Fighting for the Snowy River

FROM UP HERE, on the granite blocks of Rams Head North’s peak, in the thinning summer air 2160 m above sea level, the nascent Snowy River looks like the frayed cracker of a well-used stockwhip. A spongy mass of sphagnum laced with streamlets, snowgrass and boulders, the famous river’s birthplace decorates an alpine saddle a few kilometres south of Mt Kosciuszko.

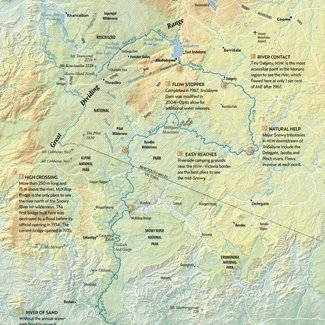

This soft, beautiful eyrie is the start of the Snowy’s 405 km path to the sea and part of the scant 17 km where the mighty river of myth and verse is truly wild. It’s also the margin that divides the catchment of the westward-flowing Murray River and that of the eastward-flowing Snowy catchment. The Murray tributary – the Swampy Plain River – quickly disappears from sight, plunging down the Main Range’s steep western faces. The Snowy stays high and in view, meandering east across the treeless plateau. Turning north-east, the river enters the realm of snow gums and near-impenetrable heath.

The river is just 14.5 km north-east of Rams Head North when its waters back up behind Guthega Dam, the first of four dams created by the Snowy Mountains Hydro-electric Scheme. Guthega Pondage is a perfect metaphor for the Snowy’s modern story, which has little to do with poetic notions of the high country. It’s all about water, who stakes claim to it – and whether the river that provides it gets a say.

River repair theory

It’s tempting to see the Snowy River story as a simple one of goodies and baddies, but nothing’s that easy. In fact, it’s a salutary tale of how perceptions shift over time, shaped by national need and knowledge. Professor Sam Lake, an ecologist at Monash University, Melbourne, has a five-decade association with the river. “I used to go fishing on the Snowy with Dad, back when it was a really wild river,” Sam says. “The Snowy’s lifeblood was a very big flood that used to come down with the snow melt, starting about late-August and going all the way through to November. The high-flow period was a colossal thing. From the timber bridge across the river at old Jindabyne township, you’d see this massive amount of water roaring along and you could see the bottom, 20 feet [6 m] or so below the surface. It was just fantastic.”

These days, such magnificent natural spectacles usually create their own life insurance. But that wasn’t the case when the Snowy hydro scheme was imagined and enthusiastically embraced. In an era of rapid development and of belief in bending nature to civilisation’s need, the hydro scheme was a way to “drought-proof” agricultural lands to the west, and a source of immense national pride. “It was myth-making stuff to a certain extent, coming out of the gloom of the Second World War,” Sam says. “And it was seen as nation building.”

In one of the last big projects of the scheme, in 1967, a dam near Jindabyne was completed, flooding much of the surrounding valley. Together, Jindabyne, Guthega, Island Bend and Eucumbene dams would stop all but one per cent of the Snowy’s headwaters flowing downstream. It was a profound change both for the river and the people who lived near it. Jindabyne had to be moved to higher ground, on the shores of the new lake. For much of its next 70 km, until it’s bolstered by water from the Delegate River, the Snowy crosses the grazing country of the Monaro tableland, which lies in the rain-shadow east of the Snowy Mountains. The water that Monaro graziers and townsfolk were accustomed to was switched off.

Today this seems close to unconscionable. Not so in 1949, when the Snowy scheme was launched, or even the 1960s, when it was nearing completion. All that water flowing out to sea was seen as a waste. But over the years attitudes to conservation changed, and the voices raised on the river’s behalf grew in volume, knowledge and persistence. The 1990s brought the chance for the Snowy’s emancipation. In 1994 the new Council of Australian Governments Water Resources Policy recognised for the first time that the environment was a legitimate water user with definite needs – in other words, that rivers deserve a share of their own water.

Scientific data was needed to support a claim for the Snowy, so catchment managers in NSW and Victoria commissioned an assessment of the river – a novel approach. With nothing to offer but enthusiasm and a “beer and a bed” budget, a young NSW catchment manager named Brett Miners approached six of Australia’s leading river ecology experts, one of whom was Sam Lake. “We all did it pretty quickly – it was about a week on the river late in 1995, then exchanges by email right through Christmas to write the thing,” Sam recalls.

Released in January 1996, the expert panel report called for such things as vegetation management and gave suggested flow ranges it believed would be needed to “switch on” the river’s moribund natural systems. They stipulated that the flows needed to change from season to season to mimic the river’s natural variability. But what interested most people was its minimum-flow recommendations, and river activists calculated a magic number: 28 per cent of its average natural flow was required to maintain the Snowy’s environment. Now all it needed was the water.

LAUNCH GALLERY: High country huts

The big fix

After an hour with Brett, you’re left thinking that rehabilitating a river is no more difficult than any other sizeable undertaking. It’s only when the lanky NSW Southern Rivers Catchment Management Authority landscape manager spreads out maps and charts that the sheer scale of the Snowy rescue sinks in. And Brett’s only responsible for 183 km of the job: there’re another 170 km in Victoria to deal with.

Brett grew up on a Monaro farm during the river’s darkest days and left after school to study natural-resource management. He returned in ’94, as interest grew in the Snowy, and one of his first big decisions was to organise the 1995 expert panel assessment.

After that, it seemed that the process would fast gather momentum. People from Dalgety and Orbost, Victoria – the only towns on the river downstream of Jindabyne – formed the lobby group the Snowy River Alliance, which made “28 per cent” and “let the Snowy flow” the phrases that punctuated five years of negotiations between Snowy spruikers, Murray River irrigators, hydro-electricity managers, scientists and Federal and State governments.

There was despair among conservationists when the 1998 Snowy Water Inquiry announced that no more than 15 per cent could be returned, but it was politics that would settle the debate: the catchments and their water were ‘owned’ by government. In the 1999 Victorian State election, a young Alliance member named Craig Ingram won the seat of Gippsland East as an independent and ultimately helped Steve Bracks form a new government in return for its support of Snowy River flows. After another year of tough talking, environmental flows for the Snowy passed into law in December 2000.

The agreement that outlines how, and how much, of the water will be returned to the river below Jindabyne is complex. Its underlying point is that the Snowy’s extra water was not being taken from irrigation communities; it had to be found in savings from the existing irrigation infrastructure and bought from allocations. It stipulates that increased Snowy flows must have no adverse impacts on irrigators in the Murray, Murrumbidgee and Goulburn-Murray river systems – or on water security or water quality in SA. The agreement names the target Snowy River flow over 10 years as 21 per cent of annual natural flow (ANF), with an extra 7 per cent (a total of 28 per cent) if further irrigation-water savings are found.

Fed by melting snow and glacial-remnant lakes,of Kosciuszko NP, the high-country Snowy is easily accessible

at just a few points, including a point on the Main Range Track near Charlotte Pass. (Photo: Ross Dunstan)

The first environmental-flow release of up to 38 GL came with great fanfare in August 2002, but since then it’s consistently failed to meet targets; drought, intricacies of water infrastructure and entitlements, and the reluctance of stakeholders are cited as reasons. By 2009, the Snowy’s flow below Jindabyne ought to have increased to 15 per cent of ANF. It has never exceeded 5 per cent.

While the flows debate ventures into ever finer and more complicated detail, Brett is on the ground, working to bring the river back to life. “It’s had two big hits,” he tells me. The first was the erosion and sedimentation, which peaked sometime around 1890. He cited a study of the callitris – native cypress – country of the mid-Snowy in Kosciuszko National Park, which indicates that, in the 19th century, the region lost an average of 12 cm, and up to 30 cm, of its top soil to a grazing and burning regime. The second big hit was the removal of the river’s headwaters.

The seasonally variable flow that had shaped the river’s structure, and influenced its plants and animals, disappeared. The absence of an annual snow-melt flood allowed sediment to accumulate, and weeds such as willow and blackberry colonised the permanent sand flats across which the river found a new, shallow, meandering channel. The mighty Snowy shrank to little more than a regulated trickle.

It’s more than a decade since teams in NSW and Victoria started rehabilitation work on the river, removing invasive weeds and reintroducing native species. “The really hard thing is, rivers just do what they want to do anyway,” Brett says. “We don’t try to train the river and say, ‘Look river, you’ve got to settle down, you’re going to have an active channel a third or a quarter of the size that it used to be’.

“So our job is to get as much native riparian vegetation in the bed of the channel and the river will sort itself out.”

Brett’s enthusiasm for saving the river hasn’t waned in more than 16 years, but he’s still rueful about its past. “The Snowy would probably have stayed reasonably healthy if they took 50 per cent of its water,” he says. “The late Professor Peter Cullen, who was a member of the Wentworth Group of Concerned Scientists, had a little rule of thumb. He said you can extract up to about 30 per cent of a river’s water reasonably safely if you do it well. If you extract 30-70 per cent, you have to do it really well or you’ll start to degrade that river system. And once you get over 70 per cent extraction you’re into the red zone – you’re starting to have a substantial, sometimes irreversible impact on that river. Even with the return to 21 per cent, it’s not going to be the Snowy River of old. Our job is to make it return to the maximum extent possible.”

Paddling and politics

The Snowy was silt-brown and hard to see through but literally roiling with life. A few hundred metres further upstream, I’d flopped out of the raft into the river’s pleasantly tepid December waters, browner than usual because of soil washed in by thunderstorms, and almost landed on a surfacing platypus. I was on a three-day paddling journey on the Snowy in Victoria, from Campbell Knob to New Guinea spur. I’d long wanted to see Tulloch Ard Gorge in Snowy River NP, which is accessible only from the river, and had jumped at the chance to join a trip organised by local MP Craig Ingram. “I’ve been coming here for 20 years,” Craig tells me that night, while he tries – unsuccessfully – to impart to me the rudiments of fly-fishing. The steeper, rocky banks here, and some reliable tributaries upstream, combine to make this stretch of river less altered than any other except its high-country origins. “For me this part is spectacular, this is the real Snowy River,” he says. “To allow something like this to deteriorate seemed pretty criminal to me.”

When people around Craig urged him to stand for the seat of Gippsland East in 1999 he resisted at first, but eventually went for it, his candidature an all-or-nothing proposition. A decade later the plodding pace of improvement to the river must be like water torture, but Craig’s mostly diplomatic. “The drought and water security generally has been at a very low level for most of the time we’ve returned flows to the Snowy,” he says. “So until, or if, we get back to some natural rainfall seasons and we start putting water back in reservoirs, we’re always going to have some low flows.”

Craig has the goods as a politician: he’s a big, sporty, broad-smiling bloke, a country boy with a nimble intellect disguised by vowels that lengthen and settle like a good fly cast. But you’re hard-pressed doubting what touches his soul as the heat drains from the day and the flies stop pestering and the evening sky slowly eases off the dimmer switch for its stars. “I’d love to see people know more about the river, and for it to fulfil some more economic potential for the area,” Craig says. “But if I had to reduce it to the basics, I’d just like to see the river healthy enough to sustain itself – so my kids can catch a bass here one day. If you get vegetation and the flow right you can restore the river. But it takes time. And that’s the message: these things don’t happen overnight.”

Postscript

In January and February the Snowy River received environmental “flushing” flows of 900 ML/day for two days, designed to improve water quality between Jindabyne and Dalgety. “These mimicked the inflow from a thunderstorm higher in the catchment,” says catchment manager Brett Miners. “This is the first time we’ve had anything more than base flows, and it’s expected they’ll improve the river’s pools and riffles- which are its ‘engine rooms’ of production. They have also rekindled a sense of excitement in the recovery of the river. Kayakers from the region were all trying to work out which sections will be the most fun with these type of flows – something that’s been missing for 45 years.”

Late in April, Victorian independent MP Craig Ingram challenged the Federal Government to spend $3.34 million buying water on the open market to remove the Snowy’s 56,000 ML ‘debt’ to Snowy Hydro. (See the related news story on the recent flows released in November). “It’s loose change in the scheme of things,” Craig said. The debt accrued during the first four years of environmental releases under the Heads of Government agreement, which stipulates that the Snowy River’s flow will be capped at 38,000 ML annually – 4 per cent of natural flow – until the debt is repaid.

Source: Australian Geographic, Issue 99 (July – September, 2010)

RELATED STORIES