It was the early 2000s, and Trevor Barry had just enrolled in a graduate certificate of science in astronomy at Swinburne University of Technology. The fact he hadn’t completed high school, let alone a university degree, proved only a minor impediment to enrolment for the already accomplished amateur astronomer.

The only caveat the university imposed was that he had to achieve at least credits in all subjects. No problem. “I’m an enthusiastic person,” Trevor explains. It’s an understatement that’s clearly evident after only an hour’s conversation with the lifelong resident of Broken Hill.

That trademark enthusiasm did waver slightly, however, at the beginning of the course, when he had to introduce himself to his fellow students from around the world. “There was a guy in the USA and he commissioned nuclear submarines for the US Navy, and there was a guy in the UK who was an ex-British Airways captain; he’d flown the Concorde,” Trevor recalls. “And I said, ‘Well, I’m Trev, and I’m an ex-miner from Broken Hill.’”

Trevor frequently describes himself as such. It’s as if he’s reminding himself that, even though he receives international astronomy accolades and personal invitations to visit NASA, has had multiple co-authorships of papers in the most prestigious scientific journals, and is on a first-name basis with some of Australia’s – and the world’s – leading astronomers, he’s still also Trevor Barry, a fitter/machinist from the mines of outback New South Wales.

From mineworker to stargazer

Traditionally, a story like this would tell of a child captivated by the stars from an early age, and for whom fate had other ideas. But that’s not how Trevor tells it.

“I wasn’t interested in astronomy at all,” he says. “Most of the population doesn’t look up.” The child of a mining father – a former Rat of Tobruk – and a housewife mother grew up in Broken Hill, but left high school after four years to become an apprentice machinist in a zinc mine, because “that’s what young people in Broken Hill did”.

For the next 34 years, he worked in the mines, making good use of the diversity of skills he’d learnt as an apprentice on rotation around the mine’s power station, engineering design office, and maintenance departments on the surface, underground and in the mills. The career taught him to be resourceful.

“Often when something broke down, we wouldn’t have the specific necessary spare parts, but that machine had to work,” Trevor says. “There’s always a solution to just about any problem, but you have to think outside the square.”

One day, an apprentice in Trevor’s department asked him to take a look at a telescope he’d built from scratch. Trevor took some persuading – “why would I want to look at or through a telescope?” – but eventually, one cold winter night, he made his way to the apprentice’s house. The 1.5m long, 8″/203mm-aperture Newtonian telescope, set on a German equatorial mount, was on the back lawn.

“He pointed out this nondescript star-like point of light, and said, ‘That’s what we’re going to look at’,” Trevor recalls. He looked through the telescope, and saw Saturn, its ring system and atmospheric banding, in full splendour. It was love at first sight, both with the planet and the idea that a homemade telescope could bring this celestial wonder into sharp focus. “I had to do something about that,” Trevor says.

Armed with a book from Broken Hill City Library on how to build Newtonian telescopes, Trevor constructed a 10″/254mm-aperture telescope, with an equatorial mount – complete with counterweights – anchored to three concrete-filled holes in the back lawn carefully maintained by his wife, Cheryl (“I got in a bother with the missus over that,” he admits).

A pair of lawnmower wheels enabled him to move and store the mount under the back veranda, while the telescope itself was deposited in a spare bedroom. That was all fine until one day, while extracting the mount from under the verandah, Trevor lifted one of the mount’s legs too high and, in accordance with the laws of physics, the counterweights did the rest. “Pulled me straight over the top and landed me in the ‘gorgeous-and -adorable’s’ rose garden,” he says.

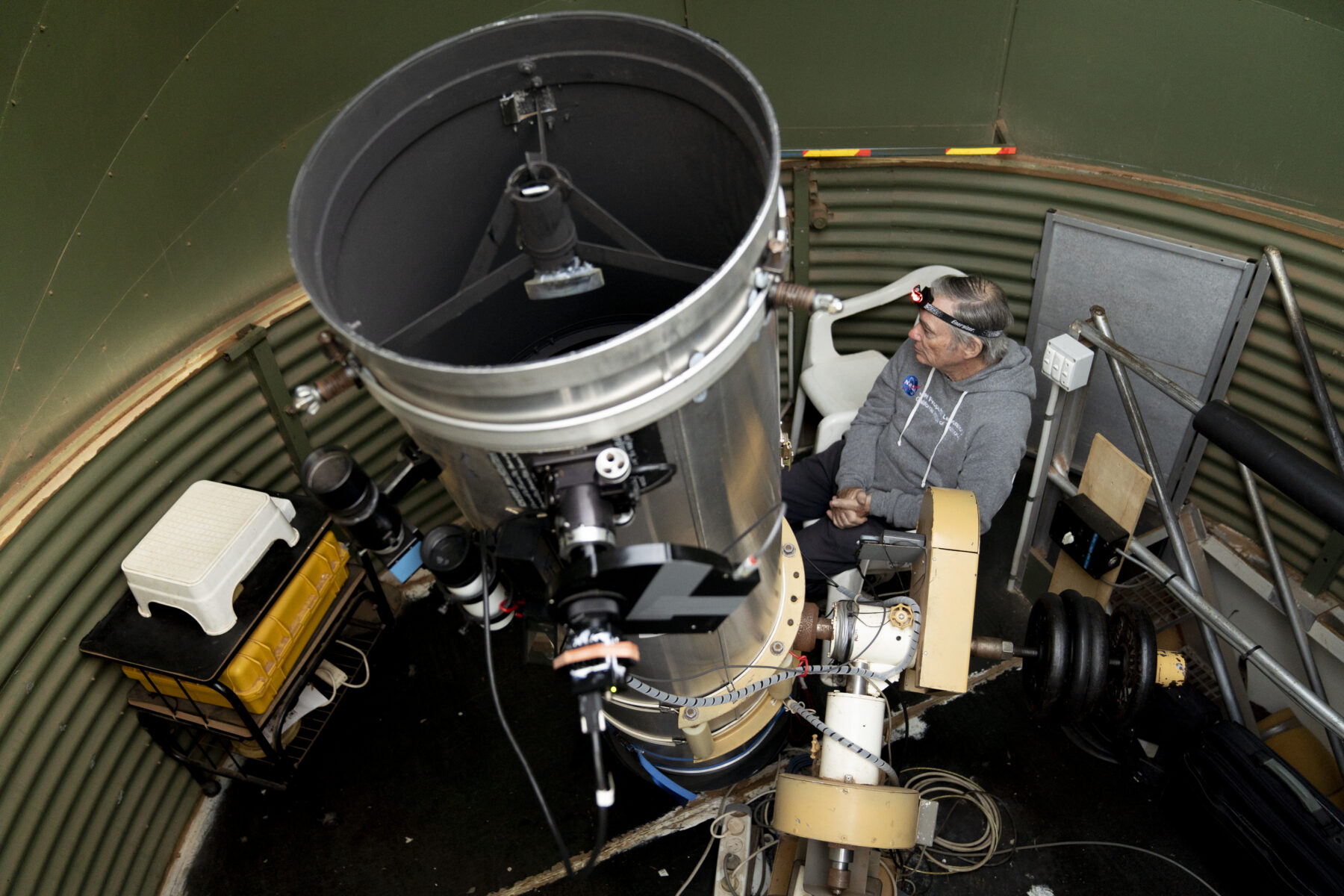

With nothing seriously wounded except his pride, he set about building a permanent observatory and bigger telescope made from – among other items – a water tank, washing machine parts and a wire from Trevor’s catamaran.

Taking on university study

When economics and a back injury brought his career in the mines to a close, Trevor was finally able to focus entirely on astronomy. He signed up for the Swinburne course, with encouragement from luminaries Fred Watson, AG’s longtime space writer, and British/Australian astronomer David Malin, who’d visited Trevor’s outback observatory a year or so earlier.

Much to Trevor’s own surprise, he not only graduated from the course with straight high distinctions, but was awarded the prize for top student in the year. He’d loved the study, absorbing every bit of information “like a sponge”. So when a strange white spot appeared travelling across the vast swirling face of Saturn, Trevor recognised it from one of his textbooks as a rare electrical storm.

At the time, NASA’s Cassini probe was orbiting Saturn, sharing the wonders of the ringed planet and its family of icy moons. However the probe had only limited ability to photograph and track the storm.

With help from Watson and Malin, Trevor managed to get his telescope image in front of Georg Fischer, part of the radio- and plasma-wave science team with the Cassini mission…and thereby launched his second career as an astronomer.

Joining a worldwide network

Trevor is now an integral part of a global network of amateur-run observatories that regularly supply visual information to the world’s space agencies to help guide their missions and observations.

His personal beat is Saturn, which was particularly handy for the Cassini team. “Whenever his [Georg Fischer’s] RPWS instrument detected [what] he called SEDs – Saturn Electrostatic Discharges – he’d contact our team, sending an email with the challenge to hunt down the optical counterpart to his radio source,” Trevor says.

Since the planned demise of the Cassini probe in September 2017 – an event Trevor also managed to capture with his telescope – the outback starman has continued his observations of the ringed gas giant, working with astrophysicist Agustín Sánchez-Lavega, who heads up the planetary science and applied physics groups at at the University of the Basque Country

in Spain.

“Whenever I think I’ve found something new, I fire right up and I harass the crap out of Agustín,” Trevor says. Agustín is the settling influence to Trevor’s excitable enthusiasm, right up until Trevor discovers something new, “then look out when you’ve got an excited Spanish astronomer”.

One of four scientific papers that Trevor has co-authored with Agustín describes an enduring storm in Saturn’s incredibly turbulent equatorial zone (see nature.com/articles/ncomms13262), which Trevor first imaged as an odd white spot and brought to Agustín’s attention. It was so unusual that both the Calar Alto Observatory in Spain and the Hubble Space Telescope were used to take a closer look. The findings resulted in one of Trevor and Agustin’s co-authored Nature papers, coincidentally published on Trevor’s birthday.

Another project used Trevor’s 3115 Earth-days-long study of Saturn’s ‘hexagon’ – the spinning six-sided jet-stream phenomenon around the planet’s north pole – and suggested the rotation rate of the hexagon might be connected to Saturn’s interior rotation.

Trevor’s extraordinary contributions were recognised in 2022 with the Astronomical Society of Australia’s Berenice and Arthur Page Medal for excellence in amateur astronomy), for which he was a joint award winner, then internationally in 2023 with the Walter H. Haas Observer’s Award from the Association of Lunar and Planetary Observers. “How was that?” Trevor exclaims. “A mineworker from Broken Hill!”

Despite being in his 70s, Trevor shows no signs of slowing down in his new career. He’s feeding images of Jupiter to NASA’s Juno mission, helping the team to decide at where to point the spacecraft’s imaging equipment each time it does a flyby of the planet. He has also directed his telescopes at Mars and Venus.

When not tending to the grounds at his local lawn bowls club – Trevor is also an award-winning lawn bowler – he’s revisiting his fitter/machinist roots, and tweaking his telescopic set-up to improve its function and capture regime. “I’ve always been a tinkerer, but I took that to another level with astronomy,” he says. “I do nothing in half-measures.”