Can you actually name a star?

ABOUT ONCE A week, I receive an email like this (note that any identifying details have been removed):

I was wondering if you could help me. We are coming to Canberra for 2 nights with our friends whose little girl passed away (a few) months ago from (some) syndrome. We purchased a star in her name (…) and need help locating this star. We have the coordinates. Would somebody be able to help us it would mean the world to us and to her mum and dad as well.

And about once a week, I’m the one to gently explain that the star name they bought is not officially recognised; that the star they want to look at in someone else’s honour is not actually named in that person’s honour.

I don’t want to be that person anymore.

Billions and billions of stars

The great thing about our galaxy, the Milky Way, is that it is home to about 300 billion stars. All of those stars mean a nearly endless supply of merchandise for companies to sell.

The Milky Way. (Image Credit: ESO/S. Brunier)

There are several companies offering to sell you a star name, and at many different prices.

One company says it has “named two million stars” since 1979, and its current package for a single star name starts at A$110. It does say that any name purchased is “not scientific but symbolic”.

If you read the fine print of many other companies they usually say that astronomers do not officially recognise the name of the star you just purchased.

But that’s not the only issue I’ve encountered.

Remember, there are many companies selling star names. In the span of one month, two entirely unrelated people contacted us to look at a star that they purchased. It was the same star. These two people had each paid to name the same star.

The official way to name objects in space

The International Astronomical Union (IAU) is the official international body of astronomy, and is the only official authority to name objects in space.

Recently, the IAU approved new names for 86 stars used by other cultures besides the traditional Arabic, Greek, or Latin names, including four stars that now officially bear names based on their Aboriginal Australian names.

Besides naming, the IAU serves a number of other roles such as science and classification of various objects. The IAU is potentially most recently famous for its 2006 determination that Pluto is not a planet, but a dwarf planet.

Every type of object has a different set of rules for naming. For example, asteroids have a set of different rules to comets. For some objects, the discoverer can name it something they’d like. Asteroid 5691 Fredwatson is named after the famous Australian astronomer Fred Watson, and discovered by his friend, the Scottish-born Australian astronomer Robert McNaught.

An object like a comet can be named after the person who discovered it, as is the case of Comet McNaught – this time named after McNaught himself. If that person finds multiple comets, all must have that name so there are more than 50 Comet McNaughts!

Comet McNaught over the Pacific Ocean, taken from the Paranal Observatory in Chile in January 2007. (Image Credit: S. Deiries/ESO)

Sometimes, an object is important enough that the public are given their say. Discoverers can open up the name to a vote, such as 2014 MU 69 in Kuiper Belt, the next target for the New Horizon’s probe.

Official star names

Even stars have a way of officially being named or designated. Some bright stars – ones that have been visible to humans through history – have proper names such as the new ones mentioned above.

Other names that have been around for some time include Betelgeuse in Orion, or Sirius, “the Dog Star” in Canis Major.

But most have alphanumeric names or designations. These numbers, while sounding boring, belong to one of two naming schemes.

Some follow an alphabetic order based on brightness and the constellation they are in. For instance, Betelgeuse is also designated Alpha Orionis, and Sirius is Alpha Canis Majoris.

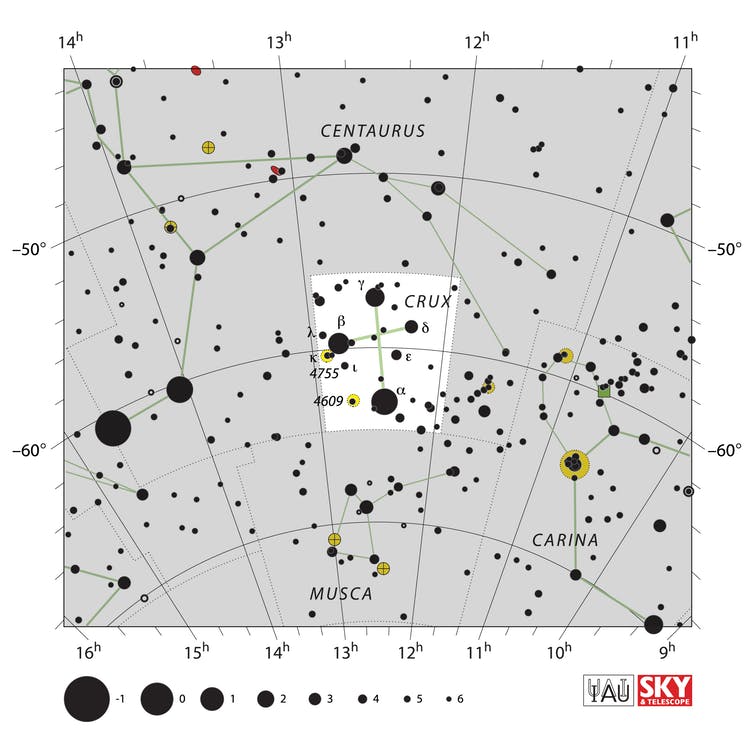

Alpha is always the brightest star in the constellation followed by the constellation name. So there is a Beta Orionis, Delta Orioinis and so on, and also an Alpha Crux, Beta Crux, etc. in the Southern Cross.

The Southern Cross constellation photographed from the Northern Territory over a two minute exposure. (Image Credit: Flickr/Eddie Yip)

The stars of the Southern Cross given their official designation by astronomers. (Image Credit: IAU and Sky & Telescope)

The other method is actually the star’s coordinates in space, their space latitude and longitude, or an officially recognised catalogue number. For instance, the oldest known star, SMSS J031300.36-670839.3, has a name based on the initials of the SkyMapper Southern Survey (SMSS), followed by the right ascension (or space longitude) and declination (or space latitude).

This means it is easy for another astronomer to look up and locate an object, without having to look up a database of the object’s name, and then find its position via a telescope.

You may not agree with this naming convention. Various astronomers may or may not agree with this. But that’s the way it works.

The IAU has this advice for anyone looking to buy a star name:

As an international scientific organization, the IAU dissociates itself entirely from the commercial practice of “selling” fictitious star names, surface feature names, or real estate on other planets or moons in the Solar System.

Remembering your loved ones

I appreciate your desire to remember your loved ones. (I have my own ways that I do it.)

If you are happy to buy a star from one of these companies, and know it won’t be recognised but it means something to you, then please go ahead. I completely respect that.

But you can also choose your own star, perhaps one that you looked at together, to think of a person. Then you can go out and observe the beauty of the night sky for free, and remember them.

Stargazing together. (Image Credit: Flickr/William Prost)

You can even use one of our large telescopes, SkyMapper, and get an image of that star for free.

A few years ago, we saw in the newspaper the wishes of a young child with a life-threatening illness. One of them was to have a star named after them.

Realising the issues with this, we contacted the family and instead named one of the asteroids that the Siding Spring Survey had discovered. Their name was accepted by the IAU as an official asteroid name in recognition of their achievements despite their young age.

![]() I realise that these options may not be open to everyone, but there are many ways to remember someone, to cherish someone, to love someone.

I realise that these options may not be open to everyone, but there are many ways to remember someone, to cherish someone, to love someone.

Brad E Tucker is a Astrophysicist and Outreach Astronomer at the Australian National University.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.