There is a reason wasps are the inspiration for so many sci-fi books and films – many species lay their eggs on, or in, the bodies of other arthropods so their larvae have a nutritious and safe start to life.

Nightmares aside, when most people hear the word wasp, they think of the problematic and invasive European wasp. But did you know there are more than 10,000 species of native wasps in Australia – wasp taxonomists are finding new species in backyards every year – and they have some of the most bizarre life histories of any animal.

Here’s a collection of some of our most fascinating native wasps:

Cuckoo wasp (Chrysididae)

In Australia, the cuckoo wasp comes in a variety of bright metallic blues and greens. Classed as a parasitoid, like many wasps, it lays eggs in the nests of mud-dauber wasps. The cuckoo wasp’s eggs hatch first and the larvae then eat all the stored food in the chamber. The cuckoo wasp has the impressive ability to roll into an armoured ball to protect itself if it is caught entering another wasp’s nest.

Gasteruption wasp (Gasteruptiidae)

The most elegant of insects, the female gasteruption wasp often has long ovipositors to insert an egg into the cell of solitary bee nests, so the larva can hatch and feed on the bee larvae and nest provisions. They are difficult to spot, with a unique – and almost invisible – way of flying, which makes them look like a piece of string floating in the air, leading to the common name of “ghost wasp”. They also have organs in their legs that act like ears. These organs help them to sense vibrations when waiting for bees to leave their nest. You may notice them hanging around the bee hotel in your backyard.

Velvet ant (Mutillidae)

The female velvet ant is flightless and resembles a furry ant. Once the female mates with the winged male, it spends the day searching for the underground nest of another wasp or bee to lay eggs. Because the female is vulnerable walking on the ground, it has a stridulating organ in its abdomen which produces a squeaking sound to help it deter predators. If that fails, the velvet ant has developed a very potent sting. North America has many large and colourful velvet ants, but we also have our fair share of beautiful species in Australia.

Thynnid wasp (Thynnidae)

This group of flower wasps has a fascinating life cycle. The wingless female releases a pheromone to attract a winged male. The male picks her up, mates, and then takes her to a nectar-oozing flower for one of the few meals in her short life. He then drops her back on the ground so she can find the larva of a scarab beetle on which to lay an egg. Many orchids in Australia have co-evolved to mimic the shape and pheromones of a female thynnid wasp in order to fool the male into pollinating them.

Reindeer wasp (Eucharitidae)

Believe it or not, its reindeer-like antennae are not the weirdest thing about this wasp. Once the wasp larva hatches on a leaf, it searches for a specific ant species to latch onto. Once attached, the ant will enter the nest where the wasp larva will drop off and feast upon the defenseless ant larvae before pupating and eventually emerging as an adult. They are able to avoid attacks by the host ants by mimicking the ants’ chemicals.

Australian hornet (Abispa ephippium)

Not actually a true hornet, this large potter wasp is a common sight across Australia, where it almost sounds like a miniature helicopter as it buzzes around. It forms a mud nest on buildings or other structures, where it captures the caterpillars of moths to feed its growing larvae. You may notice these, and other potter wasps, gathered around pools of water, where they collect mud to build their nests.

Giant spider wasp (Leptodialepis sp.)

Including the largest wasps in Australia, these beautiful insects attain a body length of almost 30mm. Once the female has dug a chamber, it finds and paralyses a large huntsman spider with a powerful sting and drags it back to the burrow. It lays an egg on the spider’s body and seals the chamber. The wasp larva slowly feeds on the spider, leaving its vital organs to last to ensure the spider doesn’t decompose before the larva is ready to pupate.

Perilampid wasp (Perilampidae)

This tiny “disco-ball” wasp takes things to a new level – it is a hyperparasitoid. The larva, known as planidia, enters the body of a parasitic larva of another wasp that is already present in a chamber of a host arthropod. Once the initial parasitic wasp larva has finished eating the host (usually a caterpillar) and is pupating, the perilampid wasp planidia exits the host wasp’s body and begins feeding on it, ending up as the last one standing in the chamber.

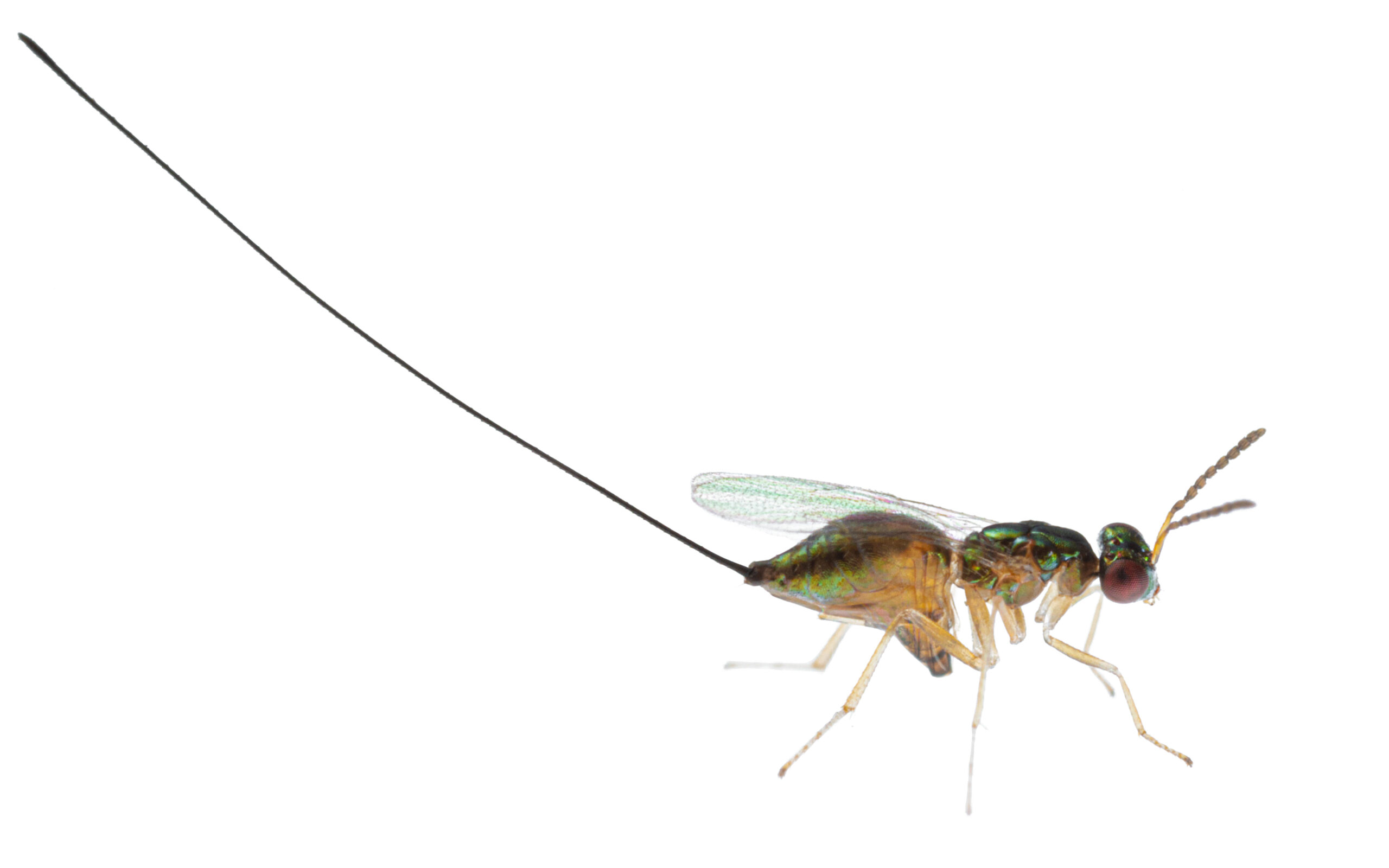

Torymus wasp (Torymidae)

This tiny, odd-looking wasp is part of the super-family Chalcidoidea. Its long ovipositor is used for inserting eggs into a variety of different hosts – other wasp nests, inside caterpillars or even fly larvae inside flower-heads. One species inserts its eggs into the galls (abnormal plant growths) on leaves, after which the larvae either feed on the plant material itself, or on the larvae of the insect that formed the gall. There are more than 50 species of these metallic coloured wasps in Australia and they can often be found feeding on native flowers.