The race against Lorikeet Paralysis Syndrome

“It’s a race against time on all fronts here,” says wildlife vet Dr Tania Bishop.

Tania works on the front line of an escalating crisis effecting birdlife throughout south-eastern Queensland and north-eastern New South Wales – Lorikeet Paralysis Syndrome (LPS).

What is Lorikeet Paralysis Syndrome?

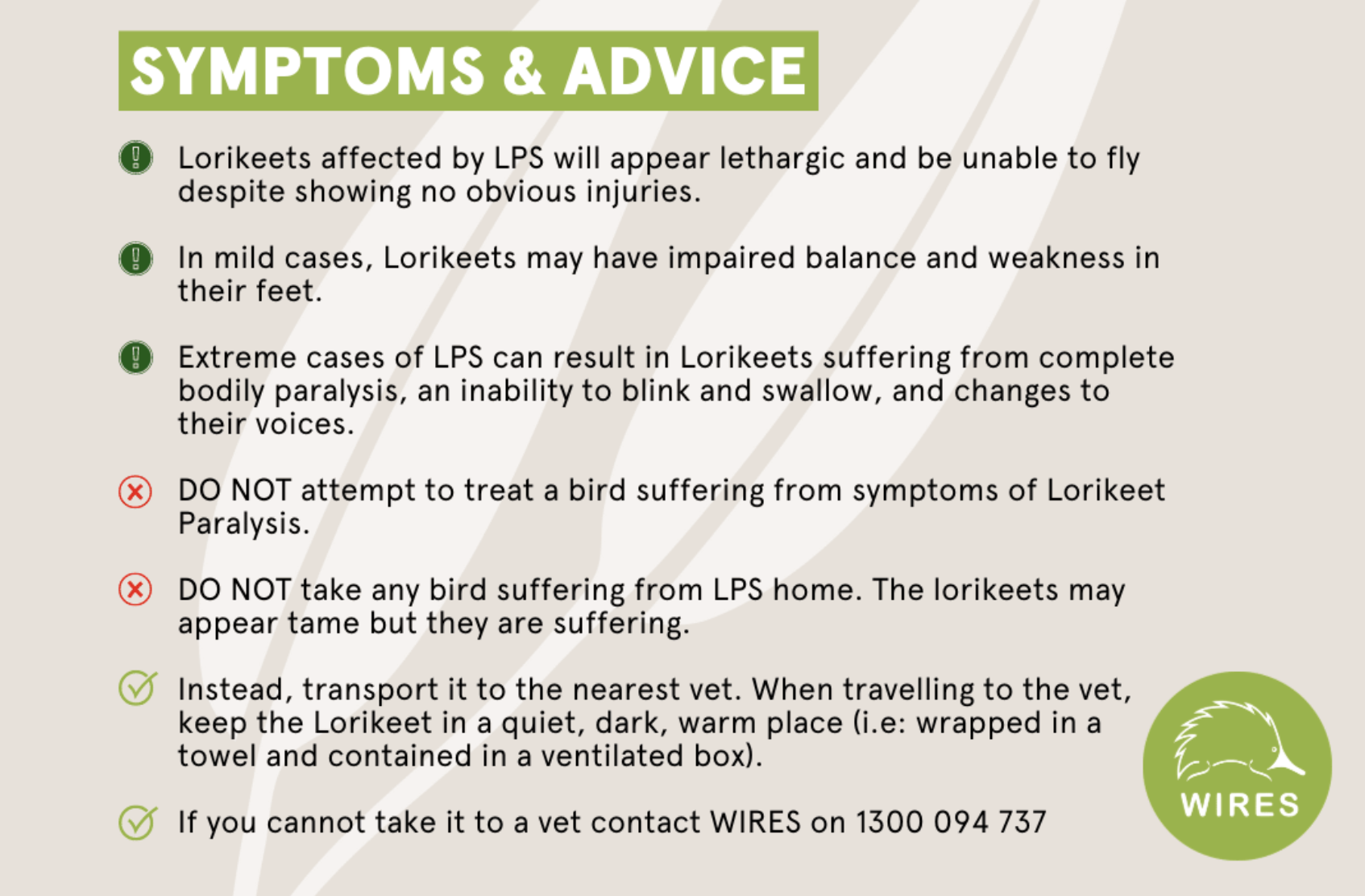

LPS primarily affects wild rainbow lorikeets (Trichoglossus moluccanus). Initially, afflicted birds lose balance and are unable to fly, despite not showing any apparent injuries. As the disease progresses, the birds lose control of their limbs – and their beaks – entirely.

How big is the problem?

The number of rainbow lorikeets becoming affected by LPS is increasing so dramatically that Wildlife Information, Rescue, and Education Service (WIRES) has now established an emergency response drop-in centre to cope with the influx of birds needing care.

Deployed to the centre – located in Grafton, in the northeast of NSW – are four WIRES emergency responders and three WIRES wildlife ambulances.

Tania is one of the specialist emergency responders working at the Grafton centre to triage and treat sick birds.

“LPS is a phenomenon that we’ve seen quite a few times over at least the last four years…but we’ve seen very big numbers of birds affected by it when we’ve had extreme rain events,” she says.

WIRES now estimates thousands of birds have now been affected by LPS in the region, but it’s not only the increasing number of birds with the condition that is worrying – cases are also becoming more acute.

“This time the birds seem to be more severely affected,” says Tania. “They go down more suddenly, they become paralysed more suddenly and need more immediate first aid and treatment.”

For many birds, LPS is fatal. And for the individuals that do survive, there’s a long road to recovery.

“Initially, the treatment is supplementation, support, lubrication of their eyes to make sure they don’t get damaged in this event, and making sure that they don’t aspirate [inhale food or water] because they can’t protect their airways properly,” says Tanya.

“And once we get them through the initial phase, the carers then have to very slowly take them through support, feeding them very, very carefully – going from electrolyte solutions and then gradually to food replacement solutions like nectar mix and things like that, until they can build them up and get them out into a cage where they can finally get their strength back and go back to the wild.”

Time is critical. The sooner an LPS-affected bird sees a vet, the better its chance of survival.

“The longer a bird is not flying, the longer it takes to get back that strength,” Tania says. “It’s like an athlete that’s off training for a couple of weeks.”

WIRES have been sharing the load with the EPA, Wildlife Health Australia, RSPCA, Vets Beyond Borders and private veterinary practices.

“We are extremely grateful to the concerned members of public bringing birds in for assessment, and to the local vet clinics for helping share the load. We couldn’t save them without the much appreciated assistance of the community,” says Tania.

What causes Lorikeet Paralysis Syndrome?

Various theories have emerged over recent years, including infection, but the most popular current theory is that LPS is caused by the ingestion of a toxin.

“It’s come down to us believing at this point the most likely thing is toxicosis – some substance causing a toxicity within these birds,” Tania says.

“We know that it’s something affecting their kidneys and their liver very severely, and then ultimately their musculoskeletal system.”

But identifying this toxin is the subject of ongoing research.

Scientists believe the toxin most likely forms on a plant and could be seasonal, or caused by extreme rain and heat events.

“So we’re looking at something like either a fungus or a bacteria at this stage,” Tania says. “Pending genetic testing and other research has ruled out countless suspected causes already, so we’re getting very close to discovering the cause in the current round of research from samples from this last event.”

How you can help

WIRES urges members of the public who encounter lorikeets showing suspected symptoms of LPS to follow these guidelines:

“The main thing to remember is these birds cannot swallow safely,” says Tania. “Trying to feed them yourself is actually very dangerous [for the bird].

“They are going to be desperate for food because they’re hungry, but they don’t have the ability to swallow and protect their airways properly.”