Aussie bat research 100 years behind

GIVEN THEIR HIGH PUBLIC profile, we tend to assume that most mammal species were recognised and named long ago. Unfortunately, this simply isn’t so, and my recent taxonomic research on the body shape of the greater long-eared bat (the bat formerly known as Nyctophilus timoriensis) illustrates some of the issues that apply more generally to Australian mammals and their implications for science and conservation.

Taxonomy is the science of classifying living organisms and it seeks to determine the number of species (biodiversity as it’s now called) and their uniquely distinguishing features. Yawn! Have I lost you yet?

True, taxonomy might not inspire the same excitement as, say, bungy jumping, but the capacity to recognise and identify species is a vital starting point and a critical foundation for managing and conserving biodiversity effectively.

100 years behind the USA

Our knowledge of Australian bat taxonomy is roughly at the stage of American bat taxonomy 100 years ago. It’s not that our Aussie mammal taxonomists have been out to lunch, but Australia has a shorter history of European settlement than the USA, and a smaller population, and we have at least twice as many bat species to sort out.

The USA has about 45 bat species. The number recognised in Australia has progressively increased and in one human lifespan has doubled from 48 species in 1941 to around 85 in 1997. Currently we are not sure how many species exist in Australia, but at least 90 are known and quite a few of these remain unnamed and poorly diagnosed, as this remains a neglected area of research.

Identifying and describing species is not just an exercise in scientific stock taking – it has significant management implications for conservation and monitoring environmental changes.

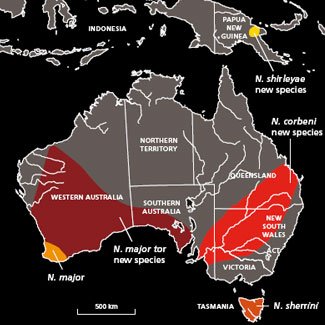

Take the taxonomy of the greater long-eared bat, once thought to be a single species, Nyctophilus timoriensis and widely distributed throughout Australia, New Guinea and Timor. It has recently been shown to consist of four distinct species, one of which also has a

distinct inland subspecies (see map). Furthermore, each of these has a restricted distribution (which does not include Timor, despite the original species name timoriensis) and their habitats vary from rainforest to semi-arid woodland. What this means is that each species has its own conservation needs.

Ranges of the four newly discovered species (and one subspecies) of greater long-eared bat

It’s time to turbo-charge taxonomy

Are bats a special case of our taxonomic ignorance, given that most species are small, nocturnal, and easily overlooked? I wish that were true, but there are strong indications that the taxonomy of other groups of Australian mammals also needs to be thoroughly re-examined. Recent molecular studies have shown that even conspicuous, widespread animals from more populous areas of Australia are not what we think, with a new species of brushtail possum, Trichosurus cunninghami, recognised from Victoria and New South Wales in 2002.

Australia, with the rest of the globe, is facing an imminent extinction crisis as the pressure from humanity continues to build on the biosphere. Some animals will become extinct before they are even recognised as distinct species. We should be redoubling our efforts to clarify the number of mammal species at such a critical time but, sadly, support for mammal taxonomy and Australian vertebrate taxonomy generally has declined over the past 20 years.

The widely held assumption that the work was completed decades ago remains a stumbling block that could ultimately be as much a threat to biodiversity conservation as the more immediate threats of land clearing and coastal urbanisation.

Dr Harry Parnaby is a research associate specialising in mammals at the Australian Museum in Sydney. This opinion piece is an edited version of a story first published by the museum’s Explore Magazine.