It’s December 2023 and Dan Prochazka and his partner, Nicola Beatrix, are awake early. They emerge from their tiny house near Castlemaine in west central Victoria into a frosty summer morning. Toddler daughter in tow, they walk 20 steps to a hangar-like open garage with tractors and building supplies at one end and a camp kitchen at the other. A kangaroo skin is slung over the back of a chair as a warmer. “Roadkill … found about 300m from here yesterday morning,” Dan says, nodding to a pot of dark kangaroo stew bubbling away on the gas stove. Dan and Nicola are on a pathway to sustainable living. But turning the dream into reality takes lateral thinking and a lot of hard work.

Looking west from the temporary kitchen, past a pegged-out barren plot destined to be a veggie garden the size of a footy field, is the heart of Dan and Nicola’s social experiment – an “intentional community” known as Open Field Co-Living Homestead. For 170 years, so-called intentional communities have created a parallel social and cultural landscape in Australia. They attract people who believe the world would be a better place, both socially and environmentally, if we humans lived in closer communities. Yet, despite the purity of the ideal, communal living is generally perceived as an anomaly; a weird social experiment that’s the domain of hippies or religious radicals. It can be all of that, but it can also be an expression of our higher ideals – utopia.

The first known intentional community in Australia was Herrnhut commune in western Victoria, founded in 1852 by a quasi-religious group of German Protestant immigrants led by Johann Friedrich Krummnow. The Germans established a school, businesses and a village, but with heightened visibility came derision and fear. Angry at the influx of migrants and indigenous groups who were drawn to Herrnhut, the locals undertook a relentless policy of harassment and legal warfare until, in 1889, they succeeded in shutting down the utopian commune. We naturally fear what we don’t understand, yet the pull to live communally can be as straightforward as being happier living with other people. Like many young people, Nicola moved through a series of share houses enduring bad landlords, no rights, high rents and insecure tenancy. But, instead of feeling defeated by the unfairness of it all, she resolved to find a way to make it more equitable.

She met Dan at a sustainability conference. Dan, an architecture graduate, and Nicola, a children’s therapist, bonded over their dedication to the environment. Their plans for the Open Field Co-Living Homestead took shape as their love affair blossomed. For them, sustainability is not restricted to solar panels and hempcrete, but has to exist on a fundamentally human level – as a model for co-habiting, sharing ideas and workloads such as child-rearing, cooking and gardening.

The couple’s unfinished hempcrete bungalow looks like a Viking longhouse. Dan has designed each element of the homestead in painstaking detail to conserve energy, minimise noise and have the feel of a home. It will have eight bedrooms, a massive common room and central kitchen, plus a mudroom and a guest room with bathrooms at each end. The deeper experiment – how to foster community in a shared house – has also begun … at least in theory.

The search for ‘utopia’

Australia has a continuous, largely untold record of utopian experiments, stretching from worker cooperatives and artist colonies in the 19th century, to the hippie communes of late 20th century, to today. The commune timeline tells stories of hopeful individuals – some inspired, some deluded – all joining together and striving toward something better than the status quo.

Dr William ‘Bill’ Metcalf, from The University of Queensland (UQ), is Australia’s foremost expert on intentional communities. He does not buy into the notion of utopia as a noun – a thing that exists – but says there is a descriptive “utopian ideal” of improving and moving towards perfection in intentional communities. The word ‘utopia’ is a Greek pun that means both “no place” (ou-topos) – a place that doesn’t exist – and “good place” (eu-topos). English philosopher Thomas More coined the word and used it for the title of his 1516 book about an island where the citizens lived in harmony adhering to the highest principles.

Bill’s interest in intentional communities grew out of his experience growing up in rural Scotland where farmers regularly joined together on working bees. When he moved to Australia, he and his girlfriend gravitated to share houses, mostly for the cheap rent. He was doing his master’s degree in sociology at UQ in 1973 when the Aquarius Festival was held across the border in Nimbin, northern New South Wales. That 10-day “survival” festival made a big impression on him. “The openness, the sexual freedom and the sense of camaraderie were really strong,” he explains. Since then, he’s visited and re-visited scores of communities around Australia for his research. Bill is an erudite, pragmatic academic who’s been living the ‘community’ approach his entire adult life and says it would be hard to live any other way.

Communes sprout ‘like magic mushrooms’

The Tuntable Valley in northern NSW has steep hillsides clothed in ancient Gondwanan rainforest, some of the last remnants of intact subtropical rainforest left on the planet. This valley is also home to the Tuntable Falls Coordination Cooperative, an intentional community established in the 1970s.

Megan James is one of its founding members. The 76-year-old emerges from her caravan on a Sunday morning at dawn, ready to get the digger in gear and reclaim some of the land she lost during a landslip in the 2022 floods. “We’re affected by all the horrendous overregulation, climate change, wars and disaster and all the rest of it. But to have that sense of community is immeasurably valuable and totally worth working for,” she says. “Once you’re part of a community, you’re always part of that community. You come home, and it’s always home and I think that’s fantastically empowering for people in our culture.”

Megan arrived at Tuntable 50 years ago in a Kombi van with a baby in her arms and big dreams of creating a new life for herself with like-minded individuals. These dreams were interrupted by a once-in-a-lifetime flood in 1974, that destroyed her car home – but not her pioneer spirit.

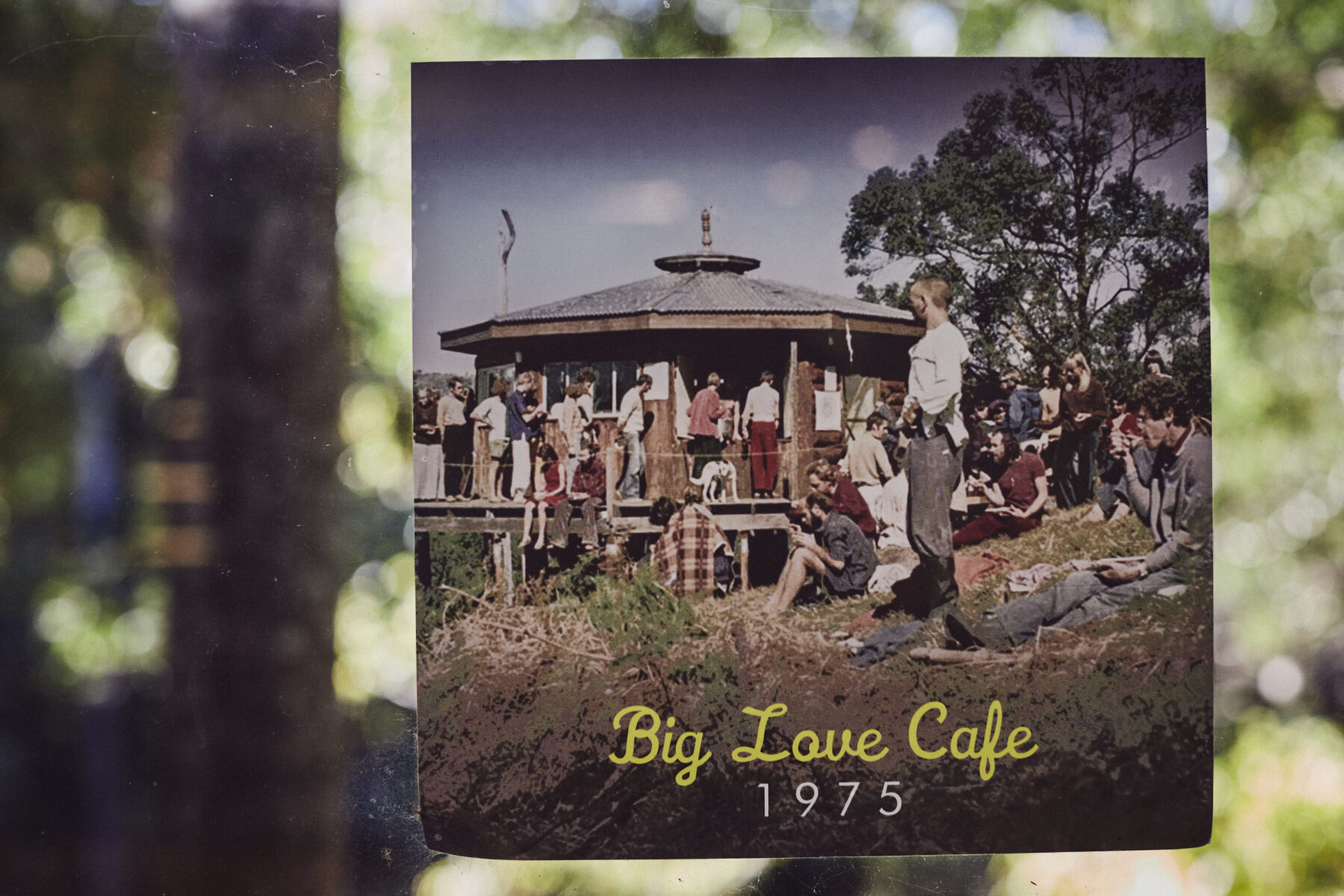

Tuntable was born out of the aspirations of the 1973 Aquarius Festival that Bill Metcalf also attended. After the festival, 40 pioneers each paid $200 for a share in the Tuntable Falls Coordination Cooperative, 200 acres (81ha) of pristine rainforest and depleted dairy pastureland at the dead end of a steep mountain valley. They were hoping to create a new society, and Tuntable seemed like perfect utopian material.

These were the movers and shakers of the intentional community movement; a bunch of urban hippies who survived by speed-learning life skills, pooling physical and intellectual resources, petitioning to change state planning laws and establish new codes for housing sustainability. It resulted in 168 intentional communities flourishing today in NSW’s Northern Rivers region.

For 50 years, government resistance, internal fighting, drugs and drug raids, deaths, births and natural disasters haven’t managed to break Tuntable. It’s the ultimate survivor, a wild garden of humans and plants re-seeding and regenerating. “We have the power of anarchy here – a very interesting dynamic to live with,” Megan says.

Hippie rejection of authority and structure shaped the commune but also tested the limits of consensus-based decisions. In the early days the community had stated rules, such as “No heroin”, which was scrapped in the 2000s and replaced with “No chemical drugs’’. But today, even that rule has been scrapped. “It’s unenforceable,” Megan says. “In the early years, we also had a ‘grievance person’ but that’s a thankless role in a community of over 400, so that role is moribund. The only rule that has endured is not using power tools on a Sunday.”

While it lacks foundational ideology, Tuntable has an asset that has aided its long life. In the early days, a group of young mothers, including Megan, built a pre-school and, not long afterwards, the Tuntable Primary School, which today services all families in the area, not just those in the commune. Kids who’ve gone through that school or grown up as wildlings in this pristine rainforest valley experience some magic that, years down the line, brings them back to Tuntable to raise their own children here.

Communes sprouted like magic mushrooms across the Northern Rivers region in the 1970s. Those communes with strong value systems, such as Bodhi Farm, Dharmananda and Siddha House Farm, survive today. The clarity of those ancient religious precepts of “do no harm” and “maintain equilibrium” has helped participants manage the personal issues that plague community living.

“We were hippies and we believed in the perfectibility of humankind,” says John Seed, one of the founding members of Bodhi Farm, established down the valley from Tuntable in 1976.

Spiritual refuge

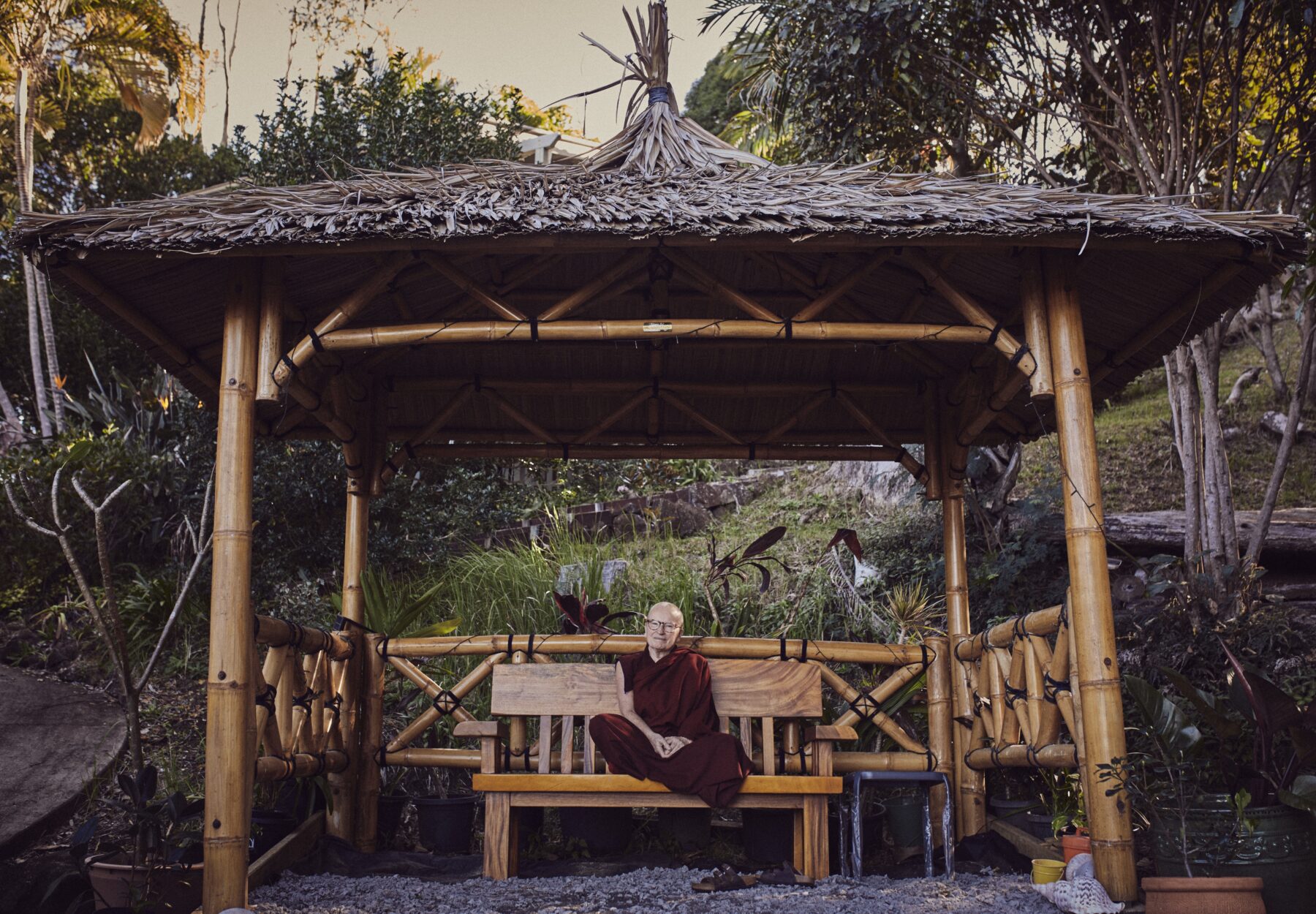

In 1974, four travellers returned from the Hippie Trail (an overland journey spanning from Europe through Southeast Asia) and bought land in southern Queensland with a plan to start a spiritual commune. A couple of months later, the new owners were at a meditation retreat held by two visiting Tibetan monks and invited them to see the property. On that first visit, the Chenrezig Institute was conceived. The monks were ambitious; they envisioned a Buddhist sangha (community) with a gompa (a sacred teaching site), as its heart.

Chenrezig expanded during the late 70s and 80s, becoming a refuge for young people curious about Buddhism who were seeking a deeper experience. Today, with a new rinpoche (spiritual teacher) and plans for a grandiose stupa, Chenrezig continues to evolve. Venerable Ailsa Cameron, one of the community of nuns who lives on the property, donned a tool belt in the early years and worked alongside the men to build the community to what it is today.

Yet, even with her strong guidance in Buddhist principles, she still needs to navigate personality issues with community members. “There are always going to be people you cannot agree with,” Ailsa says. “But they are the ones who present the opportunity to practise.”

Colin Crosbie, one of the original owners, agrees. “You come across all sorts of situations – especially because of my Scottish heritage I want to tell them, ‘Pull your head in’,” he says. “Your patience and compassion and respect for others is on the line daily.”

Chenrezig survives as a community because it adapts. The hippie support of early years has waned, replaced with the interests of new immigrant communities from Bhutan and Nepal. It’s on their pilgrimage trail.

On his 2011 visit to Australia, the Dalai Lama visited Chenrezig and consecrated the Garden of Enlightenment as a place for contemplation and a resting place for the ashes of loved ones. The eight stupas on site depict the eight great deeds of Buddha’s life. The statues are crafted on site by Jim Stint and funds from the sale of these support Chenrezig. Most people purchasing a place for the ashes of their loved ones or pets are not Buddhist. Jim, aged 77 and “from the coast”, has purchased a burial plan at Chenrezig: “It’s so peaceful here,” he says and points to his daughter, Paula. “She will always love to come and visit after I’m gone – spend a day, be happy.”

The modern ecovillage

The modern ecovillage movement is the direct descendant of the 1970s commune movement in Australia. But, in contrast to earlier hippie versions, governments are back in the picture, supporting projects with the milder communal model of shared, low-impact infrastructure and sustainability principles that large-scale contemporary eco-developments propose.

There’s also a shift in structure away from shared ideology as the basis of community towards shared spaces and away from co-ownership, to private ownership of houses. On the Central Coast of NSW, approval has been secured to expand the sustainable-living inspired Narara Ecovillage to 300 houses. John Seed, originally from Bodhi Farm, bought a house in Narara as a retirement plan to be closer to his children. He says he never imagined living in a “bourgeois” development like Narara. He was surprised by its community spirit.

In a similar vein, the aptly named Ecovillage in the Currumbin Valley provides sustainable living for the well-heeled on the Gold Coast in Queensland. In this multi award-winning environmental paradise, some of the 140 houses each sell for more than $2 million.

A roller-coaster descent into the Mary Valley, west of Maleny in the Sunshine Coast hinterland, is the shining star of the Australian eco community movement: Crystal Waters Eco Village. It’s the first of its kind in the world. It’s a village because it has shops, including a café, bakery and monthly market, plus 83 half-hectare plots clustered around man-made lakes and forest and populated by 250 residents and mobs of very relaxed, well-fed eastern grey kangaroos.

“The idea of permaculture is not to go into nature and live a natural life, but to take areas that are degraded and bring them back to life. It’s a regenerative approach,” says Morag Gamble, a Crystal Waters resident, who’s made her home and career in the permaculture world. Crystal Waters perfectly expresses this ethos. When Morag arrived here 30 years ago, it was a paddock. Now, 50 per cent of the 260ha development is regenerating forest – green sanctuaries that encircle the residential areas and connect to the lovely Mary River that snakes through the centre of the property.

For Morag and her family there is also the bonus of safety and security for her children, who roam free through this landscape. “We know all the neighbours and we know they are being looked out for,” she says. Growing up here means her two children have strong ecological awareness. “Whether they know it or not, they will take that with them through life,” Morag says.

It sounds ideal – utopian, even – and yet there is one factor that can bring down an entire community as effectively as clear-felling a forest: personal disagreement. One aggrieved member can finish a community by wearing down committees and depleting resources of goodwill.

Jason Hilder, a former resident of Crystal Waters and ambassador for the Global Ecovillage Network, scores the Crystal Waters community poorly on social cohesion, and says advocating for change within the community had a big effect on his confidence and mental health. “Eighty-six lot holders each have a say and [making] a decision can take a really long time,” Jason says. “There’s also significant difference between people who are compatible and proactive around a philosophy.”

Canadian novelist and poet Margaret Atwood, author of The Handmaid’s Tale, believes the question facing those seeking alternatives to mass society is, “What sort of happiness is on offer and what is the price we pay to achieve it?” The housing crisis and fears for survival are bringing intentional communities into the mainstream it has eschewed for centuries, transforming the model into a blueprint for the planet’s future. People want to escape the utter loneliness that can pervade society and do it in a sustainable, sharing, caring, eco-friendly way. The biggest drawback remains the most fundamental: living with thy neighbour.

‘Faerieland 2.0’

The radical faeries have been experimenting with different ingredients for the magic pudding of harmonious communal co-existence for decades. They have a long backstory, but essentially the movement took shape on the US West Coast in the 1960s and 70s through gay-rights activist and communist Harry Hay. A lot of gay men in San Fransisco at the time did not feel represented in the movement.

Harry became interested in Native American rituals and how he could use them to forge a gay social tribe. He held gay “gatherings”, away from cities in New Mexico and Southern California, where participants could be free to explore a more spiritual side of gay liberation, working with methods he called Heart Circles to help unshackle gay men from doubt and self-hatred.

Historian Ian ‘Teacosy’ Gray visited the original Faerie sanctuary at Short Mountain in Tennessee in 1980 and returned to Australia with a vision to create one here. After a few false starts, he and some friends established Australia’s only Faerie sanctuary on 53ha of rainforest and pastureland west of Nimbin – a spectacular piece of land with an old farmhouse occupying the high ground at its centre.

The sage green timber house has a wide, covered verandah that overlooks the green striations of the Great Dividing Range to the north and west. This site has been home to successive waves of resident Faeries and visitors who, until recently, all slept and shared meals in the house.

For members of the community, Faerieland is not merely a roof over their heads or cheap accommodation, although residents only pay a modest weekly stipend to live there. It’s a refuge where the work of personal and interpersonal transformation can go very deep. After 22 years, Teacosy no longer lives at Faerieland but remains an elder, mentoring the next generation of Radical Faeries in what he and the other residents are calling “Faerieland 2.0”.

Faerieland is unique because it is structured around stewardship, not ownership, of the remnant rainforest. Slowly over the years, residents have attacked the lantana weeds strangling young rainforest saplings and given it breathing space. Radical Faeries hold a neo-pagan view that we are interconnected and nature is sacred. Faerieland 2.0 is shaping up to be more inclusive, expanding from supporting gay men in their journey to wholeness to include neurodiverse and non-binary people. “We are all stewards and offer something to the community project,” says long-time Faerieland resident Spryte.

The work on building community is ongoing. Teacosy believes that the core value of community is not fitting in, but finding a place where you feel safe, where you can take care of yourself and others, and feel seen. Hosting a ‘Heart Circle’ is a Radical Faerie tradition that helps foster community.

During a Heart Circle, Faeries get to share what they feel while others in the circle listen with respect and love. “I’ve seen some of these go on for days,” says Razr, who arrived in February 2022 when Faerieland 2.0 began. “We walked into a fully functional community. Some people just need more structure, others don’t, that’s what we are negotiating now.”

“People arrive and tell us they’re running away from something,” Teacosy adds. “Instead, we encourage them to tell us what they are running towards … what they have to offer.”

Spryte moved here from the NSW South Coast, where he ran a successful Pilates studio catering to older gay retirees from the city. “They wanted a certain kind of country life, but I always wanted something more … alternative. And then, you find your tribe and go, ‘Oh, now I make sense’.”

The Faeries have a sacred drag shed on the property where they transform. “Drag brings us together,” Razr says. “The idea is that we take clothing and remove the gender attachment to it.”

Razr, who came from the gay scene in San Francisco, is dressed for a community working bee in an elegant black outfit with a large-brimmed hat and netting. Spryte collects a machete and chats to Sphere, who’s wearing a 2m-long python around his neck.

Razr chats to Orca, the youngest resident of Faerieland, as they head out with the others to cut a path through summer undergrowth to the creek below.

“It’s not easy living in community. Part of being here is dedicating a certain percentage of your time making sanctuary, whether that be environmental, cultural or relationship,” Razr says. “And we try to value our relationships as much as we value our mission.”

Affordable living

Every intentional community in Australia is unique. Where Faerieland is fluid and changing, Murundaka Cohousing Community in Melbourne’s outer suburbs is a highly structured urban oasis. The product of enlightened state planners in the 1980s, co-housing – targeted towards low-income renters – is flourishing in Victoria’s cities.

“People increasingly want to live rich lives without spending millions of dollars,” says Giselle Wilkinson, who founded the Murundaka Cohousing Community in 2011.

On a grey Friday afternoon, three cooks are chopping veggies in the common room, while a fourth is picking flowers from the garden to place on the four communal tables. There is a small library, a few couches and whiteboards close to the open kitchen that announce upcoming committee meetings for gardening, cooking, wellbeing and finance.

Mikoto, a founding member of the community, is head chef for tonight’s communal meal of sushi rolls. A quiet young man called Sonal is helping her. He grew up in Melbourne and recently moved back after living in France. His partner speaks little English so he decided Murundaka would be a soft landing for her – adjusting to a new country without the support of a tight community would be too hard.

Every resident here is an owner of sorts, with a $1 share in the company. By signing up, you agree to the Murundaka Code of Conduct and responsibilities, such as committee work and helping make communal dinners. The residents share washing machines, tools and maintenance duties. Some people neglect the Friday night dinners and Mikoto is disapproving: “Everybody is juggling … but if you don’t come for the common meal once a week, why are you living here?”

The community faces in, with the common room, garden and courtyard at its centre. In a community enveloped by suburbia, the world outside becomes the ‘other’. Mikoto waves a dismissive hand to the street: “Outside of here it is all nuclear families,” she says. “I’m still embracing this place. I love it.”

The 35 residents range from infants to pensioners. Murundaka’s mission is to provide secure housing for people who cannot afford high rents. Once your income reaches a certain level, you leave and make way for other residents.

Co-housing resident Fleassy lives here with her daughter and partner Rory. “Yes, this is affordable housing but what the community gives you is actually affordable living,” Fleassy says. “For a single parent it makes a huge difference in quality of life you can offer a child – mentally, emotionally and financially.”

Articulate and cheeky 10-year-old Amalie, the daughter of Alex and Emma, has grown up in the community. She sums up the dynamic perfectly: “We’re more like family than friends. We fight like family and we celebrate like family.” Another resident, Rachel, agrees. “Living in community is a lot!” she says. “It’s a revolving door with the kids, like living and working in a big fish-and-chips shop, but the support of the other parents is priceless.”

Like an extended family, the whole community travels away from the city every year for a five-day retreat – a family holiday, but with more purpose. They hang out together, hone their communication skills and practise the Thomas-Kilmann method of conflict resolution to remove the build-up of relationship plaque from the communal harmony.

Walking the talk

Professor Samuel Alexander, lecturer and researcher at The University of Melbourne and co-director of the Simplicity Institute, is someone who has advocated for intentional communities to adopt a more hardcore approach to sustainability. He believes intentional communities should be prioritising the climate crisis, not lifestyle retreats.

Samuel’s 2013 novel Entropia envisaged a utopian society on an island in the South Pacific after a climate armageddon. Inspired by the novel, a family offered him 8ha of land in Gippsland, Victoria, to create a utopian community. Sam got to work planning and building a display village for future survival and called it Wurruk’an – meaning “to seed a new Earth story”. The experiment attracted ecowarriors, hardcore environmentalists, including a young Dan Prochazka, with the aim of reducing their ecological footprint to near zero. They used the motto “Radical Simplicity” to describe their lifestyle. It was hard, rewarding work, a call to arms for ecowarriors to walk the talk.

“That was an attempt to radicalise and politicise the ecovillage movement to whatever extent we could,” Dan says. Dan was a true believer, acting on the realisation that single family living arrangements are unsustainable and take up too many resources. The experience at Wurruk’an confirmed for him that more people have the capacity to live under the same roof than currently do.

“There’s a middle-class affluence that can underpin many ecovillage experiments,” Samuel says. “They might be lovely people with good values wanting to live a simpler life but they are also escapists; middle-class people leaving the horrible city and buying land elsewhere, living a lovely peaceful life, growing their own food. Their environmental footprint is still outsized.”

According to Samuel, there’s also a deep ignorance about what living in community involves: we believe we know how to do it, but we don’t – we need education. He says there are entrenched behavioural patterns born out of our “disposable” social world and the infrastructure of private housing; we avoid irritation, we walk away, leave the city or our job when somebody or something bothers us.

People don’t get a choice about which family they are born into, but living in community is a conscious decision. At the very least, it should involve developing a knowledge of available tools and techniques, like the Radical Faeries’ Heart Circles, and an understanding of non-violent communication to aid members to live together in harmony and productively.

American naturalist and essayist Henry David Thoreau wrote that “a man is rich in proportion to the number of things he can afford to let alone”. On so many levels, living in community is hard work, yet the shared nature of it simplifies, diversifies and lessens the load.

“It’s a real magic feeling when you feel everyone’s putting their energies towards a good cause,” Dan says. “Trying to have as much as possible of that in our lives is the dream.”

Dan and Nicola’s Open Field Homestead is up and running. The common dinners are a huge success. The 10 residents eat together six nights a week, which ticks one of Bill Metcalf’s rules for a successful community. There have been a few tensions between certain individuals but so far they’ve all been resolved amicably. There seems to be a real motivation to positively resolve disputes and maintain relationships.

The aspect that spans all intentional communities is the value of working together to create a shared vision, whether it’s planting forests or making schools. The dominant ethos is about leaving things better than you found them. At Chenrezig, former road manager and current director Steve Alberts calls it “serious history”. “We’re making stuff for millennia,” he says. “People come and go, but what we leave will be here long after we are not even a memory in people’s minds.”