Monsters or masters of the deep sea?

How deep can fish live in the ocean? That question has captivated me for more than a decade. But my research team’s discovery of the deepest sea fish, announced recently, might not be the final answer. There may be more.

How deep – and how strange – remains open for debate.

Last year, my colleagues and I went on an expedition to the deep trenches around Japan. Having already found the Mariana snailfish in 2014 – thought to be the deepest ever – we had a hunch that with more exploration and a better understanding of things like temperature, the Japanese trenches would host a fish at even greater depths.

After another 63 deployments of our deep-sea cameras, bringing our total to about 250 across the globe, we hit the jackpot.

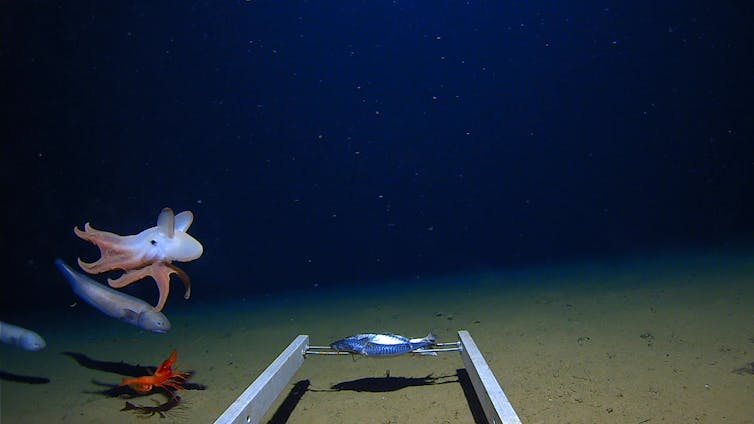

We found what is likely a new species of fish in the Izu-Ogasawara Trench and filmed it many times at depths between 6,500 and 8,000 metres. Then, at a staggering 8,336m, a rather unassuming little juvenile slowly swam past the camera, oblivious to the fact it had just become the deepest fish on record.

Much more than monsters

If you ask someone what the deepest fish in the world looks like, they will probably conjure up an image of a scaly, black, stealthy creature with bioluminescent lures, large fangs, spiny fins and demonic eyes lurking in the depths waiting to strike at unsuspecting victims. It would be nothing like the shallow-water fish we eat, keep as pets, or pay to see in aquariums. It would be more the stuff of nightmares.

While these sorts of visually striking creatures do exist, they are often not that deep, or that big. Hatchet fish, fangtooth, lanternfish, dragonfish, viperfish and angler fish inhabit the mid-waters of the twilight zone (less than 1,000m deep). Many of these classically spooky monsters are actually very small and are simply enlarged in our imagination, in the absence of any sense of physical scale.

The black body, big eyes, bioluminescent lures and unfamiliar fins and textures are all adaptations to stealthy but efficient living in low-light conditions.

At deeper levels, where low-light adaptations are no longer required (because there’s a total absence of light), marine life takes on different, less dramatic forms. Adaptations to depth, or rather high pressure, are not usually things we can see, but rather changes at the level of cells or body tissues, to enable life at depth.

If we take, for example, the deepest fish, the deepest prawn, the deepest jellyfish, the deepest anemone and the deepest octopus, we find them at depths of 8,336m, 7,703m, 10,000m, 10,900m and 7,000m, respectively (between 4.3 and 6.8 miles deep).

The deepest of the deep

The deepest fish in the world isn’t really a deep-sea fish. They are snailfish in the family of ray-finned fishes called Liparidae. There are more than 400 species of snailfish, and most are found in shallow waters, or even estuaries in some cases. This family of fish has adapted to an array of different environmental settings and habitats, including the deepest.

We found the deepest of all in the Izu-Ogasawara Trench at 8,336m, but this fish does not conform to any preconceived visual impression of what the deepest dweller should look like. They are in fact small, translucent pink, quirky little fish that swim like tadpoles and would not look out of place in a sunlit lagoon.

Similarly, if we look at the deepest of the big crustaceans, which happen to be penaeid prawns (Benthesicymus), there is nothing all that unfamiliar about them. The can be up to a foot long, strikingly red in colour, and swim and behave in exactly the way one would expect a prawn to swim and behave in our coastal regions. It would not look out of place at the local fish market.

The deepest jellyfish looks like a normal jellyfish. The deepest anemones can be found attached to rocks at the very bottom of the Challenger Deep, the deepest place on Earth. These as yet unknown species are attached to rocks that filter food out of the water. They appear more plant-like, resembling delicate and beautiful flowers swaying in the wind.

And then there is the octopus, an animal that has haunted sailors for centuries. In contrast, the newly discovered species of Dumbo octopus (Grimpoteuthis) is a small and cute little cephalopod with fins that resemble big ears (as in Dumbo the elephant). The species was filmed nearly 2,000 metres deeper than any other octopus or squid at a depth of nearly 7,000m. https://www.youtube.com/embed/OX7w5EcDX9o?wmode=transparent&start=0 A guide to the Dumbo octopus, from Deep Marine Scenes.

The true masters

Essentially, dark-sea creatures in the upper ocean detract from the real deep-sea creatures, giving us a false impression of the natural aesthetic of this community.

While the dark-sea animals have adapted to low light in a way that jars our imagination, the true deep-sea animals represent more of a case of where the wild things aren’t.

The snailfish are the true masters of the deep, not monsters of the deep. If we are to ever truly understand the ocean, and appreciate it as the largest habitat on Earth, we should retrain our brains and realise that even thousands of metres underwater, there are populations of little fish just going about their daily business.

Alan Jamieson, Founding Professor of the Minderoo-UWA Deep-Sea Research centre, The University of Western Australia

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.