Escape to an island where it’s always Christmas

This article is brought to you by Australian Wildlife Journeys.

When Sir David Attenborough describes an experience as “one of his greatest TV moments,” you know it’s next-level incredible.

The world-renowned naturalist is referring to Christmas Island’s annual mass red crab migration, where millions of these crustaceans emerge from the forest and move en masse to the ocean to breed. Swarming across roads, streams, rocks and beaches (and David during his visit), it’s one of the most incredible natural processes on Earth.

Image credits: Christmas Island Tourism Association; Justin Gilligan.

Lisa Preston, owner and founder of Indian Ocean Experiences, knows the island better than most. “I proudly call myself a local,” she says. “I’ve been based on the island for more than 26 years and have been operating tours for 17 of those.”

The rocky outpost is located 2600km north-west of Perth and 450km South of Jakarta. It rests on the precipice of the Java Trench, and is surrounded by rugged cliffs, coral beaches and tropical reefs that teem with life.

“Christmas Island has more than 90 different species of crab,” says Lisa. “And 28 of those are land based. The most abundant are the red crabs, of course, and the three most visible are the red, blue and robbers.

“Red crabs can generally be seen year-round and blue crabs congregate at the natural spring areas on the island. They prefer a muddy burrow. All 28 species use the ocean as part of their breeding cycle – they’ve all evolved to live on land, but for spawning they launch their eggs into the ocean. They use different moon cycles to do this so they are spread out across the month – usually during the wet season [November–February].”

While famous for its 10-legged reds, the island’s robber crab (Birgus latro) shouldn’t, or more fittingly, can’t be missed. The largest-known terrestrial arthropod, it weighs in at a hefty 4.1kg and has a distance of 1m from the tip of one leg to the tip of another.

“Most other places call them coconut crabs due to their penchant for and ability to break into coconuts,” Lisa says. “On Christmas Island we call them robber crabs – latro in Latin means ‘‘highwayman’‘ or ‘‘brigand’‘ – so robber is actually a closer nickname to their species name. We have one of the largest populations on Christmas Island – they’re protected here.

Image credit: Australian Wildlife Journeys

Christmas all year round

According to Lisa, if you want to see the proliferation of crustaceans, wet season is the time to visit, but be warned – it’s hot and humid. “Many of the island’s tracks get closed off to vehicles to conserve and protect the migrating crabs. People are welcome to still enjoy the locations on foot, but several extra kilometres can be added to your walk to get to the location, which can be arduous for those not acclimatised or used to walking reasonable distances, sometimes up and down hills.

“Everyone wants to be here during the migration, but actually, it’s almost like you need two visits – one during the dry season to visit all the locations, and then again in the wet to focus on the abundance of crabs.”

Of course, there’s an array of other animals to delight on the island, and birdwatchers in particular will delight in the feathered varieties.

Exotic gifts

“Birds are everywhere – all the time!” Lisa says. “Christmas Island boasts one of the most beautiful birds on the planet – the golden morph of the white-tailed tropicbird, or golden bosun. Its mesmerising aerial acrobatics and distinctive call can be heard all around the island.”

Image credits: Inger Vandyke; Chris Bray.

Other unique species that call the island home include the critically endangered Christmas Island frigatebird and the endangered Abbott’s booby. “We are its last stronghold,” Lisa says. “Many folks are under the impression that it’s the red crab conservation that stops new mining activity on the island, but it’s actually the booby. It needs tall, old-growth forest trees on the top plateau for nesting and breeding, which means the trees cannot be cleared.”

Image credit: Australian Wildlife Journeys

For a relatively small land mass (just 135sq.km), the island boasts a high level of endemism, supporting five endemic species and five subspecies, including the Christmas Island imperial-pigeon, hawk-owl and white-eye.

“In total, the island has 23 breeding or resident species – nine sea and 14 land – and they’re extremely important to the ecology on the island and need protecting,” Lisa says. “The phosphate mining has contributed to significant habitat loss in some locations, any further habitat loss will result in pressure on the populations of birds. We only have about 250 different plant and tree species, which is quite limited, and therefore limits the bird and insect life that we can support. This is why conserving our remaining rainforest areas is of key importance.”

Unwrapping history

The geological history of the island – jagged inland terraces and ocean cliffs, covered in Jurassic-style rainforest – remains a bit of a mystery, Lisa says. “Nobody is really able to provide definitive answers on this. What I have been able to piece together is that we are an oceanic island (never before linked to a land mass), a volcano formed from the ocean floor and boosting the island out of the water.

Image credits: Chris Bray; Garry Bell

“There may have been multiple re-submersions to allow a coral cap to grow over the top of the island, which then has been once again boosted out of the ocean. There are fissures of volcanic activity during that period, as we have spring areas on the island where basalt is present on the top and just below, preventing the water from percolating through the limestone coral reef.

“Between the coral and sea life, and the possibility that the island may have provided a protected rookery for a long-extinct seabird, large and rich deposits of phosphate became compacted around the old reef, providing an exportable resource – rock phosphate. This is used as quite a raw product – not much processing. It is a slow-release fertiliser, namely used on palm oil plantations in Southeast Asia.”

Dive on in

What is a certainty, as a result of the island’s formation, is it’s skirting coral reef – and the aquatic life here is second to none.

“Flying Fish Cove is one of the protected ocean areas on the island,” Lisa says. “The hard coral is healthy, there are plenty of ‘‘gardens’‘ to explore, and in a 30-minute snorkel, you can see up to 40 different fish species, all within just a few metres of the shore.

“A swim around the jetty of an afternoon can provide extraordinary views of schooling fish, octopus, rays and lion fish.

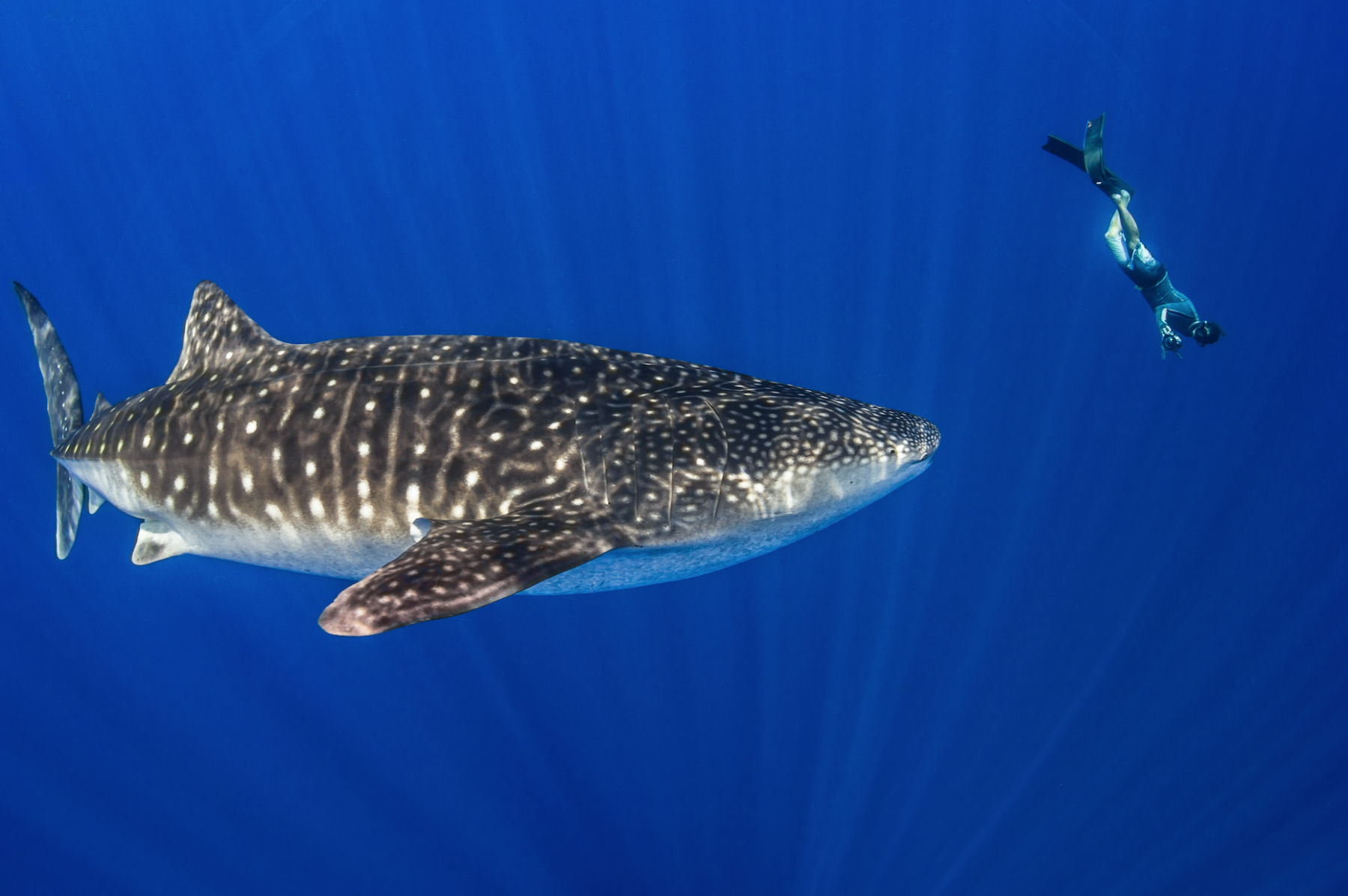

“The diving is amazing. We have some great wall diving, which includes intact fan corals, batfish, several different shark species, nudibranchs, shrimps, eels, and during our wet season, whale sharks.”

And if you’re an open-water diver, you’ll froth at the slow current immersions with 30m+ visibility. For the more adventurous, wall diving, cave diving, deep-blue diving and nitrox diving are all on offer.

Image credit: Kirsty Faulkner

Indian Ocean Experiences is part of the Australian Wildlife Journeys collective. Find out more here.

This article is brought to you by Australian Wildlife Journeys.