On Christmas Eve 1974, nine-year-old Rodney Gregg and his identical twin brother were spending a lazy afternoon riding around Nakara, one of Darwin’s northern suburbs, on bicycles they’d received from Santa Claus the previous year. With the only proviso being to return home before dark, the boys were making the most of the freedom their treadlies gave them, and they happily anticipated what the jolly man might bring them overnight this time. The afternoon was overcast and the dense monsoonal clouds that hung low over the Top End’s capital were dumping their contents, on and off. But the intermittent soakings brought little respite from the heat and the wet season’s searing humidity left the boys feeling like they were pedalling through thick, warm soup.

Earlier that day, at 12.30pm, the Bureau of Meteorology issued a first warning that the city of Darwin was threatened by a cyclone, expected to make landfall early on Christmas morning. This was 12 hours before the onset of destructive winds and 12 hours before Rodney’s father would be nervously waking him and his siblings, urging them to leave their bedrooms in search of a safer place to shelter.

Rodney becomes emotional as he thinks back to that night, 50 years ago. “Before we left our room, the last thing I remember seeing was the corner of the roof and ceiling starting to lift,” he says. “The lightning was so bright, it lit everything up like daytime and we fled down the back steps of the house.”

Sensing the building was no longer safe, Rodney’s father ushered the family of seven into an old station wagon under their house. About 15 minutes later, the whole upstairs of their family home caved in.

“I can still remember the sound of hundreds of pieces of roof sheeting scraping across the roads,” Rodney says. “My brothers, sister, cousin and I spent the rest of that night crouched down the bottom of the station wagon, with mum and dad in the front. All night, we were being buffeted around by howling winds, driving rain and the worst screeching sounds you can imagine. As the eye passed straight over us, everything suddenly fell silent. But then we got the opposite side of the cyclone, and it was even more intense.”

When Rodney and his family finally ventured out of the car at dawn on that grey, sodden Christmas morning, all they could see was destruction in every direction. And all they had left were the clothes they were wearing.

Four days earlier, on 21 December 1974, the BoM had issued an alert of the possible development of a tropical cyclone in the region and it was given the name Tracy. But most Darwinians paid little heed. Earlier that same month, Cyclone Selma had been predicted to be a potentially devastating weather event for Darwin, but she changed direction at the last minute and left little more than heavy rain in her wake. And so it was that on Christmas Eve, a perfect storm of complacency borne out of near misses, and the distraction of Christmas festivities, meant precious few were prepared for the thrashing that was to come.

In the suburb of Ludmilla, 11-year-old Christine Ross was sheltering with 12 other family members who’d gathered to celebrate Christmas in their small fibro-clad home. “We moved to Larrakia Country [Darwin] when I was four and I think for a lot of my mob, we pick up on things that maybe non-Aboriginal people don’t,” says Christine, an Arrernte/Eastern Arrernte/Kaytetye woman. “We look for things happening with the animals, when birds start to go crazy and when weather starts to change. But despite that, and even though we lived in a cyclone town whose residents were forever being given warnings, I don’t think any one of us was prepared for what happened that night.”

While the children went to bed, dreaming of feasts and festivities, Christine’s father sat up listening to a transistor radio for updates. As the storm began surging, he woke the family and first moved them to the bathroom, before guiding them to the neighbour’s home, which was made of brick and deemed safer.

“In the end, I reckon there was 25 of us taking shelter in the neighbour’s house underneath a pool table,” Christine says, her voice cracking. “The men had to hold the doors shut, otherwise they would’ve blown in and debris would have come flying in everywhere. My dad and the other men did a lot of heroic things that night for our family.”

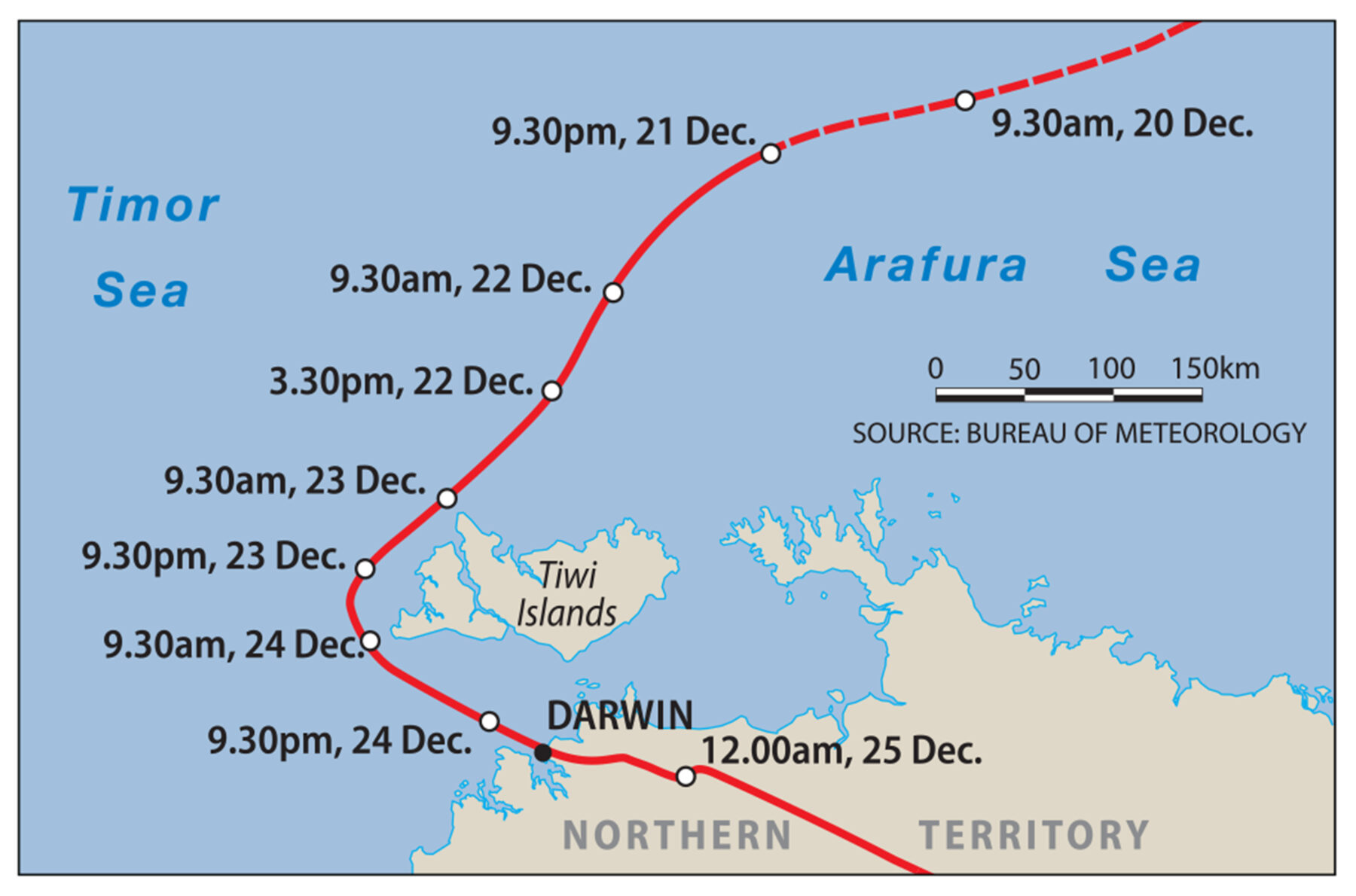

Making landfall

Tracy first made landfall most likely at East Point, on the north-east tip of Darwin Harbour, sometime after midnight and then wildly ploughed her way through the tropical city (see map below). The peak wind gust recorded was 217km/h at about 3.05am at Darwin Airport, before the anemometer (wind gauge) was destroyed. The torrential rain measured 195mm in 8.5 hours, but at 3.30am the pluviometer (rain gauge) was damaged and so the total rainfall is unknown. Regardless of exact measurements, the wind and rain combined were enough to render about 80 per cent of the city’s buildings destroyed or uninhabitable, their hapless occupants left cold, soaked and frightened.

A couple of hours earlier, Dr Stephen Baddeley had clocked on for duty at the casualty department of the Darwin Base Hospital with two bottles of champagne tucked under his arm, ready to toast Christmas Day with the other medical staff rostered on to work the holiday night shift.

“I can remember walking towards the casualty department at around 11pm and it was blowing wildly,” Stephen recalls today. “I was jumping in the air and getting blown along and thinking it was great fun. I was the only doctor on duty that night in casualty and, when I got there, we had no patients.”

That, of course, was about to change. As the cyclone unleashed her full power, Stephen remembers the roar being so loud he couldn’t hear himself talking to the person beside him. At last, the eye of the storm arrived, and with it, a deluge of patients that were to test the mettle of the first-year doctor.

“The first patient was a sailor who had lacerated his hands climbing the poles covered in oysters after his patrol boat was driven into the wharf by the huge winds. And so, I had to sew this fellow up,” Stephen says. “The next thing that happened was the back door of casualty burst open and in rushed the senior surgeon Alan Bromwich, an old English war surgeon. He was the first doctor to arrive, even though the winds were still very high.”

About 20 minutes later, the wounded began to arrive. So too did the bodies of some who’d been tragically killed, carried in on doors blown off their frames that had been turned into makeshift stretchers. For these lost souls there was little medical staff could do other than stack their bodies against a wall while continuing to treat the injured.

“I remember the enormity of it came to me at one stage when there was a panicking crowd with their injured relatives and friends trying to get into the casualty department,” Stephen says. “Among those panicking were policemen. They were human beings too and were reacting just like everyone else.”

Stephen pauses as he swallows his emotions so he can speak again. “One of the horrors that is an enduring memory for me was seeing a dead baby being brought in. And every time another dead body had to be put on the pile, the deceased baby was lifted and put on top, out of respect.”

It was at this point that Alan, the veteran war surgeon, looked over at Stephen and said: “The only thing missing right now is the sound of guns.”

Stephen describes Alan as a hero, explaining that he set up three operating theatres to be manned by two assistant surgeons and a registrar-in-training while he triaged the wounded according to urgency, not a common practice back in the 1970s.

“There was no sitting down for a day; we worked our guts out for at least 24 hours,” Stephen says. “Alan saved dozens of lives that day without doing any surgery. And I never saw him fazed until he was told that the senior anaesthetist was dead. The anaesthetist only lived down the street, and he tried to come into the hospital early on in the cyclone but was struck by a piece of corrugated iron and was almost decapitated. That was the first time Alan looked really taken aback.”

Stephen estimates as many as 90 per cent of the injuries they were treating were caused by lacerations from flying debris, notably corrugated iron roof sheets, as well as “glass missiles”.

While the medical team worked tirelessly throughout Christmas Day, Tracy moved on, slackening into a rain depression, crossing the Adelaide River about midday, and then moving slowly south-east across southern Arnhem Land. Bewildered residents, who should have been unwrapping presents and preparing prawns and salads, were instead slowly extricating themselves from the rubble and surveying the extraordinary damage.

An entire capital city of Australia had been decimated. Dozens were dead. No foliage was left on the battered trees; no birds heralded the start of the new day and no insects buzzed their usual summer soundtrack. The city was left with no power, no water, no sanitation and no communications. Both local radio stations had failed. After all the ferocious noise of Tracy, an eerie hush and hazy pallor descended over the formerly bright and vibrant city.

Back in the hardest hit northern suburbs, Rodney Gregg and his family picked around the ruins of their home, looking for anything they could salvage. “I had no shoes and I stood on a piece of corrugated iron and then later, I had to have a tetanus shot,” Rodney says. “We looked for our things but there was almost nothing left – it was total annihilation. Mum grabbed our passports and some photos of her wedding to dad. But we pretty much lost all our family photos.”

Christine Ross and her mob emerged on Christmas Day to find their roof had blown off and the resulting water damage had left their home uninhabitable. They took refuge at St John’s Catholic College, staying in the classrooms. Likewise, Rodney and his family retreated to their local-school-cum-evacuation centre.

Chaos reigns

While chaos and confusion reigned in Australia’s Top End, the rest of the country awoke to a cheery Christmas Day, blissfully unaware of the struggles of their fellow Australians in the north. Remarkably, Acting Prime Minister Dr Jim Cairns was not informed of the devastation of the northernmost capital city until nine hours after the cyclone had struck. Prime Minister Gough Whitlam, on leave in Europe, was also ignorant of the news.

In Canberra, Major General Alan Stretton, the Director-General of the newly formed Natural Disasters Organisation, awoke to an early morning Christmas Day phone call at his home, reporting that Darwin had been hit by a cyclone, according to a report from the Cyclone Tropical Warning Centre in Perth.

Stretton was then fortunate enough to make a brief phone call to a police sergeant in Darwin to confirm the news. It was the last communication he could make to local authorities before the lines went dead and on the strength of the rather flimsy reports he’d managed to hear, Stretton began to orchestrate the biggest relief operation in Australia’s history. He called on the Army to mobilise 200,000 rations for immediate dispatch, the largest order placed since World War II, and enough to feed the population of Darwin (roughly 45,000 people at the time) for four to five days.

By late that evening, Stretton was landing in Darwin on a RAAF plane with one assistant staffer and a medical team at the ready. The runway had been cleared of debris in anticipation of their arrival and was lit with car headlights and two kerosene flares. “The reason for my journey was to make an assessment of the local situation and damage and then to return as quickly as possible to coordinate the national effort to support the local authorities,” he later explained in his memoir, The Furious Days: The Relief of Darwin. After arriving and gathering information, his assessment of the local preparedness for such an event was scathing. “Although it was obvious from 9am on 24 December that Tracy was on a direct course for Darwin … there is little evidence that anyone in authority in Darwin heeded this warning,” he wrote. “Who is to say how many lives would have been saved if the authorities in Darwin had taken energetic steps to prepare the city to meet the oncoming disaster?”

Jim Cairns had, earlier that day, verbally granted Stretton supreme authority for his time in Darwin, but instructed the military man and former barrister to act in a civil capacity, and not enact martial law. “At that stage, I had no idea how I would go about taking charge of a capital city and exercising the authority of the Australian Government,” Stretton recounted in his memoir. He added that “to place one individual in charge of the whole operation, including complete control of Darwin” was unprecedented in Australian history: “There was no legal basis for such an appointment and there were no legal powers that could be exercised. The irregular and informal way in which it was done was extraordinary.”

Stretton did find a way and it earnt him the title of Australian of the Year just 12 months later. But, as he stood knee-deep in devastated Darwin, the first step he took was to restore communications between the police, Army, RAAF and the MV Nyanda, which had entered Darwin Harbour just after Tracy hit. “It is indicative of the state of shock of all those who endured Cyclone Tracy that some 18 hours after the cyclone had passed, there had been no effort to establish these vital communications,” he wrote. “After a disaster, the first priority will aways be the re-establishment of communications.”

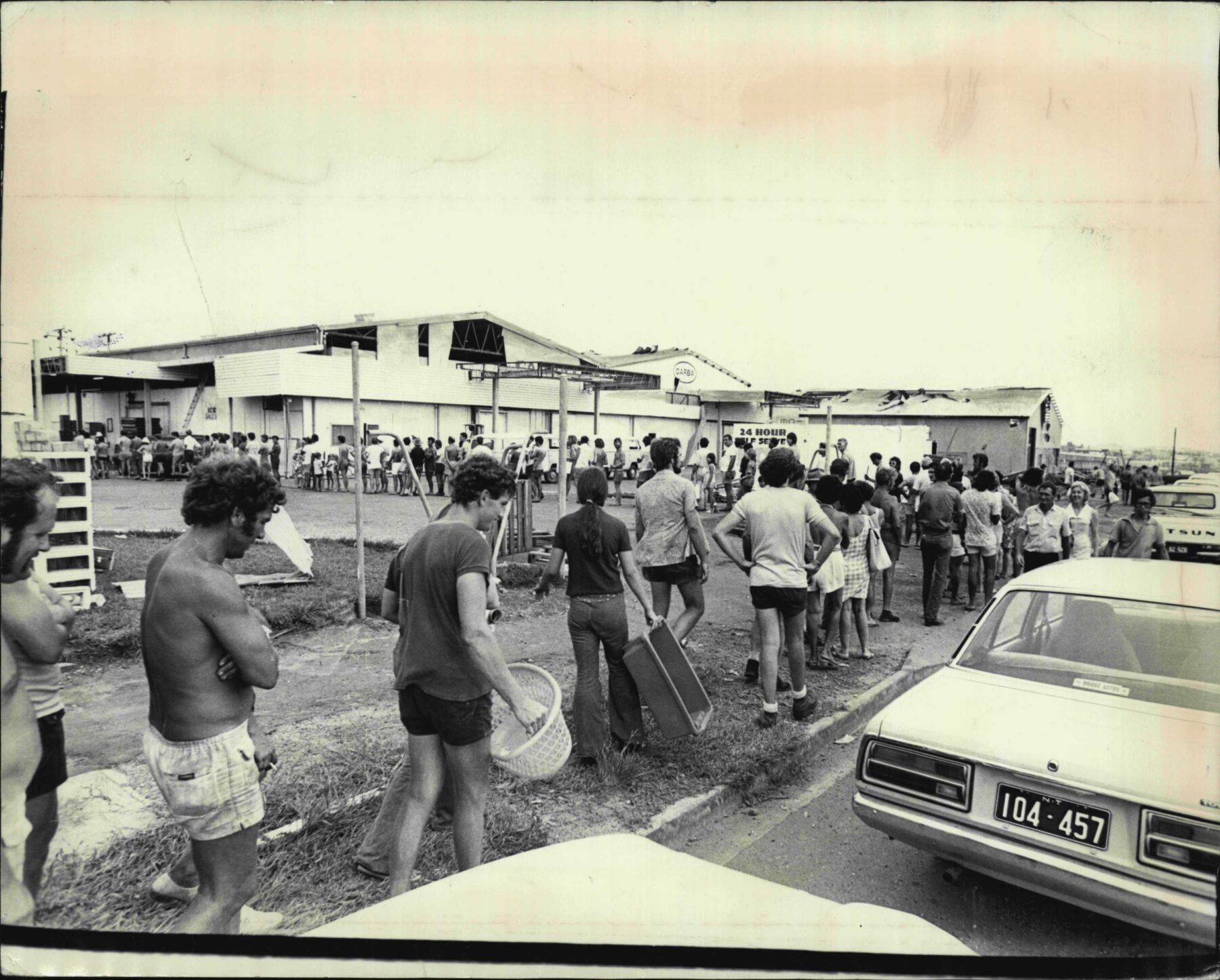

Interestingly, Stretton decided that the armed forces would be confined to a supporting role by helping with the supply and provision of essential goods, but that the handling of local problems would rest on the people of Darwin themselves, albeit under Stretton’s leadership. “I decided that if the 45,000 people of Darwin were to be saved, they would do it themselves. This would give them a challenge worth fighting for,” he wrote. “In the event, the people of Darwin responded magnificently to the challenge they were given. They came out of the ruins and worked day and night to restore what was left of their city. It was the citizens themselves who ran the 24 executive committees that put the city back on its feet in under a week, and which organised the Darwin end of the most massive airlift Australia has ever undertaken. This was achieved in the unbelievable time of five-and-a-half days.”

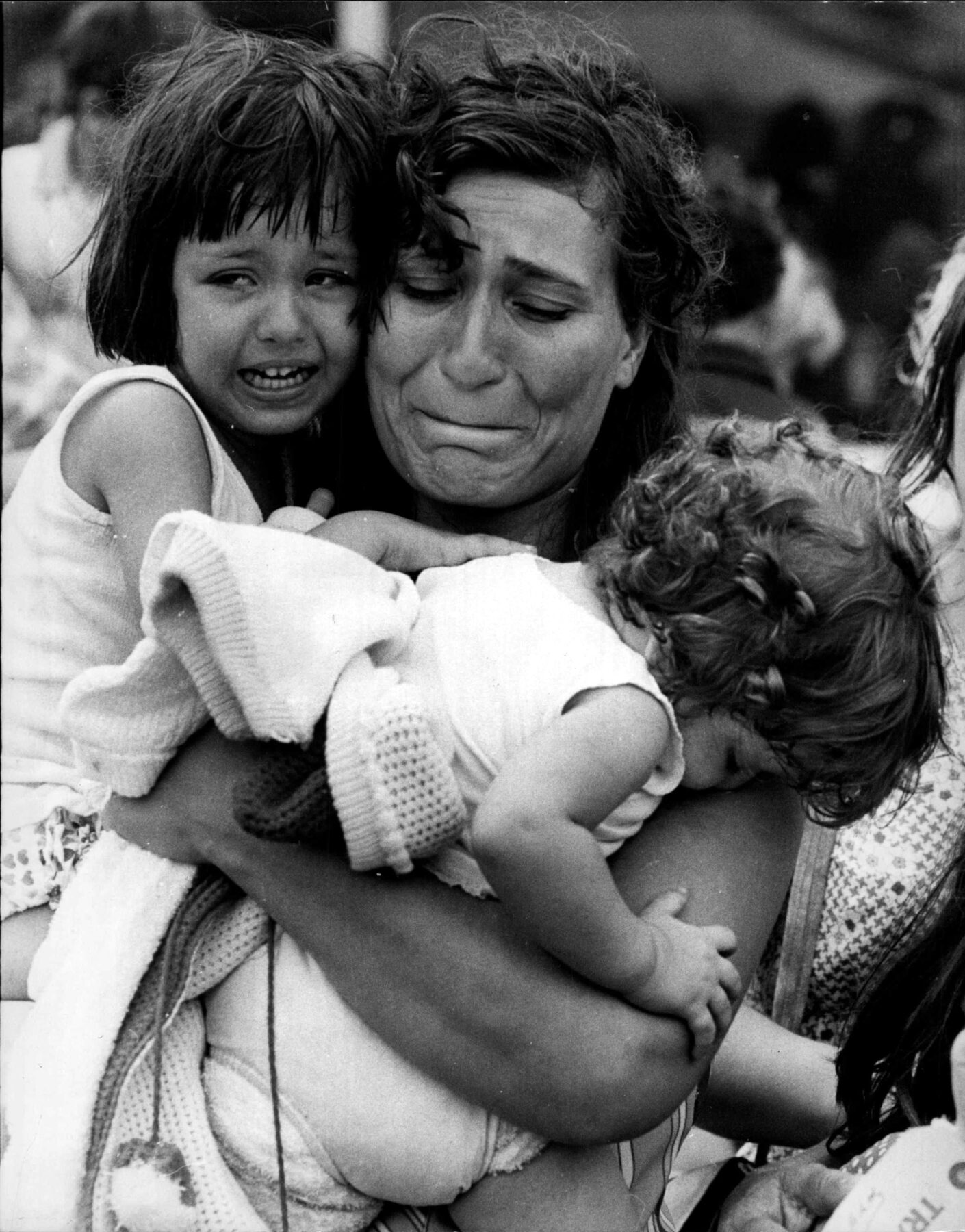

Stretton deemed the mass evacuation of residents necessary to prevent the spread of disease, and to solve the problem of housing and feeding the population while essential services were being restored. The Red Cross, whose staff had worked tirelessly since the disaster struck, scrambled to try and keep track of the refugees’ movements, and provide answers to distressed friends and relatives seeking information about the welfare of loved ones.

Mass evacuation

Rodney and his brother were among the 35,000 or so who were evacuated from Darwin, either by plane or car. “Mum and dad stayed behind to help but my brother and I were put on a huge jumbo [jet], to stay with my dad’s friend in Brisbane. The plane was absolutely chock-a-block full of people and yet nobody said a word,” Rodney recalls. “We landed in the dark and we went through a hangar where there were tables and tables of books, toys, clothes – whatever we wanted. But my brother and I felt we couldn’t take anything because we thought it wouldn’t be polite.”

One Boeing 747, which would normally seat 365 passengers, was crammed with 674 evacuees in one flight – a total of 697 people once crew were added, setting a new world record. The extra passenger weight was made possible by the plane being unable to refuel in Darwin and the lack of luggage.

Christine also remembers being evacuated by air, with her mother and seven siblings, while her father stayed behind to help with the rebuilding. “It was emotional saying goodbye to dad, not knowing when we were going to see him again,” she says. “We were evacuated to Brisbane and stayed in the Wacol Barracks. One thing that always stuck out was how incredible the rest of Australia was at stepping up. We were looked after so well and treated like rock stars; they wrapped their arms around us the whole time we were away.”

As news began filtering out to the rest of the country, Australians responded in a force of collective compassion and generosity. There were telethons, charity concerts; even a dedicated song, Santa Never Made it into Darwin, was released, recorded by Bill and Boyd, with all proceeds donated to the relief effort.

On Boxing Day, Salvation Army officers from Queensland and Perth arrived in Darwin, with more flying into the city during the following week. Altogether, the Salvos served more than 25,000 meals over four days at Darwin Airport, and worked indefatigably to distribute essentials such as clothing, beds, hurricane lamps, candles, kerosene, soap, and razor blades.

They also helped support the evacuees who landed in various locations around the country. James Condon, former commissioner of the Salvation Army, headed up the Mount Isa response, in outback Queensland, providing crisis accommodation, as well as sorting through the community’s donations and allocating them to the evacuees who found themselves unexpectedly in the small mining town.

“It was an amazing response from the whole Mount Isa community,” James recalls. “I can remember having many sleepless nights helping people and I can remember putting my arm around people who were crying and distressed and, if it was appropriate, offering to pray for them.” James says the Salvos’ attempts to encourage and empathise with Darwin residents in their despair, by talking and listening to them, was just as vital as fulfilling their physical needs. “The psychological impact of these disasters on people can be lifelong,” he observes. “Some people never recover. It leaves a real scar on them.”

That has been the difficult experience of Robyn Cooper-Radke, who was eventually diagnosed with complex PTSD (post-traumatic stress disorder) after going through the harrowing experience of Cyclone Tracy at age 12. “Many a time that night, I thought we were going to die,” Robyn says. “That was my biggest fear. And it was so cold and wet. The next day, when the cyclone had passed over, we thought we were the only people left on Earth.”

Throughout her life post-Tracy, Robyn says, she’s experienced mental health challenges, including depression and suicidal ideation. “Tracy’s always affected me,” she says. “When my two sons were kids, I would struggle at Christmas time. All those intrusive thoughts would come back. I was hypervigilant, and always watching and waiting for a cyclone. In windy weather, my anxiety would go sky-high. I became addicted to prescription medication … I had to learn to live my life again through a wonderful psychologist.”

Robyn eventually found comfort in moving back to her homeland of New Zealand. She is now retired but plans to journey to the Top End for the anniversary. Like many survivors, she dates her life in two time periods – pre- and post-Cyclone Tracy. It’s become a mark in time for the city too, with only a few key buildings left intact to pay homage to the pre-Tracy days.

Heartbreaking death toll

With so few dwellings still standing after the onslaught, the death toll seems disproportionately low to many people. It is widely reported as 71 deaths. However, Jared Archibald, curator of the Museum and Art Gallery of the Northern Territory (MAGNT), says the correct number is 66. Both Jared and the City of Darwin Council have independently conducted research, scouring the records and available evidence, and both arrived at the same number. Jared explains the discrepancy came about due to a double count of five people who were missing at sea.

Certainly, the commemorative plaque outside the Darwin Civic Centre only lists 66 names, albeit with a few incorrect spellings and with some people placed in the wrong category. According to Jared’s research, it should read that 21 people died at sea, and 45 on land, whereas the plaque erroneously lists only 13 as lost at sea.

But the rumours that many more than 66 died on that fateful night – possibly in traditional Aboriginal communities or alternative communes – continue to persist, 50 years later. Jared explains why this is unlikely to be true. “It’s not like a bomb went off,” he says. “This was a gradual storm that started small, grew to become a shockingly bad cyclone, then came from the other direction, and then calmed down and went away. And so, people had time to find ways to survive.”

He does acknowledge, however, that the death toll only includes those who were killed during the cyclone. Others that died from their injuries later are not included in the official count. “When you think it through, it becomes more and more difficult to define what a death from Cyclone Tracy is, the longer time passes from when the cyclone passed through,” Jared says. “For example, you cut your foot on broken glass or nails on Christmas Day 1974, you contract melioidosis or tetanus or gangrene, and you end up dying two months later. Are you a victim of the cyclone, or are you a victim of one of the dangers of just living life in Darwin, as this could have happened at any time in your life here?”

Revisiting the tragedy

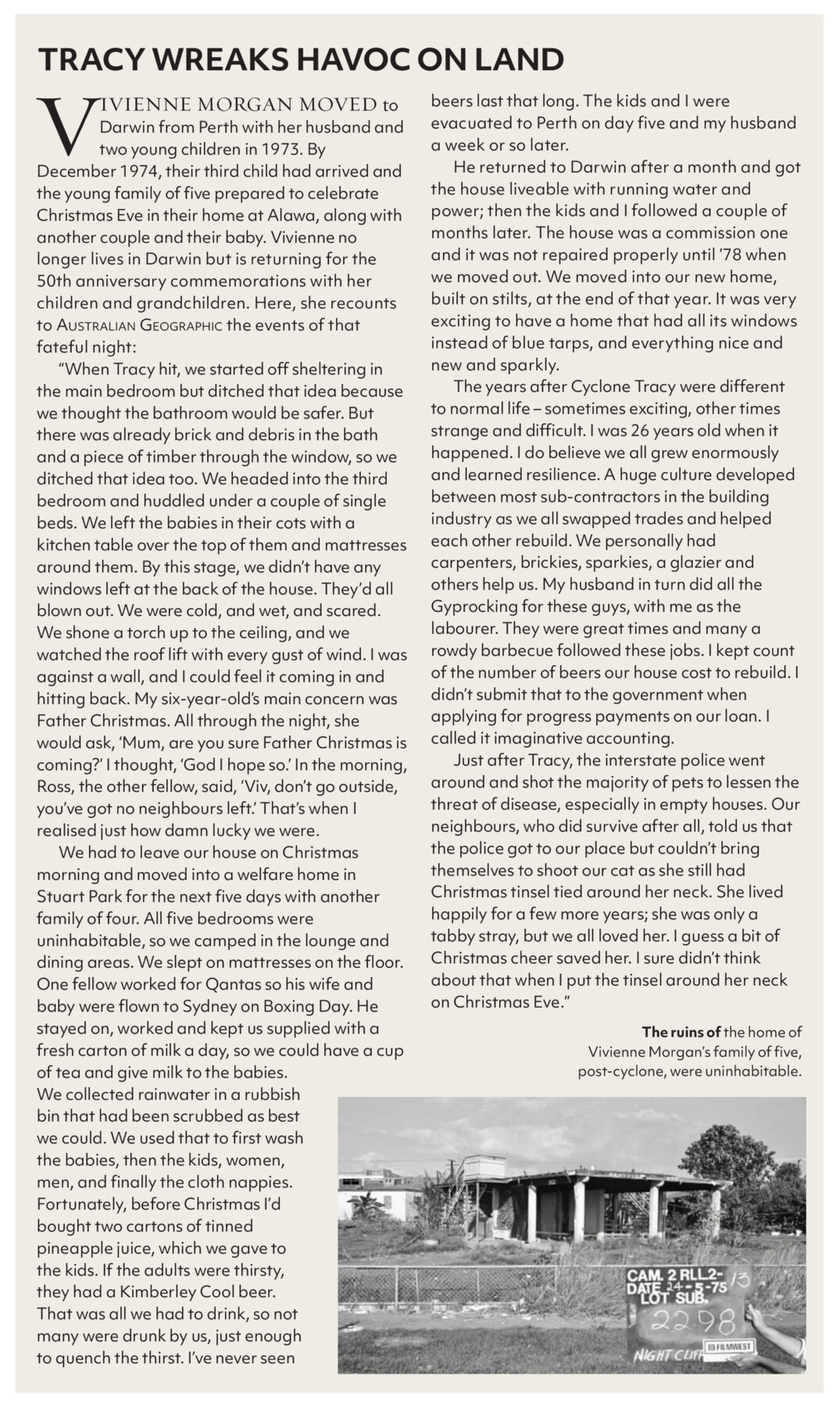

One of the best places to learn about the disaster and its ongoing impact is at MAGNT, where there is a permanent Cyclone Tracy exhibition. It’s also a meeting ground of sorts for pilgrims who return to remember. One of the most talked about activations in the museum is a lightless sound booth, which plays an original recording of Tracy’s Category 4 cyclonic winds. It’s an eerie experience for anyone, and potentially triggering for survivors. Also included in the comprehensive exhibition is a replica of a typical pre-Tracy, Darwin home. These standard designed houses were often erected on stilts, sheeted with fibro, topped with a corrugated iron roof and featured walls of louvres to catch the Timor Sea breezes.

Stretton’s assessment of Darwin’s building standards prior to Tracy was unsparingly critical. “In the wake of Tracy, Darwin, capital city of the north, was left in ruins,” he recalled. “The irresponsible administration of a succession of governments that allowed people to build houses with little regard to the threat from cyclones, produced the inevitable result.”

A significant percentage of the city’s homes were government built and owned, and uninsured, as Darwin was still under the governance of the Commonwealth until 1978. Overseeing Darwin’s construction and maintenance activities at the time was the Commonwealth Department of Housing and Construction (DHC). Its structural engineers were responsible for the design of the government-issued homes and flats and believed them to be cyclone resistant. Given the level of damage, there was no question building regulations needed to change. “It was the worst disaster due to building failure in Australian history, and it was an engineering failure,” George R Walker, a structural engineer and academic, wrote in 2010 in the Australian Meteorological and Oceanographic Journal.

An investigation was inevitably conducted, and the report’s recommendations were implemented. After a slow start, the rebuilding of Darwin was largely completed in three years under the guidance of the Darwin Reconstruction Commission, ultimately headed up by former Brisbane Lord Mayor Clem Jones.

“Just under a year after Cyclone Tracy, the first reconstructed house was handed over, to be followed by hundreds, which became thousands, over the ensuing two or three years,” Walker wrote. “As a consequence, Darwin can probably claim to be the strongest city in the world in respect of wind resistance.”

The knock-on effects of these building code and regulatory changes were felt all over Australia, as the new standards were adopted nationally. “The zoning of cyclone regions and recognition of the importance of fatigue failure of cladding fastening systems and internal pressures in the wind code, is a direct impact of Cyclone Tracy, as is the nationwide requirement for housing to be structurally engineered to resist wind loads, which in many ways was probably the most radical impact,” Walker wrote.

The rebuild

It’s estimated that only 50 per cent of residents ever returned to Darwin, and yet the population continued to steadily grow, reaching about 140,000 in 2021, according to the Australian Bureau of Statistics. Rodney and his family were among those who chose to pick up the pieces. They returned home six months after Tracy.

“Lots of our neighbours never returned,” Rodney says. “Friendships were forged among those who came back. But I think Darwin sort of lost its innocence in ’74.”

By the time Rodney and his brother returned to the Top End, their father had converted their former two-storey home into a single-storey house, with a caravan for bedrooms. He converted the laundry into a shower room, and the carport into a living room. Rodney and his family continued to live in this unconventional configuration until the new building regulations were announced, but his father soon realised it was too expensive to rebuild in accordance with the new cyclone code.

Pre-Tracy, their home had been grossly underinsured. And so, they became yet another family who left Darwin for good. Rodney later returned to the Northern Territory to work as a schoolteacher in Katherine and lives there to this day.

Christine’s family eventually returned to Darwin too and the family of 10 lived for some time in two caravans while they rebuilt their home. “I think people back then were incredibly resilient,” she says.

“We had to think on our feet and adapt. It made us stronger. It brought us together. But thank the Lord we’ve never had another cyclone on the same level as Tracy, although many have come and gone.”

Christine now lives in Perth, where she runs a consultancy business specialising in Indigenous employment programs. But she insists that Darwin will always be home and, like Rodney, plans to return for the 50th commemoration.

“For those of us old enough to remember, it’s one of those things that stays with you forever,” she says.

“We had to rebuild our city, but we came back bigger and better. The Territory spirit is still there, the pride we have in our hometown, and the love and support we gave to each other before, during and after Tracy.”