This scientist deliberately subjects himself to the world’s most painful stingers

“I’m interested in what the chemicals are behind pain and how they interact with our bodies to create that pain,” Dr Sam Robinson explains to me in a casual, nonchalant tone.

But there’s nothing nonchalant about the way Sam explores his interest.

A molecular biologist at the University of Queensland’s Institute for Molecular Bioscience, he has earned himself quite a reputation for his unconventional research methods, namely, for being stung by the world’s most painful insects and plants, on purpose.

“I’m genuinely interested,” he tells me. “I find something and I wonder ‘what does that sting feel like?’ and there’s often no information on that, or no good quality information.”

Sam rates each sting using a pain scale developed by the late American entomologist Dr Justin Schmidt, who was famous for his studies of stinging insects.

While Schmidt’s stings weren’t intentional, they were inevitable in his line of work.

“He worked with these insects for 40 years,” says Sam. “So if you’re working with them for that amount of time, you get stung, there’s no way around it!

“He was the first one to start recording the different experiences and he made this key observation early on that not all stings are equal. So he developed this pain scale called the Schmidt Sting Pain Index.”

While the science behind each sting is complex, Sam’s methods for recording his (painful) experiences are a humble notebook and stopwatch.

“Obviously I’m writing down the intensity of the pain and how long it lasts, but also the type of pain and other symptoms, like inflammation.”

Not only is Sam documenting the effects of different stings on the human body for scientific record, his observations have the potential to lead to significant biomedical applications.

“One of the cool things it can do is by finding new things and new targets in our own bodies, in terms of our pain-sensing neurons, we can potentially develop a new class of drugs to target that,” Sam says.

“If you can understand, at a molecular level, why something stings when it hurts then you can potentially come up with a more rational treatment for that.

“A new class of painkillers would be the ultimate health outcome.”

But while new medications may be a while off, Sam and his colleagues have already had myriad scientific breakthroughs.

“The progress has been unbelievable actually. We’ve had some really amazing outcomes over the last five years or so.”

In May this year, Sam and his team published a paper in Nature Communications, revealing for the first time that ants inflict pain with neurotoxins.

“I looked into the venom of green ants, along with a bunch of other ants, and found that this particular class of toxin was responsible for the pain,” explains Sam. “And this toxin class was new to science.

“So, for one, we didn’t know that’s how ants were causing this type of pain, and then, also, no one knew this class of toxin existed!

“We figured out what the toxins target in our nerves and that information is very, very useful to understand how this works at a molecular level and how it’s involved in pain.”

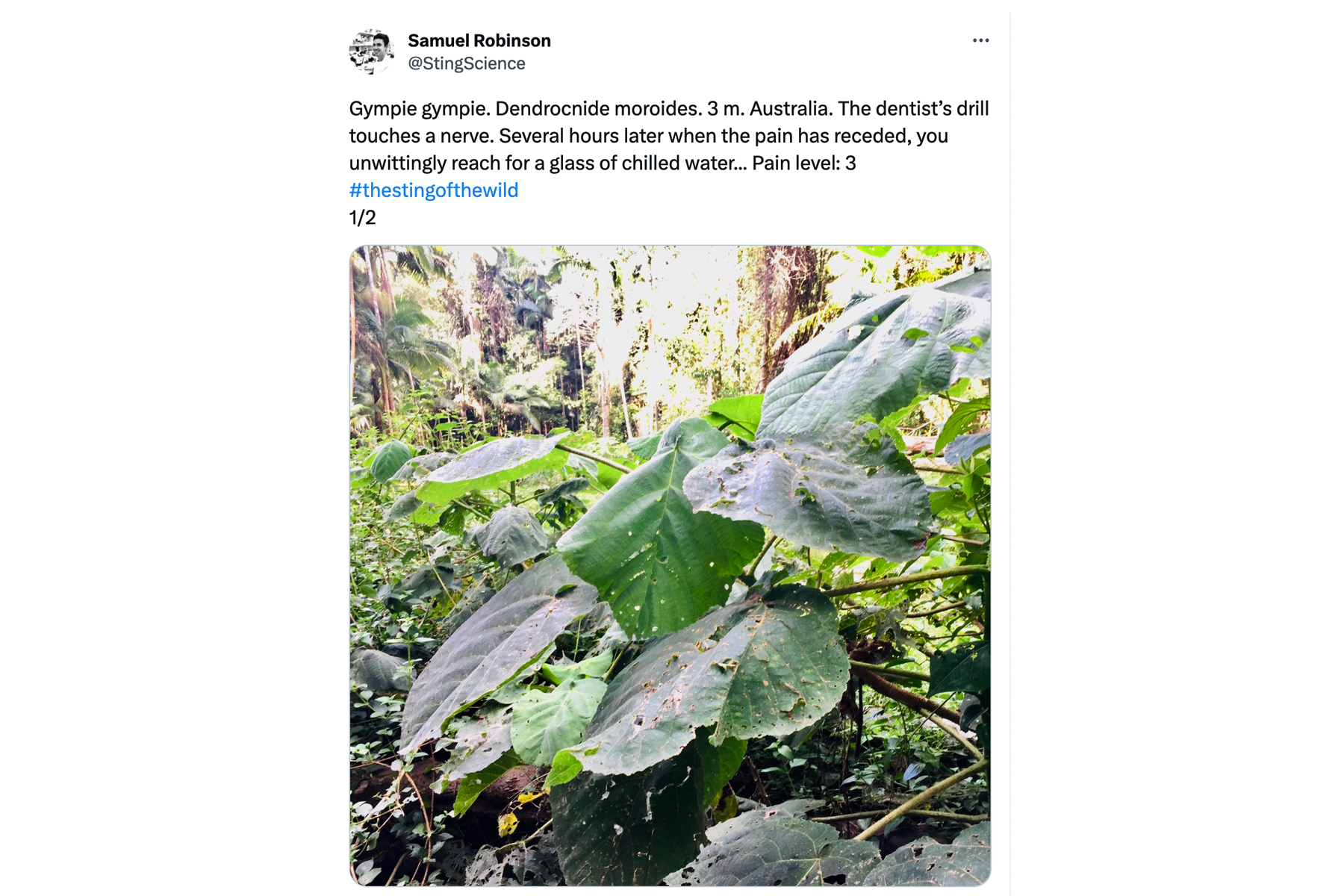

Another massive breakthrough, published in Nature Communications in 2020, was a discovery about the Gympie-Gympie (Dendrocnide moroides) plant: what scientists had long-thought caused its excruciating sting was incorrect.

“For a long time people thought that the long-lasting pain was because of the little spines from the leaves or stems stuck in the body – like fibreglass. But we now know that that’s not the case because we’ve figured out what the toxin is in those stinging trees, and how it causes pain,“ says Sam.

A common remedy for the infamous Gympie-Gympie sting is to use sticky tape or wax to remove the tiny stinging hairs from the skin.

“We now know that’s completely futile because it’s the toxin that’s causing this long-lasting pain, it has an irreversible effect on your nerves,” Sam explains.

“It targets something in our nerves that we didn’t know was involved in pain and now we know this particular protein is intricately involved in a certain type pf pain.”

“So that’s just two examples of new things we’ve learned.”

Most painful stings

The late Dr Justin Schmidt rated the bullet ant (Paraponera clavata) – found in Central and South America – as having the most painful insect sting in the world. Sam agrees.

“It’s called a bullet ant because apparently it feels like being shot,” says Sam. “Now, I don’t know what being shot feels like, but its bite is a really unique pain, a very deep, drilling, long-lasting pain. It can last for 12 hours, it’s quite amazing.

“It’s the most intense pain I’ve felt from a sting and the length of it just wears you down so that’s what gives it this really high rating.”

Luckily, we don’t have bullet ants in Australia, but Sam says our green ants (Rhytidoponera metallica) give the bullet ants a run for their money.

“It’s a unique sort of pain, that can gradually build and then last quite a long time. It can be quite intense and quite deep.”

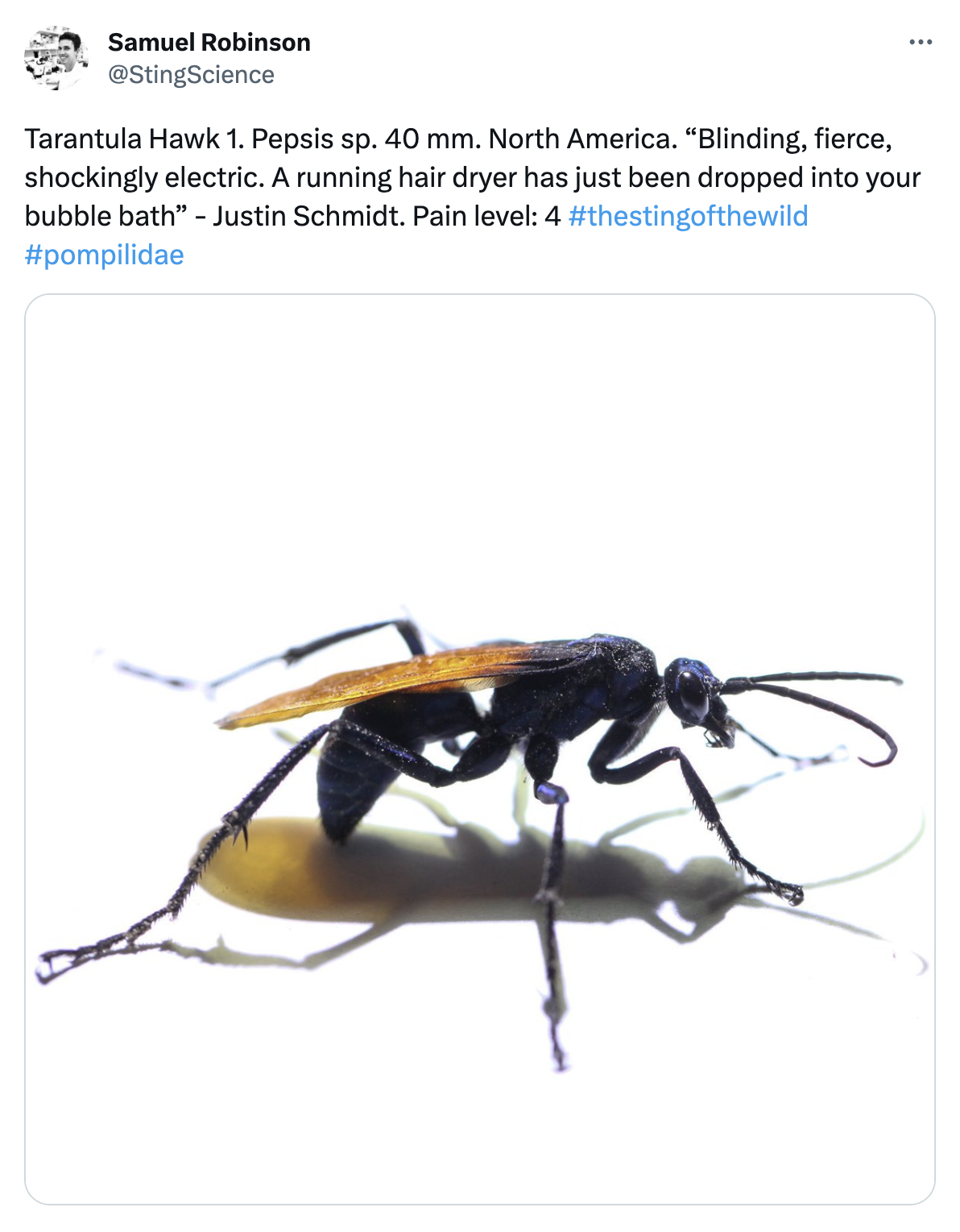

Also high on Sam’s list of most painful stings is one from, what he calls, the “humungous” tarantula hawk wasp (Pepsis sp.).

“They are just monsters, they can be a couple of inches long, quite frightening, and they have no natural enemies – I think that’s because everything knows that when they sting it just hurts so much!

“When you’re stung it’s five to 10 minutes of intense pain and swelling.”

Like the bullet ant, the tarantula hawk wasp is not found in Australia, but, again, we have an equivalent: the spider-hunting wasp (Heterodontonyx bicolor).

“This sting is right up there with the tarantula hawk wasp,” says Sam.

Chatting to Sam as he relives these horrid encounters, there‘s one question I just have to ask: “Is it worth it?”

“Yeah,” he says without hesitation.

“These things, they’re not going to kill you. People are really worried about stinging things but the reality is, that for 99.9 per cent of us, they’re just going to cause a bit of transient pain. They’re not going to do you any harm beyond that.”