Ningaloo Reef: No longer a secret

Anyone who says megafauna are extinct has never donned goggles at Ningaloo Reef. I roll off the zodiac into the water and when I open my eyes see a 2m mammal heading straight towards me. I duck dive down to the seagrass on the sandy bottom and watch nervously as the creature comes within a body length of my goggles. Its whiskered face is so close I can see its round chocolate eyes looking curiously into mine. The encounter’s so unexpected I feel a flash of fear – I have no idea if dugongs are dangerous. After only a few days at Ningaloo, however, I’ve already learned the prerequisite for swimming here – put your worries aside. This is the playground of some of the world’s largest and most gentle animals.

With a flick of its mermaid tail, the dugong lifts its 400kg bulk to the surface and examines my companion, photographer Andrew Gregory, who’s manning the outboard.

After a few minutes, it’s seen enough.

Surprising me with its speed and grace, the dugong is, within seconds, a rapidly disappearing shadow.

Ningaloo, not the Great Barrier Reef

The word Ningaloo belongs to the Gnulli people, traditional owners of the coast surrounding the North West Cape of WA. Ningaloo means promontory, but like everything about the stretch of coast between Carnarvon and Exmouth, the name is so much more than it first seems. Just saying Ningaloo conjures images of whale sharks and coral, wilderness and adventure.

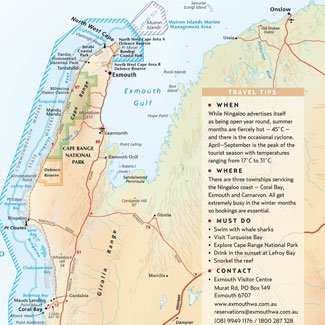

Ningaloo Reef map View Large Map

Imagine a promontory shaped like a beckoning finger, nearly 200 km long and jutting into the Indian Ocean. Try to comprehend a landscape that is one of the driest in Australia – with a mere 226mm of rain and an evaporation rate of more than 2.5m annually. Some years, if there isn’t a cyclone, it doesn’t rain at all. On average, the sun shines 320 days out of 365.

Ningaloo is famous not just for its reef, surf breaks and fishing but also its soul-destroying winds, white-hot 45°C temperatures and frontier-like feel. The harshness of the landscape, the swarms of native wasps and bush flies, the fine sand that blows into every nook and cranny, and the burning sun make its gentler moments seem like epiphanies.

Standing sentinel over the northern reef is the Cape Range, a rugged upward fold of limestone packed with fossilised prehistoric marine life including countless perfectly preserved shark teeth that are embedded in the rock and visible to the naked eye.

Inside the boundaries of the surrounding 47,655 ha Cape Range National Park is Mandu Mandu rock shelter, part of a massive system of sinkholes and caves that underpin the peninsula’s weathered spine. Here, archaeologists have confirmed the oldest evidence of the collection and use of fish, shellfish and crabs by indigenous Australians – an astonishing 32,000 years.

Ningaloo Reef itself stretches from the skyscraper-high military radio antennas, just outside Exmouth, southwards for almost 300km. It’s the nation’s longest fringing coral reef and the namesake of the 5218 sq.km Ningaloo Marine Park.

Anyone expecting to find a miniature Great Barrier Reef, however, has come to the wrong place. Instead of rainforest meeting the sea, it’s spinifex and sand dunes. Instead of big tourist cities like Cairns or Townsville, the Ningaloo coast has Exmouth with its population of just 2400. Visitors arriving at Learmonth Airport, 35km to the south of town, are as likely to meet a worker on their way to an oil rig or a defence official as a backpacker. In fact, upon landing, flight attendants request no one take any photographs for security reasons. Even so, the WA Department of Environment and Conservation (DEC) Ningaloo manager, Jennie Cary, says in terms of visitor numbers the region is growing fast. Annual visitation is around 300,000 she says, and increasing at 10 per cent a year.

Jennie has been coming to Ningaloo for more than 30 years. She first visited with her parents in the days when people came for one reason only – fishing for game such as sailfish and marlin and the prized reef species spangled emperor. She says back then no one swam because the popular belief was that Ningaloo’s waters were shark-infested. When swimming did take off in the late 1980s, it remained focused on the whale sharks. There’s no doubt they are still the biggest attraction for many visitors.

“In the 1970s, all people did all day every day at Ningaloo was fish,” Jennie says. However, that’s changing at a fast rate.

“Now we’re seeing a lot more canoes, kayaks, snorkelling and diving. A lot more people want commercial operations. The name has definitely got out.”

Even surfers have begun making pilgrimages to Ningaloo’s increasingly famous reef breaks, including Lighthouse Bay and Tantabiddi, at the northern reach of the marine park, and Red Bluff and Gnaraloo – which is also a mecca for international wind and kite surfers – in the south.

Scientists are also beginning to tease out some of Ningaloo’s more subtle secrets. In autumn this year, researchers from the Australian Institute of Marine Science discovered in the marine park’s deeper waters gardens of sponges that are thought to be species completely new to science.

Search for whale sharks

Rob Connaughton, a lanky young pilot with a mop of black curly hair, is based at one of the most low-key airport terminals in the country. When he’s not flying, he spends his days waiting for tourists in an ancient white caravan that sits in the middle of a gravel-and-spinifex field 1km from Yardie Homestead on the northern tip of North West Cape. Part of Rob’s job is to help skippers and scientists locate whale sharks. While the world’s biggest fish can reach lengths of 12m, they glide a few metres below the surface and rarely breech, making them almost impossible to see until a boat is virtually on top of them.

Offshore, out of sight on the seaward side of Ningaloo Reef, a cruiser loaded with tourists – more than half of them aged 21–35 years and heralding from Australia, Europe, Japan and the UK – is waiting for Rob to take off and pinpoint the sharks and manta rays.

Leaving behind a plume of dust, we’re soon flying over the sand dunes fronting Ningaloo lagoon and then heading out to sea. It’s a magnificent day – light winds, unbroken blue skies and an ocean so clear the shadow of a boat is cast sharply on the seabed.

At first glance it’s hard to believe there’s any life at Ningaloo. There are no trees on the shoreline, no fresh water, only the great Indian Ocean meeting the extreme edge of a baked continent. To the south, the reef stretches away to the horizon.

It’s the Leeuwin Current that’s the giver of life in these waters, maintaining a rich flow of warm water and a conveyor belt of nutrients along the WA coast.

While whale sharks may be the first things someone thinks of when they hear mention of Ningaloo, the entire ocean is teeming with life. Every few seconds the sea below our aeroplane boils over in football field-sized patches as schools of fish break the surface and flocks of seabirds sweep down to join the feast.

As we approach the boat, the skipper’s voice crackles over the radio. He sounds euphoric. “Rob, it’s fantastic down here! The reef went off this morning. We had a good dive with a 6m shark, there were mantas jumping and the visibility was superb.”

We fly in expanding circles around the boat. A black smudge, resembling a half-submerged car, comes into view. “There’s a manta out here if you want it,” Rob says to the skipper.

“Yep, which way?”

“A kilometre. Your one o’clock.”

The boat speeds towards the pirouetting manta, Rob guiding it in. “Your 11 o’clock, 20 boat lengths,” he says.

The boat slows. “Okay, thanks mate. I can see it now.”

From 500m we watch a rush of people splash into the water and swim towards the manta.

Rob heads south, his neck cricked searching for the creature that sits at the summit of the WA ecotourism food chain. The local boats guarantee visitors an encounter with the world’s biggest fish, which is why so much effort goes into working out exactly where they are. If a whale shark isn’t found, the operators promise to keep taking out visitors until one turns up.

The pressure’s on Rob too; spotting whale sharks can be difficult. “They almost look like a tadpole,” he says. “Their tails are negatively buoyant so they sink down and they have this big flat head. If you see a small one you have to make sure it’s spotted not stripy because you do get tiger sharks hanging around here as well.” More than once a boatload of snorkellers has been offloaded onto a man-eater instead of a whale shark. “It happens occasionally, but I haven’t done it yet,” Rob says.

We’re now running parallel to the reef, waves crashing in tubes that seem to last half a minute. A smudge appears in the water. It does look like a tadpole but, because of its pectoral fins, a partly metamorphosed one. Its motion is slow and calm. Rob calls the skipper. “I’ve got a whale shark here. It’s about 6 m, heading up along the reef towards the north passage.”

The boat speeds towards the enormous fish while we fly tight circles directing the skipper until he’s 30m – the legally designated minimum distance – in front of the shark. The tourists jump into the ocean and split into two groups – one on each side of the behemoth. After a few minutes, only the strongest swimmers maintain their shark-side vigil and then it dives, disappearing from view.

Camping on the dunes – privates beaches

The reef at Ningaloo is rarely more than a few kilometres offshore and in many places it’s directly off the beach – even children can wade out to it. This proximity to the mainland means that anyone with legs, flippers, a boat or even a kayak can experience the marine park’s best corals.

Getting around the park, however, is more difficult. Because the region is so remote and tourist infrastructure little developed, many roads are rugged and poor, and require difficult four-wheel driving. To overcome this, Andrew and I brought an inflatable zodiac, which allowed us to escape from both of the coast’s two tourist centres, Exmouth in the north and Coral Bay 140km to the south. We camped halfway between the two amid the sand dunes of Lefroy Bay. Out on the water here, in the middle of the day and in the space of just half an hour, we saw dozens of green turtle heads popping up on all sides of our boat, dolphins porpoising between coral stacks, and a dugong and her calf – two of a 1000-strong local population – grazing on seagrass.

Lefroy Bay fronts land owned by Ningaloo Station, a 5056sq.km pastoral lease used for sheep since the late 1800s. Here, visitors can stay as long as they like, camping in the dunes and paying a few dollars a day to an infrequently seen manager. According to Dec figures, the average length of stay for visitors to places such as Lefroy is an amazing 47 days – testament to both how hard it is to gain access to these remote campsites and how good it is once set up.

Silver-haired semi-nomads hunker down for months. They erect enormous poles to fly the Australian flag and, at night, fend off the immense darkness of the desert wilderness with generator-powered lights.

Some, like the Peaks and Sellicks, lifelong friends from Mandurah, 65km south of Perth, are here for a few weeks of fishing and beer-drinking. For them, Ningaloo is the working man’s Great Barrier Reef. Sitting on her camp chair just metres from the turquoise water, and wearing a sleeveless shirt despite the still-baking dusk sun, Bernice Sellick sums up the attraction of Lefroy. “Where can you camp and have water like that?” she says, pointing to a beach she shares with only her friends and husband.

Don’t count on a cocktail or a glass-bottom boat at Lefroy Bay any time soon. But things are changing – the days of simply parking a van anywhere in the dunes are coming to an end. Justifiably concerned about the environmental damage caused by unregulated camping and rapidly increasing visitor volume, the WA Government plans to take control of this ocean frontage once the station’s pastoral lease expires in 2015. As with an increasing section of the Ningaloo coast, that means set campsites and the end of an era that has seen generations of WA families load their cars to the gunwales and head off to Ningaloo sans rules.

A few kilometres south of Bernice’s camp, half a dozen big caravans, tables and chairs are set up under tarpaulins on top of a dune. It’s the perfect spot to watch the most exciting show in town – sunset. On our first night at Lefroy, we had stared at a sunset that seemed more like a slow-motion atmospheric nuclear test than dusk. While everyone has a boat, these long-term fishos and campers are oblivious to how good the snorkelling is. They’re genuinely surprised when we recount the underwater spectacles we’ve seen.

Treading water several kilometres offshore, I note how harsh and desolate the mainland looks. But taking a breath and ducking beneath the chop, I see why Ningaloo’s a candidate for World Heritage listing. Every dive is different – unique bommies, corals, sea life and underwater topography.

In half a dozen locations at Lefroy we set anchor and jump in. Reef sharks circle on the edge of our vision and painted crayfish as long as a man’s arm haunt the reef’s caves and ledges. Amazingly, although it’s the peak of the season, no one else is in the water. In fact, there’s every chance that in the entire middle third of Ningaloo Marine Park – the stretch between Yardie Creek and Coral Bay – Andrew, the dugongs, dolphins and I are the only mammals in the lagoon.

In contrast to the Great Barrier Reef, we see no great colourful fans of coral but what is astonishing is the mega diversity crammed into the roughly 300km of coastline along which Ningaloo Reef runs parallel. It’s easy to believe that there’s enough life before my goggles to fill volumes of textbooks. Officially, there are more than 200 coral, 600 mollusc and 500 fish species.

World heritage listing for Ningaloo

In 2004, Coral Bay shot to national fame when conservationists, led by WA novelist Tim Winton, mounted a campaign to stop a marina resort and residential development being built at nearby Mauds Landing. The resort was rejected by the State Government, which followed up its decision to control big developments with an announcement that World Heritage listing for Ningaloo would be pursued. This is now underway. Until little more than a decade ago, Coral Bay was a sleepy camping ground, a dot between two vast stretches of wilderness coast.

It was a place people brought their families, tinnies and canvas tents. It was the kind of spot where any dad, no matter what his job back home in Perth, could say: “Kids, I wonder what the poor people are doing tonight?”

Everyone agrees that things are changing – the boats are getting bigger, whiter and shinier. The caravans are now the size of small houses and there are more people every year – more pressure on Ningaloo’s animals big and small to perform for the crowds.

There’s a proposal to tear down the pub at Coral Bay and replace it with a five-star hotel, while the remaining two freehold landowners at Coral Bay are looking at resort-style developments and these are likely to go ahead in some form. Further north, Exmouth is experiencing a boom, with a major marina and canal-style housing development currently under construction.

While the whale sharks might be holding their own against the rising tide of people, some are worried about creatures such as the manta ray. This includes Murdoch University manta ray researcher Frazer McGregor, who’s so passionate about the winged fish he also works as a tour-boat deckhand along the coast.

“Until now, Ningaloo has been saved by its isolation and protected by its inhospitable environment,” he says as we shoot across the water in search of dancing mantas. “But how much disturbance can they bear?”

Source: Australian Geographic Oct- Dec 2006