Australian Geographic is eager to present The Weeping Tree, a series of films that see the collision of art, science, palawa connection to Country, and intimate storytelling through an iconic and charismatic Tasmanian tree that is critically threatened by the effects of climate change, the Miena cider gum (Eucalyptus gunnii divaricata).

“I’m super excited to be bringing this series of films to Australian Geographic,” says director Matthew Newton. “Film making is always a journey, and this one has been a ripper. Our small crew has stumbled through blizzards lugging heavy camera gear around the Central Highlands of Tasmania. Together we have climbed trees, fallen out of trees, crunched through iced-over puddles, spent nights sleeping in the frost and running away from feisty tiger snakes. We have witnessed stunning sunrises and sublime sunsets and been lost in the fog – always chasing the light and the stories that swirl around these magical trees.

“These films are about how individuals relate to a charismatic tree that only exists on the fringes of a few frost hollows on a heart-shaped island at the bottom of the world, lutruwita/Tasmania. I Hope The Weeping Tree will take you on a journey into the hearts and minds of people who care deeply about our world as they come to grips with big questions brought into focus by a gnarled tree that is critically threatened by the effects of climate change.”

Watch The Weeping Tree films via a playlist from Australian Geographic’s YouTube channel, and read our original story on the cider gum below.

WITH SUPPORT FROM

PURVES ENVIRONMENTAL FUND

AND

PURRYBURRY TRUST

WITH

TASMANIAN LAND CONSERVANCY AND AUSTRALIAN GEOGRAPHIC

A RUMMIN PRODUCTION

Director – Matthew Newton

Producer – Catherine Pettman

Writer – Danielle Wood, Jane Rawson (Episode 6 only)

Executive Producer – Andry Sculthorpe

Editor – Nic Venettacci

Director of Photography/Drone/Stills – Matthew Newton

Directors Attachment/Additional Cinematography/Drone/Stills – Anna Brozek

Director of Photography – Gabriel Morrison (Episode 2 only)

Camera Assistant – Rob Giudici

Color Grade / Sound Design – Michael Gissing

Graphics – Manderlee Anstice

Voice Over Recording – George Goerss, Michael Shelley, Cameron Heit

Two weeks into summer, one doesn’t expect to see snow falling in thick drifts, but in the central highlands of lutruwita/Tasmania, snow, sleet and bone-chilling gales should never be ruled out. It was this inhospitable weather that greeted us when we visited the Miena cider gums (Eucalyptus gunnii divaricata), an endangered subspecies of eucalypt endemic to the Great Lakes region.

Found up to 1050m above sea level, at the exposed edges of treeless flats or in freezing hollows, the cider gum is as hardy as they come. They prefer their feet cold and damp, favouring soil that is frost-prone and reluctant to drain. When high-altitude winds come screaming over the highlands – southerlies from Antarctica, north-westerlies from the mainland’s central deserts – the trees face them down with barely a shrug. A fringe-dweller to its core, this tree resides in the kinds of trying conditions that few can suffer. Indeed, it’s in these conditions that the cider gum thrives. This is not to say that the trees stand alone; despite the brutal conditions, a staggering degree of biodiversity encircles the gums. As we’re approaching a stand, I see huge numbers of wallabies, magpies and currawongs going about their business. A tiger snake snatching a rare moment of sun slinks under a rock, and the ground is riddled with marsupial scat. The plant life is equally impressive. Every square metre is tightly packed with colourful mosaics, plant communities made of too many species to count in passing. But where their neighbours have discovered resilience in staying small and scrubby, hunched against the bleak climate, the cider gums tower above other life forms, growing up to 20m in height. In the right conditions, these slow-growing trees should comfortably live to 100 years, although recent research has suggested that they might actually live to five times that age.

I’ve heard this species referred to as the Weeping Trees. One reason for the name is rather obvious. During the warmer months, the trees weep a sugary sap, and when the sap hits the yeasts in the air, or pools at the base of the tree, it begins to naturally ferment. This microbial event results in a lightly alcoholic sap that tastes like cider and smells like a brewery. You can catch that scent from quite a distance. It has a significant pulling effect.

The other reason they may be called the Weeping Trees is their affective impact. When I meet my first cider gum, I find I’m completely overawed by it, even close to tears. Apparently, this is a common response. The tree is magnificent. From under its tangled boughs, I can understand the old cliche: that standing beneath the canopy of a tree can feel like standing in a cathedral. The limbs diverge wildly, the timber creases and folds like flesh. The bark is spellbinding, distinctively stained in warm streaks suggestive of honeycomb, black coffee, or a river steeped in tannin. This is a tree that demands reverence.

The Miena cider gums might appear indomitable, but in truth, these trees are facing an uphill battle. Among the living trees dead and dying specimens abound, their forms resembling the bleached skeletons of beached whales. Even the dead trees are breathtaking. There are only eight small stands currently known, occupying in total just a few hundred hectares, and their numbers are in decline. The stands are remote from one another and so genetically diverse fertilisation is increasingly unlikely, leading to a gradual decline in plant fitness.

Threats are numerous and persistent. Introduced deer move about the landscape in large herds. Bucks rub their antlers against the trunks of trees to remove the velvet they have grown over summer. For a young tree, this rubbing can be fatal, preventing the movement of water from roots to leaves. Although invasive species cause significant damage, the chief culprit in the decimation of these trees is climate change, generating a complex ricochet of challenges. It threatens the frosty conditions the trees rely on, increases the numbers of voracious boring insects, and heightens the probability of drought and fire. In 2019 large numbers were lost in the Great Pine Tier blaze that ripped through the area – a huge blow for the species’ conservation. Last, without active management, possum browsing is an escalating concern. For a possum, the leaves of the Miena cider gum are exceptional and their bottomless appetites can quickly strip a tree. Convincing them to go easy on these trees is one of the biggest challenges faced by conservationists.

Eve Lazarus, conservation program manager for the Derwent Catchment Project, takes us to the healthiest stand of protected cider gums. The fencing is intense. It takes some effort to simply open the gate. Inside, about 20 mature, leafy trees are standing tall and steady. Innumerable saplings are dotted about, many ringed with wallaby wire. Fences inside fences suggest a precious assembly. That these trees are widely valued for their ecological and cultural significance can be seen in the active land management practised, not only by First Nations leaders and conservationists, but by landholders and businesses across the region that also play a crucial role in the survival of this species. The cider gums, it would appear, have an energising effect. Here, they have brought together otherwise unconnected groups, working together to reinstate balance to a distressed environment. The connection these people feel towards the trees is evidently a potent one.

Eve discovers one of the trees is weeping. I have a quick taste of the sap and instantly understand what all the fuss is about. The stuff is moreish. I notice every tree boasts a handful of hollows that offer shelter for many different types of life. Striated pardalotes dart about in the branches, peeping loudly, asking us to scram. In terms of the local ecology, the gums are essential. But threat is evident all around. Outside the fence, I see deer hoofprints spread out like a rash. The fence has been breached in spots and wombat burrows have appeared. There is some marsupial scat. As we’re leaving, I come face to face with a chunky possum. It has broken into the enclosure via the wombat holes, and looks well fed. We stare at each other, the possum and I, before it turns and ducks into a cider gum hollow. Eve is relatively unfazed; she even seems entertained by the marsupial’s audacity. After years on the project, she’s accustomed to setbacks. The enclosures will need wombat gates. More funding is needed. But I feel a weight in my chest. The possum has rattled me. I already feel attached to these trees, and I can’t help but take the intrusion to heart.

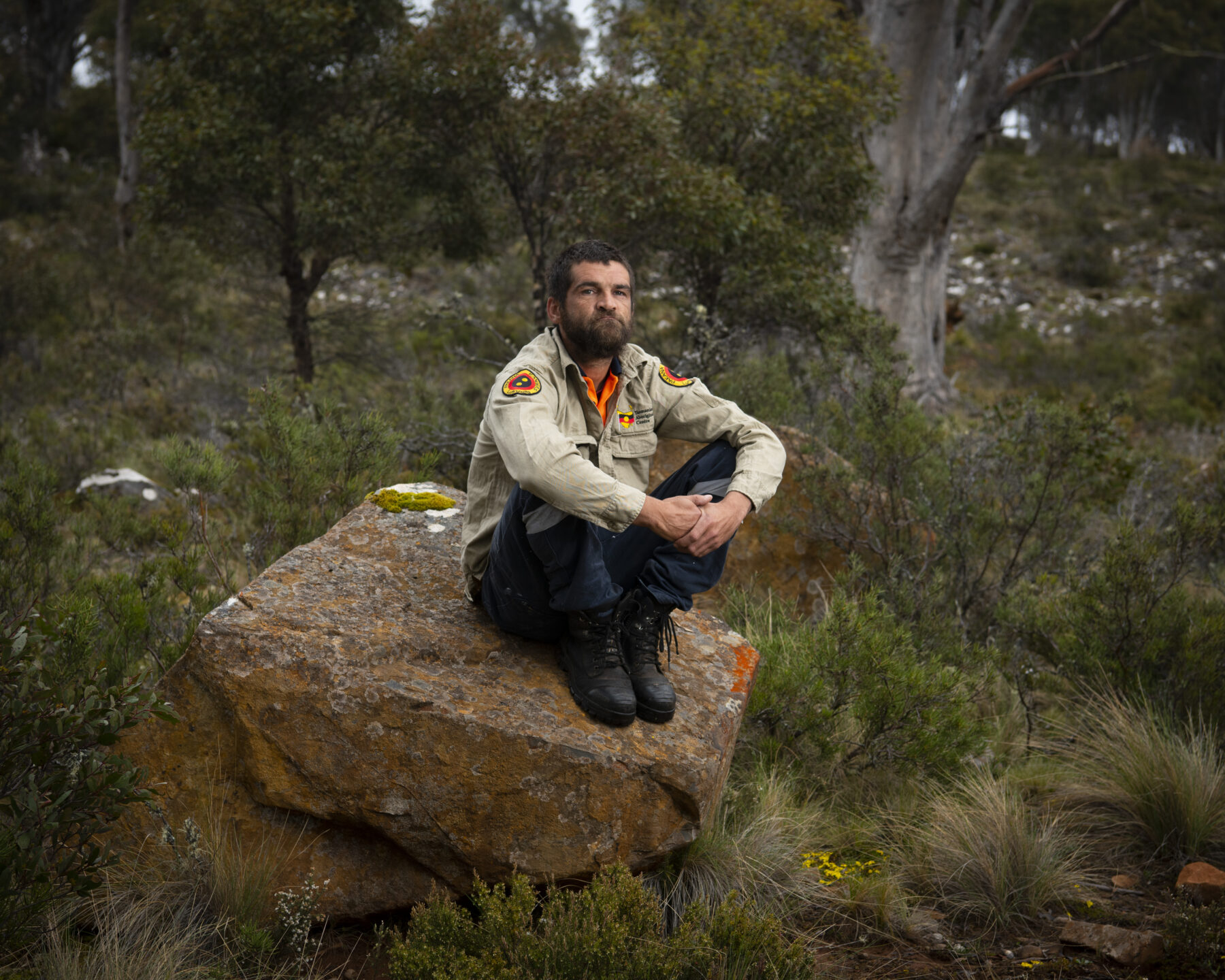

It’s often the case that the value of a species is not considered until its numbers are in decline, but when it comes to the Miena cider gum, the cultural and ecological value of these trees has been recognised by the palawa (Tasmanian First Nations people) for millennia. Some trees even bear the marks of ancestors having tapped into the trunk. It stands to reason then that palawa care will lead the charge in protecting these trees. pakana/trawlwoolway man Andry Sculthorpe is the land and heritage coordinator for the Tasmanian Aboriginal Centre (TAC) and leads the ranger program. “They’re like wise old Elders, so they carry a lot of respect,” Andry says of the trees. At trawtha makuminya, a property owned by the TAC, it’s understood that the value of the Miena cider gum sits entirely outside the dollar, and the current vulnerability of the trees indicates a broader sickness, namely a colonial value system that ignores the innate worth of the natural world and continues to assess it primarily in terms of its economic value – either as a resource to be extracted or as an encumbrance to be eradicated. The harm caused by this mindset is directly evident in the health of the cider gums. “They’re calling out to us in some way; it’s an alarm going off when we see these trees,” Andry says.

Through cultural practice and the passing down of inherited knowledge, it’s a call the rangers are heeding. That the Miena cider gums at trawtha makuminya are beginning to bounce back under the care of pakana rangers indicates vital ecological improvement and reaffirms the need for land-return initiatives and a decolonising approach. In lutruwita, these initiatives have proven not only to repair the disconnect enforced under colonial rule, they also help restore the living systems that existed before colonisation. Andry points out that a colonial value system is not only detrimental to the natural environment, but also to humans. Only in care for Country is human wellbeing ensured. “Even if we’re not aware of it, that actually underpins our existence.”

Efforts to conserve the Miena cider gums prove that assigning value to a species is not useful without acknowledging the larger system within which they exist. The pakana approach acknowledges this essential entanglement. Placing traditional knowledges and value systems at the heart of conservation appears increasingly necessary. For the Miena cider gums, and for the multi-species community with which they connect, such an approach will undoubtedly prove invaluable.