DNA tests reveal orcas killed great white for only its liver

When the mauled body of a 4.7m-long great white shark washed up on a beach near Portland in western Victoria in 2023, the question on everyone’s lips was what could have inflicted these fatal wounds, which included a massive bite – 50cm in diameter – near the shark’s pectoral fin.

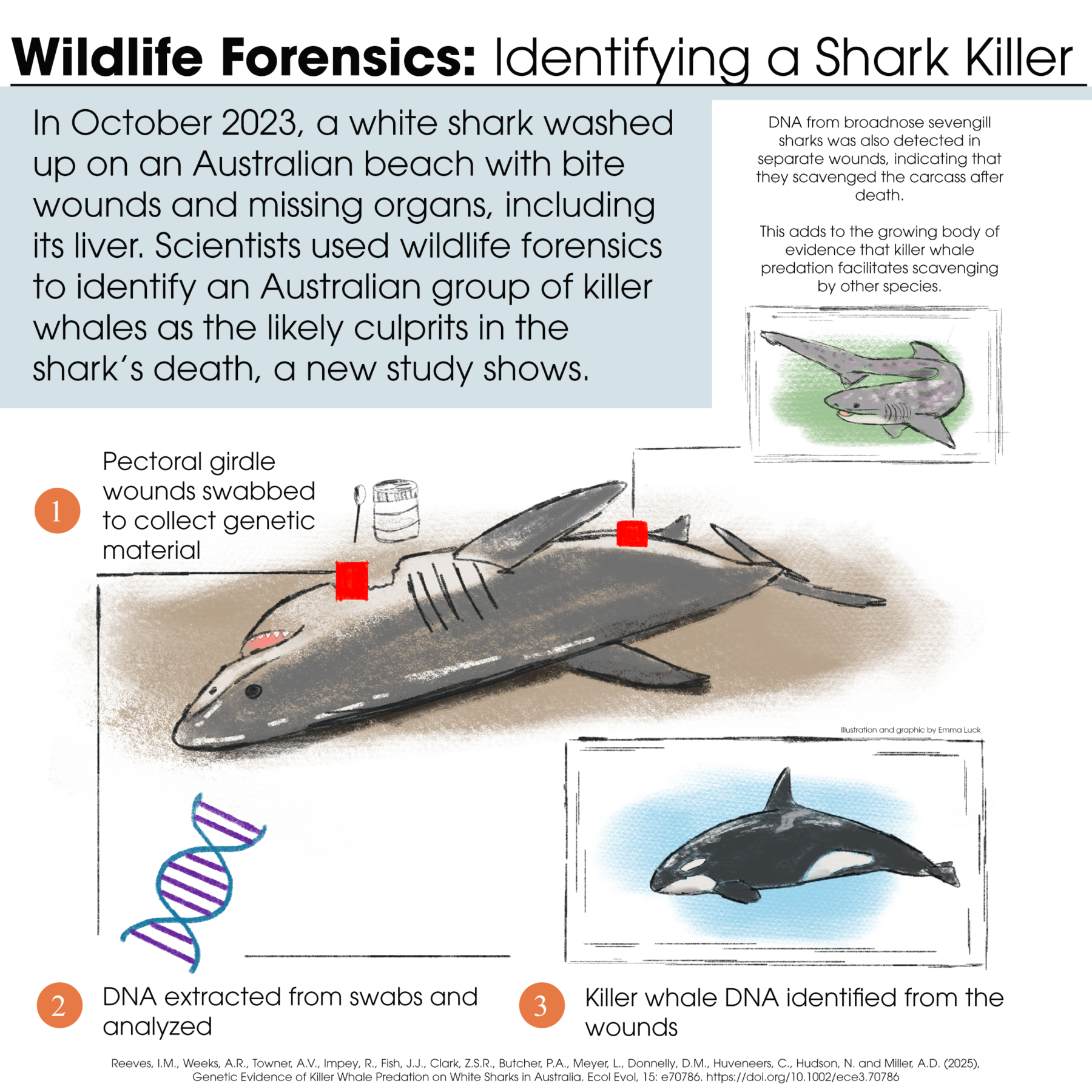

At the time, it was suspected orcas were behind the shark’s death, so researchers swiftly collected DNA swabs from the shark’s bite wounds to find out for sure. Now, they say their genetic testing has proven that suspicion was justified.

One of the world’s most powerful predators, the orca (Orcinus orca), also known as a killer whale, is in fact the largest member of the dolphin family.

While orca predation on sharks, including great white sharks (Carcharodon carcharias), has been observed in Australian waters before – most notably a suspected kill in 2015 off the coast of South Australia – the Flinders University research team’s findings, published in the journal Ecology and Evolution, confirm this for the first time. It also correlates with confirmed cases overseas.

Targeting the liver

The findings expand on marine researchers’ understanding of orca hunting behaviour and dietary preferences, showing orcas killed the great white for only one body part: the liver.

“The liver, digestive and reproductive organs were missing and there were four distinctive bite wounds, one of which was characteristic of liver extraction by killer whale, similar to what has been observed in South Africa,” said lead research author Isabella Reeves, a Flinders University PhD candidate.

“We were able to confirm the presence of killer whale DNA in the primary bite area, while the other three wounds revealed DNA from scavenging broadnose sevengill sharks.

“These findings provide compelling evidence of killer whale predation on white sharks in Australian waters, with a strong indication of selective liver consumption.

“This suggests that such predation events may be more widespread and prevalent across the globe than previously believed.”

But why the liver? Sharks are different to many fish in that they don’t have swim bladders. Instead, they have large, fatty livers that help them stay buoyant.

Shark liver is “a big, fatty, dream meal for other carnivores with high nutritional needs,” explained shark expert Dr Blake Chapman.

Protecting our top predators

Adam Miller, co-lead author and Flinders University associate professor, said more research is needed to understand how orca predation is affecting great white shark numbers.

“We don’t know how frequently these events occur in Australian waters and therefore how significant these findings are. But these types of predation events in South Africa have further impacted on already declining white shark numbers,” Miller said.

“We know that white sharks are key regulators of ecosystem structure and functions, so it’s very important we preserve these top predators. Therefore, it’s important that we keep a tab on these types of interactions in Australian waters where possible.”

Three local orcas the likely killers

Marine scientist David Donnelly leads the Killer Whales Australia citizen science program and is a field research officer at the Dolphin Research Institute based in Victoria. Donnelly contributed to the Flinders University research by supplying citizen scientist eyewitness accounts that helped identify the individual orcas involved in the Portland great white shark attack.

He and his team of citizen scientists believe three individual orcas known as ‘Ripple’, ‘Bent Left’ and ‘Jagged Fin’ were the orcas involved.

“We now have 20 years of data on Ripple,” Donnelly said.

“In 2005 he was first sighted off Eden in New South Wales. We now know he roams around Tasmania as far west as, I think, Robe in South Australia, and right through Victoria.”

Bent Left has been observed for about two years.

“He has been in Tasmania’s east coast, into South Australia and as far north as Jervis Bay. And he was first recorded off Eden in NSW. So there has been a bit of roaming,” Donnelly said.

The incident in Portland is the first time Ripple and Bent Left have been documented hunting together.

“We know that Ripple is currently the only mature male in one family group, and he hasn’t been seen interacting with Bent Left as far as we are aware,” Donnelly said.

“There might be some records that we haven’t uncovered yet, but as far as we’re aware those two haven’t really [prior to this] interacted the way they have off the west coast of Victoria in this particular event.”

Jagged Fin is believed to be a mature female.

“It wasn’t a surprise to find out that she was associating with Bent Left,” Donnelly said. “There are other records of those two being together. She was actually recently seen with Bent Left in Tasmania just a few weeks ago.”

Image credits: Wild Ocean Tasmania; Wild Ocean Tasmania; Allen McCaughly

‘Fascinating’ DNA technology

David added that while it’s not news to the scientific community that shark liver is “on the menu for killer whales”, this research is “more about the methods that were used to confirm this attack and kill”.

“Using that DNA technology was kind of fascinating,” he said.

“We know that they take sharks. We know that is part of their diet. Having that event being witnessed and then proven with DNA technology is the bit that is really interesting. To be able to get that fine-scale detail is really important.

“Each encounter appears to throw up something new, and this event is a good example of that. We got this predation; we got this interaction between two males that typically don’t hang around together. It’s just so fascinating. And at the end of that day that is what keeps you going: asking ‘I wonder what is coming next?’”

Importance of citizen science

The new research shows how citizen science complements other forms of scientific research in shedding new light on the lives of orcas, Donnelly said.

“We are learning with every sighting event. And we are reliant on citizen science to continue building this story around these animals,” he said.

“Citizen science is incredibly useful. Reporting sightings, reporting strandings, reporting events like this killer whale and white shark interaction is really important.

“It’s not just killer whales; it’s everything. Citizen science plays a huge role, especially with the lack of funding available for scientific research.

“Understanding an animal is the first step towards conserving that animal. Understanding the diet, the movement habits of these animals, the prey, entanglement risk, underwater noise – we need to understand how all that plays a role in the ecology of killer whales if we want to understand them and apply conservation measures to protect them.”