitted out in borrowed gear, climbing started again. After the team had established a camp above the gear cache that they christened “Camp 1.8” (because of its poor position), the snow slopes led above to a cliff band, which turned out to be the technical crux of the route. It was dubbed “Greg’s Gully” after he climbed it. A couple of hundred metres above the intial location, they found a better place for Camp 2, at 6900m on a narrow spur that they thought would be mostly safe from avalanches.

While digging the snow cave at Camp 2, with Tim and Greg making their way up the fixed ropes below, Lincoln heard the familiar “whoompf” of an avalanche. “Sounds like a big one,” he wrote in White Limbo. Michael and Howard were filming when the avalanche cut loose from just below the summit, falling down the Great Couloir. “It fell nearly 9000 feet and it was like watching a strip mine explosion,” Howard says. The avalanche was so big the Great Couloir couldn’t contain it. Above Lincoln’s ledge, the sky filled with great billowing clouds of snow, and he had seconds to hide in his partially dug snow cave to avoid being swept away. On the fixed rope below, Greg had nowhere to go. “It was a minute or two of being bombarded with dense snow and little bits of ice…and the fixed rope just stretching and stretching as the weight of it pushed down.”

Tim was in an even worse position. He’d untethered from the fixed rope to answer the call of nature. “I was just enjoying the view, it was a glorious situation,” Tim says, “when I heard a distant rumble.” He dived for the fixed rope and hung on: “I didn’t know whether I would survive or not. It was like being in a hurricane, trying to push me off the mountain, not just the weight of snow, but the blast of air.”

It took huge amounts of patience and hard work, retreating when the weather was bad and heading up when it was good, but over a period of weeks the team eventually fixed rope to just above Camp 2. Weather permitting, they were now ready to make their push for the summit.

The final ascent

On 27 September, two months after arriving in the Rongbuk Valley, the Aussie climbers headed up the glacier for what would probably be their last chance to climb the face. Spending so much time in the low-oxygen environment had been taking a slow toll on their bodies, particularly on Lincoln who’d been having respiratory problems for weeks. Time and energy were now running low.

At Camp 2 the following day, they woke to the wind howling across the North Face, making climbing impossible. They faced a tricky decision: Wait out the weather or head back down. If they stayed and the weather didn’t improve then they would use all the supplies they’d so laboriously ferried up.

But to go down and back up again would require immense amounts of energy. They chose to stay. For three days the wind made climbing a suicide mission, while the waiting nearly drove some of them mad.

On the fourth day the wind dropped and they set off. Partway up White Limbo, Geoff’s summit bid ended. Suffering headaches and blurred vision, he diagnosed himself with cerebral oedema – where fluid collects in the brain – and he headed down. The others continued, climbing for the first time into the Great Couloir, where they conveniently found a natural snow cave in a crevasse to bivy.

The following day the weather had cleared, and they simul-soloed – climbed together unroped – up the Great Couloir. In White Limbo, Lincoln wrote: “Looking up, the snow slope seemed endless. Twenty steps then a rest, then 20 steps again.”

Camp 4 was a tent pitched on a tiny ledge carved out of the snow slope on the left-hand side of the Great Couloir. Sleep was difficult, although eventually, Lincoln wrote, “tiredness over-rode the panic of suffocating and a restless sleep followed”.

Another fine day dawned.

They traversed back into the couloir and began to climb diagonally through the cliffs above, the infamous Yellow Band, with Tim and Greg leading the way. Just below the Yellow Band, Lincoln decided to turn back because he was moving too slowly and was worried about the cold (he’d previously lost toes to frostbite on Dunagiri).

Andi was having his own problems. Partway up the Yellow Band one of his crampons broke and he had to climb the shattered yellow limestone with only one. At the top of the cliff he was able to repair the broken crampon, but in the process his hands got irretrievably cold.

Feeling the wind

Tim reached the summit at sunset and Greg joined him a short time later, the first two Australians to reach the roof of the world – in great style with no oxygen, minimal fixed ropes, a small team, a new line and – no-one mentions this – totally vegetarian.

Below, Andi had had to turn back, nine of his fingers frozen. He’d left his prescription glasses in his pack lower on the mountain. In the now defunct Mountain magazine, he later wrote, “It would be dark in a few minutes, and I would be left like an idiot, standing 50m below the peak of the highest mountain on earth, blind in prescription glacier glasses, blind without.”

There’s something otherworldly about all the climbers’ accounts of this day, a sense of their distance from safety and civilisation, of having nudged the borders of the possible. But if anyone was going to challenge the possible, it was Tim and Greg, both of whom Andi describes beautifully in Mountain: “Tim, long and gangly on first inspection, is, in fact, a nuclear-powered magician. Greg is, superficially, a much more human creature – at least he drinks – but disappointingly is a real fiend when it comes to technical climbing, and past experience showed that he had a fair working relationship with any of the local mountain gods.”

Greg would have to make the most of those working relationships that night, because he was beginning to suffer from the effects of cerebral oedema. Speaking to Howard at the Australia Museum in 2016, Greg described the descent: “I can still feel the wind from that night. It was as black as the inside of a cow at first, then the moon came up. I don’t really know where the energy came from for us. There’s gravity, you’ve got gravity on your side. But you’re cut off from reality, like you’re moonwalking, almost like floating in space.”

It was impossible to retrace their steps down the Yellow Band, so they were forced to abseil down the cliff. They had no anchors, so Tim improvised with Greg’s pack stays (two thin pieces of aluminium about 55cm long and 1.5cm wide), which he buried in the snow with the rope tied around their middle. As terrifying as that sounds, it was not as terrifying as arriving at the end of the rope in the darkness with no idea how far they were from the ground.

Sixteen hours after they left the tent at the top of the Great Couloir, they returned to an anxious Lincoln, who’d been busy melting snow and ice in preparation for their return.

Descending the following day, Howard says, Greg fell. “He nearly fell off the edge of the Great Couloir and that’s a 5000-foot drop,” Howard explains. “He self-arrested on ice, but I don’t think that was luck, that was sheer hard-man experience.”

They arrived back at the glacier in varying states. Howard says Tim seemed like he’d just been out skiing on Kosciuszko for the day. Andi’s fingers had to be kept frozen on the descent, but when Jim inspected them back at camp he had the worst frostbite he’d seen (Andi ended up having the tops of nine fingers amputated).

Greg, suffering from cerebral oedema, was mostly mute. The first time Simon remembers him speaking was when they first hit bitumen near Lhasa and there was a call to give the driver, who’d hit just about every pothole he could find, three cheers. Greg piped up from the back of the bus, “What do you mean? He was a c$#@ of a driver.”

Pushing the boundaries

Andrew Lock, the the first Australian to climb all 14 of the world’s 8000m-high peaks, said of Tim and Greg’s achievement that “it pushed the boundaries of what even veteran Himalayan ascensionists had thought reasonable. Being an oxygenless ascent of a new route on a massive, extremely threatening face on the highest peak in the world, completed in spite of the loss of key equipment, was truly extraordinary.”

Looking back now, both Tim and Greg are happy with the ascent for the same reasons that inspired them in the first place: the challenge of the unknown, and the way they were able to climb an inspiring new line in good style.

All the expedition members interviewed spoke about the combined strength of the climbers, their ability to collaborate on decision-making and deal with all the stress without confrontation. “We had a great time,” Greg says. “For whatever reason, we were happy with each other’s foibles, and that’s difficult at altitude because you can really hate someone.

“We were so totally occupied by the whole thing – in the zone is an understatement – and that’s a fascinating process on expeditions, deeper and deeper you go into the wormhole in order to stay alive.” As to the risk? “In hindsight, the risks were off the scale, they were eight to 10 on the Richter scale,” Greg admits.

What motivates someone to put themselves in so much danger? For Greg, climbing was a frame of reference that he used to interpret the world and understand himself. “I think I was using it as a measure of myself, how far I could go,” he says. “But I’m also drawn to figuring out how things work in a natural system, and what our place is in it.”

When I ask if he now understands our place in the world, Greg says, “I do. How puny it is.”