This is why you should love spiders

AUSTRALIA HAS AN incredible diversity of native spiders, including the potentially lethal funnel-web, the ubiquitous huntsman, and the charming peacock spider. Only two can be deadly for humans – the funnel-web and redback spiders – and we have antivenom for both.

Found all across the country, spiders play an important role in the environment as generalist predators. Increasingly, their venom is being used to develop novel human therapeutics and to create new, selective, sustainable insecticides.

A model citizen

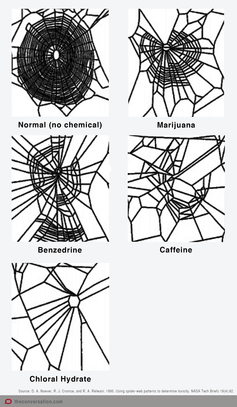

How house spider webs change when the spider is exposed to different chemicals.

Spiders are often a starting point for children to fall in love with the natural world: they’re found almost everywhere, and everyone can appreciate their tremendous diversity. What’s more, scientists are constantly learning new things from them.

They’re an important model system to help us understand the basics of biology. We know that the spider and its web are so closely tied that exposure to different chemicals has specific effects on how the webs are spun.

Other research suggests the blue colour in tarantulas evolved independently at least eight times. This may help inform our understanding of the evolution of colouration, as well as how to make better paints.

The peacock spider has helped show that strong sexual selection by females depends on a variety of factors. Scientists think sexual selection has had an impact on the striking colouration and complex signalling of this spider species, but this is the first evidence to definitively demonstrate female preference has played a role.

Dance, dance revolution

With great power…

As a generalist predator, spiders help limit the number of insects in your garden. Although they’ll probably eat some good bugs as well as bad while they’re at it.

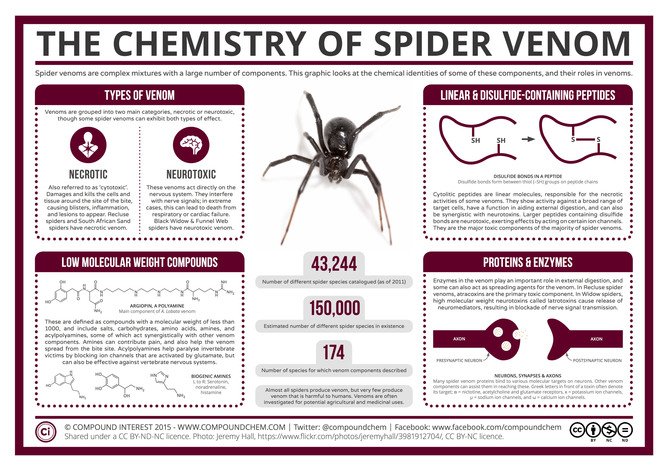

Spider venom is a complex chemical cocktail of hundreds of different components, and each type has its own very specific activity. Many individual venom components act on the insect nervous system and these can be very useful for scientific research.

My work, for instance, is on discovering newenvironmentally friendly insecticides from spider venoms. Since insect nervous systems are very different from the one found in vertebrates (including humans), individual toxins are frequently active in insects but not in vertebrates, and vice versa.

The Chemistry of Spider Venom. (Image: Compound Interest, CC BY-NC-ND)

When we look for good insecticidal candidates we screen for compounds with specific activity in insects and the absence of activity in vertebrates. It’s that specificity that makes spider venoms such powerful sources of new, sustainable insecticides, as well as excellent therapeutics.

What’s in a venom?

Spider venoms generally consist of three types of components: small components (salts, carbohydrates, amines and acids to name a few); peptides (small proteins that are generally highly structured); and enzymes (used for digesting food).

If you get bitten by a spider, do your best to remain calm, and proceed directly to a medical professional so your symptoms can be monitored and treated. They will administer the appropriate antivenom if required.

The Conversation

Spiders deliver venom by injection, using mouth parts called chelicerae, which are informally known as fangs. The chelicerae are found on the front body segment, the cephalothorax, and that’s also where its eight legs are attached.

The abdomen is the other spider body segment, and that’s where the spinnerets, used to weave the web, are found.

Spiders sometimes appear hairy, but those are actually sensory setae that are used to collect detailed information about the nearby environment. Depending on the spider species that could include temperature, humidity, and wind direction, and chemical information, such as the source of pheromones used in mating.

So leave your fear behind and go ahead, embrace the majesty of spiders. But pick your species carefully – and try not to get the police involved.

![]()

Maggie Hardy is a Postdoctoral Research Fellow at The University of Queensland

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.