Defining Moments in Australian History: the Petrov affair

This Cold War saga and the information the couple passed to local authorities had global implications, identifying spy networks around the world and affecting Australia’s political balance of power for decades.

An intense post-World War II rivalry between the USA and its allies (including Australia), and the Soviet Union and its satellite states, the Cold War pitted democratic capitalism against single-party communism.

Much of the world aligned with either side. Small wars were fought around the globe and major powers stockpiled armaments, including nuclear weapons, anticipating a large-scale conflict. Spying was key for both sides to gain intelligence on enemy military and economic capabilities and social and political stability.

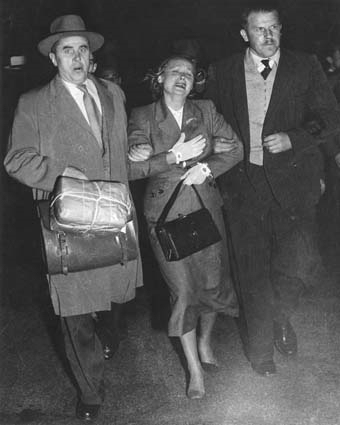

Image credit: courtesy National Archives of Australia

The Petrovs arrived in Australia in 1951 as Canberra Soviet embassy ‘diplomats’. But each had spent years in Soviet intelligence and state security organisations. Vladimir was a lieutenant colonel and Evdokia a captain with the KGB, the Soviet secret service. He was responsible for decoding instructions from Moscow and setting up a Soviet spy ring in Australia. She performed code and cypher work.

In the political chaos after Soviet dictator Joseph Stalin’s March 1953 death, secret police chief Lavrentiy Beria, a close Stalin ally, was arrested and executed. Seen as Beria supporters, the Petrovs’ and their performance, especially Vladimir’s failure to set up an Australian spy network, was questioned by Moscow. This meant the Petrovs risked jail or even execution if they returned to the Soviet Union.

The Australian Security Intelligence Organisation (ASIO) assigned Polish émigré Dr Michael Bialoguski to befriend Vladimir and encourage his defection and the two men spent much time together in Sydney’s Kings Cross bars. In early 1954, Vladimir decided to defect but didn’t tell his wife.

He contacted ASIO through Bialoguski, and Deputy Director Ron Richards spent weeks negotiating the move, especially secret papers Vladimir would bring with him. He defected on 3 April and was taken to a Sydney north shore safe house. Nine days later, just before Parliament rose for the 1954 election, prime minister Menzies announced the defection and called for a royal commission into Soviet espionage in Australia.

On learning of the defection, the Soviets accused Australia’s government of kidnapping Vladimir and placed Evdokia under house arrest in their Canberra embassy. Couriers from Moscow arrived by mid-April 1954 to escort Evdokia back to the Soviet Union.

But news of her return spread through Australia’s anti-communist eastern European community and hundreds protested her forced removal at Sydney Airport.When the crowd saw Evdokia being led away, it surged to try to rescue her. Eventually, she and her guards boarded the plane. But ASIO radioed the pilot and arranged for agents to contact Evdokia at a fuel-stop in Darwin, where she was physically separated from her escorts and asked if she wanted to stay. She was conflicted because staying would place her family in Russia in danger.

After speaking to Vladimir by phone and, just before the plane took off, she decided to stay.

In the 1954 federal election, the Labor Party won the majority of votes but not a majority of seats. Three of Labor leader H.V. Evatt’s staff were named in the Petrov papers as Soviet information sources. Evatt was convinced the Menzies government had orchestrated the defection and planted incriminating evidence in the papers for political gain.

He took his case before the Royal Commission where he made a series of extraordinary outbursts. As a result, the commissioners withdrew Evatt’s leave to appear before the inquiry.

The election loss, differing attitudes to communism and the tension generated by Evatt’s conspiracy theories led, in 1955, to an Australian Labor Party split and the formation of the Democratic Labor Party.This greatly assisted the Liberal/Country Party coalition to remain in power until 1972.

The Petrovs stayed in Australia, were given new identities and lived out quiet lives in suburban Melbourne. Vladimir died in 1991; Evdokia in 2002.

‘The Petrov affair’ forms part of the National Museum of Australia’s Defining Moments in Australian History project.