AT ABOUT NINE o’clock on a 1993 spring night, a truck was travelling eastwards along the Lyell Highway through the Tasmanian Wilderness World Heritage Area. Half a kilometre past the Franklin River bridge, the driver* negotiated a bend and then a rise. At the top of the rise, his headlights lit up the dead-straight roadway as bright as day.

That’s when he saw it. As he reported the next day, a dog-like animal was crossing the road about 100m ahead. Coming closer and slowing down, he noticed dark vertical stripes on its brown body. In the driver’s mind there was no doubt: it was a Tasmanian tiger, a thylacine. But was this possible? The species – the world’s largest marsupial carnivore of recent times – was officially extinct.

Before the truck reached it, the animal turned back to the roadside. The whole sighting lasted perhaps six seconds. Fast-forward to 2016. I’m standing where, according to the truck driver, the animal left the road. Behind me is dense bush; in front, on the other side of the road, is a sweep of button grass plain called Wombat Glen. Beside me is Nick Mooney – lean, grizzled, ebullient and eloquent.

Nick was a wildlife officer for the Tasmanian Parks and Wildlife Service until 2009 and is now an independent wildlife biologist. He has investigated thylacine sightings for 35 years and is an acknowledged authority on the species. The truck driver’s sighting was one of his cases.

“He was a normal truckie without the slightest vested interest in faking it,” Nick says. “He was totally convinced about what he saw and thought we should know.”

After visiting the site with the driver, Nick returned with a dog, with which he retraced the mystery animal’s steps to calculate how long it was in the truckie’s sight. “His reported timing almost exactly matched what I worked out with the dog. That shows he was a good observer and hadn’t exaggerated,” Nick explains.

The sighting followed a familiar pattern. Most sightings happen at night and on roads, because roads attract animals and these days there are more people on roads than in the bush. They usually happen as a vehicle rounds a corner, catching an animal by surprise. Many reports are unconvincing, but a few give the experts pause. In March, biologists from James Cook University announced a new study to investigate two plausible sightings in Cape York, raising the tantalising possibility that a thylacine population survives on the mainland.

The Franklin River area produced several reports in about 1990, Nick says. “There were four or five on this stretch of road. There was a truckie, a tourist, a guy on a motorbike early in the morning… They didn’t know each other, which adds credibility. One can be sensibly sceptical but I’m always reluctant to dismiss any half-decent report.”

The extinction of the Tassie tiger

THE EXTINCTION OF the thylacine was the tragic climax of a clash between Tasmania’s European colonists and an ecosystem they seriously misunderstood. Conventional wisdom has it that by 1803, when the first settlers arrived on the island, thylacines had already been extinct on the Australian mainland for some 2000 years. Nick Mooney estimates there were about 2100 on the island, and colonists didn’t come into contact with them until 1805, when a pack of dogs killed one.

From then on this so-called Tasmanian wolf or hyena instilled an irrational fear in residents, mostly arising from their total ignorance of the animal. They saw it as a mortal danger both to livestock – mainly sheep – and themselves. So they began savagely evicting it from its ancient habitat – shooting, snaring, poisoning and trapping it.

By 1909 thylacines were scarce, the slaughter having been hastened by a government bounty scheme that paid out on 2184 carcasses. The last to be killed in the wild was shot in 1930 by farmer Wilf Batty. The last one caught in the wild was sold to Hobart Zoo in 1933. It died there on 7 September 1936 and was thought to have been the last of its kind. In 1982 the International Union for Conservation of Nature declared the thylacine extinct and in 1986 the Tasmanian government followed suit.

Above you can see the recently rediscovered footage of Benjamin found in 2020 by the National Film and Sound Archive. You can read the full story of it’s rediscovery here.

But that’s not the last chapter in this sorry saga. Nick Mooney says it’s “entirely possible” 100 or more thylacines may have survived in the wild after 1936. A 2016 study published in Australian Zoologist concludes that some may have been around through the 1940s and perhaps later. Since then sighting reports have continued – more than 900 since 1936 in Tasmania and reputedly a similar number from the mainland. Interestingly, most mainland reports are from the south-east and far south-west.

People who report sightings come from all walks of life and many have little prior knowledge of the creature they say they’ve seen. Few seem to have an ulterior motive for making a false report, such as a desire for fame, money or to perpetrate a successful hoax. They genuinely believe they saw a Tasmanian tiger.

Aside from these many one-off witnesses, there are a number of dedicated tiger-seekers, both in Tasmania and on the mainland, who spend a lot of money and time searching for what has become one of the world’s legendary creatures.

A proportion of these can be said to be ‘true believers’ who have absolutely no doubt the tiger is alive. Some say they have seen it; others believe they have been close, either because they have smelt its pungent scent or heard its unusual calls. All hope that incontrovertible proof of the tiger’s continued existence will one day surface. And the best proof would be a live animal.

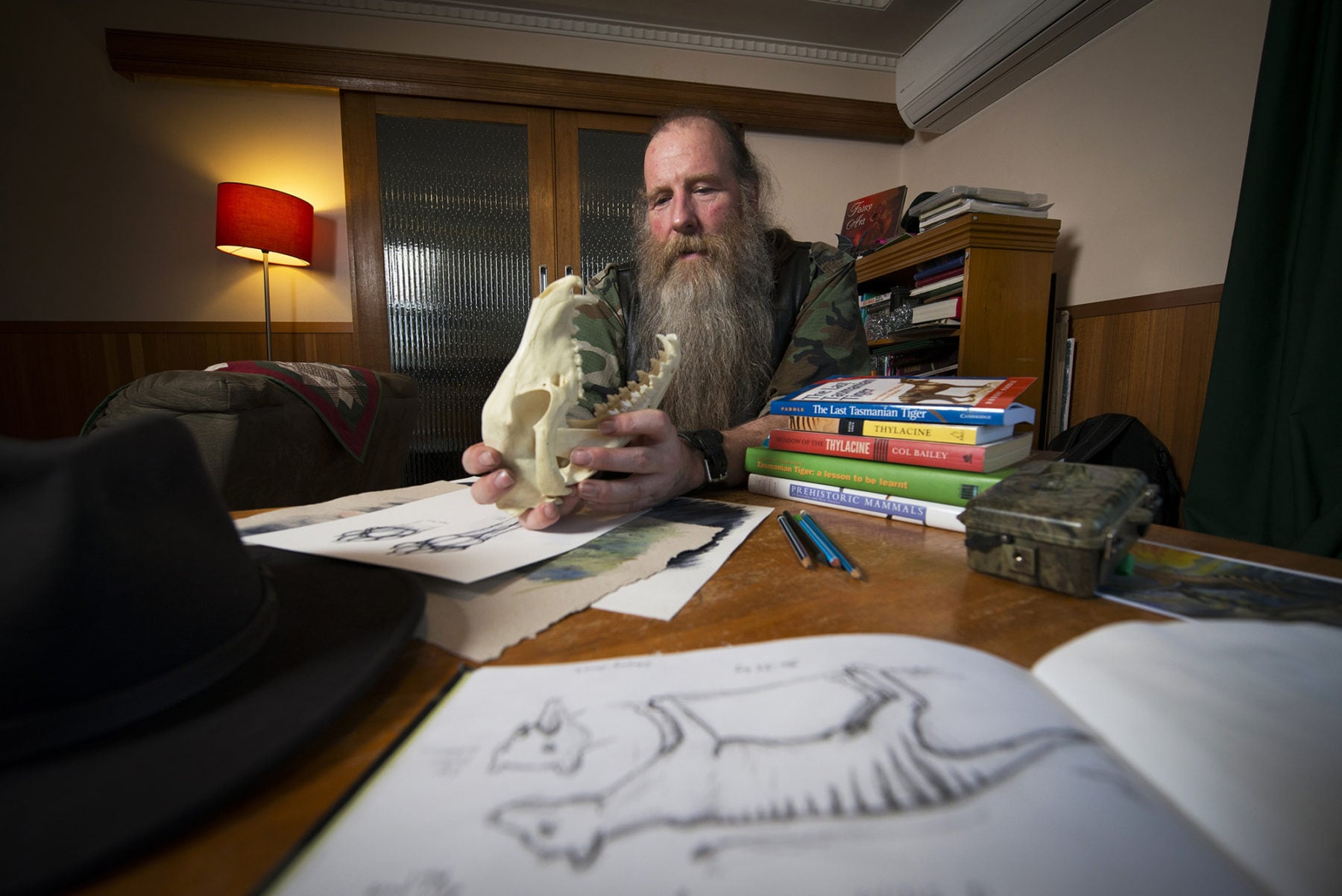

The doyen of the true believers is Col Bailey, a retired landscape gardener, life-long bushwalker and canoeist and author of three books about the thylacine. His most recent, Lure of the Thylacine, was published in 2016. Col is almost 80. When I meet him in Hobart at the Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery (TMAG), site of one of the world’s largest thylacine collections, he says that after 50 years of searching for the tiger, it’s time to hang up his bushwalking boots. But he’s not short of energy for talking.

He recounts that, in 1967, at the age of 30, he was canoeing on South Australia’s Coorong wetlands system when he spotted a dog-like animal on a beach 200m away. It had a heavy head, low-slung body and long tail that seemed to drag on the sand. “I thought, what is that thing?” he recalls. “To this day I’m not sure what it was. But it got me interested enough to inquire about it.”

Col’s investigation pointed to the thylacine and he’s been researching and seeking it in Tasmania ever since. Stories of old-timers who were acquainted with the tiger provide material for his books. So do his own bush experiences, including a claimed sighting in 1995 while he was camping in remote south-western Tasmania.

It happened one morning while he was having “a quiet snoop around” after hearing strange calls. At one point he saw what looked like a feral dog, but then he followed it and got a better view. “I attracted its attention and it turned to look at me,” he says. “My eyes ran down its back and I saw those stripes near its tail. I knew then what it was.”

Col has been on a half-century quest to prove the thylacine exists. So far, like every other searcher, he’s failed to come up with watertight evidence. But he’s unfazed. “I can’t prove it exists and the sceptics can’t prove it doesn’t exist,” he says. “It’s definitely still there. I know.” And that’s enough for him.

Proof and its absence are a recurring theme in an 80-page book, Magnificent Survivor – Continued Existence of the Tasmanian Tiger, originally published in 2004 and available free of charge online. Its author is ‘Tigerman’, a Tasmania-based thylacine researcher who insists on anonymity. He describes himself as a greenie, an egotist and a dreamer.

As the book’s title proclaims, it is an undisguised attempt to prove that the thylacine survives. It’s based on research the author says he carried out over six years.

In the absence of absolute proof that the thylacine exists today, Tigerman harnesses ‘sub-proof’ – such as footprints, tail drag marks, cave lairs, scats and prey carcasses – to make his case. He believes about 200 Tasmanian tigers exist in three separate groups on the island, 100 in the south-west, 70 in the north-west and 30 in the north-east.

“It is almost extinct, but not quite. I know that because I have seen two,” he writes. But, he adds, “society will not protect an animal it thinks is extinct. If the Tasmanian tiger is to survive, someone must prove it exists…”

In the Blue Mountains of NSW I visit the book-crammed home of Mike Williams, a fast-talking bundle of infectious exuberance. Though a mainlander, he’s been searching for thylacines in Tasmania since the early 2000s. His interest was originally an offshoot of his fascination with so-called cryptids, creatures that cryptozoologists believe exist but that have not been proved to do so. It’s a fascination he shares with his partner, journalist Rebecca Lang, with whom he produced and published a book in 2010 about mysterious big cats reportedly roaming the Australian bush.

“While we were investigating big cats we started to get reports about thylacines,” Mike says. “We went to Tasmania and I spoke with Col Bailey initially, then with others, and heard of some interesting and even bizarre sightings by really good witnesses. Not all of them are deluded or demented. That started me on my hunt for the tiger.”

Mike began following up sightings. He has made numerous trips to Tasmania, four of them for major expeditions. He has a fifth expedition planned for 2017. “I will chase up more witness reports and set up three to five cameras at different sites and come back and check them later,” he says.

Although he doubts the thylacine survives on the mainland, he’s sure it does in Tasmania and believes that sooner or later a dash cam on a local’s car or a camera trap in the bush will confirm this. “I am convinced it’s out there, otherwise I wouldn’t waste my time,” he says.

In 2014 Mike and Rebecca published a book of essays by different authors entitled The Tasmanian Tiger: Extinct or Extant?

Thylacine sightings

Thylacine sightings have been reported in all mainland states, but Victoria is a hotspot. One Victorian who’s contributed his fair share is Murray McAllister, a physical education teacher at a Melbourne secondary school. In 1998 he was writing a novel about some children trying to prove the tiger was alive. While researching his topic, he learnt there had been 54 thylacine sighting reports from Loch Sport, a small township on the Gippsland Lakes.

“I decided to live the dream of the children in my novel,” Murray tells me. “I was going to prove to the world that those animals are still there after decades of presumed extinction.

“I decided to go down there. On my first visit I stayed three days and had my first sighting. So it was destiny.

I thought if I kept going there I’d eventually get what I was after.”

Murray says he’s seen the thylacine 20 times since then and almost trapped it once. Even so, he feels his dream has only partly come true because, despite leaving five top-of-the-range cameras in the bush for months, he hasn’t captured a convincing image of his quarry.

Murray believes the only answer is to catch one. “Then I’ll build a cage around it, take hundreds of photographs and lots of video, get hair samples and video myself releasing it,” he says. “That’ll be the evidence I need.”

In Toolangi, about 35km north of the school where Murray teaches, lives Bernie Mace, a former industrial scientist with a lifetime interest in natural history. While working in Tasmania in 1966–69 he heard what he believes are credible reports of thylacine sightings.

“I’d gone there convinced the thylacine was extinct,” Bernie says. “But those reports persuaded me it might still be around. That was the beginning of my journey.”

On returning to Victoria, Bernie began hearing reports of sightings in his home state, particularly in East Gippsland. Ever since, he has been following up the better reports in Victoria as well as other states including Tasmania. “I’ve been developing long-range spotlights and investing in night-vision goggles,” he says, “and I have half-a-dozen motion-sensor cameras.”

He’s writing a book about his 50 years of thylacine research and is reluctant to reveal too much before

publication. However, he hints that it will contain key evidence about the thylacine’s survival: “I’ve heard vocalisations over the years that convinced me something unusual was around.”

Thylacine Research Unit

Hope is the fuel that powers all true believers. But not only them. Among tiger-seekers there are some who are not sure if the animal survives. They keep an open mind and are more likely to question evidence. Even so, they allow themselves to hope now and then. Interestingly, so do many sceptics.

Bill Flowers was a sceptic once. A mountain of a man with a measured manner of speaking and a torrent of greying hair, Bill is a member of the Tasmania-based

Thylacine Research Unit (TRU). The three-man group aims to apply a scientific approach to evidence and embraces technology such as night-vision gear, trail cameras, listening devices and drones. It maintains a website where the public can report sightings.

Bill is an artist, filmmaker, herpetologist and wildlife carer with a particular interest in Tasmanian devils. The other TRU members are Chris Coupland, a zoologist, conservationist and filmmaker, and Warren Darragh, an IT professional and former telecommunications officer with the Australian Army.

Bill says the trio started out by investigating and debunking myths about the tiger. All were initially sceptical about the animal’s survival, but then Bill had a

couple of experiences that punctured his conviction. One was hearing a mysterious animal call in prime thylacine habitat while investigating a sighting report in 2015. The other was seeing a plaster cast reportedly made in the 1980s of a young thylacine’s footprint. In appearance it matched almost exactly a sketch he’d made of a thylacine foot in the TMAG.

If thylacines were still around in the 1980s, they could have survived till the 21st century, Bill reasons. “That was earth-shattering for me,” he says.

Not that he’s now a true believer. “I err on the side of probable extinction. Most likely they’re extinct, but there’s a chance they’re not.”

Extinct or not?

So, are they unquestionably extinct? Or might a few be holding out in remote bushland somewhere? Unfortunately, despite the hopes, dreams and prodigious efforts of a surprising number of people, there’s not a shred of conclusive proof of this possibility – no convincing photographs or video, no verifiable footprints and no roadkills.

“Nowadays fast roads go through just about all the high-quality thylacine habitat and there are plenty of reported sightings, so we should have had a roadkill by now,” Nick Mooney says.

Kathryn Medlock, senior curator of vertebrate zoology at TMAG in Hobart, agrees. Even though there are more people in Tasmania than ever and hundreds of remote cameras (up to 500 by some estimates) operating in the bush at any one time, none have come up with any convincing evidence, she says.

“All the fauna people do their surveys using remote cameras,” Kathryn explains. “They’d be the first to say if they’d photographed a thylacine. There are hundreds of thousands of roadkills every year but none of thylacines. There’s not even a manky skeleton that’s been lying beside a road for 20 years.”

Tammy Gordon, the collection officer at the Queen Victoria Museum and Art Gallery in Launceston and co-author of the book Tasmanian Tiger: Precious Little Remains, says no thylacine has been brought to the museum in the past 80 years. “The museum has a file of sightings dating from the 1930s, but in the 30 years that I have been here I have not seen anything I would consider evidence.”

And yet the search goes on. Why? Are tiger-hunters deluding themselves? Are the true believers too starry-eyed to face the facts? What drives them?

Some searchers may have quite basic motives, such as a desire for fame, notoriety or fortune. Others say they love the bush and that looking for the thylacine gives them a good excuse to be in it. But a number raise more complex issues. “By searching for this animal I feel I’m honouring its existence,” Mike Williams says. “We treated it savagely, we did horrific things to it, but if we find it we’ll know we haven’t destroyed it and could say we humans aren’t as bad as we thought we were. It would be a form of redemption.”

Eric Schwarz, a senior wildlife management officer in Tasmania’s Department of Primary Industries, Parks, Water and Environment, agrees. “There’s definitely an element of guilt in this,” he says. “I think people hope that a wrong will be righted by the knowledge that we didn’t exterminate it. It’s almost as if we’d be exonerated.”

“A stunning example of over-optimism”

After 35 years of thylacine work, Nick Mooney remains open-minded. “It could be out there, but it’s unlikely,” he says. “On Mondays, Wednesdays and Fridays I think it’s there, on other days it’s not. If somebody found one, I would be elated but not surprised. Perhaps we haven’t found it yet because we are simply much less good at finding very rare things than we think we are.”

Kathryn Medlock would be overjoyed if one were found. But she’s not optimistic that government bodies or the public would ever hear about it because most tiger-searchers insist they’d tell no-one if they were successful. And that means the myth of the thylacine’s survival will probably never die and the hunt will go on forever.

In 1986 AG 3 carried an 18-page feature about the Tasmanian tiger written by Andy Park. In it he quoted Michael Archer, currently a professor at the University of NSW School of Biological, Earth and Environmental Sciences, and a former director of the Australian Museum, where he became involved in a plan to clone the thylacine. The belief that the species survived, Michael told Andy, was “a stunning example of over-optimism”.

But 30 years on, Michael wrote the foreword for Col Bailey’s latest book and in it he generously praises Col for his absolute conviction that the tiger survives. Then he adds, “With all my heart, I hope he is right.”