A crowd is gathering along a wide dirt road in the wilderness. Cars, trucks and mud-splashed four-wheel-drives park in a long line, one behind another. Families with young children emerge, kitted out in bright jumpers and gumboots, then backpackers and grey-haired couples wearing matching hiking boots appear. The lively throng – reaching a headcount of 170 – has signed up to take part in the Walpole Wilderness BioBlitz, a two-day event held annually in the South West region of Western Australia. People have driven to the tiny south coast hamlet of Walpole from near and far – a few have even flown interstate to learn about the Walpole Wilderness.

“We’re going to split up into groups of about 10 and survey a whole range of different ecosystems, from the forests down to granite outcrops and peatlands,” says BioBlitz coordinator Dr David Edmonds, a local vet and cattle farmer, as he addresses the crowd. “We’re looking for a whole range of different things – we’ve got expert botanists to talk plants, we’ve got invertebrate specialists for the insects, and frog experts. We’ve got all sorts of people here.”

Later, David tells me he loves watching the animated conversations between experts and citizen scientists: “These are people who just want to participate and get out there and learn more about the Walpole Wilderness.”

By the end of the BioBlitz, these citizen scientists will have uploaded 3000 images onto iNaturalist, an app that helps image takers and researchers identify a flower, bird, frog, or bit of moss.

In total, the BioBlitz images will capture more than 600 species, many of which reside nowhere else on the planet. There will be thrilling sightings of rare species, and a few images that capture devastating loss.

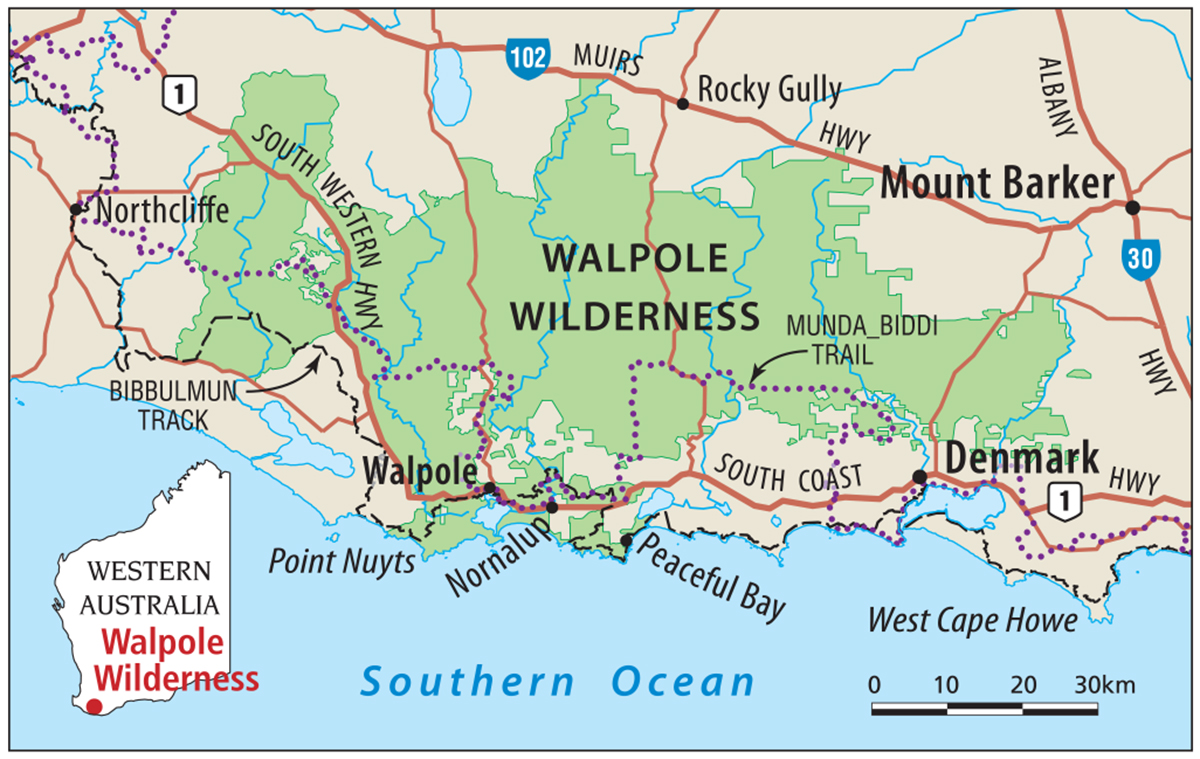

The BioBlitz occurs in wilderness that’s as untamed as nature gets. Walpole boasts the only designated Wilderness Area in Australia’s western third, consisting of seven national parks and several conservation reserves, and covering a total expanse of 3630sq.km. Driving down from Perth, many participants will sense its qualities when they enter dense forests of jarrah, giant red tingle and karri trees growing tall in a high rainfall area, or pass through a brilliant floral understorey around granite peaks, and along pristine rivers and in peat wetlands.

There’s a frisson of excitement, a contagious sense of adventure as we head out. There’s been talk of finding 40 plant species in a single tiny moss carpet on the granite rocks, locating the strange salamanderfish – a Gondwanan relic living somewhere out in ink-black lakes – and uncovering the garishly coloured sunset frog, the rarest of rare local amphibians with a technicolour tummy. But first come the practicalities. We get a lesson in treating the soles of our shoes with bacteria-killing spray – a disease called Phytophthora dieback can be carried into pristine places by the footfall of hordes. “We make sure that we have good disease control and try not to disturb the bush too much,” David says.

Our group heads off to scale a granite outcrop, only to find ourselves first trekking through a glade full of dainty flowers. Prue Anderson, one of the BioBlitz organisers, stands in the leafy copse at the foot of the rock and marks off each flower type she knows. “This is karri wattle or Acacia pentadenia; that’s bush crowea, Crowea angustifolia, the granite form, which smells incredible. There’s Taxandria parviceps, a kind of tea-tree, and a Grevillea linearifolia behind us that has another incredible scent.” She points to a low shrub covered in pretty, bright pink flowers. “That’s Boronia gracilipes, and there’s still just dozens that I don’t know.” Prue spent her childhood in this bush, even living in a tent by the Frankland River while her parents were building their home. “I left for a while but the pull was too strong,” she says, “and I had to move back with my daughter.”

It’s hardly surprising; we’re told we’re standing in a place with possibly the biggest concentration of botanical diversity in Australia; three-quarters of the South West’s 7000 plant species grow nowhere else. If any one of those species is lost from this landscape, it’s extinct.

As we walk up to the granite slope, a tiger snake is spotted by an eagle-eyed hiker. Prue calmly directs the group to let it slither out of harm’s way. The BioBlitz is aimed at inspiring the kind of curiosity and common sense that Prue exudes. “We want people who aren’t comfortable going out into the bush on their own to be immersed in it,” she explains. “[To be] comfortable being in the wild. I just think it’s the best gift that we can give ourselves, and the more you know about it, the more you’ll care about it.”

Her five-year-old daughter, Erica, has skipped up the rock face, where Professor Stephen Hopper is pointing out lizard traps and stone arrangements created and mined by Noongar people. The traps are easily spotted – metre-square rocks about 10cm thick that are propped up at one end with a fist-sized stone to attract reptiles inside. “Noongars created them to provide extra habitat for kaarda, or goannas, in particular, which are their favourite lizard food,” Stephen says. A former director of Perth’s Kings Park and Botanic Garden and the UK’s Royal Botanic Gardens in Kew, he’s now working closely with First Nations people to document plant and habitat use. “We’re so lucky here in the South West,” he says. “We’re 20m off the road and up into another world with plants and animals that have been here a very long time. And here there’s evidence of Aboriginal culture that would normally amaze people.”

As we pose for a group shot on the summit, Walpole’s seemingly pristine wilderness below reveals itself to be crisscrossed by dirt roads. “Historically, this area was used for logging, since the 1950s,” David says. “So most of these tracks are logging roads and they break the landscape up into what we call forest blocks. Here, we’re right on the corner of Soho block to the south, London to the east, Crossing to the west and, further on, Thames block.” The forest blocks hark back to an era when this wilderness was viewed largely as a timber resource to be exploited. Walpole’s Wilderness Area has been free of logging for decades, and last year the WA government announced it would stop logging in all the South West’s native forests. “These roads are now used as management access predominantly, and for us to access the wilderness and get out there,” David says. “And for managing fire.”

Our group heads out to survey one particular habitat most affected by fire. Peatlands are dotted throughout the Walpole Wilderness, waterlogged patches no more than an average 4–5ha in size. The peat itself is relatively shallow, perhaps no more than 1–2m deep, but it’s estimated to have taken 6000 years to accumulate. Handsome reed thickets of Empodisma gracillimum grow across the peatlands. Pushing through the reeds, I sense that it’s spongy underfoot; looking down, I realise I’m stepping my way over hundreds of Albany pitcher plants growing out of the dark, peaty surface. Their massed appearance is extraordinary, speckled jug-like flowers lying at our feet that trap and dissolve insects in their “pitchers” to obtain nutrients otherwise lacking in nitrogen-poor soil.

Our guide this time is Professor Pierre Horwitz, a wetland ecologist from Edith Cowan University (ECU). He wades into a shallow lake with a large net and lets out a triumphant shout when a salamanderfish is wriggling in his net. This ancient lineage of fish has not been found in these parts for 50 years. It burrows into the peat to survive summer but could disappear if dire predictions of rainfall loss in this region – a 15 per cent decline by 2030 alone – come true.

The salamanderfish would not be the only casualty. Nearly 30 years ago, Pierre was exploring a peat heathland like this one when he discovered the sunset frog (see below). Considered one of WA’s oldest frogs, the species diverged from its closest relatives 30 million years ago to form its own genus, with a unique colour scheme. Pierre was astonished by the frog’s vivid orange hands and feet and spectacular orange and blue-grey underbelly.

Like a western sunset

It was a hot summer’s day in January 1994 when Pierre Horwitz had his first memorable encounter with a sunset frog.

“I was with my research assistant Kim and we were finishing our year-long survey of peatlands in the South West,” he recalls.

They were holidaying with their families near Walpole when the pair decided on an impromptu field trip to a site they’d already surveyed three times.

“I thought I’d have a final look to make sure I hadn’t missed anything,” Pierre says.

“I reached down and put my hand into the peat, which I don’t do often. Under a peat ledge I felt something wet walk onto my hand. Instead of flicking it off, I gently cupped my hand – I don’t really know why – and brought it up.”

When Pierre unfurled his fingers, a small, dark frog lay on his palm. “Then it fell over on its back, and suddenly there was this extraordinary amount of colour.” Deep blue lower torso, light cerulean blue mid-belly, and bright orange covering its upper body. Even the frog’s hands and feet were a gold-orange hue.

“I’d never seen anything like it. I called out to Kim and said, ‘Come and have a look at this.’ We were both quite stunned.”

The researchers gingerly carried the frog back to the car, opened all the text books they’d brought along and tried to identify it.

The chance of an audience with this dapper frog is low, we’re told – viable populations have been found in only 15 local sites. Yet our luck is in again – someone hears a rapid da duk call. University of Western Australia (UWA) researcher Emily Hoffmann and Northern Territory Museum curator Danielle Edwards excitedly pinpoint the call’s location and spy a mating pair sitting in a puddle. The BioBlitz has just added another dot on the sunset frog’s survival map.

Holding the precious pair delicately in her palm, Danielle explains the two frogs are “in amplexus” – a polite word for bonking. She describes how the male glues himself to the female to prevent other males getting access while she lays her eggs. “From this part of the thumb here they secrete some kind of sticky substance,” she says. “It takes a while to bond, but once he’s stuck on, he’s impossible to dislodge. He’ll stay there for days.” We restore the sunset frogs’ privacy by retreating, but we come away with a keen sense of the importance of Walpole’s peatlands. Two weeks before the BioBlitz, these peatlands were placed in the endangered category on the federal government’s list of threatened ecological communities. The assessors listed three threats: climate change, marauding feral pigs and, at the top, “fire regimes that cause declines in biodiversity”.

The Walpole BioBlitz organisers recently launched a five-year research program with UWA and ECU to be funded by a $1.3 million grant from the philanthropic Ian Potter Foundation. Called PEAT: Protecting Peatland Ecosystems and Addressing Threats in Southwestern Australia, the aim is to pull together all information that will protect peatlands. Co-designed with Noongar Traditional Owners, it will also ascertain how cultural burning was used around peatlands in the past.

Peat expert Dr Samantha Grover, from RMIT, has flown in from Melbourne for the BioBlitz. Samantha has studied peat swamps worldwide, and says they’re incredibly rare in Australia. Walpole’s peatlands are rich and nurturing, yet nobody has mapped them all. Samantha picks up a handful of wet, black decaying matter and squeezes it; peat like this covers only 3 per cent of Earth’s surface but stores 30 per cent of the world’s soil carbon, which is twice the amount stored in the entire global forest biomass. Our group moves further into the peatlands to encounter a shocking sight. A short distance from the mating sunset frogs, Samantha confronts the aftermath of a prescribed burn that escaped control a few months earlier. The flames smouldered for days under the surface, leaving blackened pillars, or pedestals, that stick out a metre or more above the once spongy peat surface. “I nearly burst into tears,” Samantha admits. “It’s such a shock to see. Peatlands are quite resilient to fire when they’re very wet, but 50cm or so of peat has been dry enough to catch on fire. The habitat that is left shrinks. So we’re not going to find sunset frogs here.” Ironically the burn has been conducted as a fire reduction measure by the state’s Department of Biodiversity, Conservation and Attractions, which is responsible for conserving and managing the Walpole Wilderness. Pierre scoops up a handful of the dry remnants that crumble in his hand. “Peat should be spongy and moist, but after a fire you’re left with this crystalline, crunchy material. So you’ve actually done permanent damage to the structure of the soil.”

As we drive out, someone points over the steering wheel to a pristine patch of tangled wildflowers and reeds growing out of an untouched peat wetland. “They plan to do a prescribed burn through 5000ha of that in a couple of weeks,” the driver says. “They held back because we were holding the BioBlitz.”

The science exercise is coming to an end, and back at the dirt road meeting point, the different parties merge into one noisy crowd. They’re animatedly swapping stories and comparing images of threatened plants, rare mosses, an odd fish and a garish little frog. During a community curry-night dinner, photos from two previous BioBlitzes are shared on a large screen. One scientist sums up his feelings about it and the point of it all: “I still pinch myself driving along and looking at a landscape like this,” he tells the crowd. “If we document these places, they get noticed and we might just hang on to them.”

“It didn’t look like anything anybody had written about or photographed before,” Pierre says. “So it was really quite a fortuitous moment that you don’t really plan for.”

It took several more weeks before they could confirm Pierre had discovered a species new to science. “We were trying to keep the frog alive in quite warm weather over a couple of weeks while on holiday, in a hessian bag with some moss. By keeping it cool and wet, it survived happily until we got it back to Perth,” Pierre says. He was keen to consult his senior colleague, Grant Wardell-Johnson. “One very hot day, Grant came out to the university and as soon as he saw it he said, ‘This is amazing.’ We thought we really needed to take it down to the Department of Conservation staff. So we went down there and a crowd gathered! We realised this was something pretty special.” Pierre had not only discovered a new species, but a new genus – since named Spicospina after unusual spines on the frog’s central vertebrae. The species name flammocaerulea means orange-blue. Another two years passed before the sunset frog was formally described, and almost immediately classified as a species under threat. “We were able to demonstrate it had a limited range and faced declining rainfall and potentially drying and burning peats. We nominated it for listing at state and federal level, where it’s been regarded as vulnerable.” A recovery plan was drawn up, “but there’s still [much] more we need to know about how it’s going to be affected by declining rainfall and fire”.

For the common name, Pierre first thought of harlequin frog, but that was already claimed by a South American species. “It occurred to me the orange upper part and the blue of the bottom part were [just] like the western sunset. So we called it the sunset frog.”