The article is sponsored by Heritage Expeditions.

There’s a softness in the ocean this morning as we step from our mothership, the Heritage Adventurer, onto Zodiacs, the rugged inflatable craft used for explorations here along the remote Kimberley coastal region of Western Australia. Encircled by craggy, rust-coloured cliffs, this vast ancient land holds many secrets of the world’s creation story, while presenting an impressive canvas of rugged ranges, mighty rivers, phenomenal reefs, giant whirlpools and remarkable wildlife. It can also pack an adventurous punch. We had no inkling that things were about to get a bit more lively on our peaceful morning outing along the broad Hunter River.

Dusky pink dappled light creates faultless reflections of the riverbank as we seek to spot crocodiles, dolphins, mudskippers and myriad other species that call this juxtaposition of environments their home. So many organisms live together here – mangroves, seagrass and other marine plants, animals, algae, and corals and crocodiles – and are recorded in the region’s greatest numbers.

It doesn’t take long for us to find our first adolescent crocodile, roughly 1.5m in length, with only the interconnected dorsal plates of his back and the vertical, sail-like scutes of his tail visible. But as quickly as we see him, he’s gone with nary a ripple.

Surrounded by mangroves, Steve Bradley, our Zodiac pilot, turns off the engine to savour the stillness of the river and listen for the calls of kingfishers flitting through nearby low-hanging branches. Unbeknown to us, beneath the surface a well-planned ambush is about to be executed.

Without warning, a flying, would-be ‘assassin’ mars the peace. Steve is struck in the chest by an unknown critter, causing a minor commotion. Amid amused passengers, a bit of banging and a yell or two, he pats himself down, obviously unhurt but possibly thinking he’s been hit by a flying croc.

“Can you imagine?” says Steve, recalling the encounter later over a well-earned beer. “We had just observed this young crocodile disappear, and then out of nowhere I’m blindsided by a flying missile. What would you have thought?”

As the calm reappears on the Zodiac, we realise a panic-stricken barramundi is flapping at our feet. The huge fish has successfully launched itself into the craft, away from the jaws of a hungry crocodile.

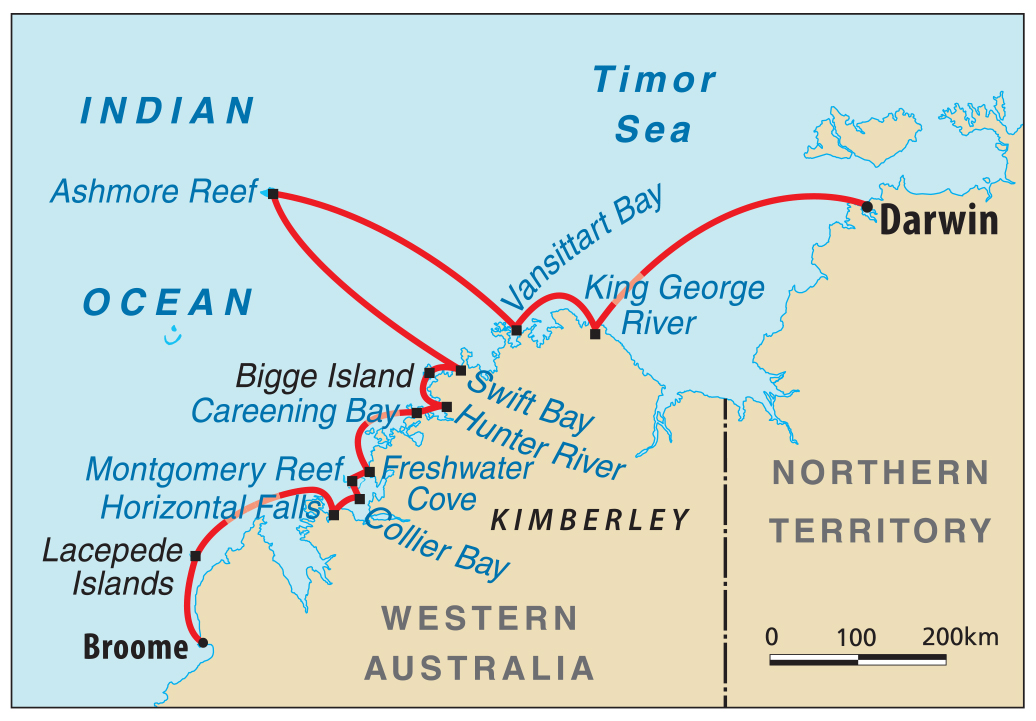

My 10-day voyage from Broome to Darwin with Heritage Expeditions, a New Zealand family-owned company, is packed with unpredictable stories, just as we learn each wall rock, cliff, cave, and river has its own unique tale to share. Heritage Adventurer carries just 140 passengers and sails around this timeless land, an area of 423,517km2, taking passengers to places that are largely unreachable via terra firma and are recognised as some of the world’s last undamaged coastal habitat.

Our itinerary provides a daily assault on the senses that begin the moment we pull away from Broome dock, heading towards a blood-red horizon. We are accompanied by humpback whales diving and splashing beside us, silhouetted by the sunset. A direct route across the top of the Kimberley is approximately 800km by sea, but there’s actually 12,800km of detailed coastline to explore if you follow the nooks, crannies, bays and inlets.

Life here is dictated by the tides. A giant tidal range of up to 12m means that if you get your calculations wrong, even by half an hour, you can find yourself high and dry on a mud bank, or marooned on a reef with a six-hour wait to be refloated. We witness the power and might of this on our first day in Talbot Bay, where a natural phenomenon of tidal water rushes through two narrow rock gaps in the McLarty Range, forming a horizontal waterfall (known as Garaangaddim to the Dambimangari people), within the Lalang-garram/Horizontal Falls Marine Park. Huge whirlpools, up-currents and rapids power through the gaps at a rate of 10–15 knots, reversing as the tide changes, and providing an exhilarating look into the turbulent flows that are most evident during the two spring – or king-tide periods of each lunar month.

In the past, this was marketed as a thrilling boat adventure, but due to a series of accidents and the Dambimangari Traditional Owners’ request to not negotiate the falls by boat when the tide is rushing (they believe the tide rushing is the Woongudd – the creator snake), visitors are now encouraged to witness this event without the rush of the ride.

Our Zodiac continues up nearby Cyclone Creek for a deeper look at the astounding rock wall formations of the area, displaying a history of the earth’s movements, hundreds of millions of years ago, when the main horizontal formation of the Kimberley Basin folded into mountains and valleys.

Day after day there are new things to see and experience. At Widgingarra Butt Butt (Freshwater Cove), the local Arraluli people perform a welcome ceremony and walk us upwards through the spinifex to an overhanging cave filled with rock art – stories left by their ancestors.

“This is like a library,” says Leon, a local Worrorra youth, with a huge gleaming white smile. “These caves are like your computer. This is a learning site, that’s why we’re allowed here. Each painting has a deep story connected to it. Like these two nightjars painted here. This is the story of our skin groups, our blood groups, this is how we know who to marry. It’s a story of our kinship.

“Later on, when we finish here, we will walk you through a smoking ceremony. This ensures you leave any bad spirits here and keeps you safe as you travel. We use this for all kinds of stuff,” he adds.

There is much to learn about this, the oldest continuing culture in the world. There is no written history. This living culture has been passed down with song-line, dance, stories and art. We visit several other rock-art sites as we journey through the Kimberley, witnessing different styles of art, including Wandjina paintings and remarkable walls of Gwion Gwion rock art, said to date back anywhere from 5000 to 60,000 years.

From the art, we move to reef. There’s an air of excitement around Montgomery Reef, as our arrival is timed to a dropping tide. Over the next couple of hours, before our eyes, we watch as the world’s largest inshore reef system emerges from the ocean.

The scene begins mildly, with water draining from the top of the reef. Birds fly in, alerted and sensing it’s tucker time. As the tide continues to drop and this ancient terrestrial tableland becomes more exposed, water gushes and cascades off the reef edge, forming a line of waterfalls off the sides. The high-velocity tidal flow forms a rich bowl of nutrients at the base of the reef, attracting all sorts of feeding wildlife. Below our Zodiac, huge, plump, batfish hang in the current, a shark feeds in the shallows, and turtles’ heads pop up all around. Landing in front of me, a stark-white eastern reef egret plucks a tiny fish from the rapids, the afternoon backlight accentuating every detail of its feathers.

One of our guides makes a radio call. “Guys, I have a sea snake here. Actually, he’s following us. Staring at us. Should I be worried? Joking!”

It’s a reef system like no other, described by Sir David Attenborough as “one of the greatest natural wonders of the world”, formed some 1.8 billion years ago, and recognised as one of the most significant geological marine environments in the Kimberley.

Then there are the birds. Our itinerary takes us 630km north of Broome to the rarely visited Ashmore Reef Marine Park, in the Australian External Territory of Ashmore and Cartier Islands. The park has the largest emergent oceanic reef in the north-eastern Indian Ocean, surrounded by vegetated islands. Long before we arrive at our mooring, the skies begin to fill with passing terns, boobies and frigates. These islands teem with 100,000 breeding birds each year and provide a stop-off point for many migratory species.

Most of this area is a sanctuary zone, so we have strict guidance laws for access. Our Zodiacs aren’t permitted to land, but at high tide we can cruise relatively close to the islands. Flocks of noddy terns, sooty crested terns, brown boobies and frigatebirds rest on the vegetation and shoreline. There have been 179 bird species recorded here; above us, the sky is thick with wings. Hovering over my head, a brown booby just an arm’s length away eyeballs me. With no fear of humans, another lands on a guide’s head and proceeds to sit there for 10 minutes, just taking a rest.

Deemed far enough away from the mainland not to encounter a crocodile, we also get to snorkel here. In the past, Ashmore Reef sustained a period of heavy illegal fishing activities, but with Australian Border Force now near-permanently stationed here, it’s heartening to see a huge diversity of colourful corals showcased through the window of my mask. Fish life is returning, and it’s an absolute privilege to visit such a pristine and abundant outpost – one of the many benefits of travelling by boat.

Returning to the Kimberley coastline, we rise before the sun to catch the tides, venturing into crystal-clear bays and bathing beneath waterfalls. I learn about mangroves (and they grow on me) – these intricately interesting and hugely important little forests where mudskippers and fiddler crabs hang out are not muddy, smelly, mosquito-infested swamps. Mudskippers are my new favourite thing; I make our Zodiac pause for longer than I should while we watch fights over territory and potential mates, the males intermittently sucking their huge, bulbous eyes right back into their heads and rolling over in puddles to keep themselves moist.

If you are a history buff, it’s here in buckets. At Vansittart Bay on the Anjo Peninsula, we walk across a mudflat to a World War II C-53 aircraft crash site, and at Careening Bay we learn about Lieutenant Phillip Parker King, the first man to accurately chart the Kimberley coast. We wander through aged cabbage-tree palms and admire ancient, fecund-looking boab trees, caressed by the soft sea breezes.

We are escorted up the King George River by 80m-high sandstone cliffs, to be met by twin waterfalls, tumbling from the plateau above. In the estuaries, we spot snubfin and humpback dolphins, even a manta ray. And, of course, we are always on the lookout for a flying croc.

In fact, at Jar Island we rounded a mangrove-clad corner, towards the jaws of the biggest crocodile I have ever seen. It was sunning itself on the bank, mouth open and pointed teeth twinkling like a Colgate commercial on steroids. By popular poll, we decide there is no way that crocodile will ever fit in our boat, so we politely turn and leave. We didn’t ask if he was fishing.

Cruising onboard Heritage Adventurer is akin to a mythical quest, and the Kimberley region is a dreamy insight into what feels like the pulsing heart of the beginning of time. I feel small, but intrinsically connected to this big, bold, beautiful land. At the end of my journey, it is fitting to listen to a video where a local extends an invitation, “We all have the ability to connect with Country. It’s whether we allow ourselves to do this.

“I offer you to sit on Country and share your story.”

The article is sponsored by Heritage Expeditions.