There was great excitement on board CSIRO’s RV Investigator. “I found you a handfish,” Dr Candice Untiedt told Carlie Devine as they scanned images of the sea floor captured by the ship’s deep-sea camera. Carlie, a research technician, and Candice, a marine ecologist, both with CSIRO, were working on the Investigator when Candice spotted the strange fish. “I was sitting right next to her,” Carlie says. “It was so exciting because I’d said, ‘We’ve got to find one’, and there it was, just sitting on the bottom.”

Sitting on the bottom is what handfish do. Unlike most fish, they don’t have a swim bladder to regulate their buoyancy and so don’t often swim, although they can dart short distances. Instead, these fish walk along the sea floor, using their hand-shaped fins to move about and eating small crustaceans, worms and molluscs as they go.

Red handfish (Thymichthys politus) habitat has been devastated by native, but overabundant, short-spined sea urchins.

While obviously a handfish, the identity of the species Candice and Carlie saw remains a mystery. It looked most like a narrowbody handfish, collected only twice in scientific trawls, in 1984 and 1996. But it was bigger. “The narrowbody specimens are both about 5.5cm long, whereas the one we found was probably more than 10cm,” Carlie explains. “We don’t know how big the narrowbody species gets, so we don’t actually have a lot of information to go on.” It could even be a new species.

That’s one of the problems with handfish. Although some species live in shallow estuaries, some occur in deeper coastal waters and very little is known about them. “Several species are only known from one or two specimens collected in deep water and haven’t been seen for many years,” says University of Tasmania (UTAS) researcher Dr Jemina Stuart-Smith, who, like Carlie, is a member of the Handfish Conservation Project and National Handfish Recovery Team (NHRT).

Only found in southern Australia

Handfish are found only in southern Australia, where 14 species are distributed around the mainland coast and Tasmania. It’s thought one – the smooth handfish – may be extinct. Three are critically endangered – the red, spotted and Ziebell’s. In July 2023, when Candice and Carlie saw ‘their’ handfish, RV Investigator was north-east of Flinders Island in Bass Strait, conducting the South-East Australian Marine Ecosystem Survey (SEA-MES). Fishery and ecosystem surveys were last carried out in that region 25 years ago. No more handfish were seen on the SEA-MES voyage, though it wasn’t for want of trying. “I looked at more than 90,000 images and saw in excess of 60 different fish species,” Carlie says.

Handfish conservation efforts are necessarily focused on the better-known threatened species. “The recovery team’s efforts are focused on all three critically endangered species,” Jemina says. But there hasn’t been a confirmed Ziebell’s handfish sighting since 2005, limiting our efforts for that species.”

The little that marine scientists know about the critically endangered red handfish is not good. Once found on shallow rocky reefs throughout south-eastern Tasmania, wild populations of this species are now confined to just two reefs. “Population numbers are so incredibly low, just 100 adults remain,” Jemina says. “That’s why we’re prioritising this species in particular.”

Red handfish reef habitat has been decimated by overabundant short-spined sea urchins. These native grazers chomp through kelp, leaving empty habitat in their wake that provides no shelter or egg-laying sites for the defenceless handfish. In a balanced ecosystem, predators such as rock lobsters would keep the urchins in check, but fishing has reduced their numbers.

Heat is another factor. In December 2023 the federal government authorised the temporary relocation of up to 25 red handfish to captive breeding facilities, to protect them from the anticipated marine heatwaves during the summer months. Their natural habitat will then be assessed to gauge if the fish can be safely returned after the danger has passed.

In August 2020 Jemina and her colleagues collaborated with the Tasmanian Commercial Divers Association to remove nearly 17,000 short-spined urchins from red handfish reefs.

“But this is a short-term solution,” Jemina says. “Long term, we’re hoping to restore ecosystem balance so that urchin numbers are controlled naturally. Our greatest challenge will be keeping rock lobsters in these areas. These sites will need to be protected – or at least protected from fishing.”

Assisted breeding

Meanwhile, a captive breeding and release program at UTAS Institute for Marine and Antarctic Studies (IMAS) aims to bolster the tiny red handfish population. “Dr Andrew Trotter and his aquaculture team have 103 handfish in their care,” Jemina says. “That’s more than remain in the wild. We hope to release some of these fish later in the year.” The spotted handfish is in a similarly dire situation.

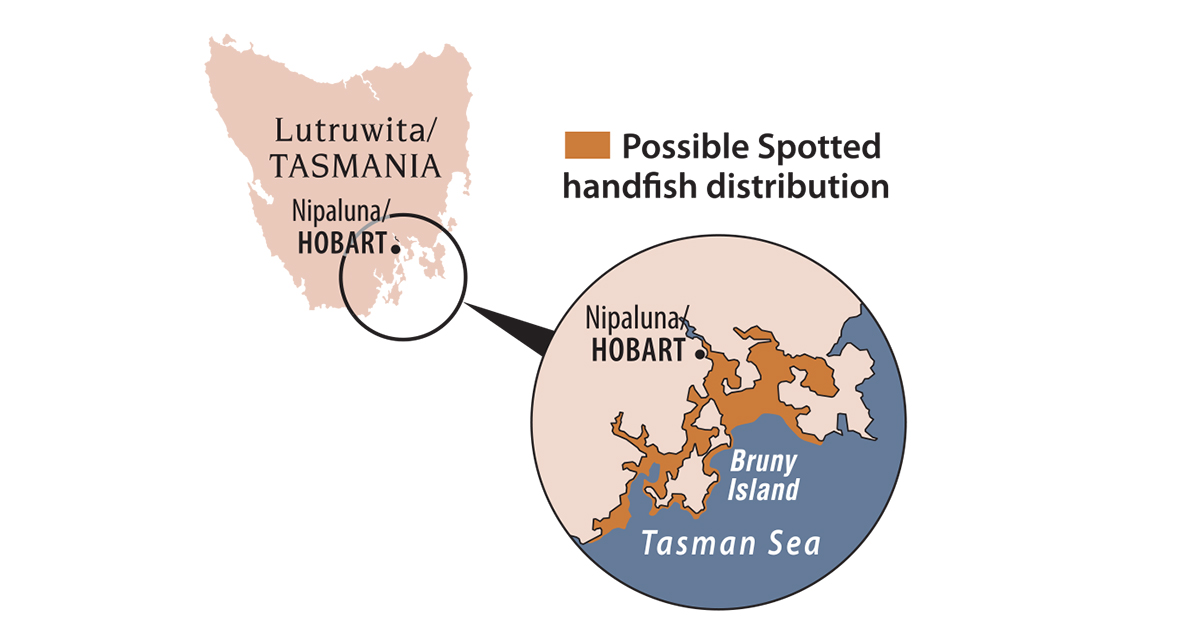

It’s thought there are less than 3000 remaining in the wild. “They used to be very easy to find in the River Derwent estuary,” says Carlie, whose work includes monitoring spotted handfish populations. “Now there are only nine or 10 isolated populations there.”

Spotted handfish live on the estuary’s sandy bottom, where sea squirts provide convenient stalks for them to wrap their egg clusters around. There, the eggs are attended by their protective mother. “She tends them, and cleans them with her mouth and hands,” Carlie says, describing underwater footage of a spotted handfish mum guarding her eggs. “It’s pretty amazing to watch.”

Spotted handfish sashay across the sea floor, walking on hand-shaped pectoral fins.

Sadly, an attentive mother handfish is no match for a hungry Northern Pacific seastar. This aggressive predator is an established pest in the estuary. “The seastar likes to eat sea squirts,” Carlie explains. “With fewer sea squirts for handfish to wrap their eggs around, there’s less spawning activity.”

To replace the sea squirt stalks lost to the introduced seastar, CSIRO has trialled ceramic sticks as artificial spawning habitat. It turns out the sticks are prime real estate.

“When we jumped back in the water and went along the transects, we could see how many handfish had used these spawning poles,” Carlie says. “They have no problem with them – they love them.”

So much to learn

Unlike many fish, handfish don’t have a planktonic larval stage. “They hatch fully formed, only a few millimetres long,” Carlie says. In a partnership between researchers at Seahorse World Tasmania and the SEA LIFE Melbourne Aquarium, spotted handfish are being captive-bred and reared for a year or two to give them a good start in life. “We’ll keep them safe for their first couple of years. We’ll give them live food, which teaches them to forage and hunt, and replicate their natural environment, the temperature and the sandy bottom,” Carlie says. Hopefully, captive-bred youngsters can eventually be released into safe conditions in the wild. “That’s something we’re working on over the next couple of years.”

If you’d like to see a spotted handfish yourself, Seahorse World Tasmania and SEA LIFE Melbourne Aquarium have them on display. These ambassador fish, along with educational campaigns in schools and communities, are helping to raise awareness about handfish and the problems they face.

Wild populations of red handfish (Thymichthys politus) survive on just two rocky reefs in Tasmania.

“They’re becoming quite an icon,” says Tassie-based photographer and marine scientist Matt Testoni. “When I sell handfish photos at the markets, there’ll be young kids, probably in Year 1 or 2, who say, ‘Mum, it’s my favourite fish’, and the parents say, ‘Yeah, that’s a spotted handfish.’”

Far fewer people would recognise Ziebell’s handfish, which typically has a pale body with purplish patches and yellow-edged fins. Like the red handfish, Ziebell’s lives on rocky reefs. It was always hard to find but was occasionally seen around Tasman Peninsula and D’Entrecasteaux Channel in south-eastern Tasmania.

Since the last confirmed sighting, IMAS researchers, using remote and autonomous underwater vehicles, think they have found Ziebell’s handfish in deep offshore areas in marine parks to the south and south-west of Tasmania. But no-one has seen any in their former known haunts. Matt hopes to change that. With support from the Centre for Marine Socioecology, Matt is on a mission to find and film the elusive fish. Locating any remnant population is a vital step in identifying threats and conserving the species. “We know virtually nothing about Ziebell’s handfish,” Matt says. “Let’s go find one. Then we can start that process.”

Even less is known about several other handfish species. Of the 14 species, six are described as data deficient on the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. This is problematic for a group of fish with specialised habitat needs and poor dispersal abilities due to their lack of a planktonic larval stage. Whether there are particular threats to these species, no-one knows. “We can’t manage species or potential impacts without data,” Jemina says.

This brave mother spotted handfish (Brachionichthys hirsutus) guards the cluster of eggs she has laid around a sea squirt.

The NHRT hopes that cutting-edge environmental DNA (eDNA) techniques, which can identify minute fragments of a species’ DNA in water, will help locate new populations of handfish and recognise species seen on camera. Handfish markers with which to identify eDNA are still being developed, but soon this technique will be a useful tool for finding the cryptic fish. “We plan to analyse eDNA samples from the Investigator voyage and we should get a large range of fish sequences,” Carlie says. “Hopefully some of these match handfish.”

These secretive fishes face complex, interrelated threats, including pollution, predation, loss of habitat and warming water in their cool-water coastal regions. They’re sitting on the southern edge of the continent, with no similar habitat to move to as the weather warms. Let’s hope, that with a helping hand, there’s a future for these handsome fish.

Red handfish work is supported by funding from the Foundation for Australia’s Most Endangered species, federal government, and the University of Tasmania’s Institute for Marine and Antarctic Studies.