Try saying this slowly: garnamarr (pronounced ‘gunna-marr’, but roll the last part by vibrating your tongue against the roof of your mouth). You’ve just learnt a new Indigenous word from the Top End of Australia and mimicked the voice of one of the world’s most magnificent birds, the red-tailed black cockatoo (Calyptorhynchus banksii).

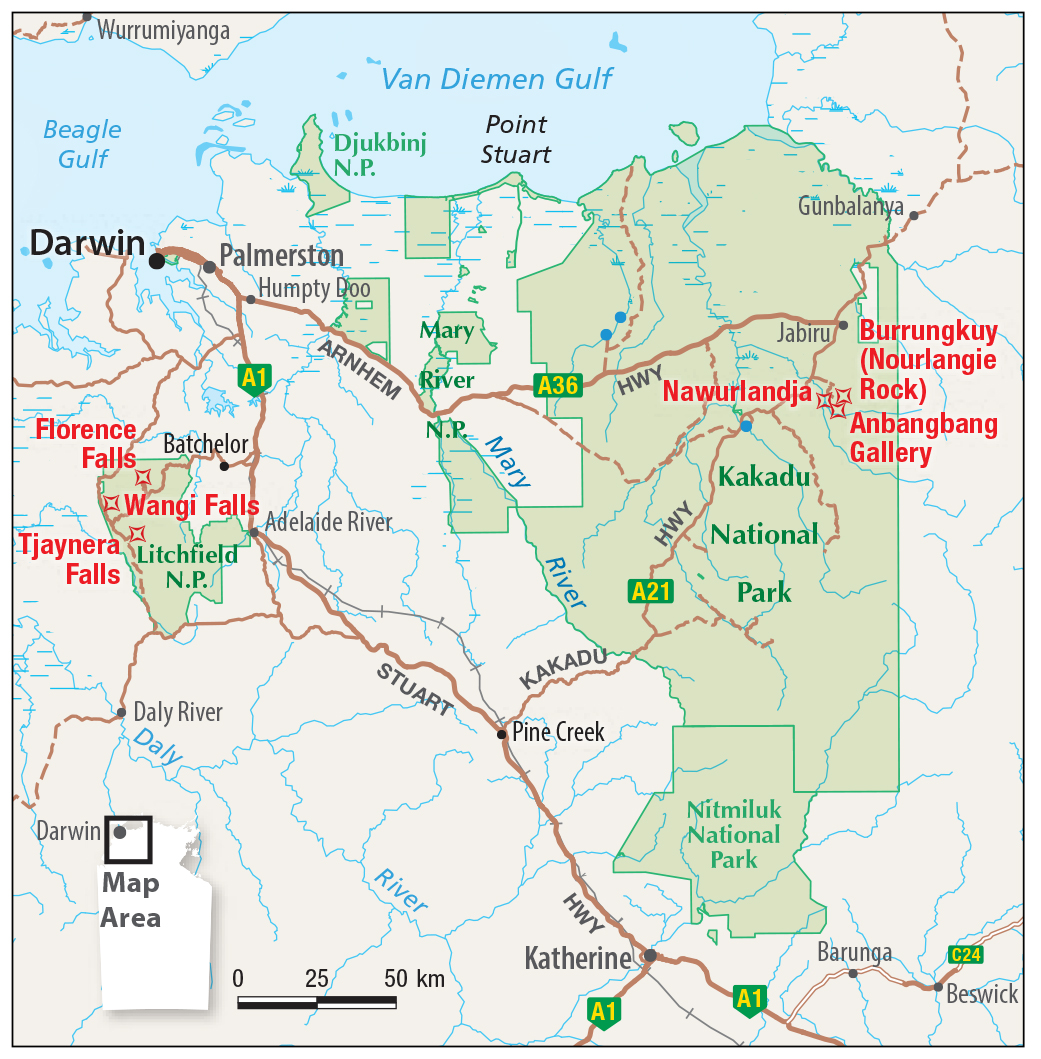

To me, these birds epitomise the wildness and freedom of the Top End. My partner Janine Duffy and I experienced this on our first visit to the region as we returned to the town of Batchelor from a day out in Litchfield National Park, just an hour’s drive south of Darwin in the Northern Territory. We had seen one or two garnamarr earlier in the day, but nothing like what we were about to witness.

As the tropical sun began its rapid descent, we drove east through the savanna woodlands. Suddenly, a large flock of garnamarr appeared above the treetops, their red-and-black plumage flashing in the fading light. More than 100 birds flew overhead, their beating wings and far-carrying calls creating a mesmerising scene – garnamarr, garnamarr, garnamarrrrr – until they disappeared into the night. It was the kind of moment that makes you realise how inconsequential you are, and how lucky you are to be alive.

This all happened at the end of Territory Day, which commemorates when the NT achieved self-governance on 1 July 1978. You must experience Territory Day at least once in your lifetime. It’s absolute bedlam, celebrated by a seismic blasting of fireworks across every town and settlement in the NT.

We arrived back at our B&B in Batchelor, just across from the football ground typical of many country towns – a grass oval surrounded by a water-pipe handrail and trees. The only light was a dull torch flashing around the centre of the oval where two men were setting up the show.

I walked over, curious, when suddenly there was a huge whoosh followed by a loud bang as the first of many pyrotechnics erupted into the night sky. I looked around to see dozens of First Nations people watching from behind the safety of the handrail – a uniquely NT event unfolding in this small, remote town.

“Not bad this year, eh?” said a soft voice nearby. It was a local Aboriginal woman. I admitted I hadn’t seen this before. She asked, “You from down south?” Surprised, I replied, “Yes. But how could you possibly know that?” “I can tell you’s not from ’ere,” she said. Even in the dark, during a fireworks display, this woman was telling me that this is her place – where she comes from, her Country, and that she knows what’s going on and who’s who.

We chatted briefly. When I mentioned the black cockatoos, she smiled. “You okay for a bloke from the south. You got the bush in you. In my language them birds are called…” A deafening bang cut her off. “That’s all folks!” yelled one of the men in the oval. He shot one last flare skyward and then took off towards the pub.

I turned back to ask my new friend what “them birds” were called, but she’d vanished into the night along with most of the crowd. It wasn’t until years later that Janine, while researching our tours, discovered the word garnamarr. Since then, we’ve always used that name for the cockatoos.

Litchfield National Park’s unique charm lies not only in its natural beauty but also in its accessibility and year-round appeal. Unlike other Top End parks, Litchfield NP’s streams flow even during the Dry (May through October), making it a haven for wildlife. It has sandstone plateaus, monsoon forests and bushland, all of which most visitors allocate only one day to enjoy. In my opinion, that’s crazy, as you’ll hardly scratch the surface of this wondrous park.

During our two-week stay, we explored Litchfield’s diverse landscapes – its plateaus, waterfalls, billabongs and crystal-clear creeks. One particularly memorable hike led us through dense monsoon forest and then up a dry, rocky slope. There we found a natural infinity pool with breathtaking views over the escarpment to an untouched, forest-covered plain. It gets hot in the tropics, so we stripped off and stepped into the cool water. It was one of the most magical and romantic moments of my life. No other infinity pool will match it.

If you go there, be gentle: treat it with respect and you’ll hear the Old People (Aboriginal ancestors) murmuring in the water. They may even let you see the brightly coloured rose-crowned fruit-dove (Ptilinopus regina).

To understand the Top End, you must recognise that the Old People are close by wherever you go, watching and listening. I like to think garnamarr is their envoy, because sooner or later she will show up and lead you to a new place – and it will usually be around sunset (maybe because she likes the way her partner’s tail lights up red at that time).

We saw her and her mob drifting over Nawurlandja in Kakadu NP, a two-hour drive east of Litchfield, as we watched nearby Burrungkuy (Nourlangie Rock) burn bright red like garnamarr’s tail in the setting sun. Eastward, in the distance, one of Namarrkon’s djang (the Lightning Man’s sacred place) towered gold and red on the walls of the Arnhem Land escarpment. You can find a depiction of omnipotent Namarrkon in the Anbangbang gallery at the base of Burrungkuy. If you’re lucky, you may even see one of our rarest kangaroos, barrk (the black wallaroo / Osphranter bernardus), hopping down for a drink at one of the nearby billabongs where he might meet djakarna – the black-necked stork, or jabiru (Ephippiorhynchus asiaticus).

Garnamarr might even lead you to one of her (and my) favourite places: the Mary River, an immense 250km-long watercourse with a catchment of 8000sq.km. I’ve never really understood why this river is so little-known, because it’s one of Australia’s most remarkable waterways. It originates about 50km east of Pine Creek and flows northward, skirting Kakadu NP. It then meanders through the Mary River NP, a mosaic of pastoral land and protected areas, before ultimately emptying into the Arafura Sea near Point Stuart. The catchment crosses every major highway to the east and south of Darwin. And yet, remarkably, most travellers don’t know of its existence.

Garnamarr loves the Mary River too. She inhabits its source in the south all the way to its horizon-to-horizon floodplain in the north. In summer, the Mary pours 2400 gigalitres of monsoon rain into the Arafura Sea. In fact, over the years it has brought down so much silt that in the Dry it dams itself 25km from the sea at what is known locally as the Shady Camp barrage.

You can visit Shady Camp in the Dry. On the upstream side you’ll see kinga (saltwater crocodiles / Crocodylus porosus), while below the barrage the river turns to grey sludge for part of the day until the incoming tide comes up almost level. One side is freshwater, the other is salt. Kinga of immense proportions slither backwards and forwards across the barrage. Hundreds of agile wallabies (Macropus agilis) dart among the trees. Dingoes sometimes come in for a drink. Huge channel-billed cuckoos (Scythrops novaehollandiae) – the world’s largest cuckoo – fly in from Papua New Guinea and hurtle around the place like jet fighters, screaming maniacally.

There’s birdlife everywhere you look, from manimunak (magpie geese / Anseranas semipalmata) and Australian bustards (Ardeotis australis) all the way down to tiny crimson finches (Neochmia phaeton). I’ve never seen more species of raptors than I have at Shady Camp. At sunset, chains of ngalkordow (brolgas / Antigone rubicunda) and glossy ibises (Plegadis falcinellus) grace the reddening sky with their slender silhouettes.

There are so many more places garnamarr can take you in the Top End, but the only way to find out is to go there and listen for her cries: garnamarr, garnamarr, garnamarrrrr. Then let her teach you her kunmayali (wisdom). You’ll return home a different person.