It was a baking mid-January day in 2019 and police officers were shadowing their suspect through Melbourne’s CBD. Moving carefully to avoid detection, the officers watched as smuggler Jeng Chiang made his way to his hostel in the city, where he’d been living after he entered Australia on a visitor’s visa in late 2018. After waiting a few moments for Chiang to clear the foyer and go to his room, the officers descended on the hostel and arrested the 28-year-old man.

Inside Chiang’s shared dorm room, the officers found rolls of duct tape and aluminium foil, disassembled rice cookers and deep fryers, and empty mailing boxes with shipping slips indicating they were destined for Hong Kong. It was enough to connect Chiang to six suspicious packages already intercepted by the Victorian Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning (DELWP) before they left the country. It wasn’t narcotics or firearms that Chiang was attempting to smuggle, but reptiles.

Chiang was the first suspect arrested as part of Operation Sheffield, a joint partnership between DELWP, Australian Border Force, the Department of Environment and Energy, Australia Post and RSPCA Victoria. The 15-month investigation exposed a chain of wildlife smuggling that stretched from the suburbs of west Melbourne to outback Western Australia, resulting in four convictions and the seizure of hundreds of live native reptiles destined for markets in Europe, North America and Asia.

“Chiang was pretty much the means to an end for the black market,” says Glenn Sharp, the DELWP senior wildlife officer who led Operation Sheffield. “He was acting like a mule, using encrypted conversations on WeChat to meet certain people who would hand over the animals to him.”

Chiang’s job was to conceal the reptiles in packages and mail them overseas. Instead he served a six-month prison sentence, after which he received a one-way deportation ticket back to his native Taiwan.

A lucrative trade

Australia has almost 900 native reptile species, of which more than 90 per cent exist nowhere else. Their unusual colourings, behaviours and genetic traits, the result of many millennia of evolution separated from the rest of the world, have made them highly valued on the international pet market.

Each year, hundreds of native reptiles – including blue-tongue lizards, water dragons and red-bellied black snakes – are smuggled by mail to overseas markets. According to data from the Australian Department of Agriculture, Water and Environment (DAWE), almost 90 per cent of all animals seized by authorities between 2018 and 2019 were reptiles. Authorities and conservationists agree the real number of animals being traded is likely to be much higher than what is currently being detected.

Australian law makes it illegal to export live native animals, except in very limited circumstances. But most species receive little legal protection once they’re taken overseas, with reptiles being traded openly at pet conventions, in online forums or in private groups on social media. One of the most heavily trafficked species is the shingleback lizard – also known as the bobtail and the pinecone lizard. It can sell for thousands of dollars overseas, with sub-species from WA fetching higher prices thanks to their distinctive colour patterns.

According to Dr Sarah Heinrich, a research fellow specialising in wildlife trafficking at the University of Adelaide, the constant push for novelty is one of the main drivers of the trade. “People are always looking for something different, whether it’s a new colour, genetic trait, or even if it’s a new species,” Sarah says. “It’s never going to be enough, and they are going to look for new ways to obtain those lizards.”

Although it’s possible to breed some reptile species in captivity, this isn’t always successful or financially viable, meaning that pet traders need to resort to catching reptiles in the wild. Customers may even express a preference for wild-caught pets, Sarah says.

Matthew Swan, wildlife compliance coordinator at the WA Department of Biodiversity, Conservation and Attractions, says overseas cartels lure young people such as Jeng Chiang to be couriers, offering all-expenses paid trips to Australia for the purpose of ‘poaching tourism’.

After arriving in Australia, Matthew says, couriers will either gather reptiles themselves using information from the internet or collect them from the cartel’s Australian poaching partners. Because of the ease with which they can blend in as tourists, accessible sites such as Rottnest Island, offshore from Perth, have become popular targets for poachers.

In extreme cases, poachers have broken into the homes of legal local reptile owners and stolen their pets.

“More organised traffickers will hire fully self-contained campervans and disappear into the desert. They’ll already have a shopping list of reptiles they want to find, and will go to a particular place to find a particular animal,” Matthew says. The landscape’s vastness means detection is impossible, allowing traffickers free rein in what one former poacher described as a “candy store”, where they can indiscriminately collect any reptiles without fear of being caught. “If they come across a snake while looking for a shingleback, it’s like finding a thousand dollars lying on the ground. They’re not going to walk past it,” Matthew adds.

Gasping for air

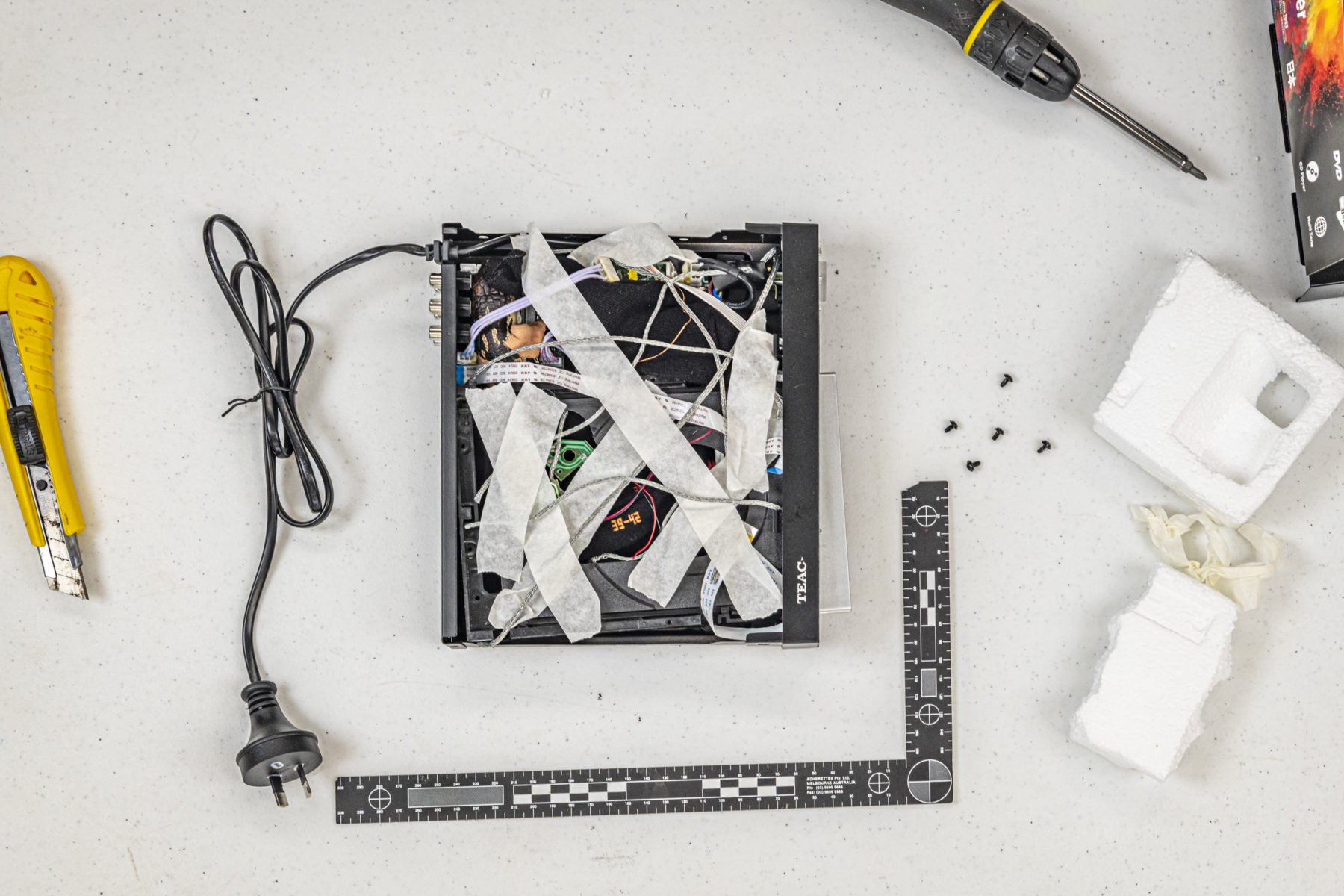

Once the reptiles are taken from the wild, traffickers will go to great lengths to conceal their cargo when shipping the animals in the mail, Glenn Sharp explains. Techniques can vary, but a common method is followed. To limit movement, the reptiles first have their limbs bound to their bodies using tape. They’re then put in a sock and placed inside a package, which could be a DVD player, rice cooker, shoe or toy. Up to two or three blue-tongue lizards could share the space inside one DVD player. To avoid detection from X-ray scanners, traffickers might create false compartments in the bottom of rice cookers or cloak the animals in a dense layer of play dough.

Sadly, reptiles are ideally suited for smuggling. Trapped for days without access to air, water or food, they’ll enter a torpor-like state called brumation. This allows some to survive their horrific ordeal, but most won’t. The high price of a shingleback lizard overseas means only a few need to survive for trafficking efforts to be worth the risk. When consignments are intercepted by authorities, it’s the confronting job of wildlife officers to open these macabre packages.

“Smaller reptiles like thick-tailed geckos have extremely soft skin,” says Kate Gavens, chief conservation regulator at DELWP. “Forest and wildlife officers and veterinarians must be very careful when removing tape to avoid damage to toes, limbs, or bits of skin. Some species will also drop their tails as a defence mechanism.” Kate adds that unbinding seized reptiles can be a painstakingly slow process, and the longer it takes, the more stressed an animal can become. After being assessed by a vet, some reptiles are treated and eventually rehomed, but others must be euthanised.

“After we’ve assessed those animals, we will do everything we can in our power to get them back to the wild, but the likelihood of that happening is very low,” says Matthew Swan, who oversees wildlife compliance teams in Perth. He says this is because authorities often won’t know where an individual reptile has been taken from, and attempts to place them in an unfamiliar environment can cause great distress or exposure to predators.

Furthermore, relocated reptiles could harbour diseases that pose a threat to local wildlife and ecosystems. Dr Leanne Wicker, Zoos Victoria wildlife health and welfare adviser, says a highly contagious reptilian coronavirus known as shingleback flu is a particular concern. The virus first emerged among shingleback lizards in the 1990s and is now reportedly widespread in WA. One study found almost 60 per cent of shinglebacks at two wildlife centres in Perth were infected with the virus, which can cause respiratory symptoms akin to the human flu. Without treatment, the mortality rate is high.

There is no evidence the virus can be transmitted to humans, but exotic animals found in the wildlife trade have historically played a role in the spread in humans of zoonotic diseases such as rabies and Lyme disease.

“We are really just learning about infectious diseases in reptiles,” Leanne says. “The movement of lizards around Australia in both the legal and illegal trade in reptiles poses a really significant risk to the health of Australia’s reptiles. One of the most concerning things is that it’s highly likely there are many more significant infectious diseases that we haven’t even identified yet.”

Breaking the chain

International border closures and restrictions imposed during the COVID pandemic have impacted global mail delivery services, likely reducing the volume of reptiles being exported from Australia.

Undeterred, traffickers have been using the downtime to turn their efforts to breeding and stockpiling animals in anticipation of when global restrictions begin to ease, according to a senior spokesperson from DAWE.

At the same time, authorities are investing in new and advanced detection technologies. In early 2020, the Australian government installed at airports and postal facilities world-first 3D X-ray scanning units that use machine learning to detect wildlife.

At the University of Technology Sydney, innovative scientists are prototyping an ‘electronic nose’ that can find smuggled wildlife by detecting their odour signature.

To bolster international enforcement efforts, DAWE will apply to have more than 125 species at high risk of trafficking added to the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora, a global treaty that regulates wildlife trade.

Even with a new arsenal of technology, the greatest challenge for authorities is stopping poachers in the wild. Kate Gavens of DELWP believes many Australians might be unaware of how prolific the trade is in Australia, or how they can help keep poaching in check.

Public awareness of the issue is slowly improving, with Crime Stoppers Victoria recording a 59 per cent increase in wildlife-crime related tips in the past year alone, but more can be done.

“Australians have a really critical role to play in helping us identify potential illegal trading,” Kate says. “For example, members of the public who are out in our forests might see people carrying egg cartons or nets, which is valuable information to pass on to Crime Stoppers.”

Another way to report suspicious activity is using Wildlife Witness, a free smartphone app developed by Taronga Zoo and wildlife trade monitoring network TRAFFIC. The app allows anyone to easily report suspicious wildlife trade activity by uploading a photo and pinning the location. “If you’re looking to buy a lizard or a snake as a pet, one of the key things is to make sure that the person you’re buying it from is licensed and can show you proof of a licence,” Kate advises. She recommends also looking at the overall condition of the animal, with signs of lethargy or ticks indicating the animal could have come from the wild.

Matthew Swan agrees: “The people at the top of the wildlife trade do not care about the welfare of the animals; they are only interested in the dollars at the end of the day. Please go to a reputable source for your reptiles because there are people out there who will rip you off.”

AUSTRALIA’S MOST WANTED BIRDS

Due to their colourful feathers and personalities, Australia’s native birds have become a lucrative target for wildlife poachers.

Rainbow lorikeet

With bright red beaks and colourful feathers, the rainbow lorikeet is one of Australia’s most-loved – and noisy – parrots. These birds prefer to nest in the suburbs, close to humans, because artificial lighting helps them spot predators. This also makes them easy for poachers to find.

Eclectus parrot

The eclectus parrot is one of the larger parrot species in Australia, with males coloured green and blue, while females have red and blue plumage. They’re mostly found in far north Queensland, feasting on berries and trees along Cape York Peninsula. The eclectus parrot is popular with pet owners thanks to its vivid colourings, high intelligence and talking ability.

Sulphur-crested cockatoo

Screeching flocks of sulphur- crested cockatoos, which descend on trees en masse to strip off seeds, leaves and small branches, are a familiar sight in Australia. The cockatoo has become a popular pet overseas thanks to its cheeky and intelligent personality, as well as its vibrant yellow mohawk. Trafficking has seen cockatoos introduced to habitats outside their native range in countries such as New Zealand and Indonesia.

Eastern rosella

The eastern rosella is another brightly coloured parrot, typically found in grassy forests in south-eastern Australia and Tasmania. A breeding pair can produce up to nine eggs, which wildlife traffickers can collect and smuggle out of the country. Eggs collected from the wild are hatched and then sold into the pet trade with little risk of detection.