Unearthing Australia’s climate history

FEW PEOPLE realise that snow was once a common occurrence for southern Australia’s climate.

Historical records help document impacts of past weather extremes such as heatwaves, floods, droughts and even snow. Now scientists are using these fascinating resources to uncover more about Australia’s climate history and also shed light on modern severe weather events.

A clearer understanding of Australia’s climatic past lies buried in colonial-era records and documents such as weather journals and ships’ logs, as well as photographs, old newspapers, sketches and paintings. And yet it’s estimated that only half of all the old weather diaries available globally have been analysed.

Even once a record is rediscovered, there’s still the matter of transferring all the handwritten data into digital format, which makes it easier to access for research purposes. Computers have trouble reading cursive numbers and words, especially in tabulated formats like those used for meteorological observations, so this research relies on people. And that’s where citizen scientists can really help – by transcribing centuries-old handwriting in the pages of historical weather diaries.

Reconstructing our climate

Climate scientist Joëlle Gergis, senior lecturer in climate science and director of Climate History Australia at the Australian National University, Canberra, is using historical records to reconstruct the country’s climate variability and extremes.

“Australia is no stranger to extreme weather and climate – from drought to bushfires, heatwaves and floods. We need to look at the past to better understand the future,” Joëlle explains.

“Climate change is making extreme weather events worse than they were in the past because they are now occurring in the background of a climate that is 1°C warmer than it was in the past. The question is, how will a hotter climate impact the extremes we will face in the future?”

Early weather records provide scientists with much detail about Australia’s climate before the Bureau of Meteorology’s official records began in the early 1900s.

“While about 100 years of data is pretty good, given that Australia’s climate is prone to large swings in things like temperature and rainfall, having a longer daily record is really helpful for understanding long-term changes in our weather,” says Dr Linden Ashcroft, a climate history researcher at the University of Melbourne.

“Information from natural data sources like tree rings and ice cores tells us about year-to-year and decade-to-decade changes in our climate. But with daily weather records, we can start to understand the specific conditions that occurred.

“This means we can learn more about individual extreme events like heatwaves and storms – events that cause a lot of damage and that are changing as the planet continues to warm.”

Dr Joëlle Gergis consults old Australian newspapers in the State Library of Victoria, Melbourne, in search of past weather reports and news items. (Image credit: Peter Casamento)

Most information about the world’s climate before the 1900s currently comes from Northern Hemisphere sources. Having historical weather data for Australia would allow scientists to better understand changes specific to the Southern Hemisphere.

Research published in June by the Climate History Australia team presented the longest daily temperature record for Australia back to 1838. It revealed the southern Australian climate once experienced snow regularly and that heatwaves are now occurring more often.

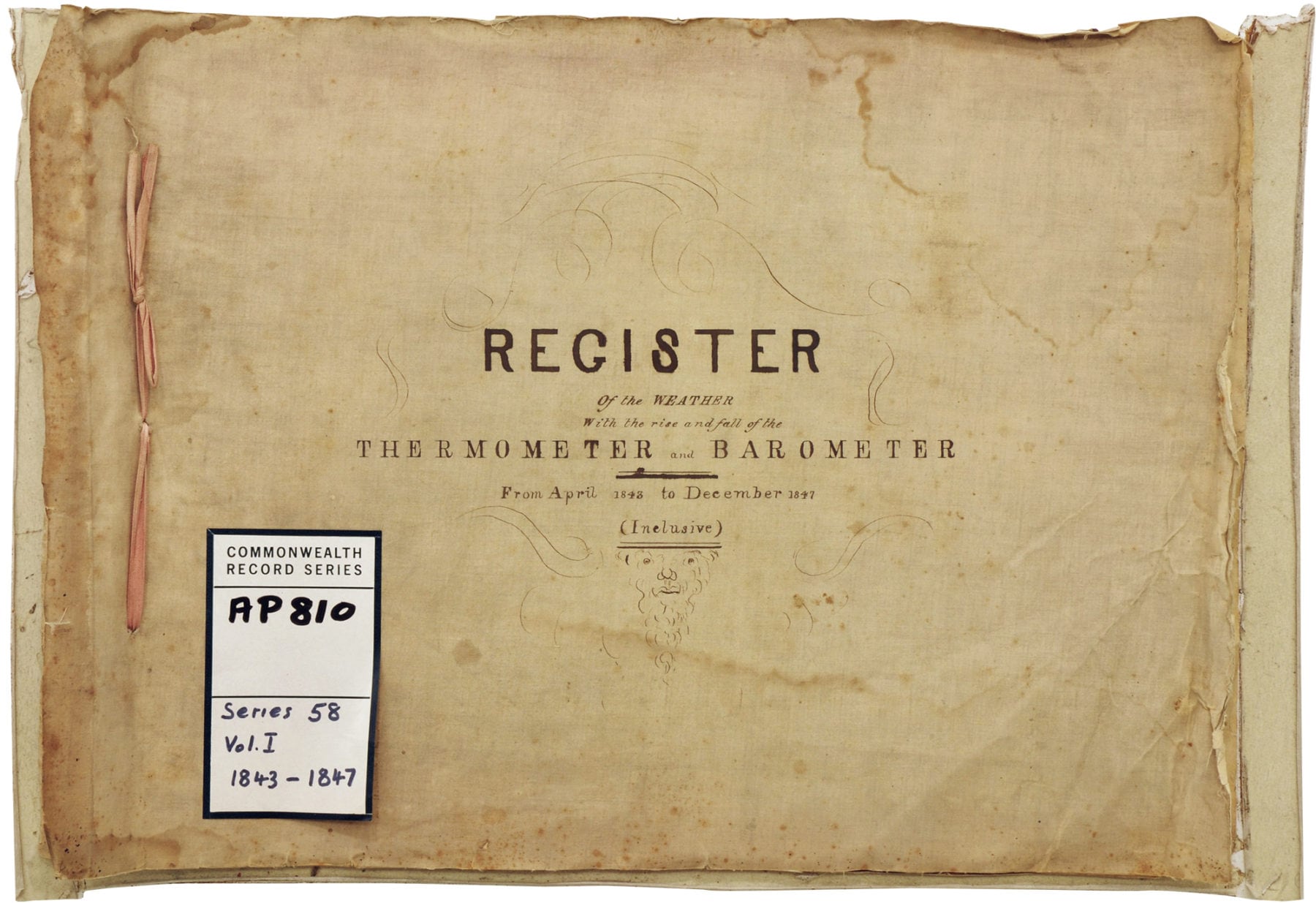

Climate History Australia is currently rolling out citizen science projects across Australia to help piece together more of Australia’s old weather records. Recent efforts have focused on closing an eight-year gap in Adelaide’s daily weather record from 1848 to 1856. Volunteers have digitised more than 4000 days’ worth of data from weather diaries kept at the Adelaide Surveyor General’s Office, which researchers have now begun to analyse.

It was a combination of 15 years of dedicated research and pure luck that led to the discovery of the weather journals in Adelaide. Professor Rob Allan, head of the Atmospheric Circulation Reconstructions over the Earth (ACRE) initiative and an Australian based at the UK Met Office, was the first to locate them through an online search of the National Archives of Australia.

Rob immediately understood the immense value and significance of these records, and asked the citizen science unit of the Australian Meteorological Association to photograph them. Researchers then uploaded pages of the weather journals online, in the hope they’d attract volunteers to help transcribe them.

Digitising weather records

Australia’s climate science projects are a regional effort within the ongoing global program of ACRE. Data rescue projects are underway around the globe, but most are only able to secure funding for a few years at a time. Many have chosen to use the popular citizen science platform Zooniverse.

Earlier this year, Rainfall Rescue in the UK collated 65,000 pages by 16,000 volunteers, producing 5.25 million measurements covering the years 1677–1960. Southern Weather Discovery is working with both volunteers and Microsoft AI for Earth to build a library to help teach computers how to transcribe weather records from New Zealand, the Southern Ocean and Antarctica.

“It’s hard to know for sure, but probably only half of the known historical weather observations have been digitised so far, and the world loses about 500,000 old records each day,” Rob says.

“While most people tend to think of weather observations as being land-based, it’s important to note that a lot of this historical data coming from the colonial period comes from marine-based ship logs. This kind of data can be considered really valuable given that 71 per cent of our planet is oceans.” The ACRE-led international effort has made a small dent in this, but, Rob says, there is much more to do.

“We are working to streamline the flow of the data we have rescued from its recovery to digitisation to analysis and modelling,” he explains. “And we, of course, share the data with anyone who wants it.”

He says citizen science is the area that has the most potential for further growth in historical climatology and he’s optimistic this will be boosted in the near future by breakthroughs in artificial intelligence and machine learning.

Of the two citizen science projects that Climate History Australia is presently working on, one is exploring documents from the Adelaide Surveyor General’s Office from 1843 to 1856. The other is investigating Perth Observatory records from 1880 to 1900.

Wendy Howe has been volunteering on both. “One of the most enjoyable aspects is reading about the very florid, formal and evocative weather descriptions,” she says.

Wendy became so fascinated by the work that she has also helped the researchers collate further information. In the State Library of Western Australia’s catalogue, she found a photo of Government Astronomers Cooke and Curlewis, who made the Perth records she’s helping to transcribe.

“I can easily imagine these proud, professional men diligently recording weather data in their very formal writing style,” she says, pointing to the photo. “See how important they look!”

Joëlle says the location of the Perth records is particularly important because south-western WA is one of the most sensitive regions to climate change.

“It is located in the path of the southern storm track, which is starting to shift south towards Antarctica. This has reduced rainfall in the region, which has led to the need for desalination plants to secure the city’s water supply during periods of drought,” she says.

“What is amazing about the Perth Observatory journals is that our initial inventory suggests it is a complete daily record, which is quite a rare find. It’s phenomenal that in 20 years, only one day is missing.”

A note at the bottom of the journal explains that an observer was sick on that particular day, so no observations were made. The note went on to record that “this is no excuse and other arrangements will be made in future”.

“One of things I appreciate most about working with historical weather data is just how dedicated the observers were to their task,” Linden says.

“Most historical weather observations don’t come from trained scientists. They are from farmers, engineers, astronomers, telegraph operators or ministers – people who were interested in the weather and climate of their new place.

“This kind of dedication to the task inspires me to make the most of their efforts and ensure we can use this past information to prepare us for the future.”

For more information, or to find out how to become involved in these citizen science projects, visit Climate History Australia.