I’m tracking the Dog Fence from above in the front passenger seat of a Cessna 206. We took off in the tiny plane a couple of hours ago from the sandy airstrip that services the Wilpena Pound Resort and Old Wilpena Station Historic Precinct situated in the Ikara-Flinders Ranges National Park in South Australia. From up here, the fence looks like a hairline fracture as it traces a path over dunes, up breakaways and across stony downs before spearing away into the far distance towards rust-hued gibber plains. For graziers, this fine silver line represents the lifeblood of their in- dustry. However, it also poses an immense obstacle to restoring Australia’s arid zone, which has suffered catastrophic biodiversity loss and is highly vulnerable to ecological collapse.

The United Nations Decade on Ecosystem Restoration, which began in 2021 and runs to 2030, is gathering pace. The initiative is a rallying cry for the protection and restoration of global ecosystems to benefit people and nature and mitigate climate change and biodiversity loss. Australia is in a unique position to become a trailblazer in ecological restoration on a vast scale by considering the decommissioning of the Dog Fence as it’s known in SA. With plans afoot to extend and reinforce the fence and increase stocking levels within its marginal grazing lands, the UN initiative provides impetus for Australia to reconsider the fence’s existence.

At 5614km, the Dog Fence is the longest barrier fence in the world. Built to keep dingoes out of grazing lands, its construction began in 1946 and was completed during the 1950s, when disparate existing fences were joined up. It’s a wire-and-wood structure separating eastern Australia’s sheep country, inside the fence, from the north and west of the continent, which is outside the fence.

It was constructed during a postwar era when monoculture farming operations were expanding globally and agricultural production was intensifying. Widespread use of pesticides and other pest controls were turning otherwise marginal country into productive agricultural land, providing cost-effective farming but with little under- standing of the environmental consequences.

While the term Dog Fence is commonly used to refer to the structure, the terrain it traverses is so remote and arid that conditions are far too extreme for the survival of any domestic or feral dog. The canines existing here are desert dwellers – dingoes that have evolved for more than 4000 years to live in this environment.

At 1.7m high, the fence is tall enough to prevent the movement and dispersal of most medium-to-large terrestrial native wildlife – kangaroos, wallaroos and emus – and introduced species such as feral horses, goats, camels and pigs. It functions as one element in an arsenal of dingo-exclusion methods that have helped the sheep industry survive in the arid and semi-arid lands immediately inside the fenceline, and in the higher rainfall sheep-wheat belt that reaches all the way to the south-eastern seaboard.

Dingoes that reach the barrier tend to run along it looking for gaps, rather than trying to cross over it, so baits and steel traps with padded jaws are placed along its base: there are records of 8000 to 26,000 baits laid each year along the SA section alone. Inside the fenceline, dingoes are targeted with broadscale aerial and ground baiting involving hundreds of thousands of meat baits per year. There is also a 35km buffer zone – the Dingo Sink – outside the fence designed to eradicate animals before they approach the barrier.

This predator management program has proved indispensable to the survival of the sheep industry, largely removing the dingo from areas immediately inside the fence, but it presents a unique set of ethical, cultural and ecological challenges.

While the term Dog Fence is commonly used to refer to the structure, the terrain it traverses is so remote and arid that conditions are far too extreme for the survival of any domestic or feral dog. The canines existing here are desert dwellers – dingoes that have evolved for more than 4000 years to live in this environment.

The Dog Fence crosses deserts, inland salt lakes, the Maralinga nuclear site, the RAAF Woomera Range Complex, and gas and uranium mine sites. It traverses three states, runs through the Traditional Lands of at least 23 Aboriginal language groups, 13 of which are now sleep- ing, while six are endangered. It cuts straight through mura – ancestral pathways that connect campsites, water sources and hunting grounds.

The fence begins near the Queensland coast and travels west, roughly tracing the Murray–Darling Basin’s upper reaches. At the New South Wales border, it scythes through the arid landscape of the Channel Country and follows the oldest path of the original state corner fence to join the SA border with the Queensland–NSW border fence. The architect of this massive project, which began in the 1940s, was SA sheep magnate Byron MacLachlan. He lobbied the SA government to construct the barrier, with its maintenance to be supported by a fence tax imposed on local pastoralists.

The jagged trajectory of the SA fence traces the very outer reaches of the largest sheep stations, four of which belonged to MacLachlan. The wealthy pastoralist eventually owned 17 stations, totalling more than 30,000sq.km.

Laws were imposed to protect the barrier with jail terms of three months for leaving a crossing gate open and six months for damage or removal of part of the structure. These penalties originally introduced in 1946 are still active.

Maintenance of the fence is a tri-state project involving the NSW Border Fence Maintenance Board, the SA Dog Fence Board and the Wild Dog Barrier Fence Panel in Queensland. It costs about $10 million in upkeep each year, funded by state and local governments, and a fence tax paid by graziers. The entire bill is picked up by various governments in relief packages whenever an environmental disaster impacts the region. Teams of fence maintenance officers and workers and a battalion of heavy machinery – including amphibious vehicles, bulldozers, graders, loaders, trucks, trailers and four-wheel-drive utes – keep the fence intact.

The role of the dingo as an apex predator in the Australian environment is widely recognised as an essential ecosystem service. Research during three decades by University of NSW biologist Professor Mike Letnic has highlighted the impact of dingo control on local ecologies.

He’s focused on the NSW Western Division, the central region of marginal grazing lands that is extremely vulnerable to disruption. Here, the local ecology is highly specialised with many endemic species.

Since the mid-1800s, land clearing, pest-control measures and the influx of sheep have resulted in the extinction in the area of 24 of the 61 native mammal species, with another 17 listed as endangered. Mike’s research has revealed differences in mammalian assemblages either side of the Dog Fence.

Small mammals (less than 7kg) thrive in areas where din- goes are present and, conversely, numbers of large herbivores explode where there are none or few. “It’s never a straightforward process,” Mike says. “Where there are dingoes, there are more small mammals and this includes rabbits, perhaps because there are fewer foxes.”

Where there’s an overabundance of foxes, goats, cats and kangaroos inside the fenceline, however, some ecologists argue the reintroduction of the dingo would benefit the environment, enabling grasslands to regenerate and promoting biodiversity.

Sheep production in in the marginal grazing lands, an area of 820,000sq.km, or 11 per cent of the continent, relies entirely on dingo eradication to survive. However, sheep numbers in this region have fallen by more than 75 per cent since 1991, due to market forces and the effects of climate change. Demand for ethically produced goods such as predator-friendly and organic meat has also grown.

Research into decommissioning the Dog Fence and moving the stock protection zone further south could provide a sound economic alternative for the region while allowing marginal grazing lands to regenerate. The fence certainly protects sheep and the wider pastoral industry from dingoes. But it also presents a hazard to native terrestrial wildlife and disrupts ecosystems. Entrapment in the wires affects marsupials, birds, bats and reptiles, and fence hanging is a common threat, particularly to kangaroos.

A loss of connectivity between the arid interiors and the Murray–Darling Basin has affected the dispersal and survival of terrestrial wildlife, and prevents free movement in times of drought, flood and fire. Emus range across hundreds of kilometres in search of water and food sources. They get trapped and disorientated when they reach the barrier, sometimes running the fenceline until they veer off or die of exhaustion. They have been slaughtered along the fenceline by the thousands in times of drought because it’s considered more humane than leaving the animals to die of dehydration and starvation, while also preventing damage to the structure. Similarly, large numbers of kangaroos die or must be culled when they are unable to disperse during dry times – this is particularly problematic in bottlenecks and corners of the fence, such as in Sturt National Park, in the arid far north-western corner of NSW.

Emus are long-distance dispersal vectors for seeds and spores, carrying large seeds in their gut for more than three months across hundreds of kilometres. The Dog Fence limits their ability to disperse seeds over large areas, causing a critical loss to vegetation diversity, floral health and genetic transfer.

The NSW Western Division is almost entirely Crown Land and currently carries just more than 2 million sheep – about 25 per cent of actual capacity according to the expectations of Crown Land stocking rate figures. It’s been identified as the environment at highest risk of total ecosystem collapse in Australia.

These lands have been described as a dustbowl and conservation wasteland. But this country wasn’t always like this. Early explorers described the Western Division grasslands as expansive, with mature stands of trees lining the banks of the Darling River. Banksias – now locally extinct – grew on the dunes, stabilising soils and supporting nectivorous birds that have not been seen there since the 19th century. Native bronzewing pigeons filled the skies in flocks so large they darkened the sky. They are now listed as endangered in the region.

Before European arrival, the lands supported a large variety of food sources adapted to the region’s extreme heat and unreliable rains. These included perennial wild tomatoes, dry season wild onions, bush potatoes, wild orange, emu apple, bush lemons and bananas, quandong and a plant that stored water in its root system called tjunkul-tjunkul. These, along with the staples of yam daisy, wood duck, malleefowl, red kangaroo, emu, witchetty grubs and reptiles provided well for Aboriginal communities.

Dingoes live on in Dreaming stories, even though they have largely been eliminated from Traditional Lands just inside the fenceline. Urdninyi (wild dingoes) and wilka (tame dingoes) lived in the Flinders Ranges with the Adnyamathanha people for thousands of years, and they remain totemic animals included in local kinship systems. In NSW, the dingo is central to the cosmology of the Barkindji, the First Nations people of much of the Western Division.

Sheep were moved onto the marginal grazing lands in the 1860s. Within 20 years the vegetation was depleted, the drought refuges were cleared and wildlife was in rapid decline. Perhaps the most comprehensive records of these changes are illustrated in the diary entries of naturalist and grazier Kenric Harold Bennett (1835–91). The Bennetts moved onto the lands of the Wiradjuri in the early 1860s, setting up Moolbong and Yandembah stations near what is now Hillston in Central NSW.

They sank wells, moved Traditional Owners off the lands, and brought in sheep in their thousands. By 1887 Bennett observed that many bird and mammal species were disappearing. “Species that were formerly numerous have for many years past entirely disappeared: others that were numerous during certain portions of each year are now represented at long and uncertain intervals by a few stragglers,” he wrote. He shot and preserved the last sighted eastern hare-wallaby that had once been one of the most common species on the plains but is now officially extinct.

Sheep-stocking rates in the Western Division in 1860 were about 350,000, climbing to a staggering 13.6 million in 1891. By the start of the Federation Drought in 1895, the ecosystem was set up for total collapse, and that’s exactly what happened.

By 1901 the marginal grazing zone was overwhelmed by financial ruin and littered with bank foreclosures and abandoned properties. According to Canberra’s National Museum of Australia, farmers walked off an estimated 5 million acres (20,200sq.km) of Crown leases in the Western Division. The widespread and severe environmental degradation caused calamitous sandstorms across Australia’s south-east. The decline in available water resulted in contamination and poor sanitation, followed by outbreaks of potentially deadly conditions such as heatstroke and dehydration, plus epidemics including typhoid, diphtheria, enteric fever, influenza and dysentery. Many people died, and an estimated two-thirds of the sheep flock starved or died of dehydration as prices for livestock were reduced to “virtually nothing”.

The UN Decade on Ecosystem Reconstruction aims to foster large-scale restoration programs, addressing the degraded, damaged and destroyed lands that have triggered a biodiversity crisis worldwide. Regaining ecosystem functionality is the goal, to help mitigate climate change and prepare for increasing vulnerabilities across arid and semi-arid regions.

Moving away from monoculture management in these marginal grazing lands presents a unique opportunity to invest in transformational mosaic restoration projects that connect water sources and protected areas with areas suitable for sustainable human and agricultural use. This would help restore biodiversity, and encourage ecological and cultural renewal, with the potential to provide mitigation and adaption to climate change.

Currently NSW has allocated $37.5 million in public funds to extend the Dog Fence, building an extra 742km around the north and western reaches of the Western Division. SA is similarly spending $25 million rebuilding and reinforcing their section of the fenceline. These projects represent a significant investment in the region’s future, funding that could go a long way towards researching and developing sustainable land uses, such as traditional and organic crop production, predator-friendly livestock production, solar energy farms, and the regeneration of native grasslands. This could potentially improve food security and public health outcomes for the entire region.

We spot some wild goats as we fly over the Flinders Ranges. A few small flocks of sheep and cattle are visible during the first half-hour in the air, but after that the airspace and landscape are solely our own. There are no signs of birds or terrestrial life for the next five hours.

We head up over the former coalfields at Leigh Creek and across the Oodnadatta Track. Over the southern reaches of Kati Thanda-Lake Eyre, camel tracks imprinted into the briny, shimmering salt flats are the only signs of life.

We refuel at William Creek. On the homeward stretch, the pilot flies in low over the fence for a few kilometres where it bisects Billa Kalina, a cattle property within the RAAF Woomera Range Complex. Here, it’s an ageing wire mesh structure. The posts are irregular. Some are made of wood, or from simple tree branches, with the occasional metal post propping up a tangled web of chicken wire and steel mesh in layer upon layer, tracing the rise and fall of the undulating desert dunes.

The Cessna skirts the eastern edge of the crystalline surface of Lake Torrens before we head back to the airstrip. The landscape here takes my breath away. It’s winter, a clear, still day with rainless clouds rolling over the mountains.

I didn’t spot a single dingo, kangaroo, emu or, in fact, any wildlife on the entire journey, other than those goats and the camel tracks.

Removing the Dog Fence and relocating 6 per cent of the nation’s sheep flock away from these fragile lands would open up 820,000sq.km for ecosystem restoration, which would promote cultural and ecological renewal on a vast scale.

The unique biodiversity that lives here and in the heart of Aboriginal cosmology, including the dingo, is extraordinary and worthy of every inch of our consideration.

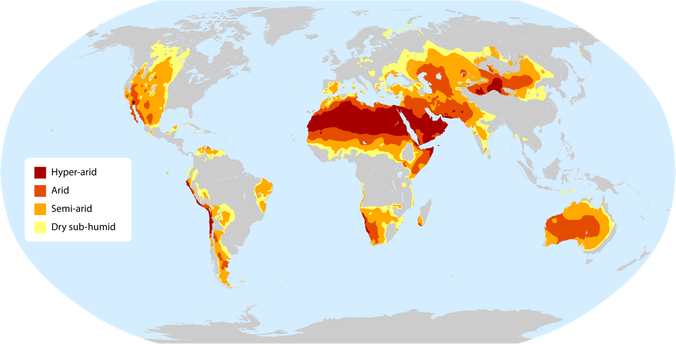

Drylands

These are areas that experience great water scarcity. Covering 41.3 per cent of Earth’s land surface, they are home to 2 billion people. They are extremely vulnerable to climatic variation and human activities such as deforestation, overgrazing and unsustainable agricultural practices. The consequences of such actions include soil erosion, loss of soil nutrients, changes to soil salt levels and disruptions to carbon, nitrogen and water cycles. Drylands are described by the Food and Agricultural Organization (FOA) of the United Nations as vital to the stability of Earth’s environment, playing a key role in the balance of atmospheric elements, and in the reflection and absorption of solar radiation.

These regions support a uniquely adapted ecology as well as desert peoples and cultures. With climate change these areas and communities are increasingly vulnerable, but also hold the key to adaptation.

Projects such as the African Forest Landscape Restoration Initiative (AFR100) promote the restoration of vast dryland ecosystems. AFR aims to restore 1 million square kilometres of deforested and degraded land in Africa by 2030. The goal is to promote food security, mitigate climate change, and alleviate poverty.

The crisis driver in Australia’s drylands is not poverty or hunger but monoculture – the most prevalent global model for the production of food, fibre and wood.

Environmental historian Professor Frank Uekötter, from the UK’s University of Birmingham, attributes the success of monoculture to three factors: they operate at scale, produce a single product and cater to distant markets. “This is despite plenty of empirical and theoretical evidence that monoculture is a really bad idea,” he says.

Professor Uekötter points out in his research that the reliance on monoculture systems of production is our default position for agriculture, but we have never tried any other way on a large scale. Certainly there is a place for monoculture, but perhaps that should be in concert with diverse agricultural systems, not to the exclusion of them.

Find out more about Frank’s research into monocultures here: A Global History of Monocultures.