No one has ever seen a live spade-toothed whale. And until two weeks ago, no one had even seen a whole body of the creature.

That was when an intact carcass of a male of the species was found on a beach in Otago, New Zealand.

It was discovered by beachgoers who notified New Zealand’s Department of Conservation (DOC), which didn’t realise the significance of the discovery until its staff arrived and saw the 5m-long beaked whale.

After closer inspection and consultation with marine mammal experts the team soon concluded the carcass was that of the extremely rare species.

To appreciate the magnitude of this find, let’s rewind the clock back to the early 1870s. At this time, no one knew the whale existed.

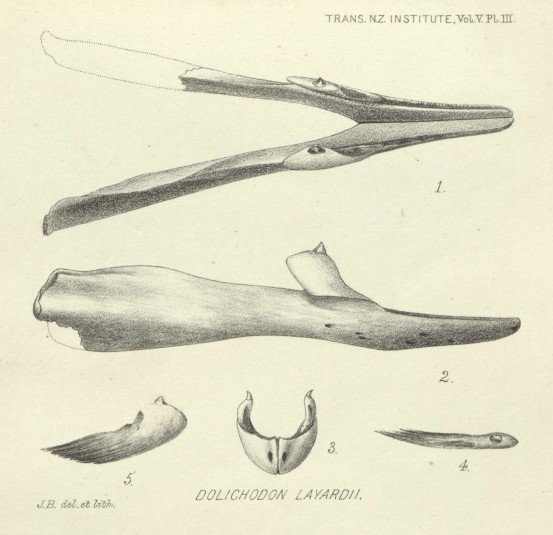

Then, in 1872, an unusual lower jawbone and two tusk teeth were collected from New Zealand’s Pitt Island by naturalist Henry Travers, explains DOC marine mammal expert Anton van Helden.

Two years later, Scottish geologist James Hector used these skeletal remains to describe the species as a strap-toothed whale (Mesoplodon layardii). But in 1874 British zoologist John Gray studied Hector’s description and “decided that it should be a new species and gave it the species name traversii, after Henry Travers,” says Anton.

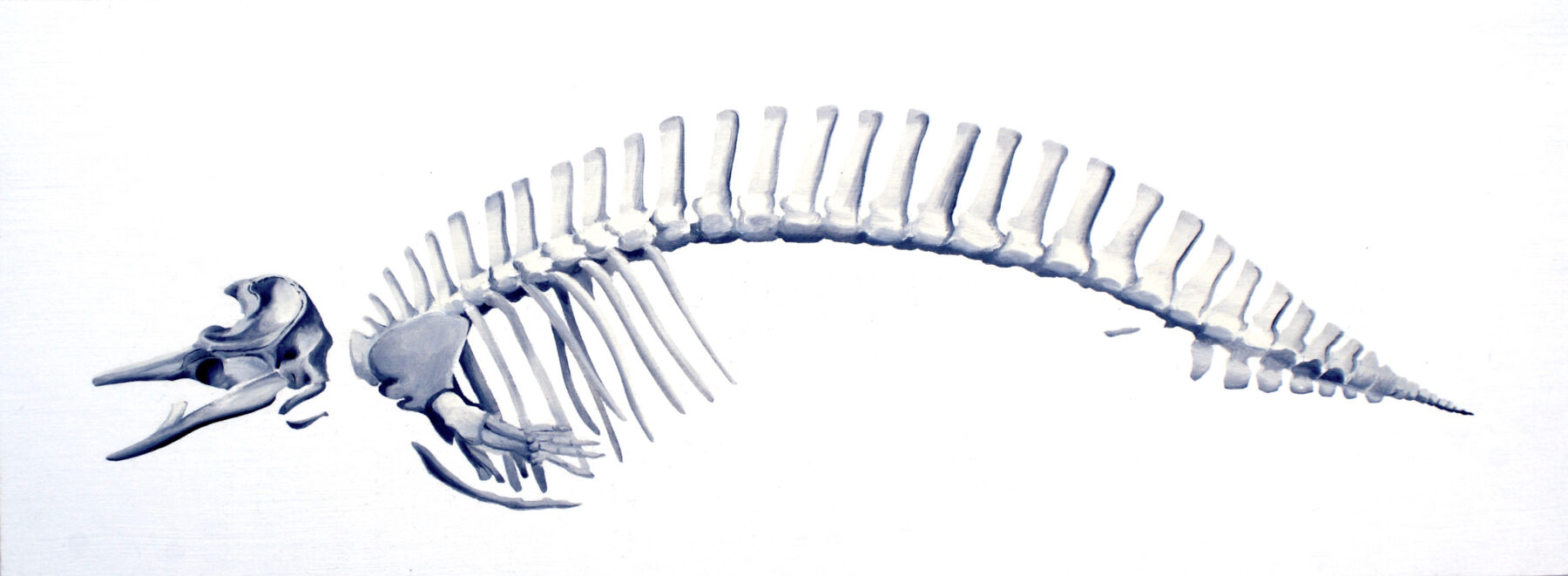

It wasn’t until 1950 that any evidence of the species surfaced again, when a partial skull was found, again in New Zealand, on White Island. Decades passed until, in 1986, another partial skull was discovered, this time on Chile’s Robinson Crusoe Island. In 2002 a scientific paper was published, confirming “based on comparing the morphology of the skulls, and the DNA of all three known specimens, that they were all the same species,” Anton says.

Still, no one had seen any more of the animal than a few skeletal remains, so nobody knew what it looked like and it might have already gone extinct.

In 2010 not one but two of the animals were finally seen in the flesh – albeit dead with parts missing by the time they were found – when a mother and calf stranded in New Zealand’s Bay of Plenty.

At the time, however, the find was considered unremarkable. Whale strandings are common in New Zealand and it was assumed the whales were Gray’s beaked whales (Mesoplodon grayi), the most common strandees.

As per national protocol, however, photographs, body measurements and tissue samples were taken before the carcasses were buried on the beach where they were found. DNA sequencing soon matched the mother and calf to the existing samples of spade-toothed whale skeleton in the database.

Finally, the spade-toothed whale’s physical appearance could begin to be documented.

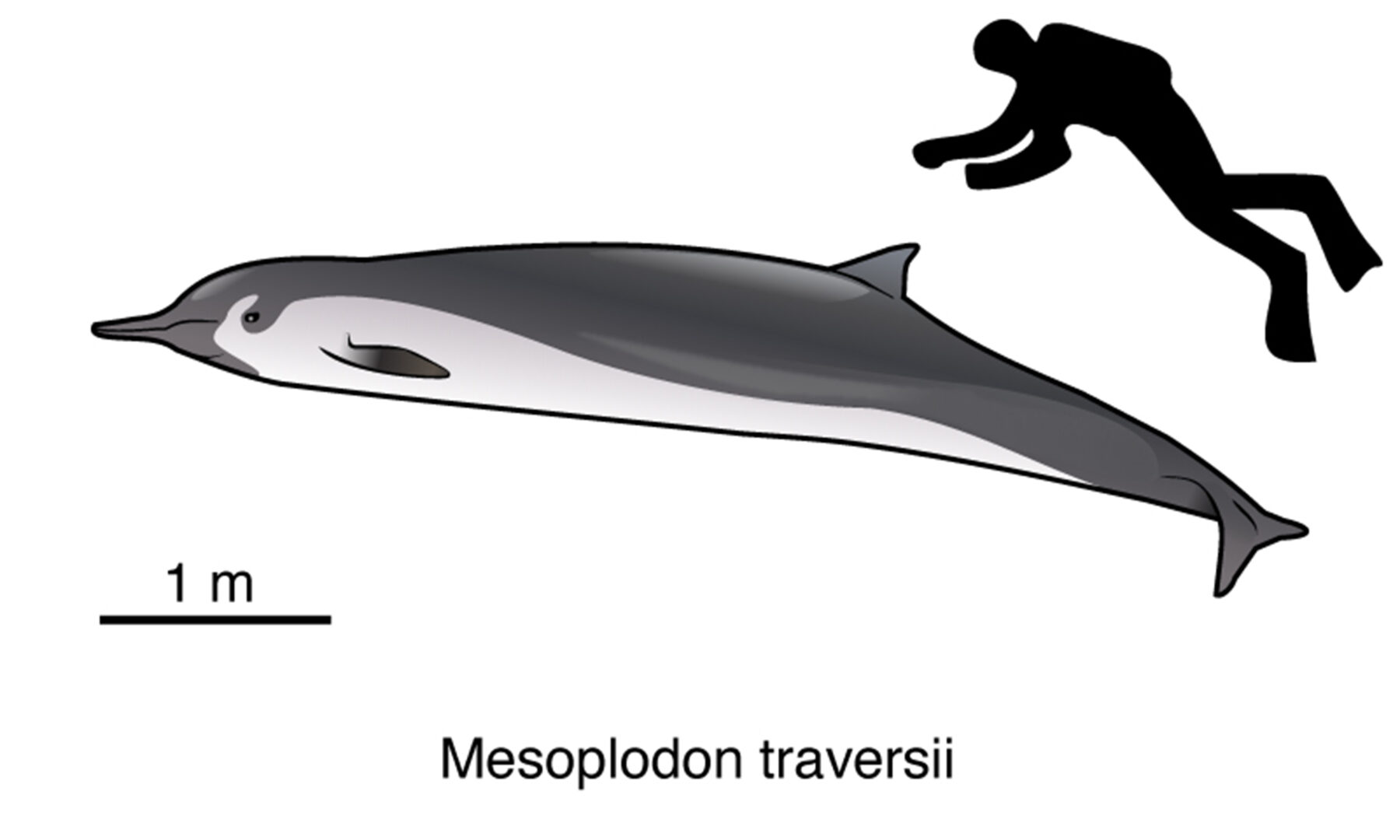

“This was the first time the species had been seen with flesh on,” says Anton, “and from which the first tentative description of the colour pattern and external morphology was done.”

After the DNA revealed the significance of the two whale bodies they were exhumed from the sand and are now preserved at Te Papa Tongarewa (Museum of New Zealand).

In 2017 another partial body washed ashore, in New Zealand’s Gisborne. Again, it was at first mistaken for a Gray’s beaked whale, identified later as a spade-toothed whale using photographs.

Anton says this specimen – also now in Te Papa Tongarewa’s collection – gave scientists the “first really good idea of what the colour pattern of the animal was and other key external features.”

Fast forward to two weeks ago – July 4 – when the latest spade-toothed whale was found – only the sixth recorded specimen, the third including body tissue, and the first fully intact.

DOC Coastal Otago operations manager Gabe Davies summarises the magnitude of the find: “Spade-toothed whales are one of the most poorly known large mammalian species of modern times. Since the 1800s, only six samples have ever been documented worldwide, and all but one of these was from New Zealand.”

What do we know about spade-toothed whales?

Everything science currently knows about the spade-toothed whale (Mesoplodon traversii) comes from two partial skulls, a jawbone, a few teeth, and three specimens washed up dead on beaches.

It’s one of 21 species of beaked whale (family Ziphiidae) and there are only subtle differences – in size, teeth, beaks, and colour – between them all.

It’s thought they spend most of their time at extreme ocean depths, explaining why they are so rarely seen by humans. Another possible reason why they are scantily seen is that there are simply so few of them.

New Zealand seems to be a hotspot for the family with 13 species of beaked whales recorded in waters surrounding the island nation.

Spade-toothed whales are classified as ‘data deficient’ in the New Zealand Threat Classification System.

Image credit: Jörg Mazur via Wikimedia Commons

Next steps

Genetic samples already taken from the body will be processed by the team at University of Auckland’s New Zealand Cetacean Tissue Archive. This DNA will provide official confirmation that the species is indeed a spade-toothed whale.

The whale’s body has since been removed from the beach where it was found and is being preserved in cold storage while the next steps are discussed.

A body this fresh offers the first opportunity in history for a spade-toothed whale specimen to be dissected.

“From a scientific and conservation point of view, this is huge,” Gabe says.

But there are many stakeholders to consider.

DOC is working in partnership with Te Rūnanga ō Ōtākou (the organisation representing the local Mauri peoples of the land on which the whale was found) to make decisions involving the whale’s remains.

“It is important to ensure appropriate respect for this taoka [sacred/treasured animal] is shown through the shared journey of learning, applying mātauraka Māori [Maori knowledge] as we discover more about this rare species,” says Te Rūnanga ō Ōtakou chair, Nadia Wesley-Smith.