Rising above a tall karri eucalypt forest, the granite domes of Western Australia’s Porongurup Range National Park sit ancient and heavy with time. They’re part of a landscape left over from 500 million years ago, when two-thirds of the world’s continents were huddled together and covered in lush rainforests on the supercontinent called Gondwana. The breakup of Gondwana had a widespread drying effect on most of the Australian landscape, but not here. The high elevation of the Porongurup peaks attracts a steady supply of rainfall, which is why a karri forest prevails here, about 500km east of where it otherwise would.

Beneath the trees, in moist banks of karri loam, little holes the size of five and 10 cent pieces dot the path that winds around the boulders and trees to the peaks. Each is a circular turret decorated with karri leaves, flower petals, sticks and grass to blend in with the forest floor. These are the homes of the Porongurup trapdoor (Cataxia sp.), a shy brown spider that grows to about 4cm long, with a dark body and light brown legs. The Porongurup trapdoors are charming architects in this wet forest landscape, building silk sheaths into the soft earth about 40cm deep and capping each with an open turret decorated to match the surrounding leaf litter.

There’s another kind of burrow here – a simple hole in the ground with some tell-tale signs of web near the opening. This is used by Proshermacha trapdoor spiders, affectionately nicknamed “proshies”, which are larger black arachnids that live alongside the Cataxia. Both these burrow-dwelling spiders are mygalomorphs: members of an ancient lineage that have retained biological similarities to the ancestors of spiders that first appear in the fossil record. They are the cousins of funnel-webs and tarantulas and, like them, are time travellers from Gondwana, surviving in moist, humid pockets in a world that’s changed around them.

Ancient burrowers

Trapdoor spiders are well known for their burrows with skilfully camouflaged doors. These entrances are attached by a silken hinge to an underground tunnel that can reach as deep as a metre for some species. Trapdoors are sit-and-wait, opportunistic predators, so these burrows are essential for them to feed, avoid being eaten themselves, and for escaping other threats such as fire.

Trapdoors have remained largely unchanged since first evolving about 400 million years ago. Unlike their more modern cousins, including the redback and the wolf spider, they’ve retained large downward facing fangs, two pairs of book lungs, and a thick hairy body well suited to burrowing and digging rather than weaving webs or running through the undergrowth.

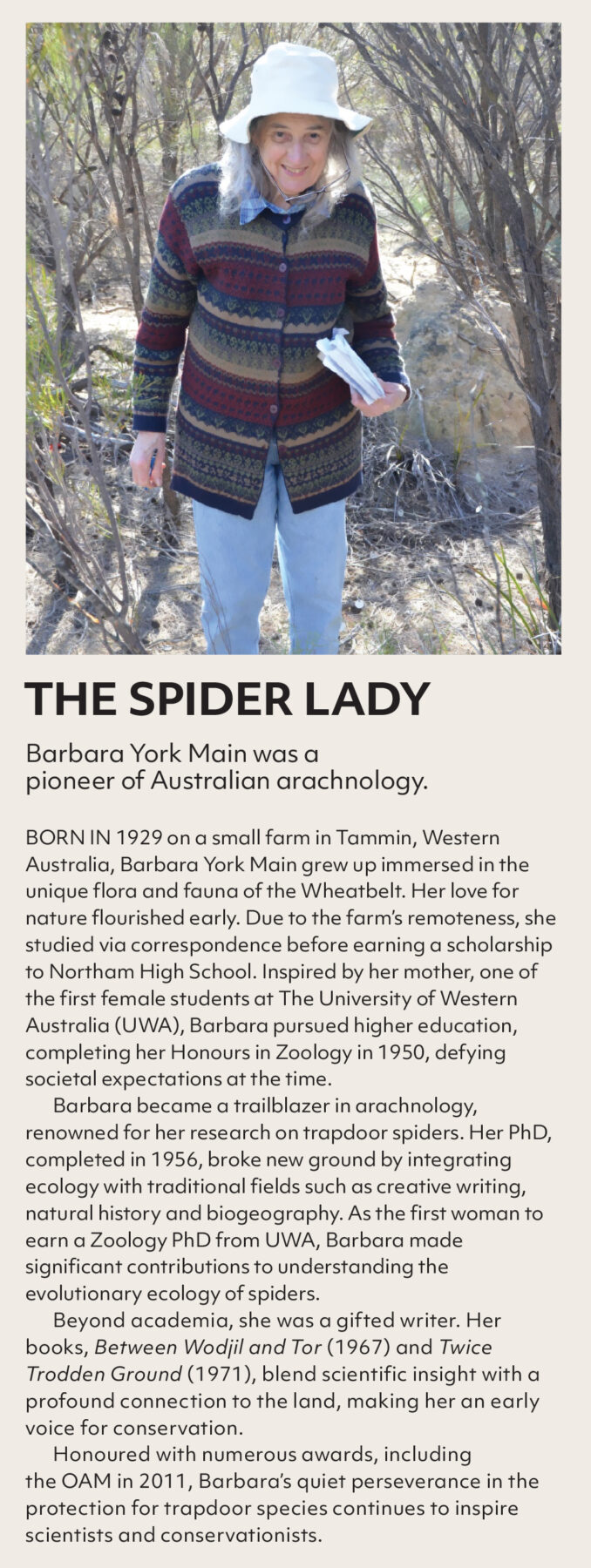

The Cataxia and Proshermacha genera of trapdoor spiders, unlike many of their close kin, do not have lids to their burrows. The elevation and cool climate of the Porongurups may mean they don’t need a lid to maintain their burrow’s humidity. The Cataxia were first described in 1985 by pioneering spider biologist Professor Barbara York Main (see right).

Due to Barbara’s ground-breaking work, trapdoor spiders came to be known as short-range endemics (SREs) – species with extremely limited geographic ranges, often confined to small, isolated, and/or highly specialised habitats. These species have often evolved fascinating life histories, adapting their biology, ecology and physiology to survive in very specific environments. As the quintessential SREs, trapdoor spiders are very important to conservation efforts as surrogates for other species with similar traits because individuals are easy to monitor long-term.

Trapdoor spiders will not move locations unless disturbed because they rely heavily on their burrows for survival. This makes them vulnerable, but also easy to keep track of because individuals will also not take over other burrows. Thanks to Barbara, we also know that individual trapdoor spider females can live for 43 years! Trapdoor spiders lay claim to being the oldest recorded living spiders in the world that we know of.

A rescue plan takes shape

In early 2023, a sign went up in the national park announcing construction to improve its trails, and we saw on the map that a new bitumen path would run right through an important trapdoor colony. We contacted the local national parks authority, WA’s Department of Biodiversity, Conservation and Attractions (DBCA), which explained the path upgrade was to improve accessibility to the toilets and to ‘Tree-in-a-rock’, a giant karri tree growing out of a granite boulder.

The original path was a dirt hiking trail, and the two species of trapdoor spider, the brown Cataxia and the black Proshermacha, both built burrows right up to and onto it. The path was rugged and dotted all along with rocks and tree roots, which made the toilets and Tree-in-a-rock tourist attraction largely inaccessible to wheelchairs and prams. The proposal was to seal 150m of the hiking trail with a bitumen walkway, connecting the carpark to the toilets and to Tree-in-a-rock. Cass did a sketchbook count of the spiders along the path of construction and documented 180 burrows of the two species that could be confidently identified.

The bitumen path meant that some burrows would be sealed indefinitely, starving the spiders underneath. DBCA was aware of the spiders, and that the Cataxia in particular were only known to live in the Porongurup Range, itself only 26sq.km. Though restricted, the spiders didn’t qualify for protection under existing environmental laws: they were classed as ‘locally abundant’, because colonies of this species exist at two other locations in the Porongurup Range, and the loss of some of the Cataxia trapdoors was not considered a danger to the survival of the species as a whole. DBCA had inquired with environmental consultants who’d confirmed this, and the construction was greenlit.

Although under-researched, the shy brown Cataxia trapdoors, like other trapdoor spiders, are likely to have a lifespan measured in decades. Some of the bigger burrows that dotted the path could house a spider more than 20 years old. In the Noongar language, trapdoor spiders are known as walbungkara, and our Elders share that plants and animals are our relatives and we must care for them like they are family.

Cataxia burrows are clustered in generational groups where a matriarch may be surrounded by multiple generations of offspring of varying ages. Our concern was that the scientific approach of viewing the Cataxia trapdoors as a species block erased the significance of the lives of the spiders who’d lived there along the path to Tree-in-a-rock for decades.

Mentored by the late Barbara, Leanda is a practising trapdoor spider conservation ecologist and has expertise in safely digging up and moving trapdoors. We connected with the Friends of Porongurup Range, a group of locals, and others who monitor the park, advocating for its health and wellbeing. They got behind us and supported us to mount an effort to rescue any spiders we could before construction began. We both live in Perth, four hours from the Porongurups, and Loxley Fedec, an invertebrates expert who has a trapdoor species named after her, was our local liaison and biggest cheerleader. Through conversations with DBCA, we were given permission to run a pilot program to relocate five spiders living in the proposed construction zone.

The relocation begins

To prepare for relocation of the spiders, we needed to use the right tools and techniques to safely remove them from their burrows without causing harm. This required careful observation of their microhabitats, particularly the leaf litter depth and soil preferences for burrow construction. All SREs are typically specialist species, so we needed to document where they were found as well as where they were not, to identify any limitations. Our first relocation was an important test, and we successfully moved Kenni (which means ‘one’ in Noongar), our first Cataxia spider.

The next challenge was determining an appropriate translocation site. It was crucial to find a new location with similar microhabitats, to ensure the specialist spiders could thrive once again. After scouting the area, we found the ideal location about 100m off the path and out of harm’s way. The pilot program included a translocation of five spiders from the proposed bitumen path site, a process that required meticulous planning, including marking burrows, digging carefully around them, and ensuring each spider was safely transported to the relocation site. We also detached and relocated the turret entrances from the spiders’ previous burrows in the hope of providing a sense of familiarity to their new homes. Our initial successes in this set the stage for a more extensive rescue effort as construction deadlines approached.

A summer rescue

We’d been monitoring the Tree-in-a-rock colony for about six months and had successfully moved five spiders. By January 2024, the weather had become too warm to do spider research, as many trapdoor spiders aestivate – go into summer hibernation – to wait out the worst of the heat. The start of construction had been pushed back a few times and we were hoping it wouldn’t commence until at least May 2024, so we could resume monitoring and moving spiders in April, when the weather cooled down again.

But we wouldn’t be that lucky and were notified on 18 January that construction was commencing on 29 January. We felt very far away, being in Perth, but sprang into action. Assisted by the incredible coordination efforts of local legend Loxley, a week later on 25 January, we arrived at Tree-in-a-rock picnic area and were met by 22 volunteers from various conservation groups around the Great Southern region.

A summer rescue presented us with multiple challenges. In January, the earth is hard, even in a wet karri forest, and a spider that takes only 30 minutes to dig up in the cool seasons can take more than two hours to safely excavate in the heat. This meant we would likely rescue fewer spiders in summer than in winter. The extra effort required to dig them up also increased the risk of harming them during removal. What concerned us most was that the firmer ground meant the spiders had to work harder to dig new burrows once they were relocated.

It’s a big risk for a trapdoor spider to be outside of its burrow, because trapdoor spiders evolved during the time of Gondwana, when the humidity was much higher than it is today. The inside of a burrow retains high humidity and stable temperatures much like a cave does, and living in burrows means these spiders have prevailed even though the climate has largely dried out. However, if they leave their burrow they are vulnerable to desiccation, where they dry out through their lungs and perish. We needed to dig the spiders up and get them back underground as quickly as possible to keep them from losing too much water.

Rescue assembly line

We had four days – Thursday, Friday, Saturday and Sunday – to carefully dig up as many trapdoor spiders as we could. The first step in bringing up a spider is the most time-consuming one. It involves digging an access trench straight down alongside the burrow so you can approach the spider from the side and gently pry it out. They can retreat quite deep when they sense you digging so that access trench may need to be 60cm deep and 30cm wide. Only Leanda had the expertise to complete the second step, which was to extract each spider from its opened burrow. The third step was transporting the spiders 100m away to the relocation zone.

Between us all we made a plan and devised a rescue assembly line. During the four days, the volunteers dug 40 trenches alongside the bigger burrows, a huge effort involving breaking up the hard dirt with pickaxes and navigating around buried rocks. Once a trench was dug, Leanda stretched out on the ground, long forceps and feather forceps in hand, and gently and painstakingly removed each spider. We were very careful when we came across gravid (pregnant) spiders and spiderlings, which are particularly vulnerable when disturbed in any way.

Each spider was then transferred in a container to the relocation zone, where Cass was set up with trowels and flags. A suitable patch was allocated, and a shallow burrow was dug with a narrow trowel. The spider was gently decanted inside, then covered with soil, leaves and a plastic dome cover. Both species are likely nocturnal and this protected them until they could start building themselves a new burrow at nightfall. The spiders were recorded in a grid book and identified with a flag.

The field work became a fast-paced, high-stakes effort to save as many spiders as possible before the construction crews arrived. The few times we managed to stop for breath and look around we saw the incredible volunteers hard at work digging trenches, handing out water, and crouching over burrows with umbrellas to make shade for the spiders coming out. The continuous stream of trapdoors being brought to the relocation site was very rewarding. After being trained and supervised by Leanda, a few volunteers had even brought up spiders themselves, increasing the number saved.

By Sunday 28 January 2024, we’d moved 40 spiders out of the path of construction and into the relocation zone. This was only possible with the help of Loxley and the volunteers, as we might have only rescued about 10 spiders in the same amount of time by ourselves. We’d done all we could, construction was due to begin the next day on Monday 29 January. We had to thank our volunteers and head back to Perth.

Important totems

Construction took about six months and the spiders were on our minds the whole time. The rescue was more than just about saving spiders – it was a test for our capacity to fulfill our responsibility to care for Country. We both consider the trapdoor spider to be our borangka, or totem, a Noongar concept where you’re expected to be an expert on a particular plant, animal or element, and you’re responsible for directing the rest of the community on how to treat your totem to ensure its ongoing survival.

The place-name ‘Porongurup’ translates as Borangk-up, meaning ‘place of totems’, as well as Boorong-up, ‘place of rain’. It is a place for honouring totems, so when the sign went up announcing the planned construction, it felt like a challenge being placed before us: will you act? We had answered the call and done what we could, and now all we could do was wait.

Successful new colony

In July 2024, we finally found ourselves once again driving the long, beautiful road up the mountainside, beneath the towering karri trees to see the results.

The picnic area was transformed: new paths, new gazebos, new seating and new toilets. We walked along the new bitumen path, noticing that the meandering lines of spider burrows along its edge had been replaced with mulch. We walked into the forest to the relocation zone and saw our colourful flags rising from the leaf litter. As we looked down into the relocation zone we saw burrows everywhere. We spent a few hours surveying, checking each flag, and marvelled. Early signs point to every single spider having survived the move. We gave the relocated colony its own name, the Kara Koorl Colony, which is Noongar for ‘spiders that have moved’.

Walking out, we checked along the mulched edges of the new bitumen path again, looking for any signs of life. And there it was: a Cataxia burrow poking up among the wood chips. It was a large burrow, 2cm in diameter and 2cm tall. Instead of the turret being made of karri leaves, sticks, and flower petals, it was a little fortress made of spiky wood chips.

Our only guess is that a large female we missed during the rescue had dug deep enough so that she’d managed to escape the shovels, diggers and compactors. When all the noise and vibrations stopped she must have popped up and built herself a turret from what was around her.

We’ll keep an eye on her to see if a woodchip burrow can serve its purpose, but her survival offers a lot of hope for the resilience of these tenacious, deep-time matriarchs that live in the undergrowth.

The power of collaboration

Seeing the community come together to save spiders was not only incredibly touching, it was crucial to the success we had. Early on in the project we chose collaboration over protest, largely because there were no specific laws to protect the spiders, and the bitumen path would be laid long before we got anywhere with changing that. It was a bitter pill to swallow, as we felt a strong sense of injustice that so many spiders were going to perish for the convenience of humans.

During the course of the project, however, we found that with collaboration came an infectious, positive energy that ultimately attracted the people who showed up in droves to help. That positive energy also sustained us through the nearly year-long survey and research effort.

We couldn’t have known it at the time, but having 22 other people to share in our sadness and happiness helped us carry the grief for the spiders that perished in the construction process. In the course of being tested in our dedication to our totem, it seems that Country was also teaching us the lesson that it’s not individuals who successfully protect Country, it’s communities.