Mighty Morton

GEOLOGIST PHIL SMART leads us down an trail through filtered light in dense eucalypt forest on the eastern edge of Morton National Park. On each side, the wide trunks of turpentine trees rise 50m or more above us – the fallen leaves underneath smelling faintly of acidic resin. We are clambering across the rocks of the Sydney Basin, once the bed of a long-gone sea.

Bending down, Phil picks up a fossilised piece of echinoderm, a prehistoric relative of today’s starfish and sea urchins. Fossils are everywhere, this is one of several he’s pointed out in the last 10 minutes. “That’s the fauna that was living on the seafloor here 270 million years ago. By 200 million… this was no longer the coast,” he says. “The Tasman Sea opened up from about 84 million years ago. By 60, it was completely opened up, and the rebound lifted these rocks up hundreds of metres all the way from Mt Bartle Frere in Queensland right down through Tasmania – that’s the eastern highlands of Australia.”

Morton NP’s entire length runs along these highlands, starting roughly 100km south-west of Sydney to its spectacular steep southern extremity, about 80km east of Canberra. It’s the fifth-largest national park in New South Wales. Like many others in this part of the state, it is defined by a sandstone-derived landscape of steep outcrops and nutrient-poor soil, which supports hardy eucalypt forest and shrubby, biodiverse vegetation on its plateau tops.

Stretching across the winding waterways and rapid runs of the Shoalhaven River, Morton includes spectacular waterfalls, glow-worm caves at Bundanoon and orchid-laced gorges in the Ettrema Wilderness. A bushwalker’s favorite also hides in Morton’s south – the jigsaw of jagged pagodas, mountains and mesas of the Monolith Valley in the northern Budawang Range.

At 1997sq.km, the park is almost the size of the Australian Capital Territory, and an incredible three-quarters of this is inaccessible by public road. This area is protected by a wilderness designation – an attempt by conservationists to keep a large portion of land untrammelled and unaltered by development.

Geologist Phil Smart explains how ancient seas created the beautifully layered sandstones and also left scatterings of marine fossils in the area. (Image: Jake Anderson)

MORTON’S WILD INTERIOR is a sanctuary for wildlife, particularly large arboreal fauna, says David Duffy, who runs landscape tours with Phil for the NSW National Parks and Wildlife Service (NPWS). The powerful owl, Australia’s largest owl, roosts in the big trees around us. “Being a night creature, you mostly hear them rather than see them,” David says. Occasionally, however, you’ll come across gruesome evidence in the form of fluffy glider tails underneath a tree.

“It’s the first thing they do, look at that bit of fluff and think, ‘I can’t eat that’ – and snip it off,” he says. These large predators need a range of 400–4000ha per breeding pair, and David says they only live in the hollows of trees more than 150 years old. “When you hear about animals like that, you realise how important it is to have such a large wilderness park,” he adds.

The owl’s main prey is another charismatic tree-dweller, with large, white furry ears and that long fluffy tail. At up to 1m (nose-to-tail), the greater glider is Australia’s biggest, and it uses the flaps of skin stretched between its wrists and ankles to swoop up to 100m between trees. Both species are considered vulnerable, and are under pressure from the creep of agriculture to the west of the park. Alongside them are endangered brush-tailed rock-wallabies, critically endangered spiny crayfish, as well as threatened potoroos, koalas, tiger quolls and more. The park is home to least 31 native mammals, 176 species of bird, 19 frogs, 14 snakes and 24 species of lizard (a total of 41 of these animals are rare or threatened).

Phil, David and I turn up the Yalwal Ramp to the plateau that forms most of Morton and is cut through by some of the most pristine catchments between here and Queensland’s Cape York. Silvery flashes in the shallows reveal the presence of one of the nation’s most endangered freshwater fish, the Australian grayling. Some say they smell as fresh as the waters they require – giving off a distinct hint of cucumber.

Scrambling single-file up a stepped rocky path we emerge at the George Boyd Lookout. A sea of green spreads out below us to each horizon, layers of sediment and vegetation occasionally breaking out into golden sandstone escarpments.

The peak of 720m Pigeon House Mountain Didthul is the standout feature. Known as ‘Didthul’ to the local people of the Yuin Nation, it is said to be an eel’s head that was cut off and stuck on the mountain. Its lonely, sheer-sided nub of brittle Nowra sandstone is defying the elements, and is perched on a gently curved conical base surrounded by mesas. You’ll find prehistoric marine fossils on its summit too, says Phil.

Glimmering along the coastline, 16km away to the east, are bustling coastal towns like Nowra and Ulladulla, while mist rolls over the fertile hills of Kangaroo Valley in the north. The cacophony of Sydney city life is only about four hours away, and Canberra just three.

Looking east from The Castle Cooyoyo, an 847m mesa in Morton’s northern Budawang Range. Pigeon House Mountain Didthul’s distinct form is visible in the distance. Former NSW premier Bob Carr called this the best view in the NSW park system. (Image: Jake Anderson)

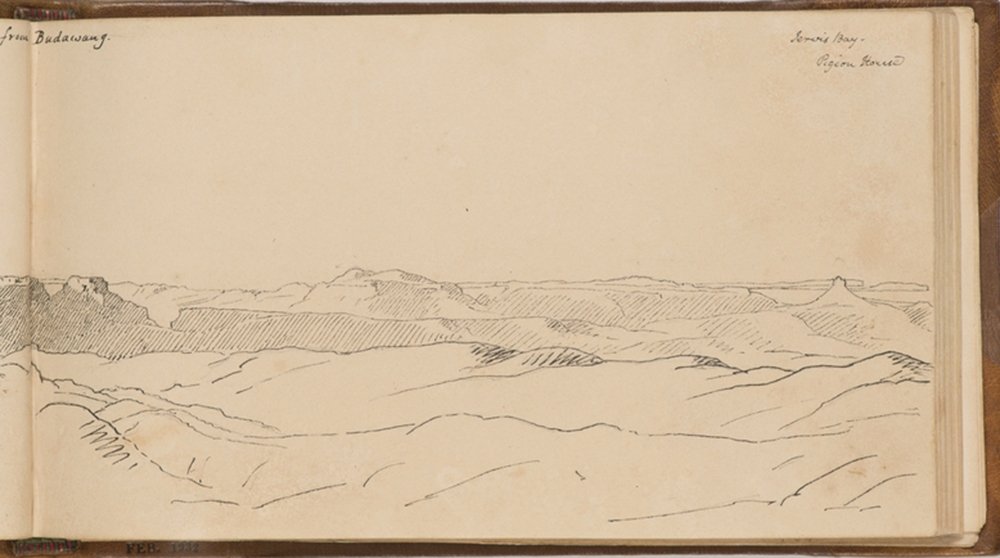

THE HISTORY OF NSW’s iconic bushwalking campaigners is interlaced with Morton’s. Not far from the George Boyd Lookout, legendary conservationist Myles Dunphy dumped his canvas pack in 1919 and sketched the Pigeon House Mountain Didthul and the northern Budawangs across the length of his diary, a notebook now in the archive of the State Library of NSW. It was, he noted, “the most perfect mess of mesas” he’d ever seen. By the early 1930s, Myles was agitating for the creation of Australia’s first ever wilderness area near Bundanoon, in Morton’s north (this is distinct from the first national park, Royal National Park – 80km to the north-east, that was gazetted for recreation rather than wilderness in 1879). The Bundanoon wilderness became Morton Primitive Reserve in 1938 – named after local conservationist and politician Mark Morton – and later in 1967, Morton National Park. As a result, Morton contains Australia’s oldest protected wilderness area.

The sandstone regions around Sydney were always a special place for Myles and his bushwalking brethren, the legendary figures responsible for campaigns that created the NSW national parks system, particularly Kosciuszko and the Blue Mountains. Perhaps their greatest vindication was international recognition of a number of these parks by UNESCO, when it listed the Greater Blue Mountains as a World Heritage Area in 2000.

Morton was part of the initial World Heritage proposal; the original area, however, was scaled back to meet a UNESCO deadline, and Morton was left out in the process.

The park gets about 453,000 visits annually, with about half going to the non-wilderness areas in the north, such as the Fitzroy and Belmore falls, which are beautiful sandstone drop falls easily enjoyed from viewing platforms and railed walks. Around Bundanoon too are glow-worm caves and many spectacular and accessible lookouts.

The Budawang Wilderness in the south, further from Sydney, but within striking distance of Canberra, sees just 20,000–30,000 people a year, with 60 per cent of these visitors going on the day walk up Pigeon House Mountain Didthul. But Monolith Valley is undoubtedly the most impressive landscape; a vast gauntlet of pagodas fractured into sharp relief by long-ago pressures. However, the valley gets far fewer visitors, requiring a challenging multi-day hike to reach it.

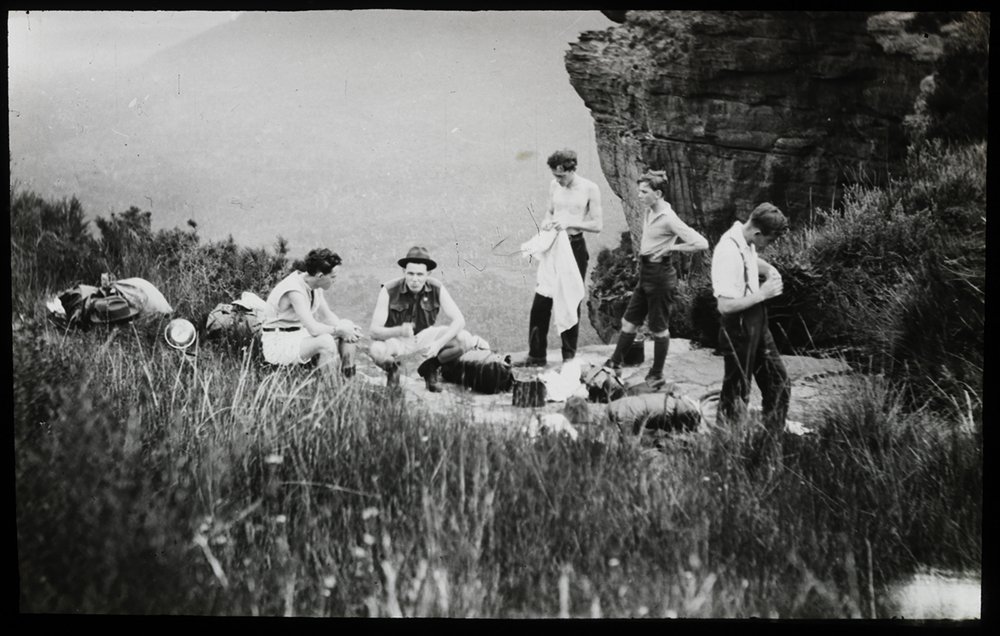

Top: An image from Myles Dunphy’s 1919 slide collection shows a group of bushwalkers taking a break on a sandstone escarpment. These expeditions led Myles’s cohort to campaign for the wilderness in NSW. Bottom: The Budawang Range, with Pigeon House Mountain Didthul on the right, is sketched across an explorer’s diary from the early 1800s (below). (Image credits: State Library of NSW)

This part of Morton has been one of the secret weapons of bushwalkers and their campaigns for more than 60 years, says 92-year-old Colin Watson OAM. We visit his home a few hours south of Morton in the coastal town of Moruya, and find Morton’s landscapes and characters covering his walls in black-and-white photographs.

As we settle in chairs in his small office, Colin tells us about the ‘Budawang Sketch Map’ tacked to the wall behind my head, which was drawn free-hand by his old friend and cartographer, George Elliott, during hikes they did together in the 1950s and ’60s. It was published by the Budawang Committee, which Colin founded in 1967 to promote the area, and versions are used by hikers to this day. Before the sketch map, says Colin, all he had to hike with was a parish map, one of which he pulls out to show us its few vague topographic outlines and nothing more.

“After we formed the Committee one of the first things we did was to petition the Geographic Names Board to properly name all of its features,” Colin says. “Sturgiss Mountain after Major Jim Sturgiss, one of the icons of the area, who lived in a hut up there; the Shrouded Gods Mountain after a poem he wrote; and Mt Elliott for George. It helped give it an identity and makes maps easier to read.” (Later, as we strode out to the Monolith Valley, we spot Colin’s namesake, Watson Pass, which leads to his favourite lookout over the valley.)

Other names have been anointed by different bushwalking clubs hikers say. The Byangee Walls, a sheer, prehistoric-looking mesa, was named by the Sydney Bush Walkers club, a crude combination of the surnames of members June Bryan and Ken Angle, and Pallin Pass was the conquest of Paddy Pallin, founder of the outdoor gear empire.

Only dedicated hikers knew of the area before the map, Colin says. Once the routes were published, however, regular bushwalkers learnt how to access spectacular Monolith Valley and soon they were there in large numbers, along with many Scouts.

Colin admits it was a strategy straight from the tactic books of Myles Dunphy, who mapped what are now the Blue Mountains and Kanangra-Boyd national parks before World War II. For Myles, getting walkers to use these areas was an effective means at drumming up support for protection; penetration of these wild places by bushwalkers and photographers infected the public with an enthusiasm for them. Indeed, thanks to Colin and many others who sang the Monolith Valley’s praises, by the 1980s bushwalkers were pushing for protection of the Budawang Range.

Later, when I call former NSW premier Bob Carr, he tells me that on his desk sits a picture of the late Milo Kanangra Dunphy, son of Myles. In 1976 the Helman Report identified only 20 areas in NSW large enough and pristine enough to still be declared wilderness, given that researchers then supposed that the minimum area needed to maintain the largest local macropods, eastern grey kangaroos, was 50,000ha. The Budawangs and Ettrema were on this list.

While Myles had written eloquent letters, Milo’s strategy to have these areas protected was more hands on. He took politicians into the wild. “Milo was an incredible man, and incredibly capable, although he could be absolutely dogged in his agenda,” says Bob, who traded suits for polo shirts and floppy hats when he ventured into the northern Budawang Range and other iconic areas with Milo on numerous occasions in the 1980s and 1990s. The ’80s was when Australians began getting serious about wild places – campaigns had been launched to protect Tasmania’s Gordon River from damming and the Colong Caves in NSW from mining, and Aussies began to talk seriously about protecting pristine spots from development.

A group of Sydney Bush Walkers club friends make their way through Ettrema Gorge in the west of Morton National Park. (Image: Jake Anderson)

By the 1990s public support for wilderness had swelled. The Sydney Basin bioregion was the most populous part of the state and Bob argues that, given population pressure, it was then the “last opportunity to save these remnants [the Budawangs and Ettrema]. If we hadn’t moved, development would have devoured a great deal of that,” he says.

As the NSW opposition leader, Bob campaigned on a wilderness agenda and won. After he became premier in 1995 one of his first acts was to declare seven new wildernesses and nine additions to existing wildernesses. He gazetted 1200sq.km of wilderness and old-growth forest between 1995 and 2005. Over the years, between Milo and Bob, national parks expanded from 2 to 5 per cent of NSW. It is one of the politician’s enduring political legacies.

Bob says he vividly recalls wondering what he was doing as he walked, sodden, with Milo “as the bush clawed at us” through the northern Budawangs towards the Monolith Valley in 1989. But among his other memories is the perfect vista from the top of the The Castle Cooyoyo, an imposing 847m mesa along the route. Its views sweep across Pigeon House Mountain Didthul and the Byangee Walls. From this height, he once said, he had the best view in the NSW National Parks system.”It’s the perfect combination; it’s mountain, eucalypt forest and a sweeping view of the coastline of Australia,” he tells me.

We marvelled at the same vie across the sea of undulating hills, picked out with shadows and tinged with gold, after a pre-dawn scramble to The Castle Cooyoyo’s summit. It wasn’t a bad way to end a week of walking in the vast NSW wilderness.

When to go

Morton NP has activities for every season. Paddlers can canoe down the Shoalhaven or Kangaroo rivers – autumnal rains create ideal conditions. Take the Three Views or Granite Falls walking tracks in spring to see wildflowers in colourful bloom (for very experienced bushwalkers, Ettrema Gorge is fringed with spectacular orchids). A number of walks, particularly around Bundanoon, take you through the cool rainforests in Morton’s gullies and deeper sandstone clefts. Serious uphill hiking and clambering, such as the kind done in the northern Budawang Range, is best done in the cooler months.

Getting there

By car, Fitzroy Falls is only 140km from Sydney CBD, and Pigeon House Mountain Didthul in the south is only 100km from Canberra, some of this on unsealed roads, but passable via 2WD. Google maps won’t register many unsealed routes through the park, so purchase topographic maps from the NSW Department of Lands, direct or online from a map shop.

Where to stay

Camping sites are plentiful, but bear in mind that many areas around Morton NP are weekend destinations for Sydney and Canberra. Kiama, Jervis Bay, Ulladulla, Nowra, Kangaroo Valley and Braidwood boast numerous places to stay.

Walking and cycling

Glow Worm Glen Walk

1-hour return

This short track just outside the historic highlands town of Bundanoon features a platform walk around which many glow-worms wink. They are only visible after dark. Access: Bundanoon

Pigeon House Mountain Didthul walking track

5km return, 2.5–3.5 hours

The iconic Pigeon House Mountain Didthul track features amazing panoramic views of the Budawang Range from the mountain summit. A climb of 500m leads to steel ladders

that help you clamber up the last steep sandstone nub at the top. Access: from Ulladulla or Braidwood

Fitzroy Falls to Kangaroo Valley cycling route

30km one-way, 8 hours

Combining scenic riding past undulating escarpment country with some steep downhill runs, mountain bikers can pedal past the magnificent drop of Fitzroy Falls to the Kangaroo Valley cycling route. Access: Fitzroy Falls Visitor Centre and Jacks Corner Road, Kangaroo Valley

Griffins walking track

11km one-way, 8–10 hours

In the north of the park, Griffins walking track offers a hike through the Yarrunga Creek Valley and up Meryla Pass. The walk is undulating and has some long, steep sections. Camping is available. Access: Kangaroo Valley or Moss Vale

Points of interest

– Belmore Falls

– Fitzroy Falls

– Glow Worm Glen

– Bundanoon

– Ettrema Wilderness

– Granite Falls

– George Boyd Lookout

– Budawang Wilderness

– Monolith Valley

– The Castle

– Pigeon House Mountain Didthul

There are many self-reliant bushwalking experiences in Morton NP. For example, the Ettrema Wilderness offers gorge country to explore. This is best reached by joining a bushwalking club. Bushwalking Australia: www.bushwalkingaustralia.org