Saving Nemo: how climate change threatens anemonefish and their homes

ANEMONEFISH, OR CLOWNFISH, were made famous by the 2003 Disney-Pixar film Finding Nemo, and are about to play a starring role in the sequel, Finding Dory. They are well known for their special relationship with anemones, which provide a safe place to call home.

But anemonefish face a number of threats. Some researchers have warned of an increase in the wild-caught anemonefish trade, as happened following Finding Nemo.

Anemones, on which anemonefish depend, are threatened by warming seas in a similar way to corals. In fact anemones were affected by the recent coral bleaching on the Great Barrier Reef, which recent updates show has left a third of coral colonies dead or dying in the north and central parts of the reef.

So will Nemo be left homeless?

A healthy (left) and bleached (right) bubble-tip anemone (Entacmaea quadricolor) on the Great Barrier Reef. (Image: Ashley Frisch)

Nemo and his 27 cousins

There are 28 species of anemonefish. Although some people call this group “clownfish”, technically this name is only used for one species, Amphiprion percula. “Nemo” (A. ocellaris) looks similar, but is actually known as the “false clownfish”.

Anemonefish are famous for their special relationship with anemones. Although they can survive in aquariums without anemones, in nature they rely on anemones for protection from predators.

The pink anemonefish (Amphiprion perideraion) in a bleached anemone (Heteractis magnifica) at Christmas Island. (Photo credit: JP Hobbs)

In return for providing a safe home, the resident anemonefish will provide nutrients and defend the anemone from predators such as butterflyfish. Both the number and size of anemonefish is linked to the size and number of anemones – and vice versa. Therefore, any decrease in one partner affects the other.

The collection of anemones and anemonefish for the aquarium trade has to be managed properly to ensure the future of anemonefishes. Anemonefish can be easily bred in captivity and this provides a reliable source for aquarium enthusiasts without impacting wild populations.

Cinnamon anemonefish (Amphiprion melanopus) in a bleached anemone (Entacmaea quadricolor) on the Great Barrier Reef. (Photo credit: Ashley Frisch)

Ten species of anemones are inhabited by anemonefish. The highest diversity of anemonefish occurs in Indonesia, where anemonefish species outnumber anemones. As a result, different species of anemonefish have learnt to share the same anemone.

In most other locations, anemonefish aggressively prevent other species from entering their anemone. Anemonefish species differ in the number of anemone species they associate with.

Clark’s anemonefish (Amphiprion clarkii) in a bleached anemone (Cryptodendrum adhaesivum) at Christmas Island. (Photo credit: JP Hobbs)

Clark’s anemonefish (A. clarkii) can live in all ten anemone species and is widely distributed throughout the Indian and Pacific Oceans. In contrast, McCulloch’s anemonefish (A. mccullochi) inhabits only one species of anemone and occurs only on reefs around Lord Howe Island.

After hatching, anemonefish larvae use their keen sense of smell to find their preferred anemone species and avoid unhealthy (bleached) anemones.

Anemones in hot water

Anemones are closely related to corals and get their colour from microscopic algae (zooxanthellae) that live symbiotically within the tissue of the anemone. Like corals, anemones expel their algae and turn white when they become stressed.

This process – termed “bleaching” – is usually in response to periods of elevated seawater temperatures. All ten species of anemones are susceptible to bleaching, which can result in a decrease in the size and number of anemonefishes and reduced reproduction.

McCulloch’s anemonefish (Amphiprion mccullochi) in a bleached anemone (Entacmaea quadricolor) at Lord Howe Island. (Image: Justin Gilligan)

If seawater temperatures remain high for too long, then bleached anemones will die. In 1998, a prolonged period of elevated water temperatures in Japan resulted in mass mortality of bleached anemones and local extinction of anemonefish.

In March 2016, the Great Barrier Reef experienced a severe bleaching event due to elevated water temperatures associated with a strong El Niño event. There was mass bleaching of both corals and anemones.

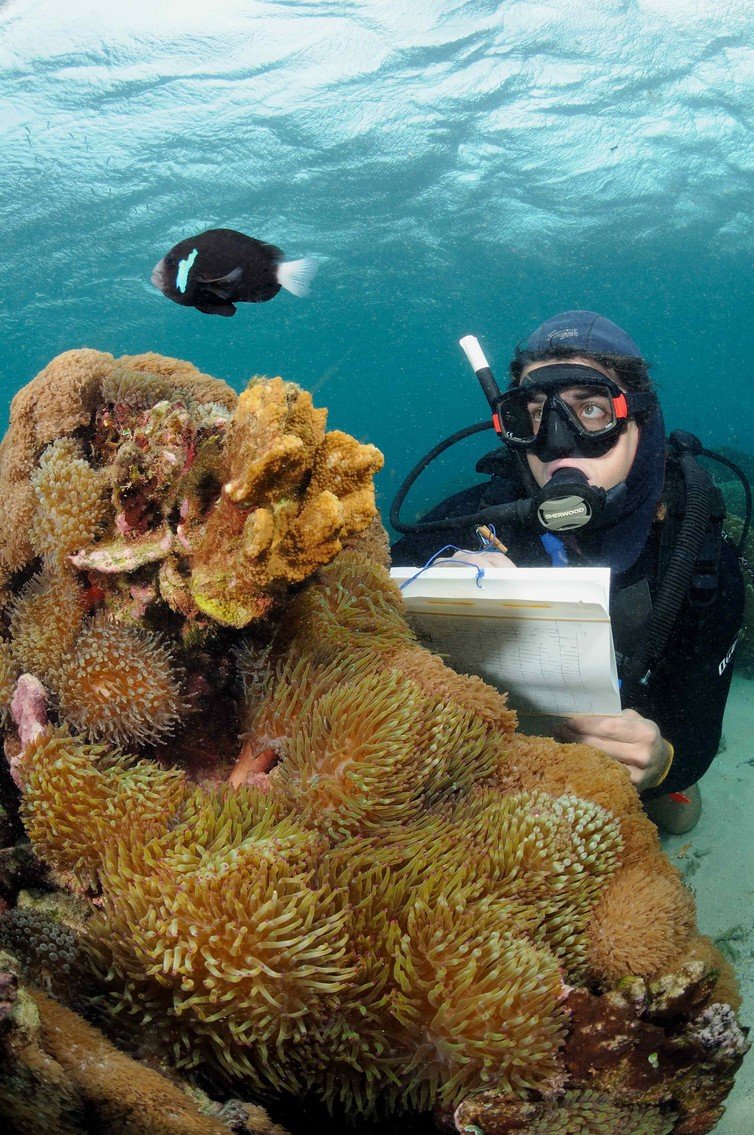

Marine biologist Jean-Paul Hobbs studying anemonefish (Amphiprion mccullochi) and their host anemones (Entacmaea quadricolor) at Lord Howe Island. (Photo Credit: Justin Gilligan)

In April 2016, elevated water temperatures also caused mass bleaching of corals and anemones off north-west Australia, including Christmas Island. Bleached anemones have also recently been reported elsewhere in the Pacific Ocean, Indian Ocean and in the Red Sea.

The future of the bleached anemones and their resident anemonefish will depend on how quickly the water temperature returns to normal. If the temperature decreases swiftly, bleached anemones can regain their colour (reabsorb zooxanthellae) and survive.

However, the frequency and intensity of bleaching events are predicted to increase as the climate changes. Consequently, there are serious concerns about the ability of anemones and anemonefish to cope with rising water temperatures.

Reducing global greenhouse gas emissions will limit subsequent bleaching events and help ensure the future of Nemo and its relatives.

![]()

Jean-Paul Hobbs is a Research Fellow at the Department of Environment and Agriculture, Curtin University and Ashley J Frisch is a Postdoctoral Fellow in Marine Ecology at James Cook University.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

READ MORE:

- Great Barrier Reef bleaching almost impossible without climate change

- Finding Nemo’s personality

- In pictures: A close-up look at the Great Barrier Reef’s bleaching

- Corals that can stand up to climate change

- Lord Howe Island: life on Lord Howe