In Australia’s mangrove-lined mudflats and estuaries live armour-plated mud-dwellers with massive bone-crunching claws.

Emerging from muddy holes and hides with the ebb and flow of the tides, the giant mud crab (Scylla serrata) – also known as the green mud crab – forages for molluscs, other crabs and carrion. Despite its huge claws – which it wields in front of itself like medieval shears – its flesh-filled carapace (outer shell) makes it the prized quarry of crocodiles, turtles, fish and hungry humans.

But despite the ubiquity of the giant mud crab on the coast of tropical and sub-tropical Australia, there’s still a lot we don’t know about its lifecycle.

Once thought to be a fairly small-ranging inshore inhabitant, recent tracking studies have found egg-bearing females venturing 100km or more from their estuaries, while prawn trawlers have hauled them up in nets more than 50km offshore.

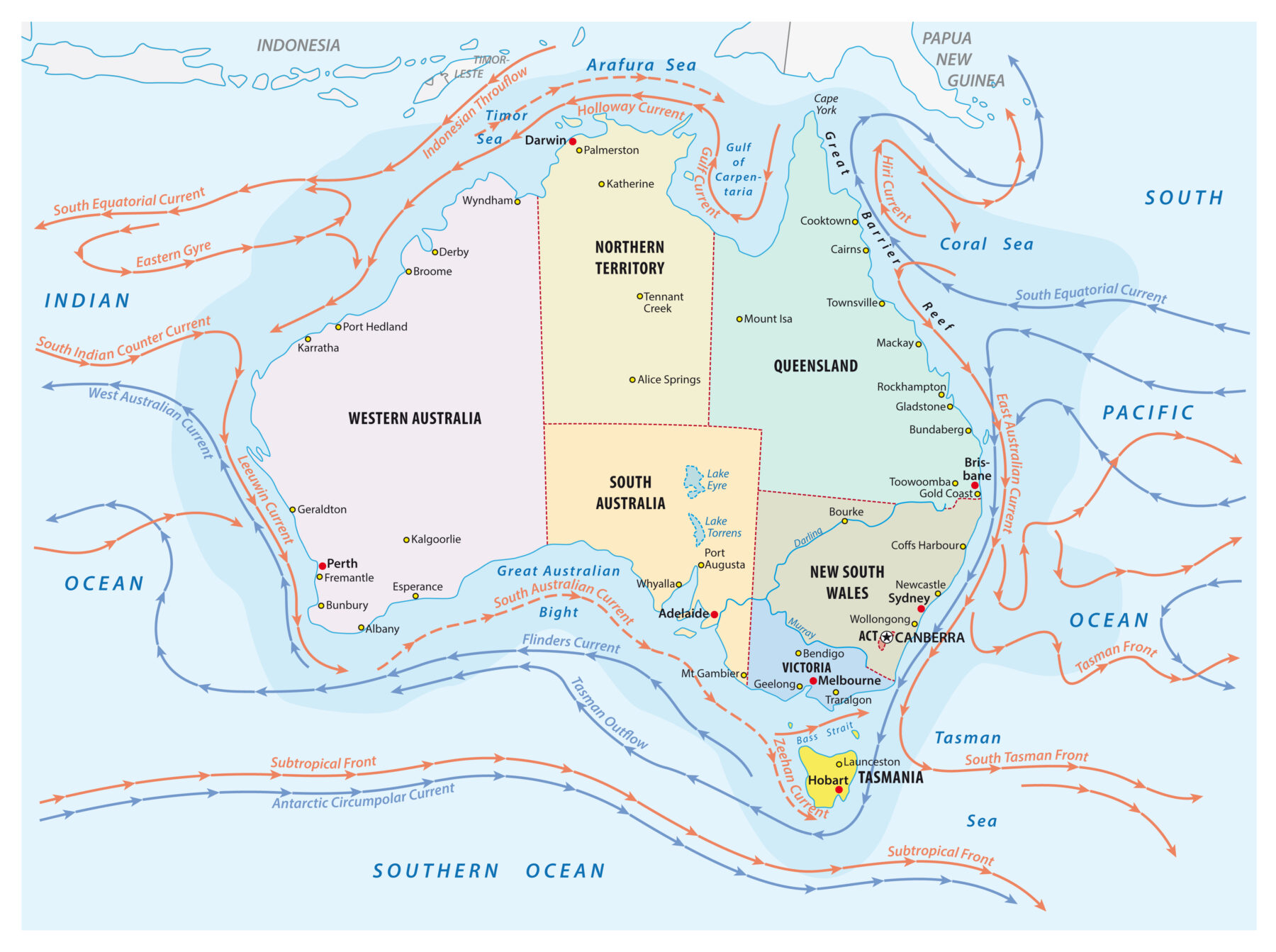

Now scientists suspect that, on the east coast at least, some large pregnant females end their lives with an exhausting one-way trip to rendezvous with the East Australia Current (EAC).

Up to five million eggs

In Australia, the giant mud crab ranges from around the Exmouth Gulf in Western Australia, across the north of the country, and down into southern New South Wales.

They have a lifespan of 3–4 years, and in warmer northern waters – where they grow fast and remain active year round – they can tip the scales at nearly 3kg and measure almost 30cm across the carapace.

Young crabs – measuring just 8cm across – have a bite force of up to 40kg, enabling them to break open oysters and shellfish and to defend themselves from their cannibalistic cohorts.

Studies show they spend their first couple of years mostly estuary-bound, where they periodically moult their shells, replacing them with larger, soft models that harden over a few days.

It’s during this soft-shell phase that they’re most vulnerable to predators, but also when females are most likely to have their eggs fertilised.

Pregnant females can carry up to five million eggs and after spawning, the larvae will drift for several weeks before settling to the seabed.

A ‘bold move’

Though it’s been known for some time that some egg-bearing females travel offshore to spawn, marine and estuarine ecologist at Queensland’s Griffith University, Olaf Meynecke, wanted to figure out exactly where they go.

“When we are at sea, I’ve often seen mud crabs swimming on the surface and heading [in the direction of] the East Australia Current, which is such a bold move,” Dr Meynecke says.

“One of the theories we had was that it was the mature, older ones that leave the estuaries and release their eggs offshore and then die [out] there.”

From a biological perspective, he says if that is what’s happening, then it’s an intriguing strategy – older females using the last of their energy and resources to trek to the EAC to spawn millions of fertilised eggs, with the immense current spreading their genes far and wide as they take their final breath.

Uncooperative crabs

In the hope of getting some hard data to prove this theory, Dr Meynecke fitted acoustic-tracking devices to female giant mud crabs in estuary systems in south-eastern Queensland. Some crabs were also fitted with depth sensors.

But the crabs didn’t play along – most stayed in the rivers or headed out into the bay, but ventured no further. Two were unable to be detected after being tagged.

Though they got some interesting data, such as the correlation between the crabs’ movements up and down the river systems with tidal flows, it was also a costly exercise that got them no closer to confirming the theory.

“It was pretty expensive. One of those tags costs $500–$600,” Dr Meynecke says. “But that’s the nature of that kind of work.”

Dr Meynecke published numerous papers on mud crabs, but didn’t do any further acoustic tracking studies and has since moved on to other research interests.

Tagged female detected around 150km from home

Since Dr Meynecke’s research, more scientists have been tagging giant mud crabs with the same questions in mind: Where do they go when they leave the estuaries, and why?

Dan Hewitt is a post-doctoral fellow in Sydney’s UNSW Coastal and Regional Oceanography Lab.

He got support from the Fisheries Research and Development Corporation (FRDC) on behalf of the Australian government, and co-funding from the NSW Recreational Fishing Saltwater Trust, to fit acoustic tags to almost 90 mature female giant mud crabs over a two-year period in the Clarence and Kalang Rivers in New South Wales.

He found the crabs were most likely to start their spawning migration on larger tides of the full and new moons, and after heavy rainfall.

Fourteen of his tagged crabs left the estuary and all made a dog-leg and headed north, pinging radio receivers as they went.

“Some only [travelled] about 20km,” Dr Hewitt says.

But one crab travelled 69km from its home estuary, and Dr Hewitt says he’s had others go even further.

“We’ve had a female, not included in that paper, that was detected something like 150km from the estuary where it was tagged.”

He published his findings in Estuaries and Coasts – the journal of the Coastal and Estuarine Research Federation – in 2022.

Findings add weight to EAC theory

The question remains: How far offshore are they headed? And is this really a fait accompli for the mud crab, driven by a Darwinian imperative to spread its genes?

The radio receivers, which were situated along the coastline, got pings from the tracking tags attached to the crabs when they passed them. So, while the receivers are good for telling us how far north the crabs travelled, in this study they can’t say how far offshore the crabs were.

But Dr Hewitt thinks the fact that all the crabs headed north adds weight to the EAC hypothesis. He says it’s a strategy that a bunch of species, like tailor and prawns, exhibit in New South Wales.

“They live in this region where the EAC flows predominantly from the north to south.”

Hypothetically, were generations of crabs to spawn due east into a south-flowing current, there’d end up being a southerly genetic drift that would eventually take them beyond suitable habitat.

A modelling paper – also published by Dr Hewitt and colleagues – found that mud crab larvae typically come from the north, and that there is a high degree of connectivity between Queensland and NSW populations.

He thinks they probably only head out as far as they need to in order to take advantage of the current, and what that distance is likely varies a lot by location.

Research in preprint this year, which is yet to be peer-reviewed, modelled where mud crab larvae would end up based on how far from shore it was released at different locations along the Queensland coastline.

Not surprisingly, the study found an overall trend that the further from the coast the larvae was released, the further it was likely to spread before settling.

Exceptions

Of course, there were exceptions.

In some locations, such as Princess Charlotte Bay in far north Queensland, local currents and eddies meant it was hypothetically possible for crabs to spawn several hundred kilometres offshore, only for the larvae to settle right back on the coast where the mother had departed.

On the other hand, larvae spawned in the Hinchinbrook Channel – located between the mainland and Hinchinbrook Island in the Whitsundays – could be carried both north and south, due to a split in the near-shore current there.

What we know for sure

More research will be needed before it can be determined exactly how far offshore the crabs are travelling, and that data will almost certainly be location-specific.

But one thing Dr Meynecke and Dr Hewitt are both convinced of is that it’s a journey of no return for the females.

“I think by the time they do all that and then finally spawn, they’re probably pretty depleted,” Dr Hewitt says.

“When they’re so low in energy, I think they probably get picked off by a shark or a seal, or [other predator].”