How to survive a shark encounter

The thought of being bitten by a shark is terrifying. But, have you ever taken a moment to plan what you would do if this happened to you? After all, we think about and even practice evacuation plans for fires and other emergencies. Why not sharks? Natural disasters and accidents can never be fully avoided, but being prepared and knowing how to respond if they do happen can have significant impacts on both short and long-term results.

If you’re about to go for a swim or surf, not wanting to think about being bitten by a shark is understandable, and you certainly wouldn’t be alone in this mentality. While not specific to shark bites, anxiety has been directly linked to reduced preparedness for disaster situations, like floods and heatwaves. But taking steps to prepare yourself for adverse events not only reduces negative outcomes if they do occur, but can also protect you against associated mental health consequences following these events.

So, if you are a recreational water user, or even just like to walk along the beach, then pausing to put a plan together for this situation could prove to be a life-saving decision. If you find planning for shark bites intimidating and too difficult to think about, consider talking through it with like-minded friends. Community and social support can play a major role in disaster preparedness, mental health and well-being, and may even improve coordinated responses down the track.

Shark encounter management plans need to be personalised to match how you use the water. For example, a plan for a surfer would be different for someone diving. But there are of course some general rules.

Scenario 1: You are in the water and you see a shark coming towards you. What do you do?

Stay calm! Yes, this sounds outrageous given the circumstances. But remember that only a very small percentage of encounters with sharks actually end badly. By staying as calm as possible, you will be able to think more clearly and logically, and are more likely to make calculated decisions. This will also help you to avoid erratic movements and an elevated heartbeat, which may draw an otherwise uninterested shark to you. Discard anything that may be attracting the shark to you (e.g. if you have been spearfishing and are carrying your catch).

Many species of sharks rely on ambush predation, so keep the shark in view to the greatest extent possible. While not absolute, behaviours such as rapid rushes towards you, jerky or erratic swimming patterns, arching of the back, and fins angled downwards can indicate that the shark feels threatened or is likely to attack. If you feel unsafe or threatened by the shark, the best course of action is to get out of the water. This should be done in an urgent, but controlled manner.

If getting out of the water quickly isn’t an option, position yourself vertically, and up against something if possible: for example, a rock if you’re diving, or use your surfboard as a barrier if you’re surfing. This can help you to appear larger than you are, and thus potentially of less interest. More importantly, this also reduces the number of angles from which the shark can approach you. If you are with another person, come together and position yourselves back-to-back.

If possible, grab or hold onto something to use as a weapon against the shark. This could be a camera, a rock, your surfboard – if feasible. Shark skin is not only tough, it’s also very coarse. Using an object other than your body – whatever it may be – can protect your hands, provide added strength and durability, and keep your immediate self at a slight distance from the animal. Punching a shark in the snout, as is often recommended, will result in a great deal of damage to your hand and also puts your hand very close to the mouth.

If the shark comes in to bite, do whatever you can to defend yourself. If possible, try to target the most vulnerable parts of the animal: the eyes or gills.

Scenario 2: You have been bitten by a shark. What do you do now?

Again, try to stay calm and think rationally and constructively about how you can get yourself out of the situation. While this again sounds crazy, people who have survived these scenarios against all odds have reported feeling a sense of clarity in the moment that allowed them to devise a successful escape plan. Draw on what you know and your past experiences.

To survive a major shark bite trauma, three things must happen:

You need to get out of the water, quickly. Unless a bite is instantly (or almost instantly) fatal, stemming the blood loss is the most critical and urgent need. This is pretty much impossible while a person is still in the water. Use anything you can to help you get to the shore or boat as quickly as possible.

The bleeding must be stopped. Loss of blood is the most common cause of death following a shark bite, and depending on the severity and location of the bite, this can occur within a matter of minutes. There are a variety of strategies that can be employed, although most require assistance from first responders.

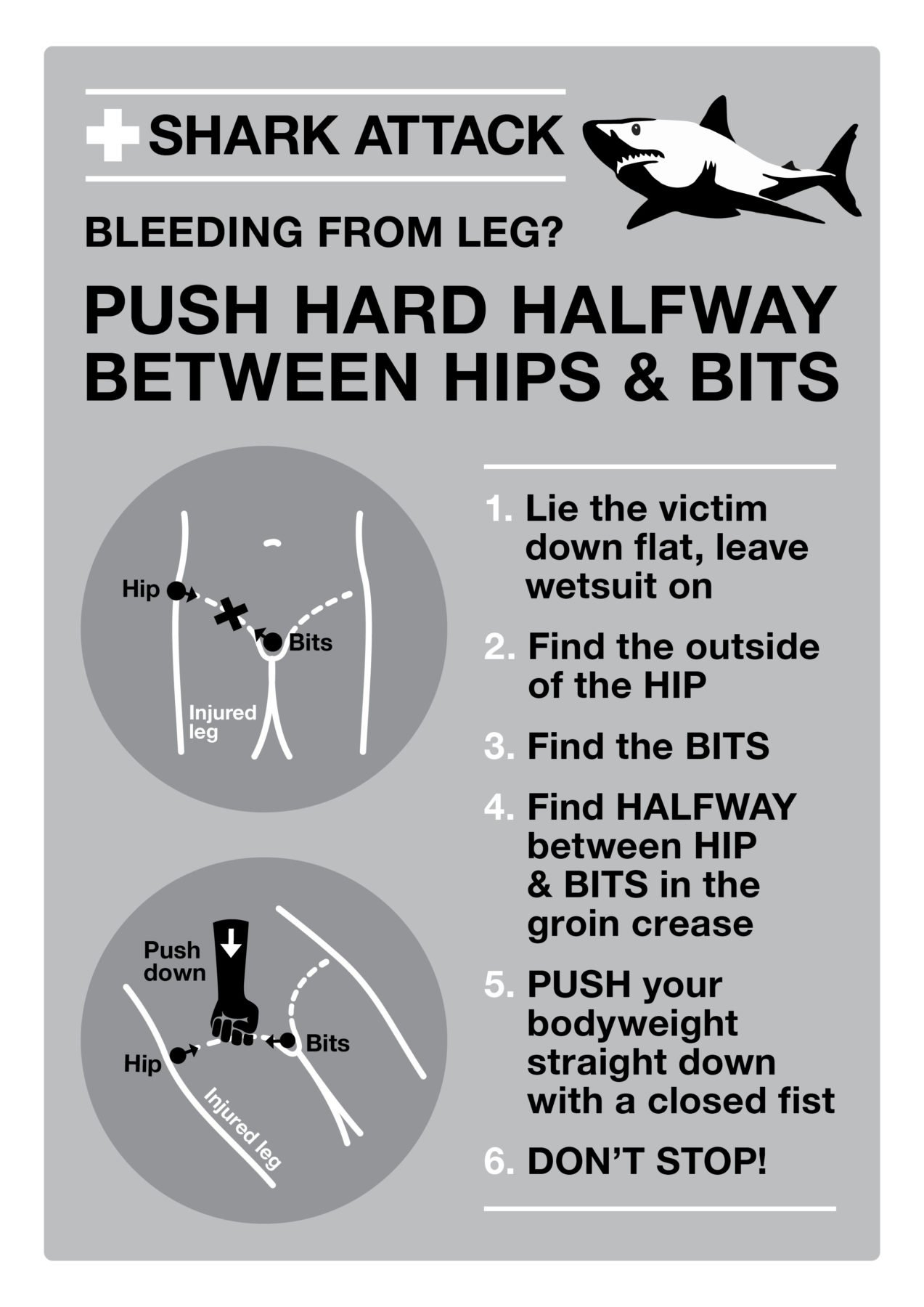

A recently published study by Nick Taylor and David Lamond from the Australian National University found that for bites to the legs (which is where the majority of major shark bites occur), applying pressure to the groin can be an extremely effective technique, and can be performed by just about anyone. Here’s what you do:

- Lie the victim down flat – if they’re wearing a wetsuit on, leave it on.

- Visualise an imaginary line between the outside of the hip and the genitals; basically follow the upper crease of the leg.

- Make a fist, keep your arm straight and push down using your entire body weight at a point in the middle of your imaginary line. Don’t stop!

Remember: To stop a major leg bleed, PUSH HARD, HALFWAY BETWEEN THE HIPS AND BITS.

Other measures commonly used by first responders to stem blood flow from shark bites are compression to the area (use a clean shirt or towel, if possible, to apply direct pressure), and fashioning a makeshift tourniquet from a surfboard leg rope, towel, shoelace or anything else that can be found. Although certainly better than nothing, these strategies are less effective.

As soon as possible, call for emergency help.

- You need to get to a hospital. Even if the bleeding can be stopped, specialised emergency treatment is essential and time-critical. Following blood loss and fluid management, antibiotic therapy to treat infection becomes the next critical factor to survival.

Dr Blake Chapman is an expert in shark-human interaction and the author of Shark Attack: Myths, Misunderstandings and Human Fear.