Friend or foe: How bottlenose dolphins keep track of their social alliances

In life it pays to keep a close eye on competitors and rivals. Historian Doris Kearns Goodwin’s book, Team of Rivals, tells how US president Abraham Lincoln persuaded each of his political rivals to join his cabinet, thereby turning them into his allies.

But the formation of alliances with potential competitors is not unique to humans. In a study published in Current Biology, my colleagues and I describe how such behaviour is also found among bottlenose dolphins.

We found that individual male dolphins retain their unique signature whistle, allowing them to recognise many different friends and rivals in their social network, something not currently known from any other non-human animal.

The Shark Bay network

In Shark Bay, Western Australia, pairs and trios of unrelated male dolphins work together in alliances to herd single females for mating opportunities. On a second level, teams of alliances work together to steal females from opposing alliances and to defend against such theft attempts.

The males are therefore cooperating with individuals with whom they are in direct reproductive competition, since paternity success cannot be shared. But the bonds between these teams of rivals are as strong as those between mothers and calves, and these friendships and alliances can last entire lifetimes.

So how do these males keep track of all these different relationships, and how do they maintain such strong social bonds? The answer may lie closer to home than you think.

Vocal labels for dolphins

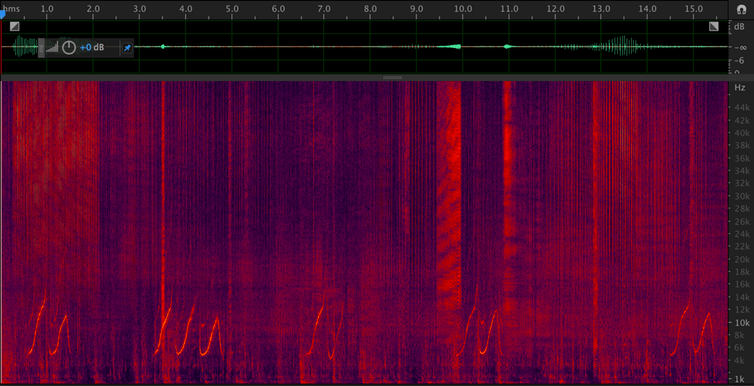

Previous research has shown that bottlenose dolphins develop an individual vocal label known as their signature whistle, which they use to broadcast their identity.

These dolphins aren’t born with their own signature whistle. Rather, each dolphin develops a signature whistle within the first few months of life that is structurally unique from those of its companions.

It has been shown that these signature whistles are somewhat comparable to human names. Dolphins use them to introduce themselves or even copy others as a means of addressing specific individuals.

For decades it was thought that male dolphins would converge onto a shared signature whistle when they formed alliances with one another.

It was proposed that such an alliance signature would allow males to advertise alliance membership to competing males or to sexually receptive females. A type of vocal badge or group label.

Intriguingly, we found that male dolphins in Shark Bay retain individual vocal labels distinct from their allies.

Individually ‘named’ dolphins

This is an unexpected finding as it is well known that animals that form strong social bonds will vocally accommodate one another, making their calls more similar. By doing so, animals are not only advertising the strength of their relationships but also their group membership.

Such vocal convergence is found in many animals including parrots, songbirds, bats, elephants and primates.

Yet, it appears that in the complex network of dolphin alliances in Shark Bay, retaining individual “names” is more important than sharing calls. It allows male dolphins to recognise many different friends and rivals in their social network.

Even within these dolphin alliances males can show preferences and avoidances for with whom they cooperate.

Bottlenose dolphins have been shown to remember the signature whistles of other individuals even after 20 years of separation. This long-term social memory combined with the use of individual vocal labels, allows dolphins to keep track of many different relationships, as well as the history of those relationships.

Our research suggests that vocal labels play a central role in the recognition of cooperative partners and competitors in biological markets.

Male bonding, dolphin style

If allied male dolphins do not converge onto similar calls, then how do they reinforce their strong bonds?

Well, males in Shark Bay invest a lot of time in gentle contact behaviours, such as petting.

This may be similar to grooming behaviour in primates, which has been linked to oxytocin release. Oxytocin is a hormone that is known to facilitate social bonding between both humans and non-human animals, as well as promoting both trust and cooperation.

Dolphin alliances in Shark Bay are also characterised by high levels of synchronous behaviour. Males in alliances can perform the same behaviours at exactly the same time, surfacing in precise synchrony or performing coordinated displays.

It appears that synchrony, rather than shared calls, is what represents alliance unity.

In human societies, synchronous behaviour, such as choreographed dancing, military marching or parades, is believed to have evolved to signal the quality of relationships.

![]() It appears, then, that the multi-level dolphin alliances in Shark Bay share some traits with humans societies, where individual vocal labels help with the recognition of cooperative partners, and synchrony is a signal indicating the strength of those partnerships.

It appears, then, that the multi-level dolphin alliances in Shark Bay share some traits with humans societies, where individual vocal labels help with the recognition of cooperative partners, and synchrony is a signal indicating the strength of those partnerships.

Stephanie King is a Branco Weiss Research Fellow at the University of Western Australia.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.