In the autumn of 1982, Tasmania Parks and Wildlife Service (PWS) ranger Hans Naarding was birdwatching near Togari in the state’s far north-west.

After a tiring day in the field, he parked his LandCruiser near a crossroads to sleep. At about 2am, with rain thrumming on the thickly forested landscape, something woke him, and he pointed his torch out into the night.

“When I opened the window, the rain just poured in, and I shone the spotlight around at the end of the [torch] beam. Sure enough, it was a thylacine, right in front of the car, ” Hans told The Mercury newspaper, many years later.

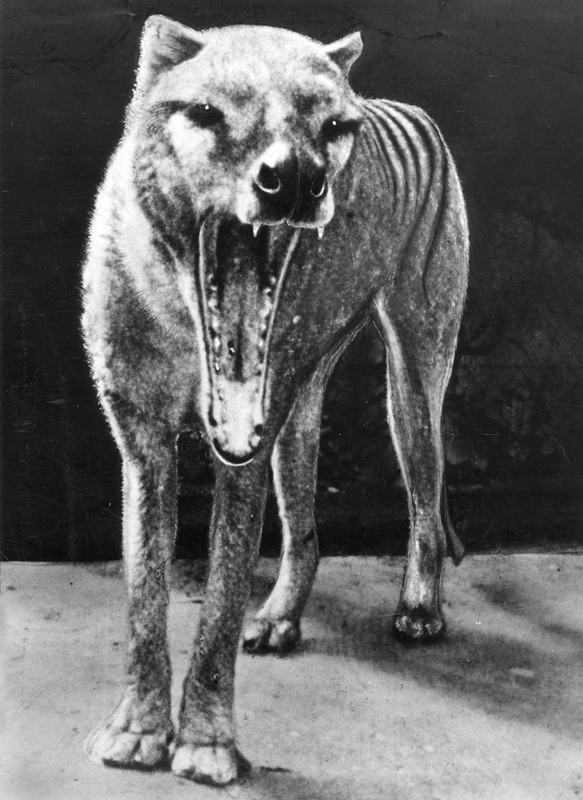

Hans’s camera was out of reach, so he instead focused his efforts – and channelled his many years of experience observing wildlife in Africa and Australia – on mentally documenting the encounter, which lasted for about three minutes. He described a full-grown male, 6–7m from the vehicle, which for a period even held his gaze before it slipped off into the inky blackness.

“He was sopping wet…I estimated his weight, counted his stripes on his back, and I could see it was a very healthy male,” Hans recounted to the newspaper.

Given his extensive wildlife experience and expertise as a ranger, his sighting is regarded as one of the most credible of the past 40 years, with the then director of the PWS, Peter Murrell, describing it as “irrefutable and conclusive”.

It would lead to a year-long, but ultimately fruitless, search by PWS rangers in the region for any further hints of the presence of the marsupial carnivore.

“This was someone who knew Tasmanian wildlife and was unlikely to have made an error,” says Barry Brook, professor of environmental sustainability at the University of Tasmania (UTAS) in Hobart. “So no-one ever really knew what to make of that sighting.”

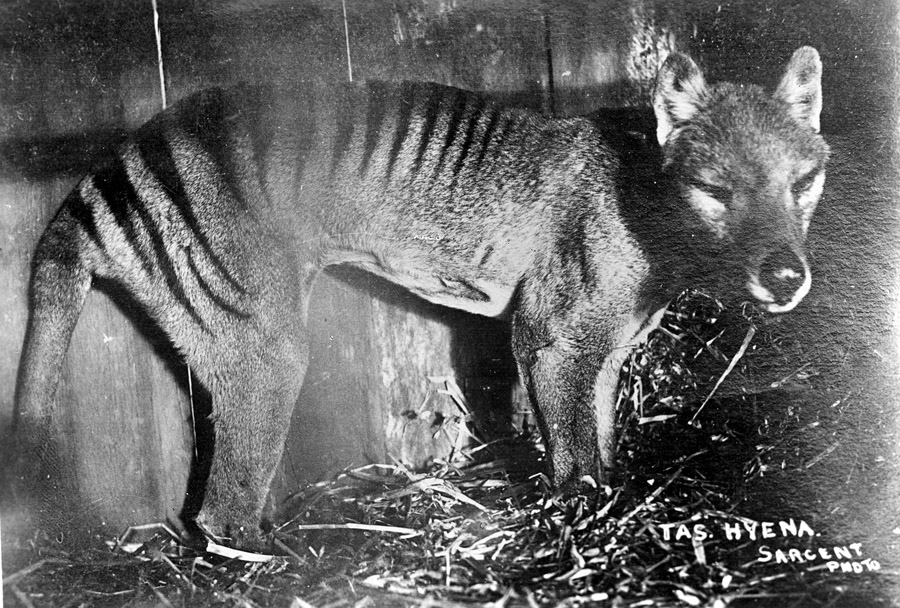

While Hans’s account seemed highly credible, the popular consensus on the topic of the Tasmanian tiger has been that it went extinct in the wild at some point in the decades following the demise of the last captive individual at Beaumaris Zoo in Hobart on 7 September 1936.

That date is when we observe Threatened Species Day in Australia, and the thylacine was officially declared extinct by the IUCN 50 years later, in 1986.

The thylacine’s story didn’t, however, end in 1936. Although reports of it in the wild had dwindled since the early 1920s, other credible sightings continued to be reported by fur trappers, bushmen, scientists and other reliable experts well into the 1960s.

There has been no hard evidence to corroborate all these sightings. But a new, incredibly thorough, statistical analysis of more than 1200 reported sightings and other data has, for the first time, mapped the decline and extinction of the species, concluding that the thylacine likely did survive in tiny numbers in wilderness areas until the 1980s.

The study, led by Barry and his team at UTAS – and including co-authors from the UK, USA and France – was published in the journal Science of the Total Environment in March 2023. The rigour of the work has been widely lauded by conservation scientists.

This remarkable proposal not only gives credence to Hans’s 1982 account, but also leads to an inescapable truth, that, albeit at very low numbers, the thylacine may have continued to pace a few cool, damp patches of the wilderness during the lifetimes of many people who are alive today.

“That [1982] sighting sparked a massive search. Everyone who heard it was convinced it was true, so the results of this new study seem perfectly plausible to me,” says Jack Ashby, who conducts research on Australian mammals and is the assistant director of the University of Cambridge Museum of Zoology in the UK.

Jack, who was not one of the study authors, says that, until recently, remote areas of lutruwitra/Tasmania’s wilderness were largely unstudied, so could have harboured unrecorded species.

He adds, “On a personal level, the idea that I was alive, and could have been in Tasmania while the last thylacines were still alive, kind of furthers the blow of their extinction.”

A compelling case

To make the finding, Barry, UTAS research fellow Jessie Buettel and their co-authors spent five years compiling an exhaustive database of recorded thylacine sightings since 1910, when it was already becoming very rare.

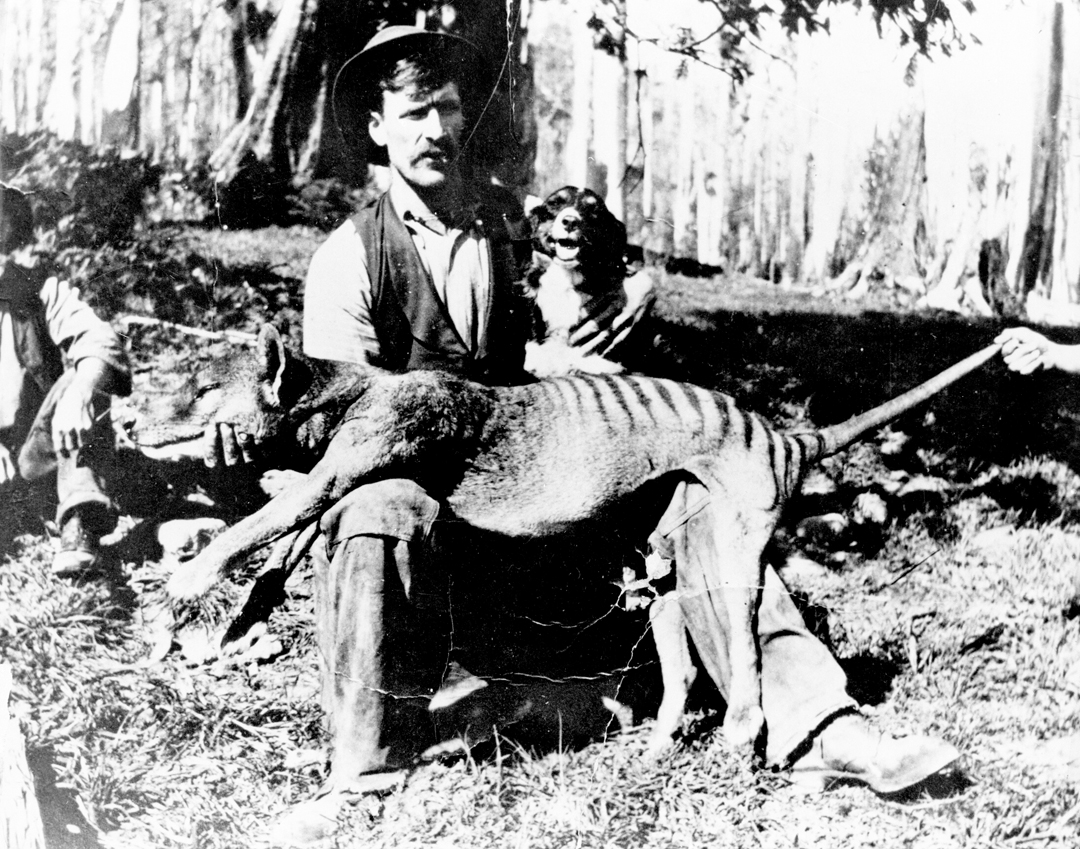

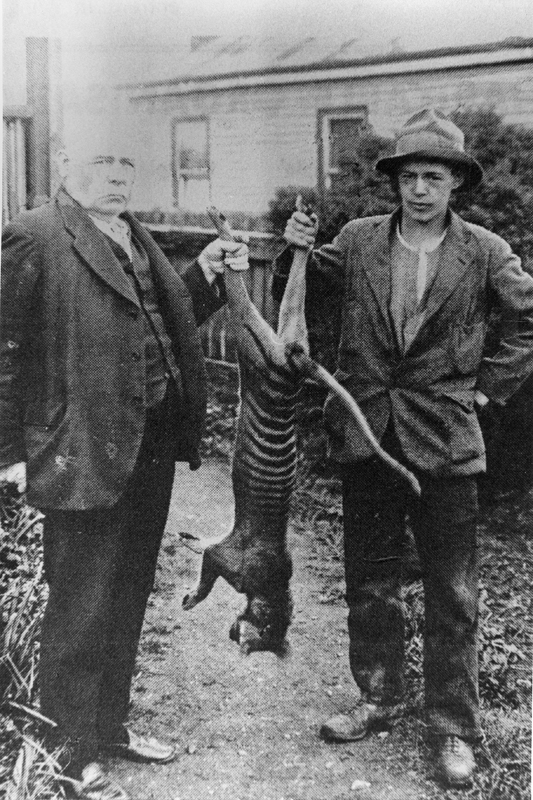

Following the period from 1888 to 1909, when government bounties were offered for dead thylacines, the authors found the species’ distribution shrank very rapidly, with the final surviving subpopulation likely to have been in the island’s South West region.

The thylacine was never present at high densities on the island, and had an estimated population of just 2000–4000 animals before European colonisation.

Between the 1830s and 1920s at least 3500 were killed by hunters, illustrating the devastating impact that human persecution had.This database includes 1237 observational records and 99 physical records, such as carcasses and skins (all of which were collected before 1936).

Barry says the number of reported sightings is vast. Many of these are likely to be misidentifications or are otherwise false. “[But] with more than half of them, you can’t just wave your hand and say ‘this is nonsense’,” he says. “You have to give them some level of credibility.”

To treat the question in a rigorous and scientific manner, the team invented a new method to deal with uncertain sightings, ranking them according to their plausibility.

“A lot of science is about measuring uncertainties, trying to narrow those uncertainties,” Barry says. “It’s a matter of looking at that whole record and saying, ‘Well, some things have high probability of being the correct observation, and some things very low probabilities.’”

The relative likelihood of sightings being accurate was ranked based on factors such as the expertise and past knowledge of the observer, and the credibility of their reports; 429 of the sightings were expert sightings, with 709 other sightings assigned less weight in the analysis.

“As you move further and further away in time from people who had actually killed those things, or captured them and sold them to zoos, or sold skins during the bounty period, you’re getting more disconnected from evidence of direct contact with the species,” Barry adds.

His team used a statistical method called “uncertainty modelling” to attempt to map out the decline and eventual extinction following 1910. This initially suggested that the species met its demise in the decades after the final individual was caught, so somewhere between the 1940s and the 1970s.

But further analysis hinted at an extinction as recent as the 1980s to early 2000s, with a small possibility that the species remains in the remote South West wilderness today.

“If I had to guess, I would say the extinction was in the late 1980s,” Barry says. “But there are plausible sightings in the ’90s and some in the 2000s. So it’s hard to know for sure, but scientifically, based on the analysis, I would say the sweet spot for those probabilities is the late 1980s.”

As the authors have noted, the modelling points to the species having persisted in “the remote wilderness of the South West and central highlands regions of the island for decades after the last confirmed specimen”.

The research is also significant because it establishes a method for estimating when other rare species have gone extinct in the wild, and for predicting the future decline of animals that are in dire straits.

“[There’s] great value in the development of this model that can now be applied to other species,” Jack says. As well as the research providing “the best answer so far of when the thylacine went extinct”, it has led to the compilation of the database of sightings and other evidence, which is free to access.

Gone, but not forgotten

In addition to the 1982 sightings by Hans Naarding, the 429 sightings that the study authors regarded as highly credible also include other fascinating anecdotes.

The last confirmed direct evidence of thylacines in the wild was one captured in 1931, but from 1936 there are reports of a corpse on the beach at Wynyard in Tasmania’s north- west.

While no photographs are known to exist, Barry says that perhaps 100 people saw the body, so it’s likely to be a true account. In 1936 thylacine footprints were recorded on an expedition to the Jane River in western Tasmania.

“There continued to be credible reports, especially from fur trappers, of people coming across them through the 1940s and ’50s,” Barry says. “One of the most interesting was Herb Pearce, who had captured specimens in the 1920s and ’30s.”

In the 1950s Pearce had told a researcher who was interviewing him that he had flushed a female and cubs out from a patch of tree ferns “about five years ago”, in an area today flooded by Lake King William. He added – heartbreakingly – that “he turned his dogs on them”.

All of these reports are pretty good evidence that the thylacine persisted in small numbers throughout this period, with “the last famous one, really, of this genre”, being the 1982 sighting.

Given that the new study has changed the calculus over the estimations of until when the thylacine persisted, could it yet remain in isolated pockets of South West Tasmania today?

The team’s statistical analysis suggested a five per cent probability, but unfortunately scientists have a very good reason for suspecting it really has disappeared.

“That five per cent – that’s not nothing, is it,” says Jack. “But the reason I don’t think they are still around – and I’m sure Barry would say the same thing – is that now there are so many camera traps in Tasmania, many of which Barry put there himself.

Literally every spot in Tasmania will have been surveyed at some point. And the odds of one not turning up on a wildlife camera, or a dashcam or a smartphone, I think is pretty convincing evidence that they’re no longer around.”

Barry concurs that his team has conducted a huge amount of camera trapping as technology has improved – more than half a million “camera trap nights” across the state – “and we never saw anything like the thylacine over four years of surveying.

So again, that’s hard scientific evidence that we’ve got every other animal you can imagine that’s been recorded in Tasmania, except those things.”

But that “doesn’t stop you from imagining or dreaming about them”, adds Jack wistfully. “Anytime I’m in Tasmania, I still turn my head whenever I drive past a firebreak. It’s extraordinarily unlikely that they’re still around. But there’s nothing you can do to stop yourself looking for them.”

Back to the future

Rather than pin any hopes on finding a live thylacine, Barry’s team is now expanding the database to include all thylacine records right back to European colonisation.

They will use this to map out habitat suitability across Tasmania, which could be useful if the thylacine is ever successfully ‘de- extincted’ through future genetic technologies, and added back to a rewilded landscape.

“Even if it is extinct, and we can never bring it back, which is likely, it was still an important element of the vertebrate community that was removed,” Barry says. “And understanding the consequences of that is really important, including how resilient or otherwise Tasmanian communities might be to invasive species, such as foxes or cats, today.”

As the new study notes poignantly in its conclusion, the fate of the final remaining wild individuals of a species that is about to vanish is very rarely witnessed by people.

“This is especially true for species like the thylacine, which ranged widely but sparsely across large swathes of the Tasmanian wilderness,” the authors write.

“The last survivors were probably increasingly difficult to detect as they became ever more wary of potentially fatal interactions with people.”