Defining Moments in Australian History: The Federation drought

The Federation drought affected almost all of Australia and is widely considered the most destructive in our recorded history, based on the huge stock losses it caused. So named because it coincided with Australia’s Federation, the drought ended squatter-dominated pastoralism in New South Wales and Queensland.

By the end of the 1840s, about 280,000sq.km – almost all of eastern Australia – was occupied by at least 2000 squatters on Crown land.

To control them and encourage closer settlement, the eastern states introduced land reforms in the 1860s, hoping to break up large runs into smaller blocks for farming and grazing. This was not always achieved because squatters found ways to hold on to productive country. Nevertheless, many selectors took up ‘homestead’ blocks, in north-west Victoria’s Mallee district in the 1870s, and from 1884 in the Western Division of NSW.

Meanwhile, expanding railways were enabling agricultural development, particularly wheat growing. Bores were sunk to access underground water, allowing stations to expand further into the semi-arid interior of NSW and central Queensland. At this time, most pastoralists carried high stock numbers, even in low rainfall areas. Sheep were cheap, water was available and graziers had saltbush and other scrub to provide quality feed when overgrazing destroyed perennial grasses.

Rabbits had been introduced to Victoria in 1859 and by the time drought set in they had reached plague proportions across most of south-eastern Australia. They dug up the roots of native bushes and ringbarked trees and shrubs. Between the rabbits, overstocking and drought, pastoralists had nothing left to feed livestock.

With ground cover gone, exposed topsoil was lifted in huge dust storms, a feature of most droughts in Australia.

In 1892 the country had 106 million sheep. By 1903 the national flock had almost halved to 54 million. The nation lost more than 40 per cent of its cattle over the same period.

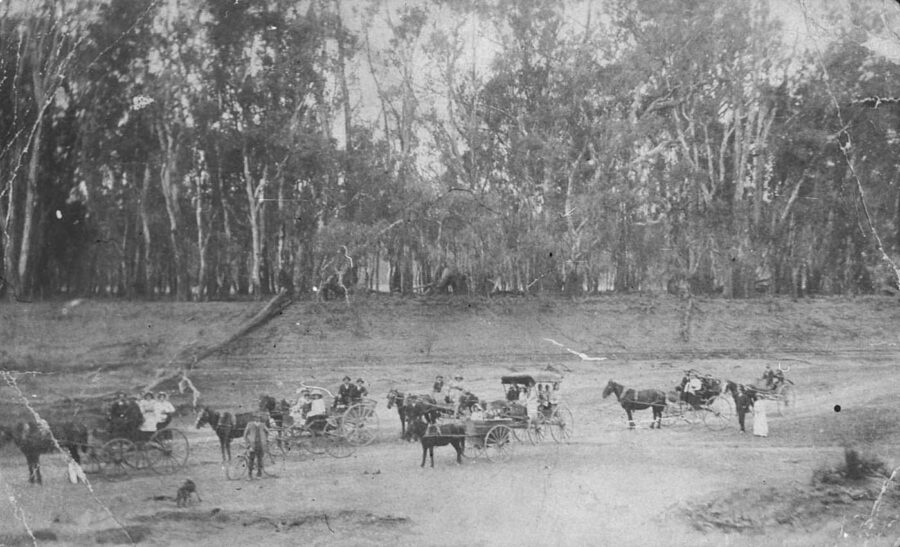

Drovers sought feed for hungry animals along travelling stock routes – the ‘long paddock’ – or moved them to pastures on the east coast and southern mountains with less dire conditions. Droving took an immense toll on sheep and cattle with losses of up to 70 per cent recorded. In 1902 newspapers reported that more than 2000 steers lay dead along Queensland’s Goondiwindi–Miles route.

Pastoralists buckled under mounting costs of buying feed, controlling rabbits and repairing dust storm–damaged infrastructure. And, overwhelmed by debt, many graziers walked off their land. Some 20,000sq.km of leasehold country in the NSW Western Division was reported to have been abandoned between 1891 and 1901.

No state government then had a formal drought-relief policy, and, despite royal commissions and inquiries, they were slow to consider practical measures.The NSW government declared a public holiday on 26 February 1902 for people to“unite in humiliation and prayer” for the end of the drought.

Government offices and most businesses closed and religious services were held. The new federal government refused to reduce duties on fodder or provide other assistance. Drought relief was seen as a state responsibility, which didn’t change until 1939 when the Commonwealth assisted Tasmania to recover from bushfires during another severe drought.

In October 1902 Melbourne’s Lord Mayor opened a public appeal for Victoria’s drought-affected areas and within a year attracted almost £19,000 ($2.7 million today) and helped 1670 families. Sydney’s Lord Mayor began a relief fund in January 1903 that collected just over

£23,000 ($3.3 million) in a year.

In the 1880s, many individual stations in NSW and Queensland were up to 3000sq.km and carried hundreds of thousands of merino sheep. By the drought’s end, many huge stations had been resumed or foreclosed by banks, and, under further land reforms aimed at encouraging closer settlement and the development of agriculture, were partitioned and opened up to selectors.

Smaller properties and sheep flocks became the norm and mixed farming was widely adopted. It would be another 50 years before the national flock recovered to pre-Federation Drought numbers.

‘The Federation drought’ forms part of the National Museum of Australia’s Defining Moments in Australian History project.