We’re near the southern end of Queensland’s Wet Tropics World Heritage Area, where rainforest is treated like a botanical deity and people willingly stand before bulldozers to protect it. And yet here we are, with rangers from the Queensland Parks and Wildlife Service (QPWS), Terrain NRM and Girringun Aboriginal Corporation, setting fires to hold the stuff back.

Rainforest annually brings this region many millions of tourist dollars, but it is clearly not welcome everywhere. The rangers here are among land managers using late-winter, low- intensity fires to keep rainforest plants out of coastal forest types considered just as biologically precious. It’s a controversial practice that underpins a difficult ecological balancing act.

The habitat we’re working to protect is on the Bruce Highway’s inland side, near Cardwell. It’s a mixed forest where several species of melaleuca – also known as tea-tree or paperbark – are dominant. And the plan is to keep it that way by burning the understorey and rainforest species creeping in from the west. If they gained access, they’d force out the melaleucas and associated species.

It’s an incredibly important area worth preserving, explains, QPWS conservation officer Mark Parsons. “Up the top,” he says waving at a rise behind us, “is Bishop’s Peak where we have the blue banksia, which occurs only on Hinchinbrook Island and here on the adjacent mainland.”

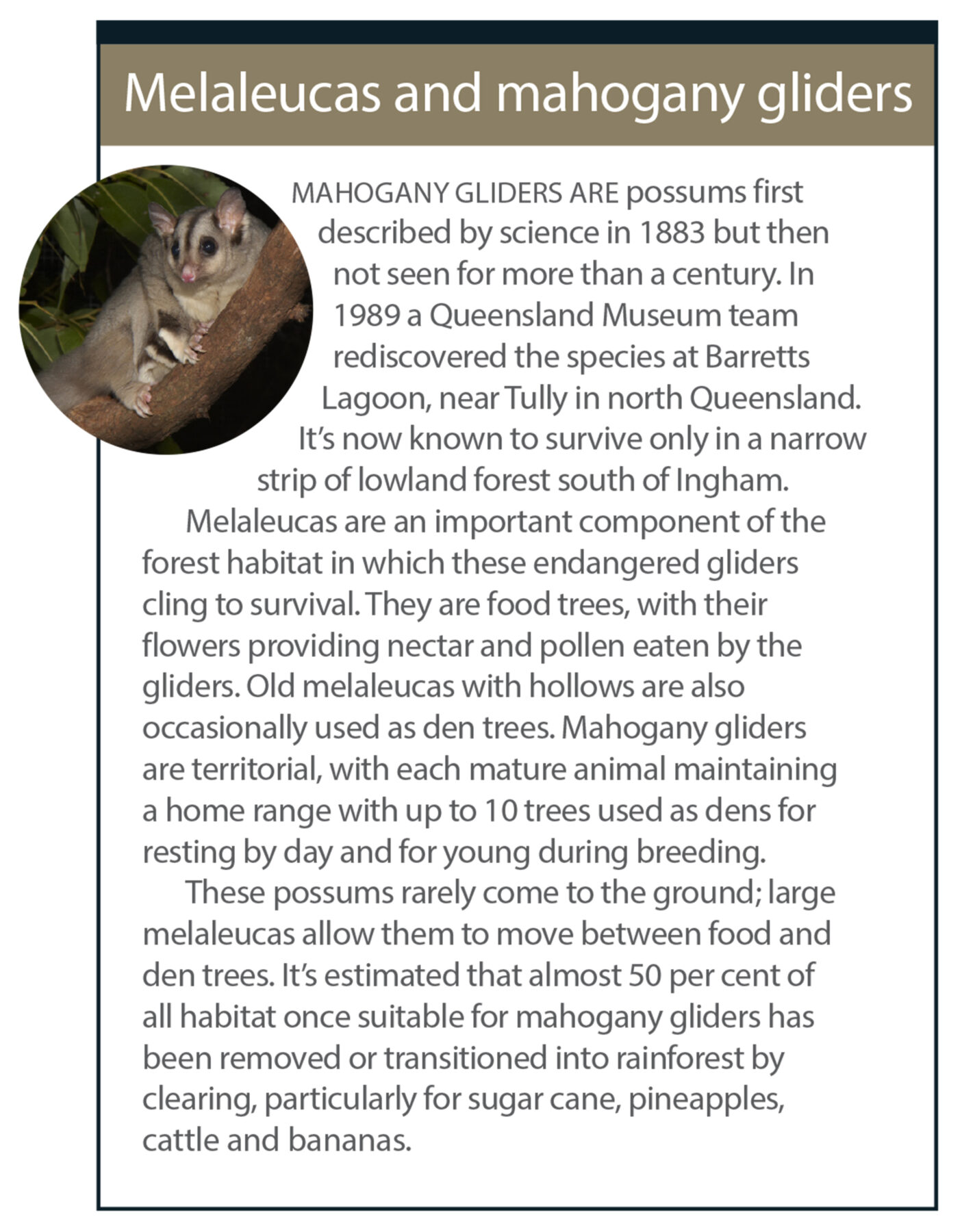

The mixed paperbark forest, Mark adds, is also prime habitat for endangered mahogany gliders, found only in this coastal southern region of Queensland’s wet tropics. These possums rely on tall melaleucas and other canopy trees here to leap between feeding and den sites. Encroaching rainforest species force the gliders out of the already limited area where they survive.

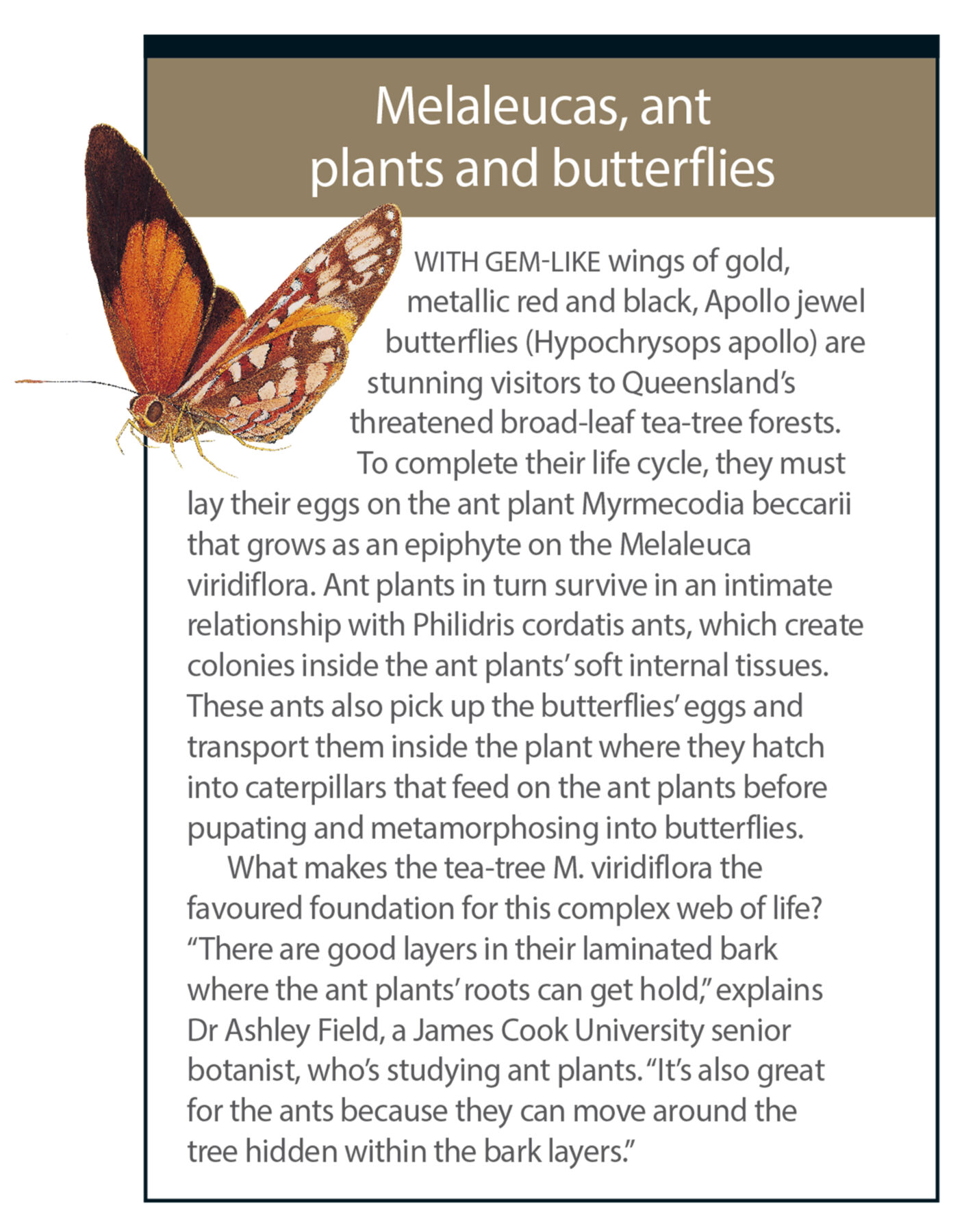

One of the most compelling reasons for this burn, however, is to set up a firebreak to protect what lies a few hundred metres across the road from an out-of-control wildfire. Here, on the highway’s eastern side, is Sunday Creek, a thin mangrove-lined link with the Pacific Ocean. And wedged between the mangroves and a road lined with mixed melaleuca forest is a special stand of trees clinging to survival. The dominant species of this endangered plant community is the broad-leaf tea-tree, Melaleuca viridiflora. And around and below the tea-trees is a complex association of species, from paper daisies and ground orchids to ant plants and the Apollo jewel butterfly. It’s a forest type that was once widespread in north-eastern Queensland, but agricultural clearing, weed encroachment and damage by grazing stock and feral horses and pigs mean it now survives in only fragmented pockets. It’s been federally listed as endangered and protected since 2012.

Also working against the survival of broad-leaf tea-tree forests and, in fact, most large paperbark stands throughout Australia, is the preference of these trees for damp, swampy habitats. Up here, as it’s been throughout much of the country’s settled areas, these low- lying, wet/dry, fringe habitats have traditionally been filled in, destroyed and ‘reclaimed’ for dryland uses. There are still signs everywhere in north-eastern Queensland of just how extensive the coverage here by melaleucas would have once been.

“Much of north Queensland’s cane and cattle farms would have been covered by paperbarks,” Mark explains, “and you can still see the huge old trees, remnants of wider forests, across properties in the region.”

ONCE YOU BEGIN looking for the distinctively shaggy, paper-like bark of melaleucas, you see them everywhere. Around Cairns the humid summertime air fills with the burnt caramel perfume of the flowers of the weeping paperbark, M. leucadendra, and swamp tea-tree, M. dealbata. Lorikeets descend on them in huge screeching flocks to feed on their rich nectar. So too do spectacled flying foxes; sometimes in such numbers that flights into and out of Cairns airport are delayed.

Melaleucas aren’t only tropical trees, although most surviving paperbark forests are in Queensland, particularly Cape York Peninsula, and the NT’s north. These moisture-lovers occur right around Australia and you’ll see them fringing suburban streets, in small urban parkland stands, and lined up as windbreaks on coastal farms.

Away from settled areas, they line riverbanks and estuaries and fill swamps. Physically, they’re as distinctive, ubiquitous and uniquely Australian as eucalypts. In fact, melaleucas are related to the eucalypts as part of the largely southern hemisphere family of plants called Myrtaceae.

Some 63,000sq.km – about 5 per cent of Australia’s forested area – are still covered by melaleucas, making it our third-most dominant forest type after eucalypts, which cover about 74 per cent, and wattles. Scientifically, Melaleuca is the genus name, as well as one of the group’s common names. And it now contains almost 300 recognised species, all but a handful of which are endemic to Australia.

Most grow to less than 10m and some – mainly in south-western Australia – are described as ground-huggers because of their low-growing form. About 15 species, however, grow taller, including at least seven that reach more than 20m.

The group is at its most diverse in WA, where there are about 240 known species, many in the south-west. But there’s no question melaleucas reach their most magnificent best in the tropics where they can form dense forests of very large trees.

ONE OF THE country’s most spectacular and accessible melaleuca forests dominates the wetlands of Eubenangee Swamp National Park, about 70km south of Cairns. The park sits in the lowlands east of Australia’s wettest place, the Bellenden Ker Range, which includes Queensland’s two highest peaks – Bartle Frere and Bellenden Ker. Eubenangee remains a mostly damp and soggy place, even during the dry season, but it’s flooded right throughout the Wet when the melaleucas here spend months with their roots and lower trunks submerged.

The swamp water is unappealingly tea-coloured due to the tannins that leach out of the melaleucas – toxic chemicals that deter insects from the trees – but it’s clean. Not that you’d want to swim here, because it’s full of crocodiles and mosquitoes.

The site also ripples with birdlife, and with at least 190 documented avian species – ranging from spoonbills and ibis to reed warblers and herons – it’s popular with birdwatchers.

Eubenangee’s melaleuca forest is an alliance of four of the largest species – M. quinquenervia, M. cajuputi, M. leucadendra and M. dealbata. But 90 per cent are quinquenervia. The swamp is surrounded by cane and cattle farms and has suffered much from agricultural drainage. A lot of water has, however, been redirected back into the area in recent years to ensure the survival of this stunning forest and the significant wetland ecosystems.

One of the biggest threats to the park’s swampy habitat, however, has been invasive weeds, particularly pond apple. It was introduced in 1912 from the Americas as grafting stock for the commercially harvested and related custard apple. It loves warm and wet environments and can spread at such a rapid rate in the right conditions that it’s one of Australia’s worst invasive weeds. In Eubenangee it can grow so densely that it excludes the swamp’s defining melaleucas.

In a perverse irony, the species most responsible for Eubenangee’s stunning swamp forest, M. quinquenervia, has become a serious invasive pest in the USA where it’s often known as the punk tree. The most notable infestations are in the internationally famed wetlands of the Florida Everglades.

In fact, quinquenervia is considered to be among the worst of about 60 invasive weeds threatening the future of this famed habitat, where it forms huge unwanted stands. Many millions of dollars are now spent annually trying to eradicate this paperbark from the World Heritage-listed wetland site.

The result (right) of a high-heat, out-of-control burn started by a lightning strike in an endangered melaleuca forest south of Cairns. Because the roots of many of the paperbarks were burnt, they won’t survive. The grass trees growing in this forest have been luckier and will survive.

IT’S NOT SURPRISING that with paperbarks being so widespread around the continent that they have been used by Aboriginal people for thousands of years for a range of purposes. In the mixed forest opposite Sunday Creek there are several significant Aboriginal sites including one with large melaleucas bearing scars where bark was peeled off for roofing material for shelters known as midja.

Evelyn Ivey, one of the Girringun Aboriginal Corporation (GAC) rangers working with us on the burn, says melaleuca leaves are still widely used by the people of her tribal group, the Girramay, in underground ovens known up this way as Kup-murri. These begin as large holes dug in the ground and lined with rocks over which a fire is started.

Once the fire burns down, a layer of paperbark leaves is placed over that: meat and bush vegetables are added and then the whole thing is covered with more leaves and dirt and left to cook slowly for hours. The result, she says, is “delicious”.

Elsewhere, melaleuca bark was also reportedly used for baby slings and in food preparation and there’s widespread evidence melaleucas were an important source of traditional medicines Australia-wide. The leaves and bark of several species were used to treat ailments from coughs and colds to cuts and sores. These were applied directly or crushed and soaked in water to create a drink or liniment. Alternatively, they were burnt and the smoke inhaled.

Girramay elder Claude Beeron, well known around the Cardwell area simply as ‘Uncle Claude’ and now aged in his 70s, says melaleuca trees were also a guaranteed source of water during the dry and on journeys. He points to the distended swellings that many smaller melaleucas appear to develop on their trunks.

“That’s water storage and a lot of people drink it,” he explains. “It might be salty, but you can survive on it: if you happened to be walking for miles and miles and your neck was dry, you’d cut it with a stone axe and bleed it.” He also recalls that melaleuca bark was lit and used like a torch.

MELALEUCA ALSO HAS an extensive history of use among Europeans. Captain Cook reportedly trialled, unsuccessfully, a tea made from melaleuca leaves as a cure for scurvy, a life-threatening vitamin C deficiency that was prevalent among sailors in the 1600s and 1700s.

Much later, during the 1920s, the NSW state chemist Arthur Penfold reported that distilled tea-tree oil was at least 10 times more effective than the antiseptic phenol, which was widely used at the time. These days, oil extracted from several species, but mostly M. alternifolia, is produced from commercial tea-tree plantations, particularly on the NSW north coast, and used worldwide in the topical treatment of minor infections.

“The main active ingredient is terpinen-4-ol,” explains Dr Joe Brophy, a University of New South Wales chemist who has spent many years investigating the composition of melaleuca oils. “Various species produce different oils and it varies quite a lot within the group. You can get melaleucas that produce something that’s very close to eucalyptus oil and there are a few species that produce lemon-scented oils.”

There’s even one that produces a cinnamon-scented oil that’s used commercially to flavour ice-cream, and then there are some that produce virtually no oil. In those that do, the oil is produced in glands in the leaves. In species that produce high levels of oil, these glands are particularly large and numerous and can be clearly seen when the leaves are held up to the light.

There have been plenty of scientific studies that support the use of tea-tree as a topically applied antibacterial and antifungal, and as a repellent for mites and lice. The oil works, explains Joe, by rupturing cell membranes.

In the past decade there’s also been increasing medical interest in the potential anti-cancer properties of terpinen-4-ol. In 2004 Italian researchers reported that the compound inhibited the growth of skin cancer (melanoma) cells in laboratory studies. There have since been further investigations at various places around the world into the potential of tea-tree oil as an anti- cancer agent, including some promising studies in animals.

For now, however, the development of any pharmaceutical cancer treatment from melaleuca is still a long way off. But it seems poetically appropriate that the country with the highest incidence of skin cancer could find an answer to the disease within the leaves of an indigenous Australian plant.