Defining Moments in Australian History: Penicillin breakthrough

Before antibiotics, a scratch – even a small one – could be fatal. Every year, countless people died as minor wounds – blisters, cuts and scrapes – became infected with streptococcus and staphylococcus bacteria. Treatments were also limited for bacterial diseases such as typhoid, syphilis, tuberculosis and pneumonia, which claimed thousands of lives each year.

In September 1928 Scottish bacteriologist Alexander Fleming returned to St Mary’s Hospital Medical School in London after a holiday. Before leaving, he’d left some petri dishes containing staphylococcus bacteria to soak in detergent. When Fleming returned he noticed that one dish that had not been covered by detergent had become contaminated with mould. The particular mould, Penicillium notatum, seemed to produce a substance that killed the bacteria around it. Further tests confirmed the antibacterial properties of the substance, which Fleming called “penicillin”.

Because he was unable to extract and purify the active component in penicillin, Fleming couldn’t produce anything medically useful from what he observed. He published an article about his discovery and its potential in The British Journal of Experimental Pathology before pursuing other research interests.

Ten years later, Howard Florey, an Australian scientist working in England, brought together a team of research scientists (including Ernst Chain) at Oxford University’s Sir William Dunn School of Pathology. The team was looking for a new project, and, after reading Fleming’s article, Chain suggested penicillin. Assisted by biochemist Norman Heatley, the Oxford team tried to separate and purify the active components of the mould.

Extraction was difficult and initially only tiny amounts of penicillin were harvested. The team worked continuously on developing processes to grow and harvest penicillin more effectively, even using bedpans as vessels to hold a protein mix that grew the mould spores. After a while there were rooms in the school full of penicillin-producing mould; however, the output was not high enough to complete widespread trials of penicillin.

Eventually, after successful tests in mice, the team began treating patients at John Radcliffe Hospital. Initial results were mixed, but with time the trial process was refined and penicillin proved to be extremely effective at treating bacterial diseases and infections that had once been fatal.

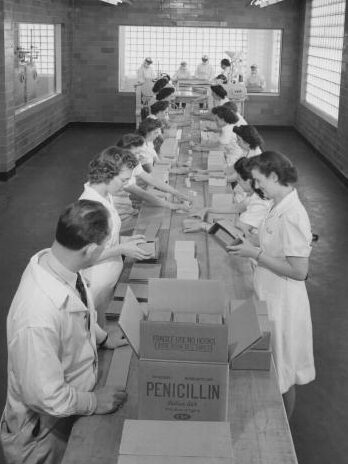

in the mid-1940s. Image credit: Getty Images

With the onset of World War II, Florey and his team were driven by a single goal – to ramp up penicillin production for widespread use. But despite the potential of its “wonder drug”, the Oxford team was unable to get enough support by 1939 to begin large-scale manufacturing and testing in Britain. But in 1941 the US government agreed to begin producing penicillin at a laboratory in Peoria, Illinois.

Further research discovered new strains of penicillin that would provide higher outputs and make enough quantities of the drug for all Allied troops. The best strain was found growing on a rockmelon at a farmers market. US pharmaceutical companies, including Pfizer, soon began producing penicillin, and by the latter half of 1944 the drug was in common use.

Penicillin saved thousands of lives during WWII and is widely considered a contributing factor to Allied victory. After the war, the drug became available to the public and was used to treat a variety of common infections and illnesses. The development of penicillin led to the discovery of various antibiotics that are still used today. Penicillin also made possible many innovative advances in modern surgery, such as skin grafts and organ transplants.

In 1945 Fleming, Florey and Chain jointly received the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine. Howard Florey has also been recognised many ways in Australia. A Canberra suburb is named after him, and between 1973 and 1995 he featured on the $50 note. There are also a number of university research schools and fellowships named in his honour.

‘Penicillin breakthrough’ forms part of the National Museum of Australia’s Defining Moments in Australian History project.