The damage to Australia’s biodiversity

IT’S JUST AFTER 6 a.m. in the north of the Simpson Desert, 135 km south-west of Boulia, Queensland. The moon is still high, but dawn’s pink glow has faded and the last stars are winking out as the sun crests a 10 m high dune.

Rain – the most to quench this parched region for 30 years – has fallen sporadically during recent months and the red sands of the Simpson have erupted with life.

The spinifex has set seed and its yellow stems carpet the swales between the dunes like endless fields of wheat swaying in the breeze. Dotted throughout are gnarled gidgee trees – tough old buggers that predate European colonisation and have survived endless boom-bust cycles and decades of grazing.

Ecologist Max Tischler strides ahead of me, his loose shirt and baggy jeans smothered in red dust and unruly, sun-bleached dreadlocks kept in check by a baseball cap. Clouds of locusts rise as we walk.

His quarry today is small desert mammals, which we hope to find in 60 cm deep pitfall traps set the night before.

I’ve joined Max and freshwater ecologist Adam Kerezsy, both from conservation group Bush Heritage Australia (BHA), on a biodiversity survey of the Ethabuka (2155 sq. km) and Cravens Peak (2330 sq. km) reserves. Once cattle stations, now wildlife havens, they were bought by BHA in 2004 and 2005.

We work along the dunes and find two lesser hairy-footed dunnarts and a pregnant sandy inland mouse.

One dunnart clamps its tiny teeth onto Max’s thumb; at a casual glance it looks like a rodent, but a weird jaw shape gives it away as a carnivorous marsupial. “They’ve got a bit of spunk as you can see. They really have a chew when they want to,” Max says.

This dunnart species was only described in the early 1980s. It’s not unusual for new plants and invertebrates to be discovered on these reserves, and there’s even more chance this year with life booming.

But, explains Max, the sad reality is that species are being lost in Australia’s arid interior before they can even be fully catalogued. We work in tandem to check the lines of traps and find many are empty of the marsupials we hoped to find, including the dunnart’s larger relative, the mulgara.

“The conservation issues are urgent in the arid zone,” Max says as he kneels by a trap on the dune crest. “In the 20 years that the University of Sydney has been studying this region…a couple of species have dropped out of the tracking records.

Whether that’s a local extinction, or they’ve dropped into very small numbers which are not turning up on the tracking grids, we’re not sure.” The empty traps are symptomatic of a wider problem: species that should be here are missing and footprints left nearby by a larger animal hint at one of the reasons why.

Australia’s desert ecosystem and biodiversity

Though ecosystems and species have suffered across Australia, desert mammals are hardest hit.

One-third of the species here in the arid zones when Europeans arrived in 1788 are now missing forever, and the ranges of many formerly common species have retracted by more than 80 per cent.

“Virtually all medium-sized marsupials – hare-wallabies, rat-kangaroos, bandicoots, bilbies – have now been lost,” says Professor Chris Dickman, a desert ecologist at the University of Sydney. “Burrowing bettongs were once found across three-quarters of the continent, but there are just a few thousand left.”

Similarly, rufous hare-wallabies – once found across nearly 2 million sq. km – survive on just two small islands off WA, their total population having declined by 99 per cent.

In the 1970s and 1980s, conservation biologist Andrew Burbidge, now retired from the WA Department of Environment and Conservation, led expeditions into the Great Sandy, Tanami, Gibson and Great Victoria deserts to gather Aboriginal knowledge about dwindling species.

The results showed that many marsupials had been more widespread and common than scientists previously knew.

The burrowing bettong, for example, was recognised by nearly all elderly Aboriginal people approached by Andrew’s team. They recollected that it had “excellent meat” and an “ability to kick viciously when caught”.

A scientific paper in 1988 documenting the results of the expeditions reported that, although the species was already lost from the mainland, old warrens were common and easy to find in many of the deserts.

Aboriginal knowledge also revealed that pig-footed bandicoots and lesser bilbies had been much more common and survived on the mainland 50 years longer than thought.

Across the continent, 28 species and subspecies of mammals (17 of them marsupials), have become extinct since Europeans began settling the continent. Another eight are now found only on islands.

Although just one bird, the paradise parrot, has so far disappeared forever from the mainland, 23 species have become extinct on islands – with Lord Howe and Norfolk particularly affected. Many other species, such as the night parrot and regent honeyeater, teeter on the edge.

Nationally, 49 plants have been lost, but more than 150 are listed as extinct or presumed extinct at State level. Many reptiles, fish and amphibians are now threatened, though these groups have suffered far fewer extinctions.

The latter group is particularly vulnerable in the wake of a fungal disease now ripping through frog populations (AG 81). The situation for invertebrates is difficult to gauge.

These insects, spiders, worms and other creatures without backbones are thought to make up 95 per cent of Australian animal species. Most haven’t yet been formally described or are not well known to science and this, says Andrew, means it’s not possible to even assess whether they are threatened.

But the pattern of loss of vertebrates and plants suggests that many invertebrate species are also likely to have disappeared from significant tracts of their former ranges.

“Today, Australians are justifiably proud of their achievements in many fields of endeavour,” Chris writes in his 2007 book A Fragile Balance. “But one record is less well known and is certainly not one to brag about.”

He refers to the fact that Australian species account for nearly one-third of the world’s recorded extinctions since 1600 – a statistic that suggests we’ve been very poor stewards of our biodiversity.

Australia’s waves of extinction

Strung along the swales and over the dunes for hundreds of kilometres of the Simpson Desert are the vestiges of a fence – tattered and termite-ridden in places, buried or broken elsewhere.

Max tells me about it on my second day out on the biodiversity survey and when we get close, he pulls up the four-wheel-drive and we hop out for a look.

Colours are intense in the Simpson; the rich red of the sand contrasts with the deep blue of the sky and the bright green of post-flood foliage. Delicate pink and yellow wildflowers clamber over the weather-beaten gidgee stumps and sagging chook wire remains of the fence.

Construction of Queensland’s rabbit-proof fence began in 1886, and it was maintained until 1905, but failed to contain the northward march of the pastoral pests. Men were employed to maintain stretches – 30 to 40 miles (48–64 km) each – and several lived in huts on Ethabuka and Cravens Peak.

Bush Heritage actively manages its reserves by removing livestock, sealing bore holes, conducting controlled burns and managing invasive species, such as rabbits.

“It’s quite a complex tapestry to tease apart, but we try to aid the recoveries of populations by focusing on controlling feral animals and fires,” Max says. “We attempt to control fox numbers…and we do all we can to keep the camel numbers low.”

Chris has run a long-term research project out in this part of the Simpson for 20 years. He tells me that Australia’s first wave of marsupial extinctions, in about 1850, took out mostly small native rodents. These were optimal prey for feral cats, which probably arrived with the First Fleet.

A second extinction wave followed between about 1880 and 1900 and began taking out medium-sized mammals (300 g to 3 kg), such as the eastern hare-wallaby and crescent nail-tail wallaby. Again, feral animals – foxes, in 1855, and rabbits, introduced in 1859 – were mostly responsible.

However, as cattle herds and sheep flocks grew, competing marsupial grazers came to be viewed as mortal enemies by pastoralists, as did dingoes.

“The concept of terra nullius [land belonging to no-one], long applied to deny Aboriginal people their right to land, could at this stage be extended to other, less familiar life forms,” Chris says. “Battle was thus [engaged] with all things native.”

What ensued was a holocaust of native animals, terrible and awesome in scale. In 1879 the Marsupials Destruction Bill was tabled, although not passed, in NSW.

The following year the NSW Pastures and Stock Protection Act was passed: dingoes and all kangaroos, wallabies and pademelons were identified as pests and bounties offered for their pelts.

In 1877 Queensland passed the Marsupial Destruction Act, which is estimated to have led to the deaths of 27 million medium-sized marsupials before it lapsed in 1930.

Under the act, landholders could be prosecuted for not exterminating marsupials. Countless tonnes of strychnine were dumped in the bush, says Chris, and manufacturers that produced horse-drawn carts for the exclusive distribution of the poison were established in Sydney.

With dingoes out of the picture, and large-scale land clearing underway, foxes and cats polished off many remaining small marsupial species. “It was a massive onslaught,” says Chris “It’s staggering that these aspects of Australian history are not widely known.”

There’s now good evidence a third wave of extinction took place in the mid-20th century when some surviving mid-sized marsupial species, such as the pig-footed bandicoot and the burrowing bettong, disappeared.

This loss was linked to the decline of traditional indigenous land-burning practices as Aboriginal people left the land and moved into settlements – leading to an increase in the frequency and intensity of uncontrolled bushfires.

The 1988 study led by Andrew Burbidge observed that Australia’s indigenous people were “greatly saddened by the disappearance of the culturally important species”.

Often, Aboriginal people blamed themselves for the disappearance of a species because they ceased to perform the relevant ceremonies after they had left their traditional lands.

You might think these waves of extinction are legacies confined to the past, but in fact they continue today.

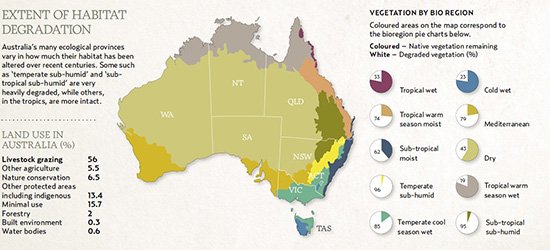

Australia’s habitat degradation

Across northern Australia’s tropical forests and savannahs, spectral stands of dead northern cypress pines are testament to a declining species.

These distinctive-looking lifeless pines reached adulthood before succumbing to death by natural causes, but they remain standing for decades and are particularly noticeable now because there are few younger trees to replace them.

While adults are relatively fire-resistant, saplings of this species need a decade free from high-intensity flames to mature, which they rarely get today, explains Charles Darwin University ecologist Dr John Woinarski. These ghosts in the landscape symbolise a wider loss of plants and animals in the region.

The great decline of species in Australia’s remote and arid interior contrasts with losses elsewhere on the planet that are typically linked to intense development.

“[Such] losses have generally been perceived as historical events – a past and regrettable ‘shock-of-the-new’ response to the incursion of novel threats that accompanied European colonisation,” states an as-yet-unpublished study co-authored by John.

But modern monitoring programs are turning up startling, little-publicised results that suggest that – despite widespread environmental awareness – biodiversity declines continue on a huge scale in modern Australia.

It’s also surprising that they are occurring in our most protected habitats, such as Kakadu National Park. “There has been an extraordinary decline in native mammals across much of northern Australia over the last 20 or so years,” explains John. “This decline has been recorded in many areas and for many species.”

We have few accounts of northern wildlife from the time of colonisation, but Norwegian zoologist Knut Dahl kept records as he travelled across the Top End and the Kimberley between 1894 and 1896.

Of the burrowing bettong, now extinct on the mainland, he noted: “The ground was nearly everywhere and in all directions excavated by the burrows of this little Macropod…all the scrubs and especially the slopes…are inhabited by countless numbers.”

Similarly for the brush-tailed phascogale, a small carnivore that has been recorded fewer than 10 times during the past 20 years in the NT, Dahl recorded that “nearly everywhere inland it was very constant and on a moonlight walk one would generally expect to see this little marsupial”.

The best current data are gathered from more than 100 monitoring stations in Kakadu NP, theoretically a flagship protected environment. “The number of ‘empty’ plots – where no native mammals were recorded – increased from 13 per cent of plots in 1996 to 55 per cent of plots in 2009,” John says.

The culprit is likely to be increased fire frequency, which acts in tandem with cats to create a “double whammy” says Iain Gordon, a CSIRO ecologist based in Townsville. “[Current] fire and grazing regimes have created a lot of open habitat, which has made it easier to hunt small mammals.”

An additional factor driving the loss of predator species, such as the northern quoll, is the relentless spread of cane toads (AG 44).

Declines continue for other groups, too. The Government’s latest Assessment of Australia’s Terrestrial Biodiversity report concluded that most of our “biological assets are still in decline, and threats are ongoing and compounded by climate change”.

In the two decades prior to 2007, conservation group Birds Australia documented a decline of between 11 and 51 per cent in the number of woodland bird sightings it collected. It reflects losses in range and abundance for species such as the flame robin and dusky woodswallow.

Meanwhile, Australian frogs have suffered significant declines with many species affected by the chytrid fungal disease – particularly those high-altitude inhabitants of the eastern ranges.

Statistics for our freshwater fishes are also alarming: catch data for the Murray-Darling Basin collected during the past 100 years show native fresh-water fish are now at less than 10 per cent of historic levels.

Even in the face of continuing declines and public support for conservation, land clearing at a national rate of 6000 sq. km a year continued until 2000, largely in Queensland and, to a lesser extent, NSW.

This has had major implications for Australian biodiversity and Chris estimates that the 4460 sq. km of land cleared in Queensland between 1997 and 1999 alone resulted in the deaths of about 1.9 million marsupials.

Sources: The EPBC ACT list of threatened fauna and the Australian Natural Resource Atlas (2000).

Climate change: the new threat to Australia’s biodiversity

Now a new threat looms. Already the driest inhabited continent, Australia and its biodiversity will suffer further as temperatures rise with climate change.

Many species, already surviving in fragmented habitats, will find that they have nowhere to go as their comfort zones shift north or to higher altitudes.

Rare cold-loving Australian animals, such as the mountain pygmy possum and Leadbeater’s possum, “will have little habitat left in the hothouse to come and so walk the world as zombies”, laments Chris.

Not just species, but entire habitats are at risk. The World Heritage-listed freshwater floodplains of Kakadu NP face inundation by salt water during the next 30 years with sea levels off the NT rising at twice the global average (for reasons that are unclear).

Corals of the Great Barrier Reef are already dying at alarming rates due to the effects of bleaching related to rising sea temperatures. And increasing acidity in ocean water, caused by dissolved carbon dioxide, is slowing coral growth rates.

The problems seem insurmountable, but many argue they are not. Big problems require bold solutions and some scientists have new and controversial ideas about how to stop our biodiversity crashing.

“We are still losing so much it suggests that we are doing something wrong,” says Iain, one of many respected scientists now calling for a whole new approach.

But if we are prepared to face the full scale of the problem, there may be light at the end of the tunnel.

AUSTRALIAN GEOGRAPHIC thanks Bush Heritage Australia, Mark and Nella Lithgow, Max Tischler and Adam Kerezsy, who helped get the team to the Ethabuka and Cravens Peak reserves.

Source: Australian Geographic, October/December 2010

RELATED STORIES