‘The bush calls us’: the defiant women who demanded a place on the walking track

Many Australians feel drawn to explore the bush on foot. Bushwalking offers a chance to escape the city, forge friendships, explore beautiful scenery and keep our bodies and minds healthy.

But the bushwalking track wasn’t always a place where women felt welcome.

In the 1920s and ’30s, some people scoffed at the idea women could handle rugged encounters with nature. The bush was considered a place for men.

Besides, how could women walk rocky paths and steep hills in their long skirts and dainty shoes?

But some courageous women walked anyway. The Melbourne Women’s Walking Club formed in 1922, and was the first of its kind in Australia.

The women were criticised and sometimes harassed, especially when they experimented with wearing pants – or even shorts.

But the women found solace in friendship and a shared love of nature. New research sheds light on the stories of these remarkable women.

The birth of a movement

First Nations people have walked the Australian landscape for many thousands of years. European walking for leisure dates back to the early settlers, though the word “bushwalk” was coined much later.

As Australian scholar Melissa Harper has shown, walking became more popular as a pastime in the early 1900s. A number of male-only clubs spawned, but women were excluded – only on the occasional Ladies’ Day were they permitted to walk with the men.

In 1922, a group of women decided they wanted their own bushwalking club – and the Melbourne Women’s Walking Club was born. The women defied societal expectations by walking in bushland across Victoria and beyond – sometimes for weeks at a time.

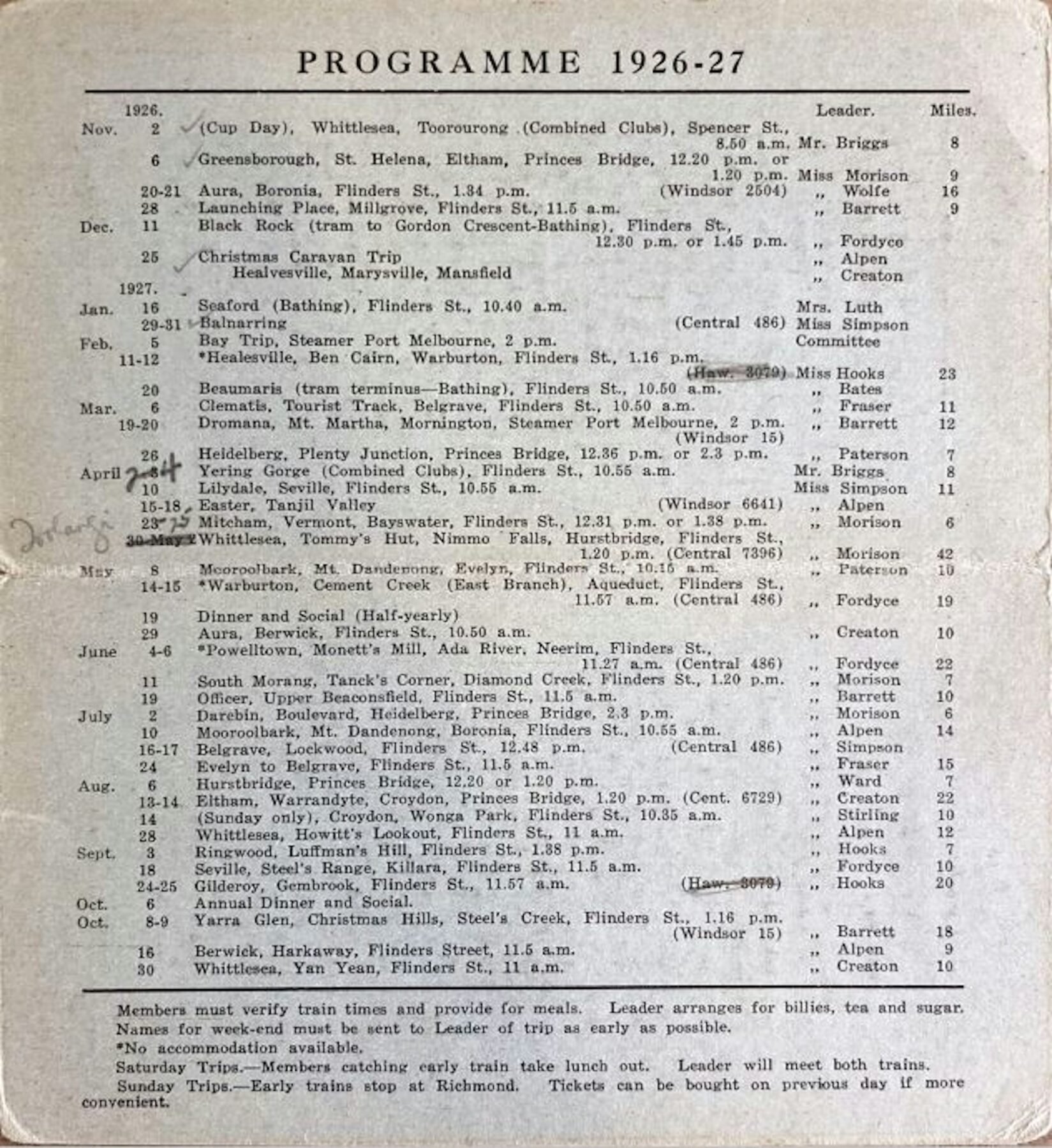

The annual program offered between 30 and 40 walks catering to a range of abilities, as well as a busy calendar of other social events.

Taking a hike with the Melbourne Women’s Walking Club

In a time before most women had access to cars, club members typically met at Flinders Street Station then took a train to the start of their hike. Walking destinations included Wilson’s Promontory, the You Yangs, Phillip Island, the Grampians, Anglesea and Mount Buller.

In the club’s early years, the women waited until they were in the bush, hidden from public view, before stripping off their bulky skirts and donning jodhpurs instead. By the 1930s, some women even wore shorts.

The women carried a communal billy and took mealtimes seriously. For a weekend walking trip, the recommended packing list for each woman included:

- creamed rice

- pre-cooked stew and vegetables

- tinned pineapple and cream

- grapefruit

- eggs and bacon

- steak for grilling over the campfire

- six teaspoons of tea

- four teaspoons of coffee

- two crumpets (for tea on Sunday)

The women carried homemade sleeping bags for overnight and multi-day walks. Sometimes, pack-horses joined the journey.

On caravan trips, such as the one depicted in the image above, the women were driven into the bush in a specially converted open-side furniture van.

Challenging journeys

Not every trip by the Melbourne Women’s Walking Club went exactly to plan.

One club member, Margery Luth, recounted in the club’s journal a particularly challenging walk to Mount Buller in 1938. As they hiked, a hailstorm hit. They stopped overnight to sleep in a shed, but the roof leaked, and it flooded. On the way home, the bus broke down and was involved in an accident. Luth, however, found the trip “thoroughly enjoyable” and wrote lyrically of observing the bush after dark:

It was a heavenly night […] all the beauty of the bush was visible, the feathery foliage of the wattles, the sparkle of the gum leaves, the tracery of tree ferns and the tangle of undergrowth.

On another walk in December 1928, a group became lost for two days in the Bogong High Plains in punishing December heat. Their food supplies diminished and they ran out of water. The women eventually found shelter for the night in a walkers’ hut, where one woman photographed the group grinning wildly.

And tragically, on a bushwalk in 1937, one club member died after an accident. Olive Sandell, a young clerk at the Melbourne Children’s Hospital, fell and hit her head while hiking the Cathedral Ranges. She died surrounded by her fellow walkers.

For some women, even getting to the track was a challenge. For example, a new mother, writing in the club’s journal, expressed how she missed her bushwalking friends and joked about starting a “rival walking club” consisting of herself, her toddler and her dog.

Marriage and domestic responsibilities could also prevent women from walking. In 1936, the journal’s editor wrote of a club member’s impending marriage, and expressed her hope that the soon-to-be husband would not force his wife to “forgo tripping with the troops to keep him in holeless socks and juicy steaks!”

A controversial pastime

Members of the Melbourne Women’s Walking Club cherished their time in the bush. They formed firm friendships and laughed and sang together. They rejoiced in escaping their domestic responsibilities and the busyness and pollution of city life.

On the sweltering Bogong High Plains trip in 1928, a friendly farmer offered the walkers a swim in his dam. The women only had one pair of bathers between them, but landed on a solution: one walker would wear the bathers and jump in the dam, and when she was immersed in water, would wriggle out of the bathers and throw them to the next would-be swimmer, and so on. The women’s written accounts express their enjoyment of this small, shared scandal.

While some observers welcomed the women’s disregard for convention, others were highly critical.

In a newspaper article in 1932, the Archbishop of Brisbane, James Duhig, described women bushwalkers in male clothes as “absolutely nauseating”. He warned wearing pants might encourage risk-taking, saying:

I know that young girls dressed in men’s garments would go to places where they would never venture in their proper attire.

Other critics accused the women of attention-seeking or simply following a fad.

The women often attracted unwelcome attention and lewd comments, especially when taking public transport to the beginning of each walk. They felt relief at beginning the bushwalk, safe with friends and far from judgement.

True trailblazers

The Melbourne Women’s Walking Club was the first of its kind in Australia. But other women of the era also took their place on the walking track. They include Jessie Luckman of Tasmania, Marie Byles and Dot Butler of New South Wales, and Alice Manfield, who led guided walks on Victoria’s Mount Buffalo.

Thanks in part to the audacity of early female bushwalkers, it is no longer controversial for women to walk unchaperoned or wear shorts.

But that doesn’t mean women don’t still face discrimination and safety threats in outdoor spaces. There is a way to go before everyone feels welcome and safe in Australia’s great outdoors.

Many members of the Melbourne Women’s Walking Club went on to become committed conservationists. Several played vital roles in advocating for the protection of the natural spaces we enjoy today.

For example Jean Blackburn, an enthusiastic club member from 1934 until her death in 1983, played a leading role in the creation of national parks in Victoria.

The club survived the stresses of the Second World War and a slump in membership in the 1950s. Today, more than 100 years after its inception, the Melbourne Women’s Walking Club is still going strong. In fact, today, it boasts its largest-ever membership.

So, next time you set out for a hike, spare a thought for the extraordinary Australian women who fought for their place on the bushwalking track – and paved the way for generations to follow.

Ruby Ekkel is a PhD candidate at the Australian National University.

Special thanks to Sheila Hirst from the Melbourne Women’s Walking Club for providing archival images. Images adapted from the Melbourne Women’s Walking Club archive at the State Library of Victoria, the MWWC book Still on Track: 100 years of Melbourne Women’s Walking Club 2021, Uphill After Lunch: the Melbourne Women’s Walking Club 1922–1985 and the National Library of Australia.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.