OPINION: Feral horses will rule a third of the Kosciuszko National Park under NSW government plan

The New South Wales government has released a draft plan to deal with feral horses roaming the fragile Kosciuszko National Park. While the plan offers some improvements, it remains seriously inadequate.

Feral horses trample endangered plant communities, destroy threatened species’ habitat and damage Aboriginal cultural heritage — all the while increasing in numbers. The draft plan would keep many horses in the national park, locking in ongoing environmental and cultural degradation.

The number of horses has grown dramatically in recent years under the Wild Horse Heritage Protection Act, which became law in 2018 and was championed by then NSW Deputy Premier John Barilaro. He and others argued the horses were important to Australia’s history of pioneering, pastoralism and horse trapping, and were related to rural legends and literary works.

But the cultural heritage of an introduced species should not override the needs of a highly vulnerable alpine environment. Barilaro quit politics this week – and with the driving political force behind feral horse protection now gone, we have an 11th-hour chance to safeguard this significant national park.

What’s in the draft plan?

On the positive side, the draft plan aims to:

remove feral horses from 21 per cent of the park

reduce feral horse numbers to 3,000 by 2027

prevent feral horses from invading new areas.

These are critical measures. As the draft plan notes, achieving them will need a set of carefully considered control methods, including ground shooting and putting down trapped horses.

Contrary to recent counter-productive management, reproductive-age females will no longer be released back into the park after being trapped.

But on the flip side, the plan will also:

allocate one third (32 per cent) of the national park to feral horses

maintain 3,000 horses within the protected area in perpetuity

attempt to control horse numbers without using the most humane and cost-effective method: aerial shooting.

Aerial shooting is ruled out because of fears around losing social licence to remove horses from the park. But this may make it impossible to achieve effective horse control across rocky, difficult-to-access terrain.

It also means feral horse control will drag out over years. This will result in larger numbers of horses being culled, compared with completing a cull within one year. Maintaining 3,000 feral horses in this reserve means accepting the removal of at least 1,000 animals every two years in perpetuity, based on a conservative rate of population growth.

Over 14,000 horses, and rising

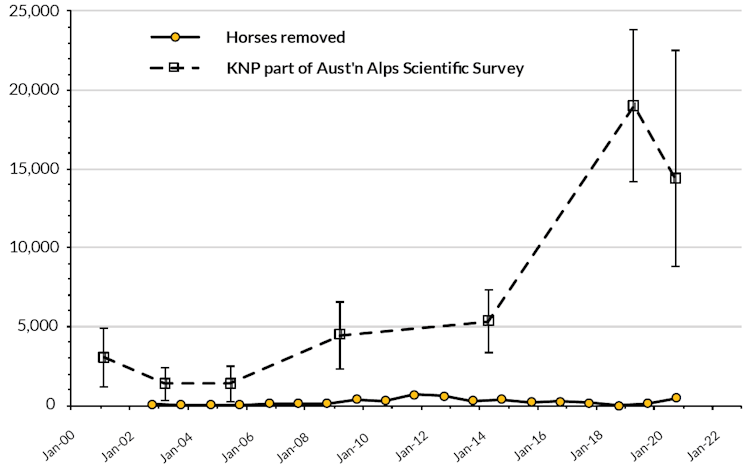

To understand the challenge, it’s important to understand the numbers. The chart below – using population data collected by ecologist Don Fletcher for a Reclaim Kosciuszko report – compares the number of feral horses in Kosciuszko National Park since 2000, with the number removed by trapping.

The number of horses in Kosciuszko was last measured in November 2020 at just over 14,000.

With an the ongoing rate of increase of 18 per cent per year and two years of population growth, numbers will have increased by 5,500. This means there’ll likely be almost 20,000 feral horses before control can start in 2022, under this plan.

Compare this with the 3,350 horses trapping has removed between 2008 and 2020, and it’s clear culling, including via aerial shooting, is urgently needed.

The huge, growing number of horses roaming Kosciuszko combined with the likelihood of immigration from outside the park, is also the main reason fertility control cannot work. The draft report is therefore right to reject fertility control as a workable solution.

33 threatened species in greater peril

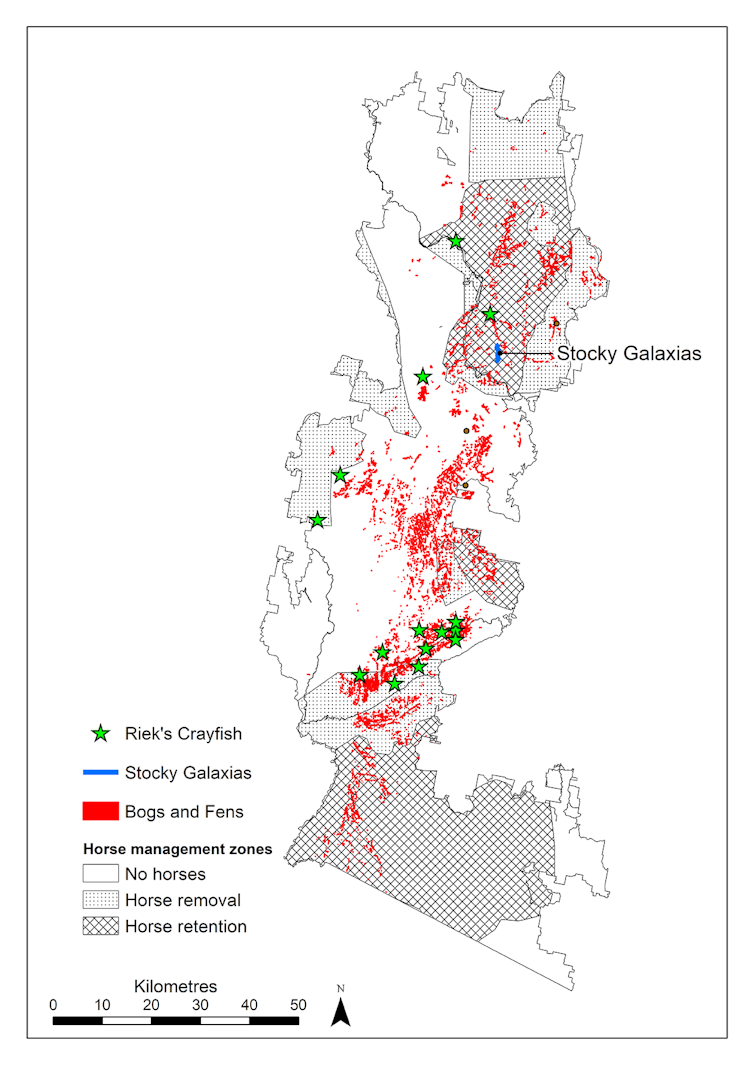

We are most concerned about the draft plan’s allocation of one third of the park to at least 3,000 feral horses, and likely many more given the limitations on control methods. These areas harbour important ecosystems and threatened species.

Using publicly accessible data from NSW Bionet and Atlas of Living Australia, we estimate at least 33 threatened species live within the horse retention zone. About half of these are either already known to be impacted by feral horses or we suggest will likely be impacted because they’re vulnerable to trampling, grazing or habitat damage.

For example, the only place the critically endangered stocky galaxias – Australia’s most alpine-adapted fish – occurs is within the horse-retention area.

This hardy fish was recently rescued from bushfires and faces grave risks associated with the Snowy 2.0 scheme. It’s currently protected from feral horses thanks to a stock-exclusion fence, and the draft plan notes fencing is only a short-term solution.

The endangered Riek’s crayfish also has a restricted range within Kosciuszko. If horses are removed in the southern part of the park, as the draft plan outlines, then damage to their habitat will decline by 2027. But horses remain a threat to their habitats in the north.

Alpine sphagnum bogs and associated fens are a nationally threatened plant community with a stronghold in Kosciuszko. It is particularly vulnerable to impacts from feral horses, and we calculate 28 per cent of its distribution in Kosciuszko will be inside the horse-retention zone.

Horses heritage value a non-sequitur

The draft plan’s main reason for keeping feral horses in the national park is to protect heritage values. However, the plan does not explain why heritage must be celebrated by keeping 3,000 feral horses in a national park.

In our view, while the horses have cultural heritage value to some, letting them continue to damage a fragile national park is an unacceptable trade-off.

Consider the recent Aboriginal cultural values report. It noted Indigenous Australians share similar heritage associations as skilled horse riders on farms since early colonial times. However, the report recommends acknowledging this heritage with information in a visitor centre.

Preservation of huts and interpretive signs are another way of acknowledging the heritage values of pastoralists past.

A social license

Research released this month surveyed 2,430 Australians and found 71 per cent accept that feral animals can be culled to protect threatened species. As the researchers write, this sentiment is not fully reflected in existing policy and legislation.

Barilaro’s exit may be an opportunity for NSW politicians to capitalise on this social licence.

This draft plan is one step towards protecting our native species, natural places and Indigenous heritage, and will be open for submissions until November 2.

But if aerial culling was also on the table, those goals could be achieved with fewer horses culled and at lower cost.

Don Driscoll, Professor in Terrestrial Ecology, Deakin University; David M Watson, Professor in Ecology, Charles Sturt University; Desley Whisson, Senior Lecturer in Wildlife and Conservation Biology, School of Life and Environmental Sciences, Deakin University, and Maggie J. Watson, Lecturer in Ornithology, Ecology, Conservation and Parasitology, Charles Sturt University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.