It’s a cloudless day as our vehicle heads across a hillside incised with deep furrows. The bare paddock is tinged with grey stubble, remnants of the last cereal crop to grow on this land. A wide sweep of the eye takes in two dozen figures walking each furrow with dangling bags of native shrub and tree seedlings. At 5m intervals, they insert a plant into the soil and move on.

“Thirty years ago, who would have thought the bush was worth putting back?” says Alex Hams, Bush Heritage Australia’s south-west landscape manager, as we drive slowly past each planter. “Conservation was a word not meaningfully used in Australia then. But I feel optimistic we can make changes in our thinking – and this bush.”

Alex is describing Bush Heritage’s role in taking denuded farmland in Western Australia’s south-west corner and adding new pieces to a vast and complex restoration jigsaw.

We’re visiting Ediegarrup, a 1067ha property 430km south-east of Perth, where plovers rising on nippy winds are the only signs of wildlife. Until recently, Ediegarrup was used to grow cereal crops. But under Bush Heritage’s stewardship it will be transformed into a natural paradise, as close as possible to the unmatched floral biodiversity of nearby remnant bushland. An added bonus is that Ediegarrup will sequester an estimated 85,000 tonnes of carbon in the coming years.

“Today is a bit of a celebration,” Alex says. “You’re seeing the last of the seedlings to go in this year, and we also direct seeded when we made the furrows. Hopefully, we come back here in less than 10 years’ time and it’ll be a thriving bushland community.”

In the pause in conversation, I ponder this rare good-news story from the bush. We stop in the paddock. Alex turns off the engine and we climb out of the ute.

“Last year we planted about 65ha near where we’re standing here,” he says. “This year we’ve planted just over 180ha with 61,000 seedlings. And today we’re putting in the last of them, some 2000 plants.”

Alex introduces me to his colleague Barry Heydenrych, a bush regeneration specialist from Greening Australia. Barry plucks a native seedling from the basket slung around his shoulders and hands it to me. In my other hand he places a heavy, tube-shaped instrument called a Pottiputki planter. He shows me how to stab the sharp end of the planter into the soil, press a handle that spreads a metal claw to make

a hole, take a seedling and drop it down the tube and into the hole. Pressing a button causes the planter to close its claw with a metallic clunk.

“It gives a satisfying clunk every time, because it means you’ve just planted a tree or a shrub,” Barry says, admitting he’s ‘addicted’ to the sound. “There’s nothing better than hearing that clunk on a beautiful day, when the soil is moist and a good selection of plants are going in.”

The planting team includes Indigenous ranger Des Eades, his partner Kylie Hobbs, and ranger coordinator Donna O’Brien. They show me plump bags of seed – sheoak nuts, dust-sized paperbark seeds and golden balls of native sandalwood – that were harvested a mere 3km away at their Aboriginal-owned property, which is named Nowanup.

The ranger team is a respected part of the local conservation community, offering plant knowledge and expert harvesting by collectors, most of whom are women.

Donna explains that these seeds were sourced from her property, which was successfully revegetated using local native species. “Nowanup is now 20 years old, and it’s providing the seed for rehabilitation projects like this one,” she says.

“As a young fella, I remember this place was lush bushland,” says Des, a Goreng Noongar man whose father Eugene is a prominent local leader. “I’m 55 this year, so looking at it now, it makes me feel good that I’ve done my little bit for my grandkids – all 20 of them. There’ll be something here

for them to look at in the future.”

I sense that I’m witnessing more than a simple exercise in tree and shrub planting. The Bush Heritage model is an ambitious mix of revived landscapes, carbon capture and a new kind of connectivity between local people. It’s also part of a much bigger program called Gondwana Link, which aims to link up 1000km of natural habitats across the south-west of WA.

“This part of the south-west is famous for biodiversity and endemism, and the diversity of flowering plants is insanely high,” Alex says. “Our operations contribute towards a really grand and ambitious vision, called Gondwana Link, to create a natural corridor that connects the wet forests in WA’s south-west corner to the dry woodlands and mallee that borders the Nullarbor Plain.”

Alex and I survey the Ediegarrup landscape. He points to the horizon. “That far paddock will remain for farming, but we’re working with those neighbours to see if we can access this one on the right,” he says.

I tell Alex I’m using an imaginary box of coloured pencils – mottled green, grey and gold for native bush – to colour in the grey paddock in front and to the side. The far paddock would remain uniform yellow for canola crops. In time, will I be able to colour in most of the picture with a variety of green pencils? “Yes,” he says. “Almost as far as we can see will be converted into bush cover.”

Dodgey Downs

Millions of trees and shrubs in the south-west were bulldozed from the 1960s onward by state government order to make way for farming. With more than 7500 plant species in the south-west, it seemed hopeless to think this ecological damage could ever be repaired. How do you put back so many native species, many of which grow only in this spot on the planet? Yet tree by tree, flower by flower, hectare by hectare, that’s precisely what’s being attempted.

We head back to spend the night at another Bush Heritage property, Red Moort Reserve. In the late twilight, we detour to shine the ute’s spotlights across a wide forest of red-flowered moort (Eucalyptus nutans). It’s one of the largest remaining eucalypt stands of this species, a magnificent native tree type that Alex jokingly claims “can take water out of a brick” – meaning it can grow in heavy clay soils.

Nestled within Red Moort Reserve is Bush Heritage’s south-west field station, a handsome off-the-grid steel building that opened in 2018 and provides sleeping quarters and offices for scientists, volunteers and visitors.

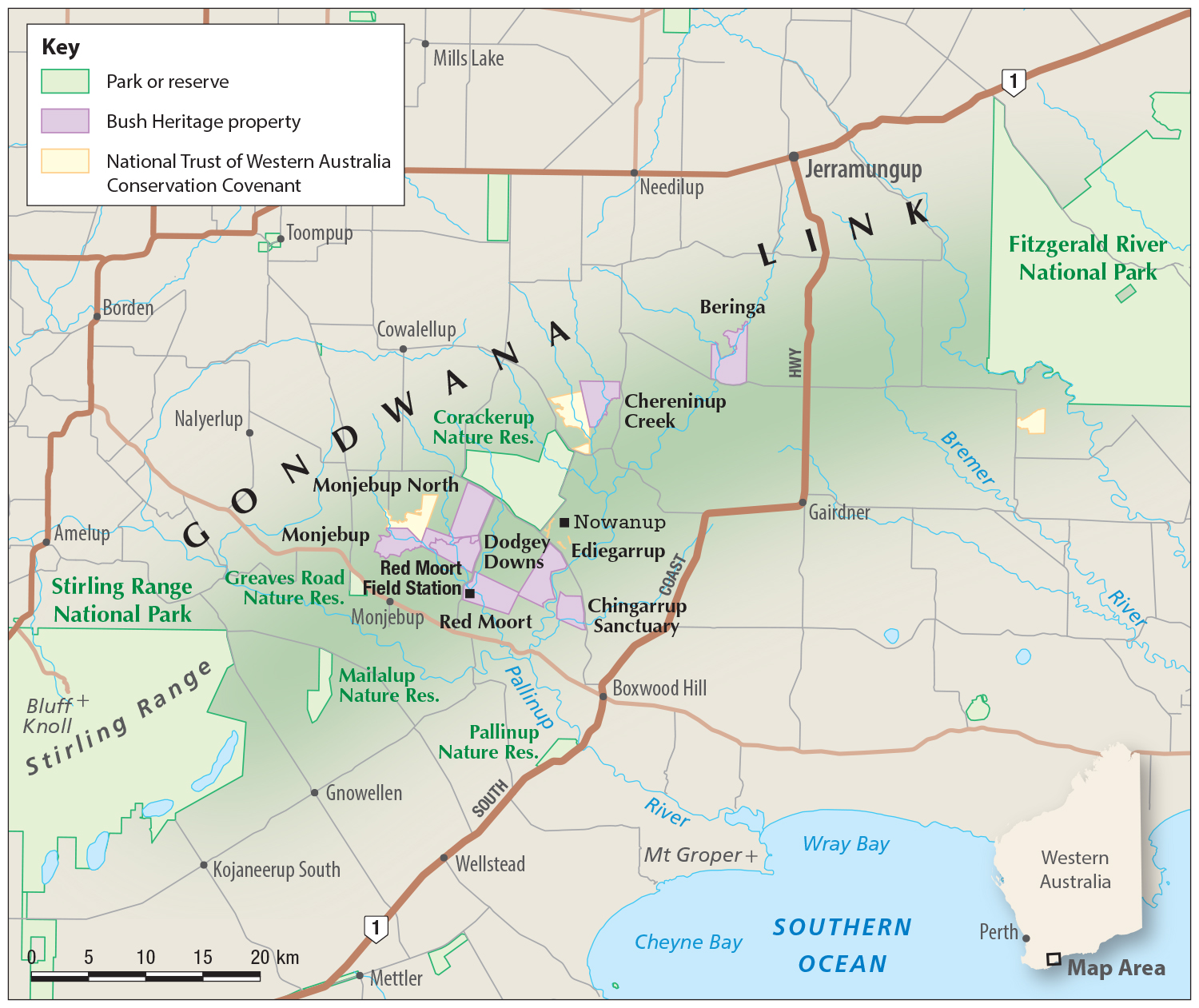

Before dinner, Alex spreads out a map on a table to show me the connectedness of Bush Heritage’s properties in the south-west. He runs his finger along the map, indicating the 200m boundary connecting Red Moort to Ediegarrup. The two reserves loosely connect with other properties – Monjebup, Beringa and Chereninup Creek – and lie close to two nature reserves and the privately owned Chingarrup Sanctuary.

Alex points to two dense green outlines marking the most biodiverse parks in the state: Fitzgerald River and Stirling Range national parks. “We aim to create a mosaic of natural sanctuaries between them,” he says.

Alex says Bush Heritage has recently acquired another property, with the dubious name of Dodgey Downs. I ask him what’s dodgy about it (apart from the spelling). He has a few theories. “A lot of the country that was left uncleared around here was considered unproductive, too rocky or too heavy soil – a bit dodgy, so to speak,” he says.

But why purchase a 742ha property with barely a tree left standing? “For us, buying Dodgey Downs was a great linkage area and allowed us to connect Red Moort to other places,” Alex says. “It’s pretty thrilling to think that we can connect up the bush at Monjebup Reserve on the ridge, all the way through Dodgey Downs to Red Moort, and broaden our connectivity.”

I have another nagging question: what’s the point of it all, this painstaking and expensive exercise in reclaiming native habitat? What if it amounts to little more than a hillside of struggling shrubs?

The hit-and-miss nature of revegetation was evident at Monjebup, which Bush Heritage purchased in stages from 2007. Large tracts of heavier soils were successfully restored, but sandy soils proved tricky until it was decided to try infilling with Proteaceae species such as banksia and hakea.

We visit Monjebup the following day. Alex leads us to a stand of oddly shaped cauliflower hakea (Hakea corymbosa) laden with sweet-scented flowers and edible nuts. They’ve become a ‘lolly shop’ for Carnaby’s cockatoos, the south-west’s large and endangered black parrots.

“This area is now our jewel in the crown,” Alex says. “We’ve got honey possums creating their little nests in this prickly species. They rely on nectar all year round, so also having a rich variety of flowering gums and bottlebrushes is important for them.” He says the orange-flowered Noongar chittick (Lambertia inermis) is a key local species for honey possums “because it flowers when others aren’t”.

These days, Monjebup is teeming with life. We dive between the shrubs and search for shoebox-sized nesting boxes mounted on star pickets. “We’ve got 100 boxes for pygmy possums to nest and breed,” Alex says. “Each year most will have nests in them, with up to five or six [possums inside], including mum and dad.”

Alex lifts the lid of a nesting box and moves aside for us to peek in. We glimpse furry faces peering up through warm, dense leaf litter. It’s an utterly adorable family of five pygmy possums. Further on, we push through shoulder-high bushes to reach an earth mound as expertly contoured as an artist’s sculpture. Gnow, or malleefowl (Leipoa ocellata), build these huge mounds to nurture their young. As clearing advanced, they retreated into remnant bush and are now returning to restored areas.

“We did bird surveys at Monjebup before revegetation and we recorded six species of birds, then five years later we were getting 60 bird species,” Alex says. “We’re starting to get more bird types in the revegetated areas than in remnant bushland that was never cleared!

“With climate change, we know that genetic diversity in fauna and flora is important. But isolated pockets and fragmented landscapes don’t do that as much. A quarter of the species that grow at Monjebup don’t exist at Red Moort. So what we know is that if we plant according to soil types, and according to species surveys, we get great results. We’ve now got over 1000 native flowering species over the five reserves we manage, covering 6330ha. We’re creating resilience, spreading the genes around.”

Carbon sequestration is another part of Bush Heritage’s mission. On the perimeter of Ediegarrup’s paddocks is a visible sign of bad carbon offset from earlier days. A row of eucalypts, devoid of any life other than the occasional perching bird, represents the Western Australian Government’s Forest Products Commission’s approach to sequester carbon and provide timber. No other animals lived here.

This old model has given way to a new Bush Heritage model that strives to achieve much more – carbon capture in a restored landscape full of wildlife. To achieve this, Bush Heritage must meet the stringent standards of the Society for Ecological Restoration Australasia and the Clean Energy Regulator.

“Carbon credit units have to be monitored and audited properly to ensure carbon is sequestered at the site and managed and maintained – in our case, for 100 years,” Alex says. “What we’re doing isn’t just good for the climate but also good for nature.”

Gondwana Link

Half a dozen wallabies graze at dawn, their dainty silhouettes dark against a silver dewy haze. It’s clear to me that Bush Heritage’s cluster of properties deserves its place in Gondwana Link, the largest and most ambitious ecological restoration program in Australia – and possibly the world.

I ask Alex if Bush Heritage has experienced pushback from farmers saying “no more land grabs for nature”. And, one day, will enough pockets of land be covered in green? He says nobody should view their activities as some sort of manic greenie takeover of the landscape.

“We do get questions about taking up prime land, but we’re only looking strategically at land adjoining our reserves or offering a key linkage to an existing vegetated area,” Alex says. “We pay commercial rates and compete with other farmers to buy these properties. For Dodgey Downs, we paid close to $4 million for 762ha, of which 600ha is cleared. We need to ensure we’re buying something in the right place and that we’ll maximise the benefit.

“A lot of farmers respect the bush and its native animals out here – the wedge-tailed eagles that soar above, the chance spotting of a tammar wallaby. They accept that they are part of the landscape, and they want to see sustainable agricultural practices. People can see that the little bits we’re doing in connecting fragmented areas are repairing damage done 50 years ago.”

Gondwana Link CEO and co-founder Keith Bradby agrees with Alex. “It’s easier to farm sustainably in a sustainable landscape,” he says. “You don’t have to have ecological apartheid, with no wildlife on farming land and no farming amongst wildlife.

“In WA we face a biodiversity emergency and a huge need to restore areas, but it’s grossly underfunded. Our projects are carbon-enabled; it’s work that needs to be done and it can be in synergy with carbon targets. What’s happening at Ediegarrup and other properties provides carbon benefits – and ecological, cultural and social benefits.”

Keith believes that Gondwana Link, and Bush Heritage’s part in it, will lead to more disaster-proof landscapes. “Endless expanses of cropping land are fragile landscapes, but these areas of bush being added are as tough as old boots,” he says. “My view is that after year six or seven, they can withstand anything – fire, drought – and you get wildlife back. That’s multiple benefits, with private donations and carbon being the main enablers in the absence of other funds in Australia. This isn’t the old model of locking up bits of bush. It’s landscapes coming alive with the plants, wildlife and new forms.”

Alex says he loves working in the south-west, where he recently discovered the signature of his grandfather, also named Alex Hams, on an old title to a Bush Heritage property.

“It’s kind of nice. My grandad did a lot of clearing for agriculture, but he was very conscious of not clearing bits that weren’t going to be productive and leaving buffers on the creeks,” Alex says. “This area was relatively unchanged for millions of years. Then in less than 70 years whitefellas have come in and cleared the lot. And now with a strong vision of restoration and the kind support from our donors, we can put the bush back for the next million years. That’s exciting for all of us to be part of.”