The red face, black beard and gold-trimmed blue robes of the Chinese god Guan Di make an exotic splash in the corner of a quiet country pub in North East Tasmania, far from their origins. Protected by a glass display case, the porcelain statue may go unnoticed by most patrons at the Weldborough Hotel, but it’s an important reminder of a time when Chinese migrants outnumbered Europeans in this part of the island state.

The contribution of Chinese migrants and their descendants from the 1880s through to today is celebrated in Home: Here and Now, which recently finished its run at the Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery (TMAG) in Hobart. The exhibition, which will next tour the state’s north-east, reveals a chapter of Tasmania’s history that’s often overlooked.

Chinese settlement in Tasmania began in the 1830s with the arrival of nine Chinese carpenters. During the next two centuries they were followed by miners, market gardeners, restaurateurs, students and entrepreneurs. In the 2021 census, 12,300 people in Tasmania – about 2 per cent of the state’s population – reported having Chinese ancestry.

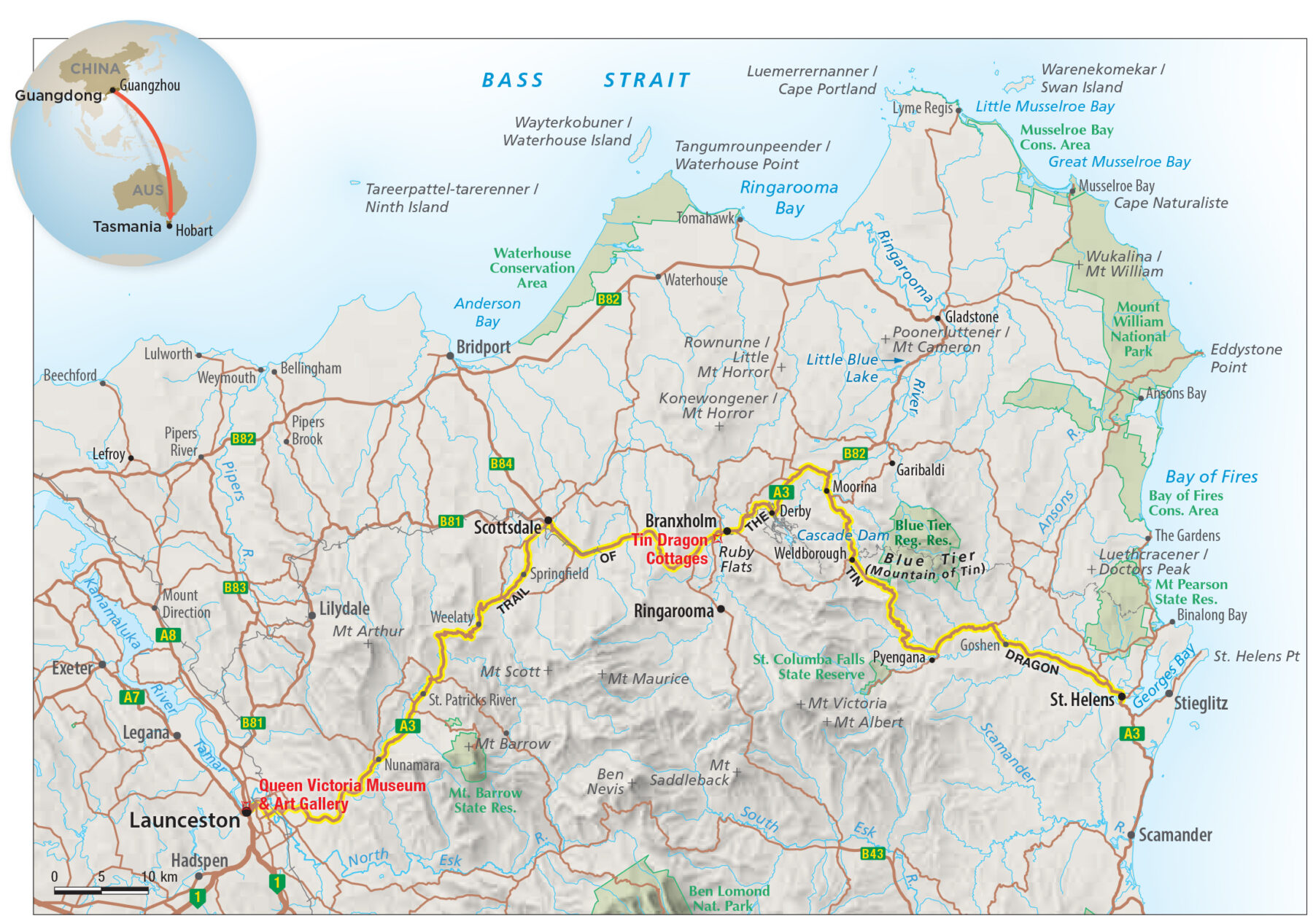

Although some Chinese came to Australia in search of gold, others were lured by tin to Tasmania. During the tin-mining boom of the 1870s and ’80s, when there were 40 Chinese-owned tin-mining leases operating, Tassie’s Chinese population of 1500 (1.3 per cent of the then-total population) mostly lived in the rural north-east. Almost all came from China’s Guangdong Province.

The centrepiece of the Home: Here and Now exhibition is a display of items from the Guan Di Temple, built in Weldborough in the late 1800s and now housed in the Queen Victoria Art Gallery at Royal Park in Launceston. Guan Di (also known as Kwan Ti), a Taoist god of war and Buddhist protector, represents loyalty, righteousness, justice and humility, as well as literature and learning. Worshipped for his ability to cast out demons and prevent war, Guan Di embodied qualities important to Tasmania’s early Chinese communities.

The temple has artefacts from several north-east temples, which over the years – as mines closed and tin-mining settlements were abandoned – found their way to the temple at Weldborough. Temples were known to have also existed at Garibaldi, Moorina, Gladstone, Branxholm and Lefroy. In 1934 the Weldborough temple – a small wooden building with a tin roof and a portico at the front – closed, and the museum became its custodian at the request of the Chinese community.

Personal artefacts loaned by fourth-generation descendants of Chinese tin miners to the Home: Here and Now exhibition play an important role in telling the story of what it means to belong to a community far removed from their ancestors’ experience. One of the people interviewed for the exhibition was Brian Chung, who was born in Guangzhou and moved to Hobart when he was eight years old. His forebears have migrated between China and Tasmania since 1887 and ran a market garden for decades. Brian loaned the exhibition a bamboo tray that his ancestors used in their market gardens.

“It’s really through their personal experiences that belonging in Tasmania can be better understood,” says Isobel Andrewartha, senior curator of cultural heritage at TMAG. “We spoke to recent migrants too, with seven people contributing oral histories, talking about very different experiences but with similar narratives.

“Temples were an important part of the community. The Europeans called them ‘joss houses’, but Guan Di represented supportive brotherhood, loyalty and resilience for the workers. And even though the Guan Di Temple is now housed in the museum in Launceston, it’s still a working temple.”

The interiors of Chinese temples were decorated with colourful banners, red flags, silk scrolls, wood carvings and plaques bearing texts, including passages from The Analects by Confucius. In the Guan Di Temple, a gold plaque reads: “The love of brotherhood is heavier than a mountain and deeper than a river.”

Trail of the Tin Dragon

The stories of North East Tasmania’s Chinese migrants can be explored on the Trail of the Tin Dragon, a themed heritage trail that celebrates their history and contributions to the region’s development.

The first stop is Branxholm, about 90km from Launceston. In 1877 the town’s bridge was the site of a violent confrontation between Chinese and European miners. The infamous incident was sparked by the belief among Europeans that the Chinese – who often worked on ‘tribute’ (a fixed rate) for mine owners, accepting lower pay – were stealing their jobs. In parts of North East Tasmania, Chinese tin miners outnumbered their European counterparts by 10 to one.

During the confrontation, European miners attacked Chinese workers attempting to cross the bridge to the tin mines at Ruby Flats. The incident came to be known as the ‘Showdown on Branxholm Bridge’.

At the top of the hill overlooking Branxholm, a sign tells the story of the merchant and mining lease owner Ah Moy, who is buried at Branxholm Cemetery.

A bush track beside Branxholm’s Ringarooma River leads to Tin Dragon Cottages, an eco-friendly tourist accommodation run by Christine Booth and Graham Cashion, who built the stone and timber cottages 20 years ago.

“We have a unique Chinese history in this area and we discovered there had been a number of former tin-mining leases on our land. We worked with the descendants of the miners to research the history, and they were delighted to help,” Christine says.

Tin Dragon Cottages’ five self-contained cottages are named for Chinese miners – Ah Moy, Ah Ping, Chintock, Fon Hock and Ah Back. Visitors can walk through bushland of myrtle, sassafras, eucalypts and Tasmanian tree ferns on what was once the alluvial tin-mining lease of Henry Ah Ping. Christine and Graham commissioned Tasmanian sculptor Folko Kooper to create silhouette tin sculptures of Chinese miners to add interest to the walk and tell the miners’ story. Pademelons bound past, and a tailrace carries water as it would have in the mine’s heyday.

In nearby Derby, the streets are still lined with miners’ cottages. These days, the town’s main attraction is the network of mountain bike trails that crisscross the Blue Tier plateau. Now covered in regenerated bush, the Blue Tier was once known as the ‘Mountain of Tin’.

A stop at the Derby Schoolhouse Museum yields more stories of the town’s history, including the 1929 deluge that burst the banks of the Briseis Dam. The disastrous incident flooded the mine and parts of the town, killing 14 people.

North of Derby, just off the B82 to Gladstone, is Little Blue Lake, a former mining pit that glows a vivid turquoise from the heavy minerals still in the soil beneath the lake. Spectacular as it is, the lake is unsafe for swimming due to its high mineral content – but it’s a magnet for photographers.

Tracking south, we cross the Ringarooma River to Moorina. In Moorina Cemetery is a memorial erected by the Chinese community to the Chinese migrants who are buried there. Next to the memorial stands a restored funerary oven, where paper prayers and gifts were burnt as offerings for the deceased.

A sign in the cemetery explains the culture clash between Chinese migrants and Europeans who tried to “Christianise” the “heathens” and the reasons why the European graves all face east while the Chinese graves face west. The sign also explains the intriguing ritual of the second burial, where many of those who died in Tasmania were later re-buried in China.

Ruby Lee, who contributed to the Home: Here and Now exhibition’s oral histories, explains the Chinese traditions observed in the Qingming Festival. “It’s a once-a-year thing called ‘grave-sweeping’,” she says. “You go to the cemetery, and you have your ancestor worship. You thank your ancestors for everything that you have. So, when you go there, there’s all these foods; you’ve got roast pork, chicken, you’ve got some oranges, eggs. You put it all out, you burn the incense.”

Weldborough Cemetery also has a Chinese memorial and burner and a handful of marked Chinese graves. The Tasmanian Heritage Council describes the burner as “evidence of Chinese burial practices as they were carried out in Australia and the adaptations made to new conditions” and describes the cemetery as “one of the few prominent surviving cultural markers within the landscape”.

At the Weldborough Hotel, patrons enjoying a pub lunch may give a cursory glance at the red stone lions and ‘temple dogs’ guarding the entrance. There are only two other indicators that, in 1881, this was a thriving township of 765 Chinese migrants: a poster above the pub’s coffee machine advertising a “gigantic Chinese carnival” in Launceston in February 1891 – around the time of Chinese New Year – and the porcelain figure of Guan Di, a gift from the Chinese government in 1977.

Our last stop on the Trail of the Tin Dragon is the St Helens History Room, where visitors can watch a short film based on the story of former foreign correspondent and ABC journalist Helene Chung Martin’s grandfather Gin, as told in her biography Ching Chong China Girl. Helene is also among those interviewed for the TMAG exhibition, relating her “excruciating” experience of growing up in 1950s Hobart, where she says her Chinese family were stared at as if they were “freaks in a circus tent”.

Links to the past

In 1887, in the lead-up to Federation, calls were made to restrict Chinese immigration. Tasmania was the only dissenting colony, but fell into line with policies that were the forerunners to the White Australia policy, introduced in 1901 as one of the first acts of the new Federal Parliament. As the tin mines ceased to be profitable, the Chinese population in Tasmania dropped. By 1915 there were only about 30 Chinese living in the state’s north-east. By 1921 only 234 Chinese people remained in the state, most living in Hobart and Launceston. Many of the miners, known as ‘celestial sojourners’, never intended to make Australia their home; they were simply working to make their fortune and then return to their families in China.

Recent migration and a generational cultural connection to their Chinese heritage among descendants of the tin miners has helped maintain the links to the past, says Isobel. People from all across China now visit as tourists, and Tasmania has had a strong sister-state relationship with Fujian Province, on China’s south-east coast, since the early 1980s, exchanging both cultural and economic delegations.

Isobel says the Home: Here and Now exhibition, supported by a grant from the National Foundation for Australia-China Relations, wouldn’t have been possible without assistance from the Chinese Community Association.

Lee Mylne and Pia Johnson travelled with assistance from Tourism Tasmania.