Ashley Love is a bear of a man: tall and solid, with a mop of white-grey hair. He’s also the founding father of the proposed Great Koala National Park (GKNP), although eliciting information from him about the park is akin to spotting its namesake nestled in a tree during daylight – nigh on impossible.

By Ashley’s own admission, he is only one person in a colony of committed conservationists who have, for decades, been fighting for the koalas of the Mid North Coast of New South Wales.

“Local conservationists were campaigning to protect koala habitat back in the 1970s,” Ashley says. “But it’s taken 50 years of hard graft, and a recent change in classification of the koala – from vulnerable to endangered – to finally protect the most important koala habitat in the world.” In February 2022, under the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999, the iconic marsupial was classified as endangered on Australia’s east coast, with reports revealing up to 62 per cent of NSW’s population had been lost since 2001. Queensland’s population crashed by an estimated 50 per cent over the same period.

At the time of the classification, conservationists and scientists declared the endangered listing as an imperative turning point for koalas.

“Koalas have gone from no listing, to being listed as vulnerable, then endangered, within a decade,” said WWF-Australia conservation scientist Dr Stuart Blanch. “That is a shockingly fast decline. The decision [to list koalas as an endangered species] is welcome, but it won’t stop them from sliding towards extinction unless it’s accompanied by stronger laws and landholder incentives to protect their forest homes. Koala numbers have halved in the past 20 years… We must turn this trend around and instead double the number of east-coast koalas by 2050.” On the heels of this change in classification, and perhaps emboldened by it, NSW Labor campaigned for the GKNP in the lead-up to the March 2023 election, which they won. Shortly afterwards, the new government committed $80 million in funding over four years to support the park’s development.

“I don’t accept that one of our most loved and iconic native species could become extinct here,” said Premier Chris Minns. “By protecting the places these koalas live, and by working closely with all stakeholders, we can ensure we bring these incredible creatures back from the brink.”

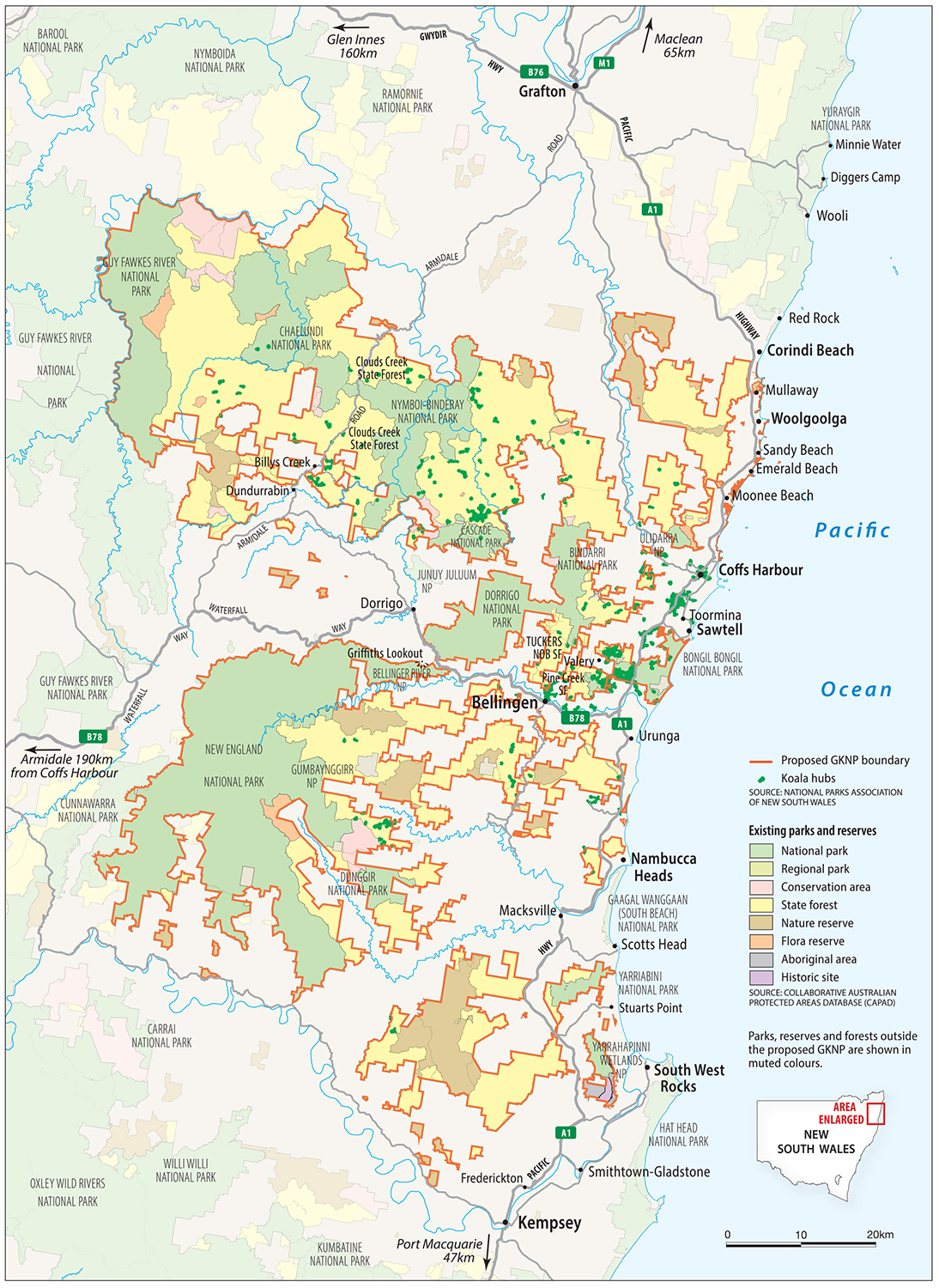

By June the government was being urged to fast-track the GKNP, with MPs and environmentalists alike saying state-owned logging operations continue to kill the endangered marsupials across land set down for the park. By September logging was stopped in 106 koala hubs – areas of important habitat identified by the NSW environment department in 2017. The hubs cover just 5 per cent of the state forest that the government is now assessing for potential protection. The reviews are expected to be complete by the final quarter of 2024.

While this was a much-welcomed first step, many believed it didn’t go nearly far enough and called for the government to impose a logging suspension across the entire area of the proposed park. “We need to stop logging the hubs and the compartments that surround them,” said National Parks Association NSW president Dr Grahame Douglas. “We need to stop logging all native forests within the GKNP.”

Ashley concurs. “Koalas don’t just live in isolated hubs. They move. They travel. We know that from the extensive survey work we’ve done. If you protect a hub, but decimate the surrounding forest compartment, you destroy the corridors that koalas, and a raft of native species, use to access other habitat and feed trees.”

As it stands today, the proposed park will include 1760sq.km of state forest and 1400sq.km of existing national parks across five LGAs – Clarence Valley, Coffs Harbour, Bellingen Shire, Nambucca Valley and Kempsey Shire. It will also be a world first – a dedicated koala national park – and will protect about 20 per cent of the state’s wild koala population, 44 per cent of its identified koala hubs and, according to Ashley, it is the best koala habitat in the world, bar none.

Koala land custodians

For years, Uncle Micklo Jarrett has been a fixture in the idyllic country town of Bellingen, a 35km drive south-west of Coffs Harbour.

With his long, dark dreadlocks and easy smile, he’s hard to miss, and his exuberant welcome sets him apart. “Giinagay. Yaam ngaya Gumbaynggirr ngulungginyay. Yaam nganyundi wajaarr,” he says. “That means welcome. I am a Gumbaynggirr Elder and this is my Country.”

Surrounded by state forest, national park and private landholdings, Bellingen is nestled in the heart of the GKNP. As a Traditional Owner and Elder, Uncle Micklo is keen to be part of the dialogue about the park. “The concept of a GKNP has been around for decades and I come to it as a custodian of the land to support it through my language and storylines, and thousands of generations of Dreaming,” he says. “It’s my job, it’s all Gumbaynggirr mob’s job, to let people know how important it is. Ngiambandi wajaarrbin yarrang jaagi gurraygu – our homelands are sacred to everyone.”

Uncle Micklo is particularly set on conserving koalas. “Dunggiirr [koalas] are sacred to my people and the landscape of the Gumbaynggirr Nation. They’re vital to our Creation stories, laws and customs, and the Gumbaynggirr identity.”

As well as this, dunggiirr are a widjir (totem) animal for Uncle Micklo. “When dunggiirr are dying it’s like part of my family is dying, you know. We need to help people understand that. We need to help people realise that looking after Country, protecting it, is everyone’s purpose and it will make us all strong.”

His point is reiterated by ecologist and tireless eco-warrior Mark Graham when I meet him at Clouds Creek State Forest, 90 minutes drive north-west of Bellingen, the following day. “It’s all Gumbaynggirr Country,” he says, as we gaze over the heavily wooded hills and gullies that roll east to the sea. “And it’s all a place of plenty, on a continental scale.”

Mark explains: “Australia is a place of waxing and waning resource availability, drought to flood, and Gumbaynggirr Country was traditionally seen as a place of last resort – where other nations’ people could come to survive. That’s because the mountains come right to the coast, so there’s always water and an abundance of food, from the forest through to the sea.

Our mission now is to protect, restore and expand the fabric of life here, to keep the rivers flowing, the rain falling, the forests intact and the animals thriving.”

Mark’s words hold great resonance because of what has been – bushfires ravaged the region from September to Christmas Eve in 2019 – and what is to come: the state-sanctioned logging of great swathes of Clouds Creek State Forest, home to a host of ancient Gondwana plant species, native hardwoods and endangered animals, including the koala, southern greater glider and glossy black-cockatoo.

A dedicated band of locals beat back the fires, and today this incredibly resilient community is standing together once more to fight a “scourge we deem to be just as destructive, the Forestry Corporation of NSW”.

I meet Barry Hunt and Rhona Verrall at the Clouds Creek blockade site, along the Armidale to Grafton road and aptly named Glider Reviver, where you can stop for a chat about the cause as well as a cuppa, a slice of cake, a bunch of freshly picked flowers and even some home-grown vegies. Since January 2024 the duo have turned up at 4am sharp to prevent loggers from entering the native forest and to protect endangered species. Despite the early starts, both are determined to hold strong.

“We’ve lived here for more than 20 years and over that time have seen logging practices change dramatically,” Barry says. “It used to be a small crew with chainsaws selectively logging, but now it’s massive machinery that rips and tears at the forest and decimates wildlife habitat. It’s apocalyptic and we can’t have it.”

As if on cue, a logging truck rolls past, hauling a huge, bright-yellow feller buncher – a heavy-duty vehicle with tracks that rotate like an excavator, allowing it to move through the forest while dropping and gathering trees.

Barry explains: “It has an arm with a chainsaw attachment. The arm grabs hold of the tree around the base, cuts it, then puts it in a pile. The number it can log in a day depends on the slope of the terrain and the density [of trees], but it’s in the hundreds.”

Gumbaynggirr Elder Aunty Alison Buchanan is grateful for conservation efforts at Clouds Creek State Forest, where protestors have blocked the passage of logging machinery since January 2024.

This is not the first time Clouds Creek has been blockaded. According to local activist Meredith Stanton, logging contractors came calling in the late 2000s, despite detailed reports highlighting the decline of koalas in the area during a 10-year period from 1998. “Then, as now, the harvest plans failed to provide adequate protection for koala habitat, so we must [provide it],” Meredith says, resolute. Clouds Creek, which sits within the boundary of the GKNP, is one of many government-owned native forests that are currently available to be harvested for hardwood. Vigilant locals continue to protest logging operations in other state forests within the proposed park and the NSW Environmental Protection Agency has been charged with ensuring that there is no increase in logging in the permitted areas to compensate for the halt to logging within the hubs.

“It’s profoundly distressing to me, to the Gumbaynggirr people, to our community, to realise that the government’s intention is to let loggers in and at some point down the track, maybe a year or 18 months from now, make some form of GKNP after these globally significant habitats have been gutted,” Mark says. “The koala is endangered and in steep decline. The reality is that all industrial logging needs to stop across the GKNP immediately.”

Forest for conservation

Dean Kearney is for the trees. He’s worked for the Forestry Corporation of NSW for more than 25 years, developing a deep understanding of the canopy and the life that lives beneath it.

As we stand in a slice of state forest north of Coffs Harbour, Dean explains the principles of multi-use forests, where sustainable timber production is just one objective.

“More than 80 per cent of the NSW public forest estate is permanently dedicated to conservation,” the Manager of Environment and Sustainability says. “And in state forests where timber harvesting is permitted, we also look after hundreds of public recreational areas, are charged with fire management, maintaining roads, tracks and trails, and we support local organisations with recreational and tourism businesses and forest regen[eration] projects. Our harvesting program involves just 1 per cent of state forests each year.”

While there is no dispute over the management of Forestry’s 20,000sq.km of ‘recreational’ forest when it comes to the GKNP, there is over its continued logging of native hardwoods within the proposed park. Dean won’t be drawn on this matter – “That’s a government policy issue so I can’t comment” – but is happy to walk me through the planning that precedes a harvest operation.

“We have an overarching strategic plan, which sets out our sustainable yield limits for the next 100 years, and tactical plans for the next 5–10 years. And on the ground, in a hardwood forest like this, we develop a detailed site plan that will take us anywhere up to one or two years to complete. It includes ecological and cultural surveys, as well as plans for where roads will be maintained and detailed maps of the area.”

I’m particularly interested in the survey work, which, Dean explains, include broad-area habitat searches, acoustic wildlife monitoring and, most recently, thermal drone imaging to help better understand how wildlife populations respond to timber harvesting in state forests over time.

Whipping out an iPad, he pulls up a topographic map of the forest in which we stand. It’s overlaid with a confusing confection of colours, shapes, symbols and letters that, when zoomed in on and deciphered, show areas set down for tree felling and the survey work accompanying it. The map also includes areas where felling is excluded and individual trees have been identified to be retained, listed by type: “giant”, “dead standing”, “hollow bearing”, “glossy black-cockatoo feed”, “nectar”, “koala browse” and others.

“This iPad-based electronic mapping is crucial,” Dean says. “We have people out in the field for weeks at a time, undertaking surveys, gathering data on wildlife, identifying habitat trees and assessing forest use. It’s all recorded and used to inform our operations. When our contractors come into the forest to fell trees, they are required to use the same system and data so we can be sure they’re only taking trees that are suitable to be felled for timber and not those that are to be protected,” Dean says. “We conduct regular compliance checks to ensure it’s all being adhered to.”

According to the Environmental Defenders Office, however, “in the past three years alone, Forestry Corporation has been fined 12 times for illegal logging activities. There are 21 investigations still pending,” a spokesperson says.

“Forestry Corporation operates under bilateral agreements with the federal government, called ‘regional forest agreements’ (RFAs), which allow logging to bypass normal federal environmental scrutiny. No other industry benefits from such an allowance. Under the current system of RFAs, threatened species such as the koala, greater glider and gang-gang cockatoo are being driven to extinction and the ecosystems and landscapes that we depend on are being destroyed at an astounding rate.”

Iconic koala habitat

Data recording on an iPad may not feature in John Pile and Anne Coyle’s forest surveys, but they’re exhaustive nonetheless.

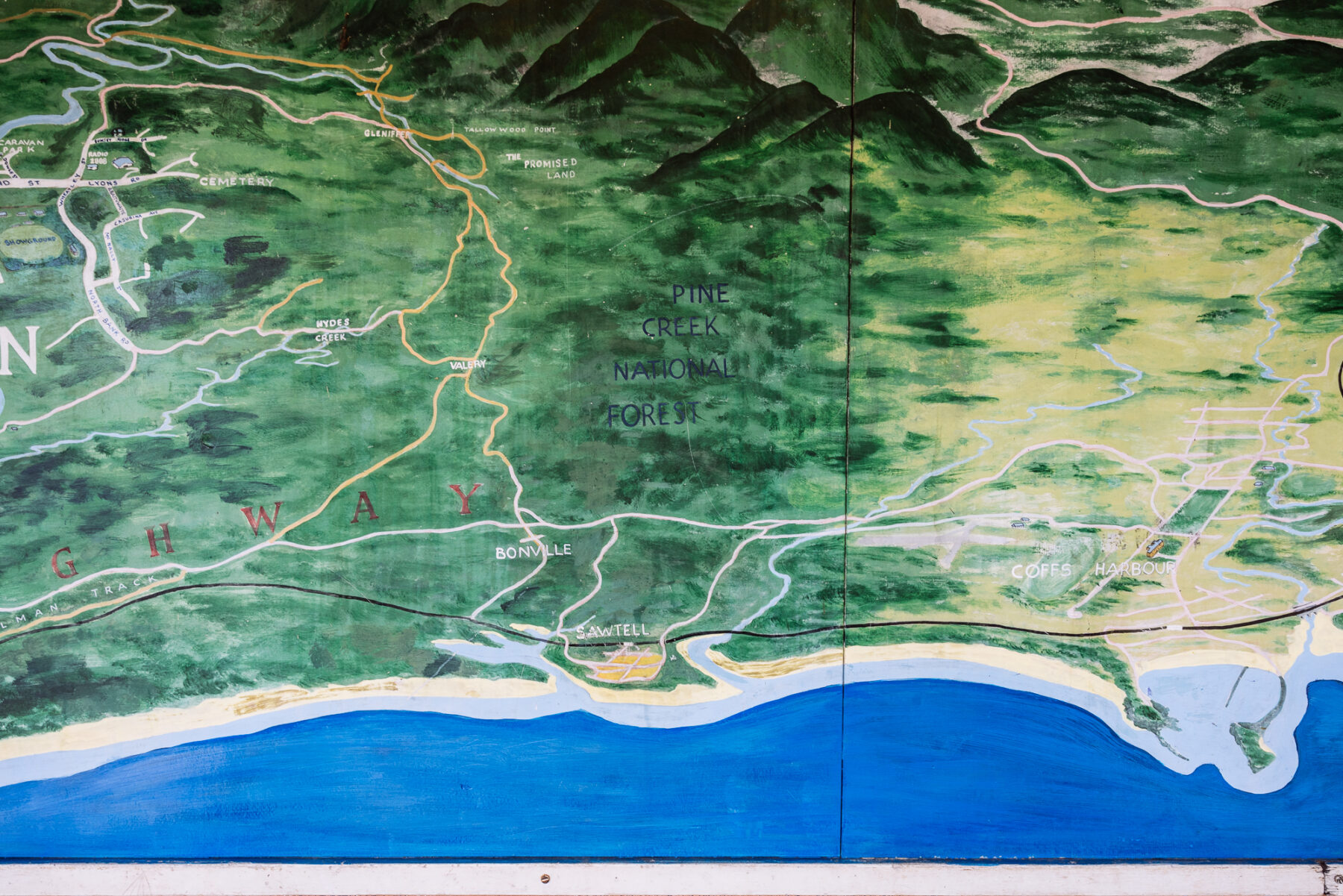

Many moons ago the couple bought an over-worked patch of land in Valery, just south of Coffs Harbour, and have spent the ensuing years regenerating it. Today, it’s a green haven where frogs, birds, possums, pademelons, koalas and all manner of other native wildlife find refuge.

Beyond its boundary lies Pine Creek State Forest. Earmarked for inclusion in the GKNP, it is widely recognised as the most iconic coastal koala habitat in the world.

As I wander among old-growth tallowwood, brushbox, pink bloodwood, ringwood and flooded gum with a barefoot John on a mizzly Monday, John talks about the logging that has occurred here in the past 30 years.

“Integrated logging began in the early 1990s,” he says. “It’s the tool used to turn the last of these diverse, moist coastal forests into simple plantation forests [blackbutt]. It reduces biodiversity, dries out the forest and creates a young, even-aged forest that poses an incredible fire risk. Despite our protest to Forestry Corporation NSW at the time, it continued. And we weren’t alone in our protests, with some saw loggers siding with us, stating, ‘Until the conservationists strengthened their attack, there seemed no way of protecting other species.’”

Thanks in no small part to John and Anne’s tireless work to protect the forest, Pine Creek has also been the focus of three major independent scientific studies on koalas over the same three decades.

The latest, published by renowned wildlife ecologist and environmental scientist Dr Andrew Smith in December 2023, and co-authored by John, says: “The area supports a mosaic of wet and dry sclerophyll forest and rainforest on undulating topography across a network of moist drainage lines, which provides a high level of protection against intense fire and drought, enabling this region to support one of the largest and most stable koala populations in NSW.

“These findings indicate that the continuation and expansion of high-intensity logging across the remaining parts of the Pine Creek State Forest available for wood production has the potential to eliminate koalas from logged areas, destroy corridor links between remnant koala habitat in Bongil Bongil National Park and nearby upland conservation areas, and reduce the quality and integrity of koala habitat in the surrounding region including the proposed Great Koala National Park.”

Pine Creek is also a critical fire refuge. It escaped the Black Summer bushfires of 2019–20, unlike great swathes of state forest, national park and private landholdings to the north, west and south of it. More than 10,000 koalas across NSW perished during the fires and hundreds of thousands of hectares of prime koala habitat was burnt. It affected more than a third of the proposed park, and killed many hundreds – possibly thousands – of koalas within it. “Everyone loves koalas,” says Anne, “but won’t do what they need – protect their habitat from logging.”

Fighting fire with forest

Nurseryman Barry Hicks knows a thing or two about the 2019–20 fires. He lost everything. Well, almost. Incredibly, his sanity remained intact…and his caravan. “We called it an act of God,” he says, blue eyes twinkling. “It ate up everything in its path but left my van. Ran a circle around it. Can’t make any sense of how or why.”

The septuagenarian lives at Billys Creek on the western Dorrigo Plateau, surrounded by rainforest and native bush. He fought the fires for four months alongside his brother, whose shack is a stone’s throw to the north, and the locals of nearby Dundurrabin village. “I remember seeing a trail of smoke across the valley and thought, ‘Oh no, here we go.’ It didn’t ease up until Christmas Eve, when we finally had good rain. It was the first full night’s sleep we’d had since September.”

The devastation the fires wrought is writ large across the landscape – charred bones of homes and burnt-out banksia trunks – and in the battle scars the survivors have band-aided with nonstop recovery work. That work includes the nurture of thousands of rainforest and koala feed-tree seedlings in greenhouse tunnels at Barry’s now-rebuilt Blue Rock Nursery.

“I collect the seeds down in the gully,” he says. “I wouldn’t have believed it if I hadn’t seen it with my own eyes, but the rainforest down there pulled up the fires.”

Barry and I sit in his rebuilt shed (sans walls) chatting about this phenomenon with ecologist Mark Graham. “There’s been a huge body of work done into how and why rainforest retards fire,” Mark says. “The naturally high levels of moisture that give rainforests their name result in rapid breakdown of leaves once they fall from the canopy, so that these areas have much lower fuel loads and are moister than other forests.”

But surface fuels aren’t the whole story – there are shrubs and grasses that also contribute to fire behaviour. “The vegetation is quite dense, but much of the foliage often holds moisture, making them less likely to burn,” Mark continues.

Logging of adjacent native forest, however, creates greater fuel loads, which in turn pushes fire into these protected wet zones and attacks it. According to research by the Bushfire Recovery Project – a joint endeavour between Griffith University and the Australian National University in response to the 2019–20 fires – native forest logging increases the severity at which forests burn, beginning about

10 years after logging and continuing at elevated levels for 30-plus years. The project also found that the likelihood of “crown burn” (when the canopy is burnt) is about 10 per cent in old-growth forest versus 70 per cent in forest logged 15 years ago.

This drops steeply as the forest continues to age, but remains elevated for decades. This is because logging removes the canopy, resulting in increased drying of the young plants and soil by the sun and wind, and greater wind speeds on days with extreme fire danger. After logging, the young trees that begin to grow create an increased fuel load in the forest; many of those trees will die, becoming dry and highly flammable.

World-leading forest ecology expert Professor David Lindenmayer AO stated in the bushfire recovery report that the link between fire severity and logging had been found in global studies, such as in the USA and Patagonia, as well as locally in Australia.

“Logging typically takes only the trunk of the tree; the branches, the bark and the top of the tree are left dead in the forest. While some logging operations (mostly in Victoria) burn the forest after logging, up to 50 per cent of woody fuel can remain after the burn-off.”

Barry’s work with saplings, then, is fundamental to the recovery of the fire-ravished forests across the western plateau, as is his cultivation of koala feed trees, of which hundreds of thousands of acres were decimated (along with their inhabitants) during those darkest of months. “My life’s work is to regenerate the rainforest,” Barry says. “Like a wet blanket, it protects our forests and animals, the koala included, that call the bush around here home.”

Mapping koala hubs

When I meet Jack Nesbitt in the blue gum forest behind his family home in Brierfield, roughly 10km south of Bellingen, his English springer spaniel, Max, is running drills.

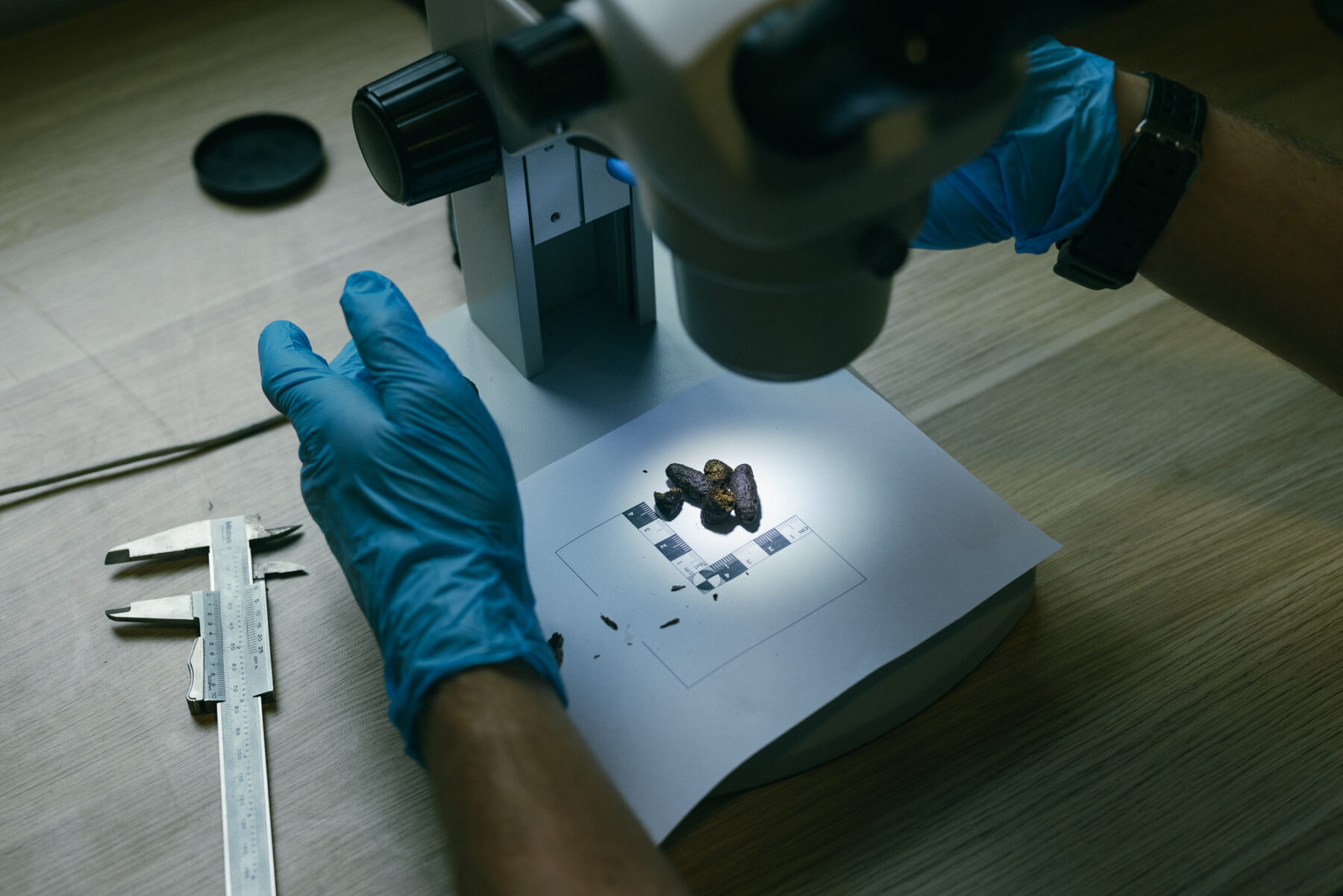

While thunderheads storm across the sky and industrial-sized mosquitoes make quick work of the thin layer of cotton protecting my legs, Max puts his nose to the ground, hunting for scats.

“He’s trained in koalas as well as two species of endangered antechinus: the silver-headed and black-tailed dusky,” Jack says, as the dog tracks left, then right, across the forest floor, back and forth, before pulling up at the base of a towering tree. He steps back and waits. “See how he’s not digging or pawing at the ground?” Jack says. “We don’t want him disturbing the site. We need the scats intact so we can send them to the lab for testing.”

Max is a conservation detection dog and a vital member of Canines for Wildlife, run by Jack, his father Brad Nesbitt and mother Lynn Baker, who are both long-time ecologists.

“We have four scent-detection dogs working on threatened species research, survey and management, as well as invasive species detection and control,” Brad says. “We work all the way up the coast and into south-east Queensland, and inland to New England.”

While Max waits, Jack collects a scat buried beneath leaf litter at the base of the eucalypt. “If this was a live hunt, we’d mark the position using GPS, note the time and date, take photos of the scat and any other identifiable koala signs [such as scratchings on the tree trunk], take it back to the office, label it and put it in the freezer [–20°C or below to slow degradation]. Then we’d send it off for analysis.”

At the lab, an array of testing is undertaken: DNA is extracted, which helps identify individual animals and their sex, and pathogen sampling for Chlamydia pecorum and koala retrovirus. It also provides insight into the overall population health and interrelatedness of groups of koalas.

This information, and Max’s work, Jack says, has been instrumental in helping map koala populations in hubs identified for inclusion in the GKNP. “Genetic analyses can be used to monitor populations over time and provide data on size, structure, diversity and health,” he says. “It also helps investigate movement. For instance, we collected scats from two small patches of remnant bushland in Toormina [a heavily urbanised area just south of Coffs Harbour] and found it was from the same koala.

Looking at the map, you have to wonder how it got from one patch to the other – it’s a bit of a mystery, did it hitch a ride in a car boot? – but goes to show how important backyard trees and wildlife corridors are. While they’re mostly sedentary and stay in one spot, when they need to, these guys can travel.”

Meet Mr Koala Head

It’s a steamy Sunday afternoon in Bellingen as the rally gets underway. Posters pasted around town have invited people to join a march across Lavenders Bridge in support of the GKNP. It’s the first of two for March, with more planned for the months beyond. The mood is upbeat as I walk alongside a tall, lean fellow wearing an oversized koala head. We stop for a group photo – handmade banners, gum leaves and toy koalas raised on high – before making our way to a grassy spot on the northern side. Seeking respite from the heat, kids stream in and out of the Bellinger River while others swing from a rope thrown over a tree branch.

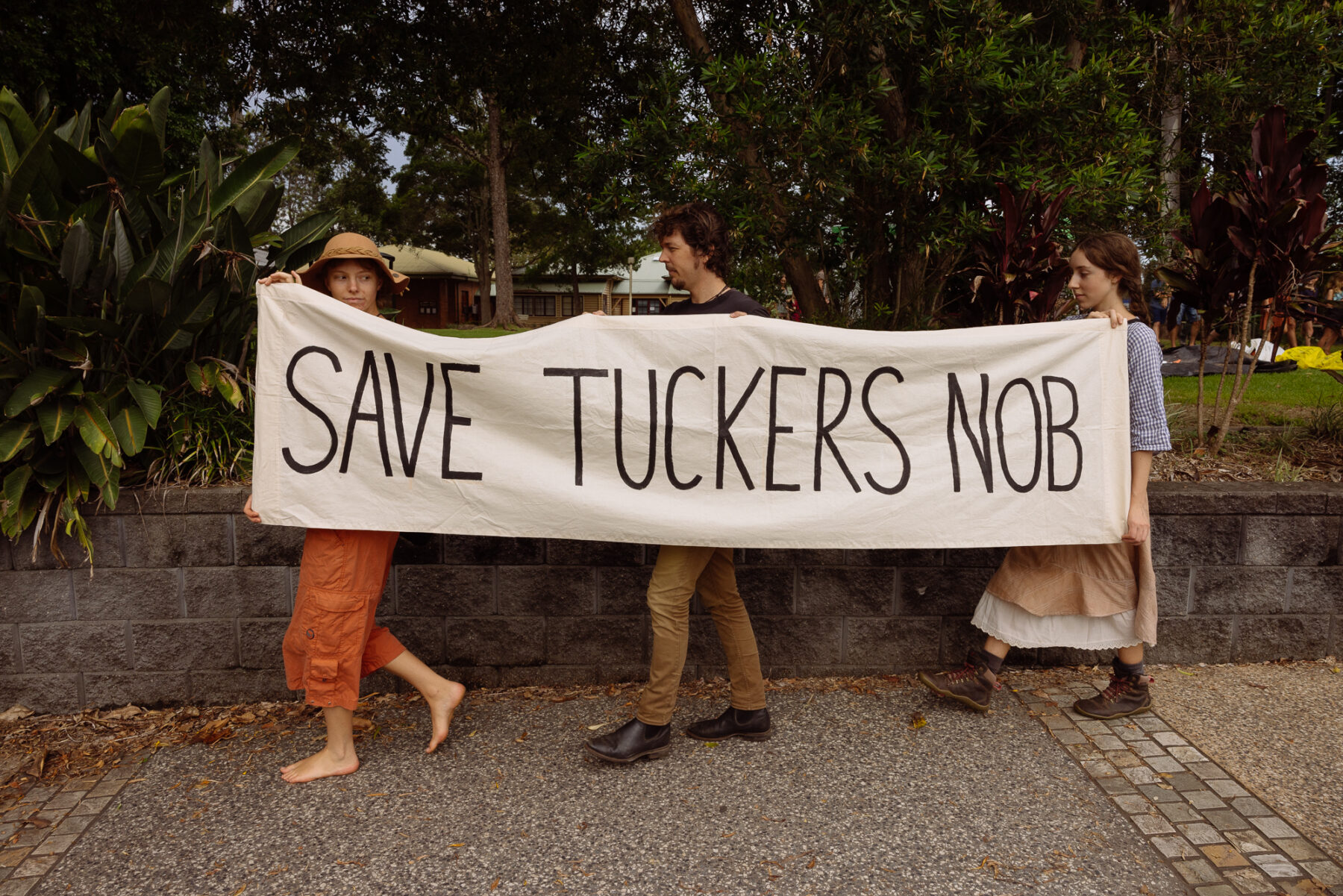

Mr Koala Head steps up to the microphone, removes his ‘hat’ and introduces himself. “For those of you who don’t know me, I’m Dr Tim Cadman. I live within the footprint of the proposed park and I, like all of you, have had enough of the carnage.” A respected environmental researcher and academic at Queensland’s Griffith University, Tim is referring to the current clear-fell plantation logging in Tuckers Nob State Forest. A few clicks north of town, it’s also set down for inclusion in the GKNP. “It’s a visionary idea, a national park for koalas,” he continues. “But logging and koalas do not mix. In fact, clear-felling is like a nuclear bomb for wildlife – nothing survives.”

I’d driven past the site on my way into Bellingen today and was confronted by the scene. Where once stood a thriving forest now lies a ravaged landscape. Broken limbs, exposed earth, burnt trees.

“If the proposed park is to live up to the ‘Great’ in its name, it has to be as big and as well connected as possible. The government has to end its take within the proposed GKNP area. It needs to stop the killing fields.”

They’re potent words, and as I look around, I see everyone nodding in agreement. They remind me of something the park’s founding father, Ashley Love, told me a week ago: “We have the best koala habitat in the world right here, on our doorstep. We must do everything we can to protect it. The time is now.”

Amen, Ashley. Amen.