More than 1000km of the Great Barrier Reef has bleached

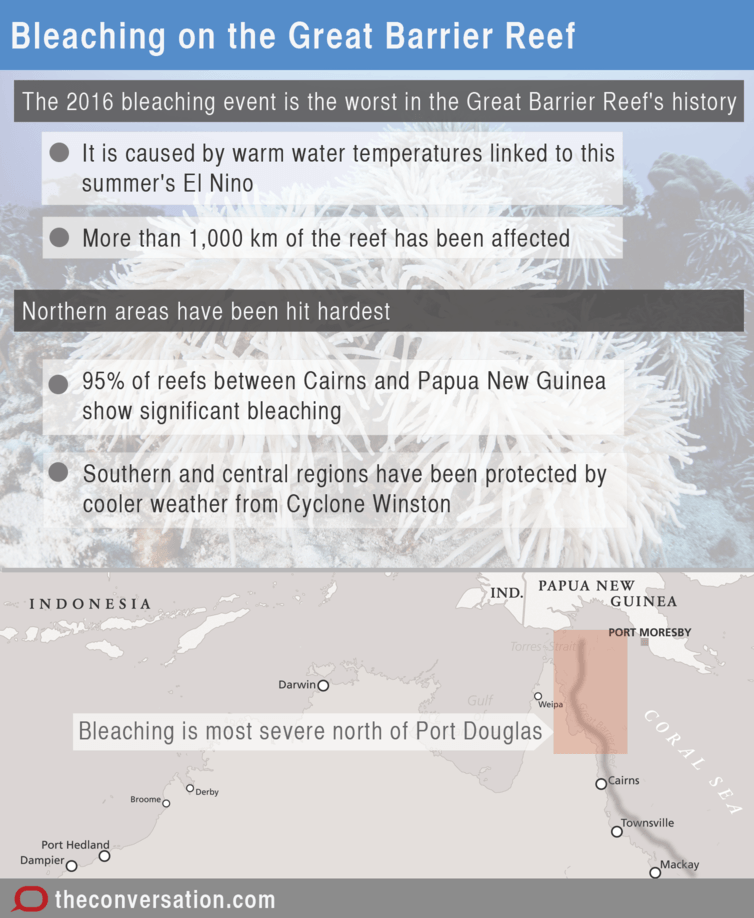

ONE OF AUSTRALIA’S most important natural assets, the Great Barrier Reef (GBR), is being affected by the worst ever bleaching in its history, amid warmer than average water temperatures associated with this summer’s major El Niño event and against a background trend of ongoing ocean warming.

With extensive coral bleaching having been predicted as far back as October last year, Terry Hughes at the ARC Centre of Excellence for Coral Reef Studies convened the National Coral Bleaching Taskforce to document the bleaching, both from the air and at close quarters.

With our survey work still ongoing, a bleak picture is emerging: more than 1000km of the Great Barrier Reef shows signs of significant bleaching. In the worst-affected areas, in the GBR’s previously pristine far north, many corals are now expected to die.

Bleaching, such as on this anemone, is worst in the Great Barrier Reef’s remote north. (Source: CoralWatch.org)

Warning signs

At the start of southern summer it was predicted that bleaching would be largely restricted to central and southern parts of the GBR. As it turns out, the first indications of a problem came from scientists working at Lizard Island, in the reef’s remote north. In January, Jodie Rummer of the ARC Centre of Excellence for Coral Reef Studies was studying fish near the island when she noticed that many of the hard corals, soft corals and even clams were starting to bleach.

Shortly thereafter, staff from the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority, undertaking routine surveys in the northern GBR, reported that not only were many of the corals bleached on reefs near Cooktown, but some of the corals had already started dying.

The full extent and severity of the bleaching in the northern GBR became apparent when our colleague Terry Hughes led a team on a series of aerial surveys, similar to those carried out during the 1998 and 2002 GBR bleaching events.

It was expected that these surveys would show that bleaching was restricted to the reefs at and around Lizard Island. But detailed aerial assessments of bleaching severity at 500 reefs have instead shown that 95% of reefs stretching between Cairns and Papua New Guinea have experienced significant coral bleaching. Only four reefs showed no evidence of bleaching.

How do the surveys work?

During aerial surveys, each reef is given a score from 0, indicating no bleaching, to 4, indicating that more than 60% of the corals are bleached. Comparing the results of the latest aerial surveys to those from previous bleaching episodes, it is clear that this bleaching event is far worse.

In 1998 and 2002, fewer than 200 reefs were assigned to the highest bleaching categories (3 or 4), compared with 450 already this year. Moreover, aerial surveys are now continuing on reefs south of Cairns, where bleaching is also being reported.

Extensive aerial surveys are being complemented by in-water surveys by coral biologists. By getting in the water, scientists are better able to ascertain the severity of the bleaching, establish which types of corals have been worst affected, and make predictions about what proportion of the bleached corals are likely to die. The trade-off is that they cannot cover as many locations as an aerial survey.

In places where both aerial and in-water surveys have been conducted, the results match very closely. Near Port Douglas, for example, where aerial surveys revealed many reefs had a score of 4 (greater than 60% bleaching), divers have confirmed that at least 75% of the corals on the shallow reef top are bleached. Similarly, reefs in this region that scored only 2 or 3 from the air show corresponding levels of bleaching in in-water surveys.

The overall pattern

While bleaching surveys are ongoing, a distinct pattern is emerging, whereby the severity of bleaching declines from north to south. Virtually all of the reefs in the GBR’s remote far northern section have been hit very hard. Here, virtually all of the corals, including normally very robust types, are bleached.

Given the severity of the bleaching, we expect that many of the corals in this region will die. This is concerning, given that the GBR’s north was considered “most pristine” in the latest Great Barrier Reef Outlook Report.

Bleached coral near Port Douglas. (Source: Cassandra Thompson/ARC Centre of Excellence for Coral Reef Studies)

Between Cooktown and Cairns – an area of the reef that is particularly important for tourism – the bleaching is much more variable. There are certainly some reefs where up to 90% of the corals are bleached and death rates are expected to be very high. But the extent of bleaching at other nearby reefs is much more moderate, enabling tourists to visit reefs that are still in good condition.

Further south, the extent of bleaching is even more variable and generally less severe. Ironically, the weather disturbance that persisted from Tropical Cyclone Winston, which devastated Fiji in February, helped to cool surface waters over the central and southern GBR, reducing the heat stress suffered by these corals.

Work is continuing to establish the southernmost extent of significant bleaching, but it is clear that a very large stretch (more than 1,000 km) of the GBR has been affected.

While the full extent of the bleaching, as well as the social, ecological and economic impacts, are yet to become apparent, this is undoubtedly the worst known bleaching event on the GBR. The National Coral Bleaching Taskforce will continue to coordinate research throughout 2016 to get a more complete picture of the severity and consequences of this event. The Taskforce is also currently monitoring thermal conditions on Western Australian reefs, which are now at their most critical time for bleaching to occur.

![]()

Morgan Pratchett is a Professor at the ARC Centre of Excellence for Coral Reef Studies, James Cook University and Janice Lough is Senior Principal Research Scientist at the Australian Institute of Marine Science.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.