BULL SHARKS IN Moreton Bay are a very good sign for Brisbane. The waters of this subtropical east coast waterway are as close as 14km to the city’s CBD, and the coastal lands that fringe its westerly edge have been impacted by European settlement since the late 1800s.

These days there is ever-growing pressure on the natural ecosystems here, with the bay – which extends about 125km, from Surfers Paradise on the Gold Coast in the south, to Caloundra on Queensland’s Sunshine Coast in the north – being on the doorstep of Australia’s fastest-growing urban strip.

Because they are top-order predators, bull sharks are sensitive indicators of environmental change. So having them around is a sign of a healthy ecosystem, Johan Gustafson from the Griffith Centre for Coastal Management, explains reassuringly.

The mouths of rivers feeding the popular waters of Moreton Bay comprise an important bull shark nursery area. Pregnant females arrive in the warmer months to give birth and their pups grow here, feeding on small fish in the dark estuarine waters before migrating offshore as adults.

Understanding the significance to the bull shark life cycle of alternate artificial coastal habitats in the area is crucial for determining the impact of coastal development on this threatened, and potentially dangerous, species.

There have been two recent documented human fatalities attributed to encounters with bull sharks in the canal and artificial lake systems of the Gold Coast.

Griffith University researchers suggest that, with increased impacts on the natural environment, artificial coastal habitats are becoming used more by large juvenile bull sharks, increasing the chance of interactions between these predators and people.

“Moreton Bay is becoming more developed especially around the mangroves, where there is also a lot of shipping and recreational fishing,” Johan explains. “By removing the seagrass and mangrove areas along the coast, we could be removing the shark’s preferred habitats.” And that means they’re likely to look elsewhere for food.

Previous tagging studies on bull sharks from the Gold Coast region have shown that this species prefers to inhabit healthy estuarine systems with enough prey to support them, rather than the artificial canals and lakes.

However, because the sharks occur naturally in adjacent areas, they will often move into adjoining artificial habitats. An incentive for them is that most of their preferred prey – including tailor, mullet, herring, trevally and bream – thrive in the canals and lakes.

The Griffith University researchers are learning much about how the sharks are using bays and river systems where there is a lot of development. When it rains, for example, more fresh water enters the rivers, resulting in more bull sharks around estuaries.

The team has also observed that larger sharks come into the waterways in September–October when the waters warm, a trigger for females to enter the river systems and give birth.

“Swimmers need to be mindful not to swim or paddle after big rainstorms,” Johan warns. “Rain is a big trigger for the sharks and this information needs to be incorporated into management responses.”

The information may also contribute to the design and engineering of impediments to stop sharks entering built areas during these times, helping reduce the chance of negative interactions between sharks and people.

Fighting for survival

Moreton Bay’s coastal strip is naturally a maze of wetlands, the type of habitat that’s been increasingly threatened worldwide since about the middle of last century.

Here is no exception.

But the good news is, as bull sharks show, many of the bay’s natural wildlife inhabitants are finding ways to survive, often with the help of passionate locals, researchers and conservationists.

Like a natural lung, Moreton Bay draws in salt water rich in oxygen as well as nutrients from the Pacific Ocean and discharges fresh water from the upper reaches of the catchment on the outgoing tide. This tidal ebb and flow is a constant for the marine habitats here, which range from rocky shores, deep reefs, sandy beaches and mudflats to seagrass meadows and mangroves.

Rare humpback dolphins, dugongs and turtles, as well as a range of sharks – including hammerheads and tigers, as well as bulls – shelter in Moreton Bay’s waters, which are protected by some of Australia’s largest sand islands, including South Stradbroke, North Stradbroke and Moreton.

Deeper offshore reefs support a rich mix of both tropical and temperate species. Carpeted partly in a living veneer of complex coral diversity delivered by the East Australian Current from the Great Barrier Reef, these reefs of contrast are also the northern limit for colder-water species, such as the grey nurse shark. This docile fish is often seen by divers in the bay alongside filter-feeding manta rays arriving from the north.

Sheltered from a large ocean swell, Moreton Bay also has a long history of human occupation and use that stretches well back before Europeans arrived to the local Quandamooka people who worked alongside resident dolphins to catch fish. A sea spirit that manifests as a dolphin, Quandamook is an important creator spirit for Aboriginal people here.

Coral mining, sand mining and whaling began after European colonisation and turtles were hunted commercially from 1824 to 1950. A conservation movement focused on the bay began in the mid-1960s, with strong public opposition against plans for a canal estate and further mining. This soon resulted in the first protected areas being declared within Moreton Bay, to conserve habitats from coastal development while still allowing for sand and coral mining and commercial and recreational fishing.

Three decades later, in 1992, after a long campaign by local conservationists, scientists, tourism groups and educators, Moreton Bay Marine Park was declared to protect the area’s unique values while also continuing to allow sustainable use. Park management includes actions such as the development of designated ‘go slow areas’ for motorised boats, to protect turtles and dugongs from boat strikes, particularly in seagrass feeding areas.

The listing last year of Moreton Bay as a Hope Spot brings it wider global attention, which adds another level of protection. The Hope Spot concept was developed by the Mission Blue initiative of internationally famed marine biologist Dr Sylvia Earle.

Supported by Rolex’s Perpetual Planet program, it aims to help safeguard “special places that are scientifically identified as critical to the health of the ocean…championed by local conservationists whom we support with communications, expeditions and scientific advisory”.

Sylvia has visited and dived in Queensland for many years and the recognition of the waters off Brisbane as a Hope Spot are not surprising. The conservation initiative describes Moreton Bay as “a mecca for marine biodiversity” that “hosts tropical, subtropical and temperate species within its matrix of mangroves, mudflats, seagrass, coral reefs, and sand islands.”

A decrease in vital habitats

With slightly more than 3 million people, Brisbane is Australia’s third most populous city, behind Sydney and Melbourne. Being at the centre of a south-east Queensland strip that’s experiencing Australia’s most rapid urbanisation, its population is expected to reach 4–5 million by 2031.

Mostly notably, Brisbane is book-ended by expanding urban centres surrounding the Sunshine Coast to the north and the Gold Coast to the south, all of which are on the shores of Moreton Bay. Most of the population in this area already resides around 15 catchments that drain into the bay.

These waters face pressures from a suite of impacts common to coastal cities the world over. Some are linked specifically to developments such as the incremental expansion of the Port of Brisbane and construction of the Gold Coast Seaway. Others arise from the cumulative impacts of urbanisation and include run-off, sedimentation, stormwater and the deposition of associated marine debris, habitat loss, and increasing watercraft use.

Mangrove forests filter land-based run-off, particularly sediments and nutrients, and help support clearer and cleaner water, which is important for coral reef health and seagrass meadows. It’s also acknowledged that three-quarters of all fish caught in Queensland directly use mangroves or depend on food chains that rely on them.

In the past, the destruction of saltmarsh, mangroves and tidal flats that soften the natural foreshore has occurred due to the creation of some of the largest canal estates and lakes in Australia. Some of these are directly attached to the natural estuarine systems, while others are an extension of the waterway with tidal flows restricted by gates and locks to prevent erosion and allow for the expansion of waterfront property available for development.

These artificial waterways tend to have poorer water quality, limited circulation and more input from untreated stormwater. And as indicated by the Griffith University bull shark research in the area, they affect the ecology and interaction between species found here.

Once viewed as salty, insect-infested eyesores that blocked coastal views and impeded foreshore developments including marinas, ports, jetties and boat ramps, mangrove forests are now being widely acknowledged for their benefits.

The Queensland government has begun implementing management strategies to help address its own historic contribution to the global decrease in these vital habitats.

Notably, that includes a 450m mangrove walk – designed to educate about, and encourage an appreciation for, wetland areas – currently under construction between the City Botanic Gardens and Queen’s Wharf in Brisbane.

Erosion of the Gold Coast

The Gold Coast’s expansive and stunning sandy shores and surf breaks are famous worldwide. Coastal processes work undertaken by the Griffith Centre for Coastal Management during the past two decades has helped preserve important social and economic values in Moreton Bay, often protecting and enhancing the surf breaks and beaches that draw tourists to the area and underpin the lifestyle enjoyed by a growing number of locals.

However, the Gold Coast is also particularly vulnerable to extreme weather events, which often cause significant erosion, and that has been the focus of a long-term program for effective beach management, with which the Griffith Centre has also been involved. Along this stretch of coast, erosion has been an important natural process for many millennia. Sediments are transported northwards, driven by south-east wind and waves.

There can be a difficult balance between allowing the forces of nature have their way and protecting coastal urban landscapes. And so a major focus of the Griffith Centre’s work has been to help ensure ongoing sediment transport continues along beaches that are affected by artificial obstructions, such as tidal entrances that force sand to build up on the updraught side and erosion to occur on the downdraught side.

The Gold Coast Seaway and associated sand bypass system was constructed between 1984 and 1986 to facilitate safe entry for commercial and recreational boats. Although it led to the loss of some estuarine marine habitats, the addition of a large amount of rock has also created an artificial habitat that supports an abundance of marine species enjoyed by divers and fishers.

“There was a need to artificially move sand from one side of the estuary to the other to ensure we didn’t lose South Stradbroke Island and to ensure the continued movement of sand up the coast,” explains Professor Rodger Tomlinson, the Griffith Centre’s founding director.

Natural sediment transport has been critical to sustaining the entire Moreton Bay ecosystem by creating the barrier Islands – South Stradbroke, North Stradbroke and Moreton islands.

Over time these have become stabilised by vegetation and have isolated the bay to help support a relatively sheltered and shallow environment.

“Without the barrier islands, this stretch of coast would be very different,” Rodger says. “It’s hard to know where the coastline would be, sediment would be exposed to greater wave energy and there would be no seagrass or mangroves, which would influence the species that live there.”

Artificial reefs saving species

Between 1963 and 1984 a cluster of ships was scuttled by the Queensland government to provide safe anchorage for recreational boat owners on Moreton Bay’s sheltered eastern side. These are the Tangalooma Wrecks.

Currents carrying the larvae of marine invertebrates have since established them as artificial reefs attracting more than 100 fish species. They’re also visited by turtles, dugongs, cormorants and other large charismatic marine species, turning these wrecks into tourist attractions, particularly popular for snorkelling and scuba diving.

In other areas of Moreton Bay, the Queensland Department of Environment and Science has created artificial reefs to meet the needs of recreational fishers and reduce fishing impacts on natural reefs.

The first was deployed in 2008, and there are now eight established as part of the Moreton Bay Artificial Reef Program.

“We have created a variety of reef types over the years to sustain a broad diversity of marine life including fish,” says Steve Hoseck, a marine ranger with the department. “They are designed to benefit a range of different fishers, including spearfishers, line fishers, charter fishers, and some of our more recent reefs also benefit scuba divers.”

The reefs are constructed from a range of materials and have been named to reflect their purpose and design – reef balls, fish caves, fish boxes and apollo habitat modules. The design required for a site is defined by surrounding physical parameters because each reef needs to remain in place undisturbed long enough to allow time for the marine life to establish.

“Offshore, our reefs are more exposed to the elements and are made from really solid concrete structures that are stable and weigh anywhere from 16 to 20 tonnes,” Steve explains. The program has some units constructed from steel in deeper locations around Moreton Bay.

Different structure types attract different species, although it’s difficult to predict what structure type is going to attract what species. The modules are placed on sandy habitat, where there is no reef structure within 600m.

First the structure provides shelter for small fish, then benthic species such as coral, sponges and algae begin to settle and grow. Next come the species that feed on the benthic organism, and finally the larger predators arrive, helping to establish an artificial ecosystem.

The humpback dolphins of Moreton Bay

Dr Elizabeth Hawkins, founding director and lead researcher at Dolphin Research Australia, completed post-graduate research on dolphin behaviour, particularly communication, at Tangalooma in 2001.

These days she’s working on the Moreton Bay Dolphin Research Project, established in 2014 in partnership with the Queensland Department of Environment and Science. It identifies dolphins by using fin characteristics and after six consecutive seasons the team has identified 840 individual bottlenose dolphins and 178 humpback dolphins in Moreton Bay.

Australian humpback dolphins prefer inshore habitats in Moreton Bay. The western side, around the Brisbane River, is a key habitat for them. The turbid estuarine waters there support the species’ southernmost east coast population.

“The majority of our work is about observing the animals and their wild ways so we can really get an understanding of how they use this space, how they interact with each other and how that fits in to the whole population structure,” Elizabeth says. “We need long-term systematic surveys and comparative data so we can ensure their conservation and protection.”

Understanding the social world of humpback dolphins is in its infancy, but Elizabeth’s research has already found that males form paired alliances.

She is unable to say yet how the dolphins are coping with urban impacts but this will become clearer. What is known is that dolphins in Moreton Bay are under a great deal of pressure from a number of threats from human activity.

Animals are often harmed or killed by propeller and vessel strikes along with fishing gear entanglements.

“Preliminary research by colleagues has found that Australian humpback dolphins have relatively high loads of pollutants, which could be negatively impacting their reproductive systems,” Elizabeth says. “But how resilient these dolphins are to these threatening processes is currently unknown.”

The team has begun to collect and analyse biopsy samples to investigate the toxicology of the animals. Humpback dolphins are particularly susceptible because their habitat preference is based on community and learnt behaviour.

“They do not choose to avoid busy impacted areas such as the Port of Brisbane because this inshore area is actually an important habitat for them,” Elizabeth says.

Urban debris and turtles

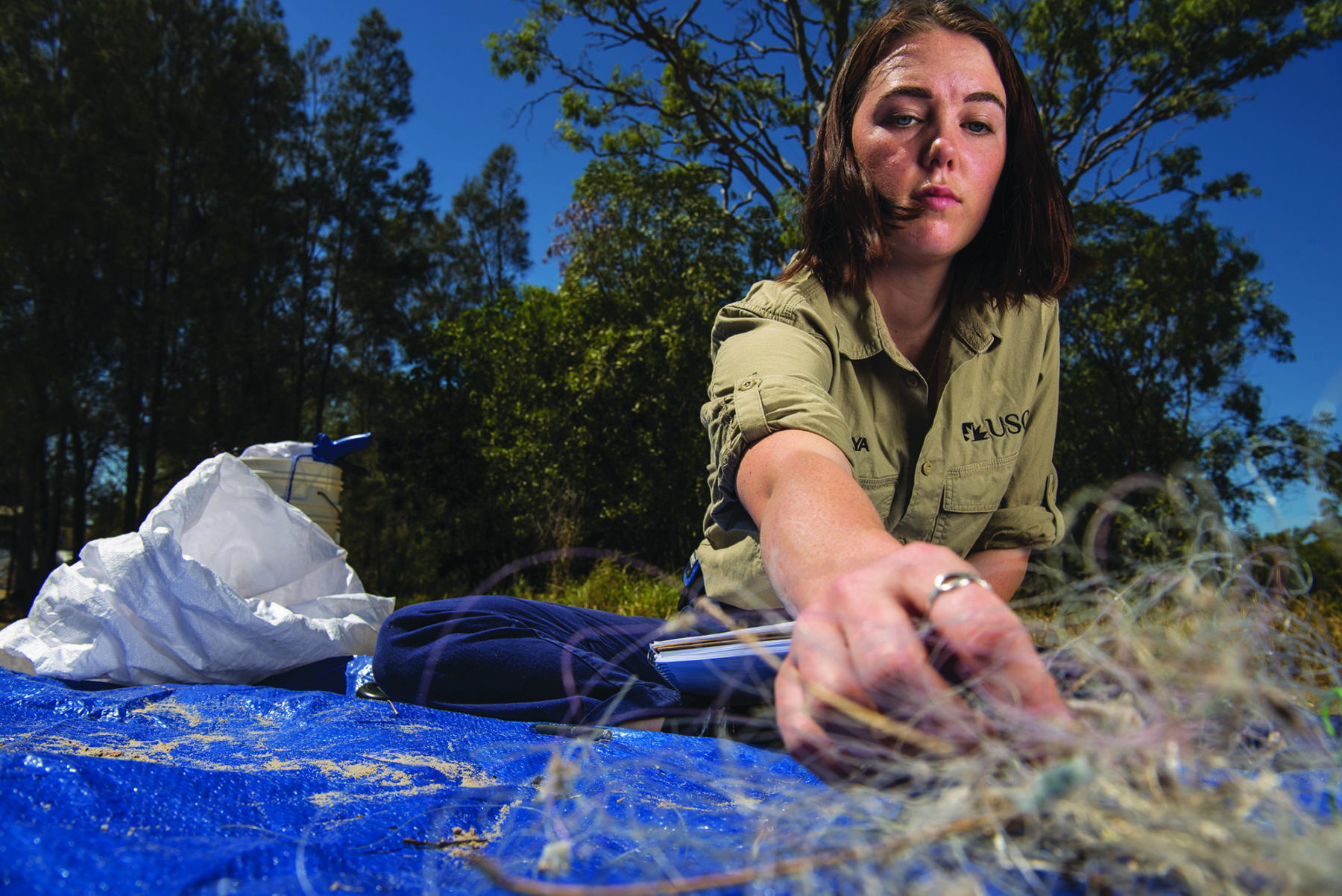

Moreton Bay is a critical feeding area for resident green and loggerhead turtles. Although some nesting has been documented here, it mostly occurs north of Bundaberg. Dr Kathy Townsend, a University of the Sunshine Coast animal ecology lecturer, is investigating how urban debris affects marine species such as sea turtles.

“I look inside a lot of different things that have stranded,” Kathy says, explaining that a necropsy is often needed to identify a cause of death. Strandings can include both living and dead animals.

Even when animals are alive and taken into care, stranding is still likely to cause death. The Queensland government’s Moreton Bay stranding database shows there has been an annual average of about 298 strandings for each of the past five years. The figures include dead, sick, injured, incapacitated, entangled or rescued marine turtles.

When Kathy began doing necropsies on sea turtles in 2006, 2 per cent of deaths were attributed to plastic ingestion. That statistic is now about 33 per cent. Kathy has also found marine debris in the guts of animals where the primary cause of death had been attributed to entanglement in fishing gear or boat strike.

In 2018 she co-authored a paper to clarify how many pieces of marine debris it takes to kill a sea turtle. Results from nearly 1000 turtle necropsies used in the study revealed it took just 14 pieces of plastic to kill in half the individuals examined, and that a single piece has a 21 per cent chance of causing death.

Kathy recalls removing an assortment of debris from the gut of one juvenile sea turtle: “We retrieved items like fishing net, twine, plastic bags, balloons…pieces of hard plastic, such as a takeaway container, lolly wrappers, bits of foam from a meat tray – normal consumer stuff you find on the beach and use day to day.”

Her team is now working on a global analysis to identify locations where sea turtles have a higher chance of interacting with marine debris. “We’re trying to identify sources of debris, how it moves from the land to the ocean, and how it travels on the currents,” Kathy says.

It’s hoped this research will suggest ways to reduce the risk of interaction. Kathy says it might be most efficient to address stormwater issues in specific catchments, rather than all catchments, meaning local authorities can make the most of limited resources.

One of Kathy’s post-graduate students, Amalya Valle, is investigating seabird distribution in Moreton Bay and how these creatures interact with marine debris. She hopes the project will identify whether certain species are more susceptible to specific marine debris types and is also investigating the issue from a behavioural perspective.

By placing cameras on garbage bins, Amalya can see which species are foraging in them, how they’re getting inside, what material they’re targeting, and if there’s a bin type that reduces the risks.

Many computer-generated models operate under the assumption there is more rubbish where there are more people. Kathy and Amalya are investigating other factors such as local population demographics and the median wage and social structure of an area.

“You would think that a place like Moreton Bay, which is really close to Brisbane, would show strong signs of human impact,” Kathy says. “We are finding quite the opposite as people walk along their favourite beach and clean it up, which is really lovely, but it does make our job more challenging.”

Kathy applauds the fact that the region’s people seem to have a sense of pride about where they live, taking cleaning up into their own hands. It’s yet another reason why Moreton Bay deserves its new status as a Mission Blue Hope Spot.